Why Isn’t Automation Creating Unemployment?

Research Summary 2017-1

New artificial intelligence and robotic technologies are fueling fears that automation will cause widespread unemployment. Yet unemployment in the US is at its lowest level in 16 years. Some economists see this as evidence that recent technological change is not so great after all (Gordon). But there is another explanation that is supported by growing evidence: while automation today is associated with job losses in manufacturing, it is associated with overall job growth in other sectors.

A new research paper, “Automation and Jobs: When technology boosts employment,” by James Bessen, explores why automation often boosts employment in affected industries and presents evidence about where this is happening today. The analysis suggests that major new advances in technology, while possibly disruptive, are not on course to create major unemployment overall in the near future.

How automation boosts employment

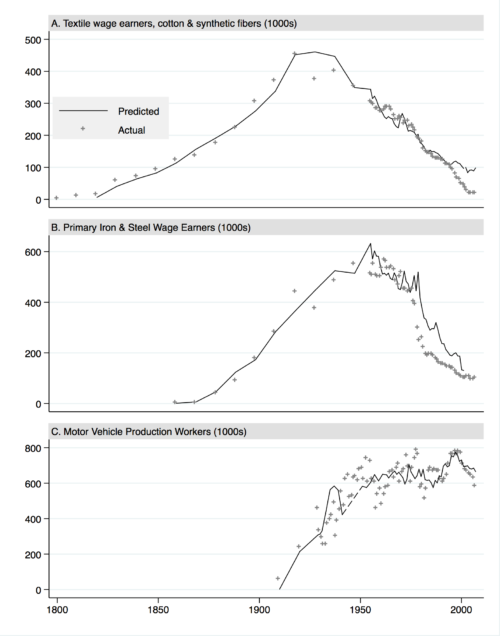

Many people assume that industries necessarily shed jobs when they are automated. But that view is wrong. The decline in manufacturing employment since 1950 provides strong evidence that automation sometimes eliminates jobs (globalization also played a part, especially recently), but that wasn’t always true. Prior to the 1950s, employment grew in many manufacturing industries despite strong productivity growth (see figure).

What changed? Why is automation sometimes a powerful engine of job growth and not at other times? And what does that tell us about today’s technologies?

The paper starts by providing a simple explanation that accurately explains the rise and fall of employment in the textile, steel, and automotive industries. The critical factor is the changing nature of demand. Automation doesn’t just reduce the amount of labor needed to produce, say, a yard of cloth. In a competitive economy, it also reduces the price of that cloth or improves its quality. And those changes increase demand for cloth. If demand goes up enough, employment in the textile industry will grow even though less labor is needed per yard of cloth.

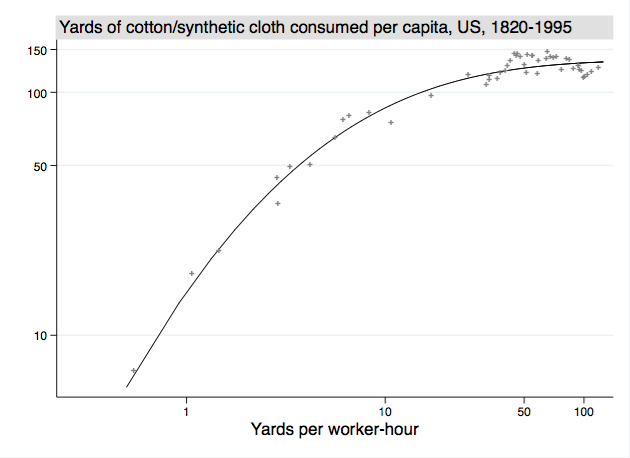

This is exactly what happened. The figure below shows the huge growth in per capita consumption over time as productivity grew and prices fell. Because demand grew more than productivity before 1950, employment grew. But the figure also shows that the rate of growth of demand slowed over time. After 1950, demand has grown more slowly than output per worker, leading to declining employment.

Changing demand

A key insight of the paper is that this shift in the nature of demand is common across a broad class of consumer preferences. When goods are so costly that there are large unmet needs, consumer demand is highly responsive to technological improvements that lower cost or improve quality (economists call this elastic demand). But when goods become highly affordable, further technological improvements only have a small effect on demand (inelastic demand). Demand gradually becomes satiated as consumers are able to afford more and more uses for the product.

For example, during the early 1800s, cloth required a very large amount of labor to produce, making it very expensive. The typical person could only afford one set of clothing. Because there was such large unmet need, a drop in price induced a large increase in cloth purchases. But by the mid-twentieth century, people had closets full of clothes, upholstered furniture, draperies, etc. Because most needs were already met, a further drop in the price of cloth just didn’t increase demand very much. This changing responsiveness explains why textile automation was accompanied by a century of job growth before reversing.

In the paper, a simple model based on this intuition accurately predicts the rise and fall of employment in the textile, steel, and automobile industries—the solid lines in the figures above are derived from this model, taking into account the effects of population growth and trade. The fit is quite good apart from job losses in recent decades associated with global trade, supporting the view that demand is key to understanding whether automation increases or decreases employment in the affected industries.

Today?

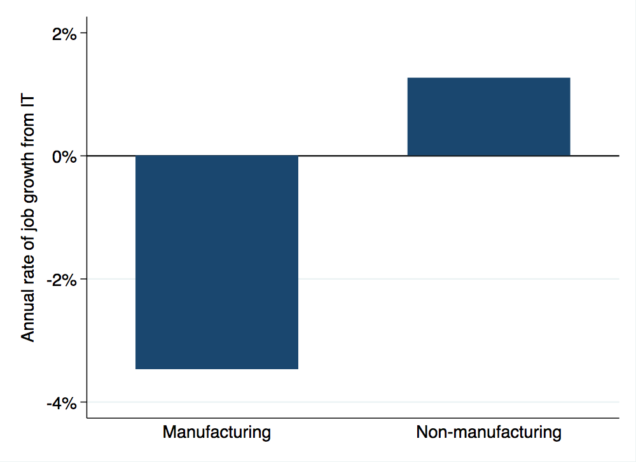

But what is the effect of automation based on new information technologies today? The analysis suggests that automation in many manufacturing industries will lead to further job losses because markets are saturated, but to the extent that IT-based automation affects non-manufacturing industries, automation may boost employment, at least somewhat, in these industries.

The paper shows evidence that this appears to be the case and this finding is supported by some recent research. Gaggl and Wright (2017) find that IT tended to raise employment in wholesale, retail, and finance industries, but had no statistically significant effect on other sectors, including manufacturing. Mann and Puttman (2017) also find that automation, measured using patents, led to job declines in manufacturing, but job growth in the service sector. Akerman, Gaarder, and Mogstad (2015) find that Internet technology increased employment of skilled workers and had no effect on the unskilled. Bessen (2016) finds that computer automation is associated with increases occupational employment modestly overall, with job losses in low wage occupations. Gregory, Salomons, and Zierahn (2016) find that automation of routine tasks tends to eliminate certain jobs, but that net employment increases. Autor and Salomons (2017) find that productivity growth leads to net increases in employment, although not in the directly affected industry. Studies of the effect of robots—largely utilized in manufacturing—have either a negative or neutral effect on employment (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2017, Graetz and Michaels 2016).

Overall, this evidence tends to support the view that automation today appears to be increasing employment outside the manufacturing sector. The news is not all good, however. While net employment may increase in automated industries, often jobs in certain occupations are eliminated. Moreover, in order to fill the newly created jobs in other occupations, workers often need training or they may need to relocate. Hence automation is still highly disruptive even if it does not cause mass unemployment.

Some people argue that current technologies are more likely to cause unemployment because the pace of change is faster. But that ignores the role of demand: if demand is sufficiently elastic, faster technological change will lead to faster job growth. Furthermore, the positive impact of IT automation is not likely to disappear in the near future because it depends on consumer demand and the nature of demand only changes slowly.

In the more distant future, the story might be quite different and service sector jobs might experience the kind of declines we now see in manufacturing. However, this analysis suggests that as long as new technology is addressing major unmet wants, it need not create mass unemployment. However, the challenge for policymakers is to help people acquire the skills needed to work with new technologies.

Acemoglu, Daron and Pascual Restrepo. 2017. “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from U.S. Labor Markets.” NBER Working Paper.

Akerman, Anders, Ingvil Gaarder, and Magne Mogstad. 2015. “The Skill Complementarity of Broadband Internet.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(4): 1781–1824.

Autor, David and Anna Salomons. 2017. “Does Productivity Growth Threaten Employment?” Working paper.

Gaggl, Paul, and Greg C. Wright. 2017. “A Short-Run View of What Computers Do: Evidence from a UK Tax Incentive.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 9, No. 3, July 2017, pp. 262-94.

Gordon, Robert J. 2016. The Rise and Fall of American Growth. Princeton University Press.

Graetz, Georg, and Guy Michaels. 2015. “Robots at work.” CEP Discussion No. 1335.

Gregory, Terry, Anna Salomons, and Ulrich Zierahn. 2016. “Racing With or Against the Machine? Evidence from Europe.” Utrecht School of Economics, Tjalling C. Koopmans Research Institute, Discussion Paper Series 16-05, July.

Mann, Katja and Lukas Püttmann. 2017. “Benign Effects of Automation: New Evidence from Patent Texts” Working Paper.