Tao He

The Role of Terror in Late Imperial Russia

Introduction

Revolutionary Russia is an ambiguous term because opinions differ as to when the “revolution” really began. History textbooks and encyclopedias focus mainly on the 1905 Revolution, the February Revolution, and the October Revolution. However, these dates are only the pinnacle of a series of social unrest, radicalization and terror that arguably began as early as the assassination of Tzar Alexander II in 1881. Thus in order to gain a more comprehensive perspective on the Russian Revolution, one must examine the this trend of radicalization and violence towards the fall of Imperial Russia.

The rise of new political factions spearheaded the wave of terror that plagued the late imperial period. Many factors lead to the success of these groups. The outcry for political and social reform within the intelligentsia intensified with developments in the west. Furthermore the failure of the Russo-Japanese war made Russia, as a western imperialist power, reevaluate its place in the global arena. However political complaints on the grass root level was ineffective in an autocratic government structure. Although figures such as Sergei Witte and Pyotr Stolypin attempted to save empire through progressive social and economic reforms, the circumstances at the time worked in favor of the revolutionaries.

Terrorism was one of the revolutionaries’ quintessential tools to push for revolution. It was used for ideological and practical purposes. On the one hand, the physical destruction of imperial property was ideologically sound because it implied a subsequent creation of something better. On the other, many of the terrorist groups were underfunded and used ideological violence as an excuse for personal or group benefit. Terrorism in the late imperial period was significant to the Russian Revolution because it was one of the defining qualities of Russian Socialism.

Points of Research

Historical Context/ Definitions

- How to define the time frame of “Revolutionary Russia”

- What exactly constitutes terrorism?

Politics

- What prompted the various socialist factions to use terrorist methods?

- Was terrorism really necessary for the political aims of these parties?

Social forces

- How was terrorism different between rural and industrialized parts of the empire?

- What were some of the social forces that radicalized the Russian intelligentsia?

Psychology

- What were the mindset and personal motives of active terrorists and double agents?

- Ideology vs Practicality, How was each important for socialist political factions? Was one more significant than the other?

Encyclopedias and Textbooks

Merriman, John M. A History of Modern Europe: From Renaissance to the present. W.W Norton. New York. 2010

-This is a standard textbook for a basic understanding of modern Europe. One chapter is dedicated to the Russian Revolution. Although this book only provides a very broad and general overview of the revolutionary Russia, it is a good starting point. The bibliography at the end of this book and the additional reading sections serve as valuable tools to begin my research on revolutionary Russia.

Cherniaev, V. Iu. Rosenburg, William G. Critical Companion to the Russian Revolution, 1914-1921. Indiana University Press. Bloomington. 1997.

- The Critical Companion is an encyclopedia that encompasses a variety of topics on the Russian Revolution. This is not only a good resource for historical background and context but also opens the door to various primary and secondary sources. The Companion article a concrete understanding of seemingly broad or vague concepts such as the aims and platforms of various political factions in the Constituent Assembly. This also allows me to search for the role of terrorism in each of the subtopics.

Gerasimov, Ilya V. Modernism and public reform in late Imperial Russia: rural professionals and self-organization, Palgrave Macmillan.Basingstoke. 2009

- This book explains the social, cultural and political landscape in late Imperial Russia. The book begins at 1905 and give a detailed overview of Russia between then and 1917. It focuses on the social dynamic in both peasant agrarian towns and in the cities. Most importantly, he explains the process of radicalization in the youths of Russia at this time and how anti-state movements gained social support.

Scholarly Books and Journals

Geifman, Anna. Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1995

Thou Shalt Kill does a good job explaining both the political and cultural motives behind terrorism from the late imperial period to the after the October Revolution. The book is structured in a way that analyses the role of terrorism in each political faction (Social Democrats, Social Revolutionaries, Kadets, etc.). Specifically, Prof. Geifman focuses on how each faction resorted to terror to fight the imperial government. She also documented the historically significant acts of terrorism such as the assassination of Stylopin.

- Social Revolutionaries– Agrarian communists faction founded in 1902. The SR party was founded on the ideology of the Russian Populist movement. Terrorism could be considered an integral part of this party. Supporters of this faction mainly comes form the relatively rural caucus regions. The SR often align with various local bandits and anarchists. The terrorism conducted by the SR included attacks on police officers, assassinations of public figures, destruction of government buildings and monuments. Due to the largely unorganized nature of the attacks, it was ambiguous to whether the majority of the terrorist activity was actually approved by SR party officials.

Grigory Gershuni was the Socialist Revolutionary who founded the terrorist branch, Combat Organization. He was arrested as a result of the Azef Affair.

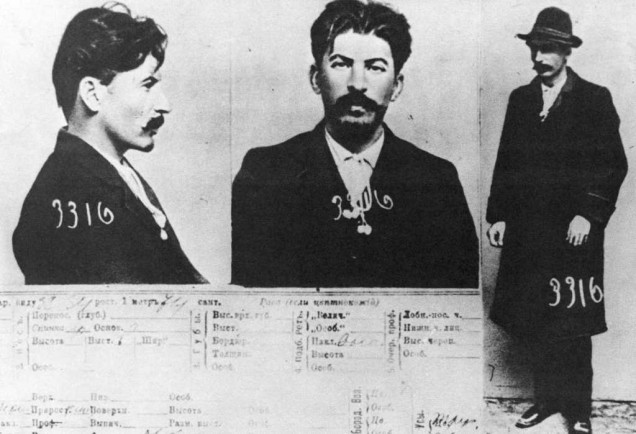

- Social Democrats– This group was the original Proletarian Communist Party which later separated into the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks. Founded in 1883 this political faction was mainly based in the more urban areas and populous cities such as St. Petersburg and Moscow. In comparison to the Social Revolutionaries, the SD was much more organized. They wanted a communist revolution from the proletariat. In terms of terror, the SD were much more discrete and organized than their agrarian counterparts. Although the party agreed that terrorism was necessary to bring down the Tsarist regime, opinions differ on the scope of terrorism. The Bolsheviks believe that terror and violence were crucial in pushing for revolution, whereas the Mensheviks believed in a slower paced revolution and minimal terror.

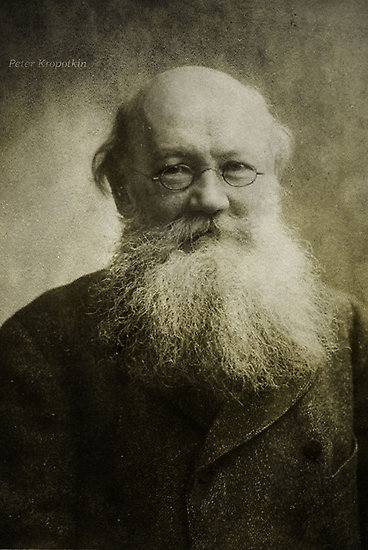

- Anarchists- The most radical and disorganized group. The political aims of the Anarchists were “to demolish the contemporary order” and essentially create a stateless society through violent social revolution. Many Anarchist factions were composed of overly radical members from the SR and SD. Though the ideology behind Anarchism differs from place to place, one prominent theory comes from the writings of Petr Kropotkin, who believed in mass violence against a the government rather than individual terrorist acts. However the extent and frequency of violence from the anarchist exceeds that of the SD and SR, partly because it was difficult to distinguish Anarchist political terrorism and regular crime committed my a party member. Anarchists often used political terror as an excuse to rob civilian homes and destroy property.

Weeks, Theodore R. Nation and State in Late Imperial Russia: Nationalism and Russification of the Western frontier, 1863-1914. Northern Illinois University Press. DeKalb. 2008

- Although this book is not about terrorism, it nevertheless explains the political and cultural background of Late Imperial Russia. The author focuses on the conflicts between the multi-ethnic groups and nationalism. The interactions between Slavs, Poles, Jews, Russians and various other minorities brings to light some of the causes for the rise terrorist violence in the years following.This book also analyzes the idea of “National Mentality” of the Russian Empire. I will compare the Week’s insights regarding the national and ethnic problems Imperial Russia with Geifman’s points on how various political groups viewed Terrorism as a necessity. This comparison will provide a more comprehensive understanding on the why terrorism was so widespread in late imperial Russia.

Geifman, Anna. Entangled in Terror: The Azef affair and the Russian Revolution. Scholarly Resources. Wilmington. 2000

- This is one of the few sources that focuses on the psychological aspects of terrorism. Evno Azef was a double agent who worked as a spy for the Tzarist imperialist police and as an active member of the Combat Organization (A branch of the Socialist Revolutionaries in charge of carrying out acts of terrorism and assassinations.) Through manipulation Azef was able to get Gershuni, the leader of the Combat Organization, arrested and obtain the position for himself. At the same time he also carried out a multitude of significant assassinations including that of the Grand duke Sergius Alexandrovitch. According to popular historiography Asef was remembered as a provocateur but Geifman argues otherwise. This book focuses on the psychological aspects of the Azef affair. The author ultimately concludes that it was both Azef’s complicated personal life and the chaotic political background that caused him to do what he did. This goes to show that logic and rationality does not always dictate human actions. The nature/nurture paradox, in this case, applies to explain some of the intricacies of terrorism in this period.

Yevno Azef was a double agent who worked as a member of the Tzarist police and leader of the SR terrorist branch.

Geifman, Anna. Death Orders: The vanguard of modern terrorism in revolutionary Russia. Praeger Security International. Westport. 2010.

- This book is specifically about terrorism in revolutionary. What makes this source special is that it focuses more on the perspective of the terrorists as opposed to how terrorism plays into greater political scheme. It also analyses the trends in organized violence and how it gradually shifts from targeting high profile targets such as members of the Tzarist monarchy to simply senseless murder of civilians. Geifman attributes this moral degradation to “historical dislocation.” Taking a psychological approach, she explains that the disintegration of traditional values and rise of anarchism, and death culture, created the perfect conditions for a revolution rooted in terrorism. She also makes the argument that revolutionary Russia was the origin of modern terrorism.

Hutchinson, John F. Late Imperial Russia, 1890-1917.Longman. London; New York. 1999

- This book covers the last days of Imperial Russia. It analyzes the various reasons for its collapse including problems in social structures, terrorism, radicalization, the 1905 revolution, and finally, the First World War. It also analyzes Tzar Nicholas as a leader and as a person. This source is useful because the scope is large enough to provide the bigger picture on how each factor falls into the historiography but just narrow enough to stay in the boarders of the Late Imperialist period.

Mayer, Arno J. The Furies: Violence and Terror in the French and Russian Revolution.Princeton University Press. Princeton. 2000.

- This source focuses on the connection between social ideologies and terror. Mayer compares the role of capitalism in the French Revolution to the role of Marxist ideology in it’s Russian counterpart. He explores the subject of organized violence in both cases and how it developed. Mayer juxtaposes the exportation of the revolutionized France, in the form the Napoleonic conquests, with Russia’s internal terrorism.

Verhoeven, Claudia. The odd man Karakozov: Imperial Russia, modernity, and the birth of terrorism. Cornell University Press.Ithaca. 2009

- This source analyzes the development of terrorism and anti-state violence in late imperial Russia. Verhoeven focuses on Karakozov’s attack on Tzar Alexander II as the spark that catalyzed terrorism for later Revolutionary groups. This book touches on both political and psychological factors that began modern terrorism. She argues that, in an autocratic state, the people are politically helpless by nature. Thus, thus terrorism became one of the only means of making change. She also juxtaposes the development of violence to the developments of ideology, science and public political participation. This source serves as both a case study on the assassination of Alexander II and a analysis of how modern terrorism in Russia came to be.

Naimark, Norman M. Terrorists and social democrats: the Russian revolutionary movement under Alexander III. Harvard University Press. Cambridge. 1983

- This book address the issue of political violence from a narrower scope than the previous scholarly sources. First this book only focuses on the Social Democrats, which includes the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks. Second it specifically deals with the wave of terrorism prior to the First World War. Naimark considers the assassination of Alexander II as the spark that started modern terrorism in Russia. The conservative backlash adopted by his success Alexander III only further radicalized the estranged Russian society. This source not only explains the motives of the SD’s in carrying out seemingly anarchic acts of violence but also describes many of the Tzarist countermeasures. For instance, Pyotr Stolypin social reforms in improving the peasant class gave many of the radicals exactly what they wanted. However Stolypin was nevertheless assassinated. In short the author is arguing that the social unrest and hatred for the autocracy was beyond repair. The wave of terrorism between the assassination of Alexander II and World War I was a calculated strategy to create social chaos before starting the revolution.

Pyoty Stopypin was the prime minister, known for his progressive social reforms and suppression of terrorism. He was assassinated in Kiev in 1911

Geifman, Anna. Russia under the Last Tsar: opposition and subversion, 1894-1917. Blackwell Publishers. Malden. 1999

- This book deals exclusively with the regime of the last Tzar, Nicholas II with an attention to terrorism. Moreover it covers many of the factors that contributed to the end of autocratic rule in Russia. Geifman analyzes the end of imperial Russia from both political and psychological perspectives. In terms of politics, Russia was in a troublesome state. The failure and humiliation of the Russo-Japanese, the various problems of World War I and the internal outcry for reform and revolution all accumulated onto the weak imperial government. On a personal and psychological level, the prince’s hemophilia and Nicholas’ indecisive and reactionary personality only contributed to the collapse of the autocracy.

Pipes, Richard, Degaev, Sergei. The Degaev affair: terror and treason in Tsarist Russia. Yale University Press. New Haven. 2003

- Sergei Degaev, like Azef, was a double agent who worked for the Russian police and an active member of Narodnaya. This book serves as both a primary and secondary source because Degaev contributed to it after he fled to the United States. This source is useful because it could be compared and contrasted with the Azef affair. Although the stories seem parallel, the psychology and social background in the two cases ultimately provide very different understandings of terrorist mentality.

Leon Trotsky. Dictatorship Vs. Democracy (Terrorism and Communism)

This is both a primary and secondary source. Although it was written by Trotsky, it was written as a response to Karl Kautsky, a prominent critic of the Soviet State who believes that the Bolsheviks’ tactics in assuming control was in accordance with true Marxist ideology. This book is Trotsky’s defense of terrorism during the revolution. It explains why terrorism was necessary in the context of the Russian Revolution. It also aims to legitimize the actions of the Bolsheviks with Marxism.

Primary Sources

Sergei Nechayev. The Revolutionary Catechism. 1869

- This was one of the earliest sources that explicitly explains some of the duties and obligations of the terrorist revolutionary. The Revolutionary Catechism was highly influential for the both the Combat Organization in the SR and the SD. This source was essential a basic guide for how to be a terrorist in revolutionary Russia.

- “The revolutionary is a doomed man. He has no personal interests, no business affairs, no emotions, no attachments, no property, and no name. Everything in him is wholly absorbed in the single thought and the single passion for revolution.”

- “Tyrannical toward himself, he must be tyrannical toward others. All the gentle and enervating sentiments of kinship, love, friendship, gratitude, and even honor, must be suppressed in him and give place to the cold and single-minded passion for revolution. For him, there exists only one pleasure, on consolation, one reward, one satisfaction – the success of the revolution. Night and day he must have but one thought, one aim – merciless destruction. Striving cold-bloodedly and indefatigably toward this end, he must be prepared to destroy himself and to destroy with his own hands everything that stands in the path of the revolution”

- “This filthy social order can be split up into several categories. The first category comprises those who must be condemned to death without delay. Comrades should compile a list of those to be condemned according to the relative gravity of their crimes; and the executions should be carried out according to the prepared order.”

- “When a list of those who are condemned is made, and the order of execution is prepared, no private sense of outrage should be considered, nor is it necessary to pay attention to the hatred provoked by these people among the comrades or the people. Hatred and the sense of outrage may even be useful insofar as they incite the masses to revolt. It is necessary to be guided only by the relative usefulness of these executions for the sake of revolution. Above all, those who are especially inimical to the revolutionary organization must be destroyed; their violent and sudden deaths will produce the utmost panic in the government, depriving it of its will to action by removing the cleverest and most energetic supporters.”

- “By a revolution, the Society does not mean an orderly revolt according to the classic western model – a revolt which always stops short of attacking the rights of property and the traditional social systems of so-called civilization and morality. Until now, such a revolution has always limited itself to the overthrow of one political form in order to replace it by another, thereby attempting to bring about a so-called revolutionary state. The only form of revolution beneficial to the people is one which destroys the entire State to the roots and exterminated all the state traditions, institutions, and classes in Russia.”

- “To weld the people into one single unconquerable and all-destructive force – this is our aim, our conspiracy, and our task.”

Petr Kropotkin. Fields, Factories and Workshops. 1898

- Kropotkin was a learned activist who wrote on creating a truly anarchistic system. Fields, Factories and Workshops was about communism and self efficiency in small localized communities. He argues that government was ultimately unnecessary if every community can produce everything it demands. Although this book was considered one of the benchmark anarchist literature, it included no mention of terror. It is interesting to see how the various violent Anarchist groups in revolutionary Russia have distorted the original vision of a collaborative, control free, system.

Boris Yelensky. Memoirs. 1906

- Boris Yelensky was a member of the Socialist Revolutionary. This memoir describes the events from beginning from his involvement with the SR to the 1905 revolution. Yelensky account provides an inside look on how the SR (one of the most violent political groups) view the Imperial Russia and rival political parties.

Mikhail Bakunin. Statism and Anarchy. 1873

- Bakunin was an anarchist who believed in Collectivist Anarchism, a system where there is no government and the producers have control. In Statism and Anarchy he first points out the flaws of Socialism, namely the impossibility for the proletariat to rule effectively. He understood that the proletariat would be too large as a ruling body and must have a representative body. However by creating such a body, the notion of parliament and elitism will began to once again bring class distinctions to society. His alternative was to create a system that will bring “an end to all masters and to domination of every kind, and the free construction of popular life in accordance with popular needs, not from above downward, as in the state, but from below upward, by the people themselves, dispensing with all governments and parliaments – a voluntary alliance of agricultural and factory worker associations, communes, provinces, and nations.“

John Reed, Ten Days that Shook the World, 1919

- John Reed was an American journalist covering the story of the October Revolution. This book offers an eye witness primary account of political violence from an outsider’s point of view. The second chapter, The Coming Storm explains the events of the Bolshevik take over.

Babel, Issac. Red Cavalry W.W. Norton & Company. New York. 2002.

- Red Calvary was not only a representative piece of literature from the early soviet era but also a collection of symbolic parables that illustrates some of the problems of the Soviet Union in its infancy.The power of these accounts lies in Babel’s ability to depict some of the underlying social and moral problems of Russia, through distortions of human nature in seemingly mundane incidents. From the travels of the narrator, Babel explored wartime corruptions in moral identity as well as the abuses of Jews and soviets during the Polish-Soviet War. The constant brutality depicted in this historical fiction reflects the psychological realities of Revolutionary Russia.

Riha, Thomas. Readings in Russian Civilization. University of Chicago Press. Chicago.1969.

The Readings in Russian Civilization is a collection of historically significant primary sources with scholarly introductions and annotations. Through these sources, it paints an image of Russia from as early as the medieval period to 1963. Here are a few of the documents in which I found useful for studying terrorism and political violence in revolutionary Russia.

- #31 Killing An Emperor by David Footman:This entry consists of a series of quotations from the trials of the members of the People’s Will who were responsible for the assassination of Alexander II. This sours is significant no two levels. First it gives the us a first hand account of how trials of terrorism were dealt with in late imperial Russia. Second, it allows us to analyze the psychology of the revolutionaries who murdered a progressive and liberal Tzar.

- #41 A Need For Great Russia by Pyotr Stolypin: Stolypin was one of the prominent statesmen in late imperial Russia. He was first appointed minister of interior then prime minister by Nicholas II. He advocated various ambitious agricultural and social reforms in attempt to prevent the revolution. Although he was politically conservative, many of his policies were progressive. He was also very effective in subduing the wave of terrorism between 1903 and 1905. This source provides some first hand insight on his view of what the social identity of Russia ought to be. He stresses nationalism and unity of imperial citizens. His ideology directly clashes with the platforms of the rising revolutionary factions such as the SD and the SR. How this his ideal realistic/unrealistic in the historical context? Was he really a threat to revolutionary aims?