Nicholas Richardson

Political Violence and Stalin’s Vision of Socialism 1918-1938

The goal of this research guide will be to provide a resource for the study of political violence in Revolutionary Russia under Joseph Stalin, specifically between the years of 1918 and 1938. Political violence, for the purposes of this guide, involves the use of coercion and manipulation to create the ideal image of a Socialist Soviet state. It also pertains to the numerous policies designed to root out and destroy any possible opposition. The emphasis of this research will not necessarily be on the day to day lives of those affected by Stalinist policies of political violence, all though that will be addressed. Instead, the focus will be on the ideology of Stalinist violence and of Stalin himself regarding his vision of a post-Revolution Socialist nation.

The legacy of political violence and terror in Russian history is as old as Russia itself, but the instances of terror in the interwar years were unprecedented due in large part to the cataclysmic events that had occurred in the years prior, including the Great War, the Civil War and of course the Revolution itself. As much a part of Russian culture as anything else, it is argued that violence as policy was rooted in the origins of the Red Terror, and eventually shaped it up through the Great Purges. The main organs of the application of terror as policy included the secret police, which went through many iterations during the interwar period, including the Cheka, GPU and NKVd. Other prevalent instances of political repression involved mass arrests and the use of show trials. As Stalin’s regime evolved, so too did the ideology of these policies; by the end of the Great Purges, innocence was a relative term, as soon nearly everyone was seen as an enemy in some way, shape or form.

Ideology will serve as the crux of a majority of the investigation of this research. As time passed, the ideology of Stalin became the ideology of the regime. This, however, brings up another issue entirely, that being whether or not Stalin truly held true to a certain set of beliefs. Some argue that Stalin was the heir apparent to Lenin and carried on his ideals, albeit with a significant increase in the use of repressive tactics. Others insist that Stalin’s ideology was a complete betrayal of the fundamental beliefs of Marx and even Lenin. And then there are those who say that Stalin adhered to no ideology whatsoever, that he was simply a cold, cynical and power-hungry dictator who made his word law. The rationality and justifications given or imagined for the Stalinist reign of terror will be examined in detail, including whether or not an ideology can justify the suffering of millions of people, and if there were any benefits to the use of political violence in Revolutionary Russia.

General Sources

– Conquest, Robert, The Great Terror: A Reassessment, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

One of the definitive texts on the Great Terror, Conquest’s book is a reassessment of his original work published in 1968 based on newly discovered information regarding the time period he investigated. While Conquest goes into great detail in regards to many aspects of the Great Terror, but for the purposes of this research paper, the focus will be on Conquest’s thoughts on both the origins of the Terror and of the nature of its goals as put forward by Stalin and others. Conquest sees the terror as a product of the numerous complexities of the Bolshevik system. He also believes that Stalin’s desires did not come from a place of fanaticism like Hitler; instead, he saw Stalin as very cynical and business-like in his view of the world. He often positioned himself as a moderate and let others be radical in his place. Because of this, Conquest asserts that Stalin was eventually able to surround himself with men who were wholly dependent on him for power and security.

– Stephane Courtois et al., The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999).

This collection of writings by the authors mentioned focuses on the various examples of Communism throughout the 20th century, with Courtois being the main investigator of Russian Communism. Courtois looks at the policies enacted by the regime in the post-October years, especially those enforced by the Cheka. He looks at how the Cheka’s actions were often dictated by the fanatical need for efficiency by the regime; the Cheka had to fulfill a certain quota of arrests regardless of the innocence of their targets. The regime’s need for total control and obsession to root out potential saboteurs is evident in Courtois’ writing. Examples of this include the Shakhty trial of 1928 and the assassination of Sergei Kirov in 1934; in Courtois’ eyes these were turning points in the history of the Terror. Courtois also examines the ideologies of those responsible for the Terror, specifically how they justified their actions, and how these actions were out of touch with the older ideas of socialism and utopia which were seen as naive and unrealistic by the new regime.

– Fainsod, Merle, How Russia is Ruled, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965).

At the time a fairly recent account of the tactics of Soviet rule, Fainsod’s book details many of the policies during the Soviet Terror, and also the characteristics of those policies. Fainsod claims the early days after the Revolution were marked by sporadic bursts of random mob violence which eventually evolved into the coldly efficient tactics under Stalin’s rule. This evolution of political violence ties into Stalin’s consolidation of power, and Fainsod details the role terror played in this consolidation of the regime. He argues establishing the dominance of Stalinist policy and ideology was more important than notions of innocence and guilt, as evidenced by the increasing prevalence of liquidations, until even the secret police (at that time called the NKVD) was subjected to the Purges.

– Fitzpatrick, Sheila, The Russian Revolution, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

This latest edition of Fitzpatrick’s book provides a definitive short history of the events of Revolutionary Russia, from the pre-October years leading up to and through the Great Purges. This book is an excellent overview of the important people and movements of the time, while also providing thoughtful insight into some of the ideologies present during the post-Revolution years. Fitzpatrick believes that most revolutions tend to lose their energy and purpose over time, eventually leading to a return to some semblance of normalcy. This was not the case with the new regime in Russia, as Stalin, Lenin and their followers saw themselves in a never-ending conflict with those who sought to disrupt the new regime. She also asserts that in Stalin’s mind, the Revolution was only over when he said it was, and that it was only he who could claim when victory was won.

– Holquist, Peter, Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia’s Continuum of Crisis, 1914-1921, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002).

Holquist’s book focuses on the tumultuous period from 1914 to 1921 and how the events during this era affected the emergence of the Soviet state. The various expressions of violence that occurred during this time was, in Holquist’s view, critical in how the ideology of the Bolsheviks transformed because of the perpetual class war they found themselves in. Part of this class war was their conflict with the Cossacks, whom Holquist spends much of his book investigating. Holquist describes how the Russian revolutionaries were conditioned to see the Cossacks as their enemies, the brutal footmen of the oppressive Tsarist regime. The “de-Cossackization” policies enacted were enforced in the hopes of creating a utopian socialist state. These utopian ideas were inevitably mixed, however, within an atmosphere of fear and brutalization.

– Simmons, Ernest Joseph ed., Continuity and Change in Russian and Soviet Thought, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1955).

Simmons’ collection of articles and essays reflects the attitude towards Soviet domestic policy and ideology in the immediate aftermath of the death of Stalin. This paper will focus mainly on the writings of Adam Ulam, who details much of the philosophy of Stalinism. This includes the regime’s need for any enemy it could find, a characteristic true of all totalitarian regimes according to Ulam. He also argues that once Stalin had solidified his place at the head of the Soviet state he was able to dictate whatever ideology he saw fit. Ulam debates whether this ideology was loyal to the ideals of Marxism and even Leninism. Ideology was seen as a viable motivator of the Russian people as long as it was Stalin in charge of dispersing the ideology.

The Legacy of Political Violence in Russian Society

– Gibian, George, “Terror in Russian Culture and Literary Imagination”, Human Rights Quarterly, (Vol. 5, No. 2, May, 1983).

This article investigates how Russians have examined the themes of terror and fear through literary works. Gibian describes how the idea of terror has been ingrained in the Russian psyche because of its numerous occurrences over the years. Because this idea of terror is such a part of Russian culture, the works of art of this culture tend to idolize those who suffer; in Gibian’s opinion, this is done so that the people can make some sense of the terrible things that have happened through the perspective of these fictional characters. Gibian pays special attention to the works of Dostoevsky in regards to how he portrayed suffering, and how both sides of any conflict often become consumed by terror. Gibian also believes that Russian society and its people have an internal aggression that they are always struggling to contain, and that they need to find a way to direct this aggression. Unfortunately, the Terror of the post-October years is an instance in which these violent urges are unable to kept under control.

Creating an Atmosphere of Political Terror

– Knight, Amy W., The KGB, Police and Politics in the Soviet Union, (Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1988).

While this book details the actions and policies of the Soviet secret police well after the Revolutionary era in Russia, it still has many viable points in regards to how the secret police during the time of Stalin was run. For example, the secret police, whether it was the KGB, the NKVD or the Cheka, preferred to act in secrecy, but on occasion would use special cases to advance the dogma of the regime through propaganda. Knight also places emphasis on the policies of mass arrests and show trials. Gaining confessions was not about truth but instead about proving the legitimacy of the state. By the time the Purges reached their peak there was little discrimination as to who was arrested and tried.

– Leggett, George, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981).

In this book Leggett focuses on the Cheka and their activities in the immediate aftermath of the October Revolution. Leggett portrays the Cheka as a necessary evil, a group of violent men serving Lenin to rid Russia of all those who would stand in the way of revolution. The Cheka were perhaps the most prominent tool used by the new regime in their quest to create a socialist state at all costs amid what they saw as a never-ending class war. Leggett argues that the main purpose of the Cheka during this time was to act as a force of terror. This was done to both quash any anarchist opposition and to deter any would-be saboteurs. In time, the Cheka would stand and act above the law, a status granted by Lenin and Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder and head of the Cheka.

– Thurston, Robert W., “Fear and Belief in the USSR’s ‘Great Terror’: Response to Arrest, 1935-1939”, Slavic Review, (Vol. 45, No. 2, Summer, 1986).

Thurston’s article is important because it challenges many of the perceived notions about the Terror and how it truly affected the people. Thurston believes, in a twisted kind of way, that the Terror instilled a certain amount of loyalty to Stalin and the regime among the citizenry. It speaks to this perverted loyalty that the country was not broken after the Purges, and Thurston points to the Soviet successes in WWII as evidence that the country was united by Stalin, even if it was by fear. But Thurston by no means condones the methods of Stalin; he argues that people were so terrified by the idea of being arrested that the idea of upward mobility was frowned upon by many, for it was the higher-ups who were the ones most targeted. Thurston also has issues with the traditionally accepted timeline of the Terror; in his opinion, it didn’t fully take hold until 1937. He also argues that before this time, society was not necessarily in a fit of panic over the terror; many didn’t or either couldn’t accept the enormity of the Terror.

Transition in the Time of Stalinism (note: while Gill’s book is the only source listed under this section, material from several other sources are used for this topic; those sources were categorized elsewhere due to their greater emphasis on other topics).

– Gill, Graeme, Stalinism, 2nd ed., (New York: St. Martin’s Press; Houndmills, UK: Macmillan, 1998).

Gill’s book is an extremely concise account of the interwar period and many of the cultural policies that Stalin oversaw including the New Economic Policy, collectivization and mass industrialization. Gill gets into some of the history of the development of the Russian state, referring to both Peter the Great and Ivan Terrible in comparison to Stalin, who Gill sees as a similar modernizer set in a different political climate. Gill also details how the regime abandoned ‘moderate’ methods of coercion after the end of the NEP which would eventually lead to the Great Purges.

The Question of Ideology

– Clark, Katerina, Moscow, the Fourth Rome: Stalinism, Cosmopolitanism, and the Evolution of Soviet Culture, 1931-1941, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011).

Clark’s book is an interesting take on the Soviet Union in the time of Stalin from a cultural perspective. One of the most interesting points made is her idea of ‘masking and unmasking’, a reference to both the theatrical elements of Russian culture and to the philosophy of Stalinist policies such as the show trials. Clark argues that the desire to reveal things as they were (or in the case of Stalin how he wanted them to be) is rooted in Bolshevik ideology and is one example of how Stalin may not have deviated from Marxism as much as some perceived. However, Clark also mentions that the obsession with brutal industrialization and efficiency was an abandonment of the utopian ideology of Marxism.

– Goldman, Wendy Z., Terror and Democracy in the Age of Stalin: The Social Dynamics of Repression, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

This book focuses on many of the social dynamics that were influenced by the Terror, particularly the working class and the unions. One of the main focuses of the book is how Stalin manipulated the social environment for his own ends, including his “support” of democratic elections, which were actually used to draw out his political opponents whom he would eventually crush. Goldman also points out how Stalin used the assassination of Sergei Kirov (which he allegedly ordered himself) to create an atmosphere of even greater fear and terror. Goldman is interested in how Stalin’s approach to enemies of the regime influenced the Terror and allowed it to last longer than it might have. She also examines how Stalin justified the change in ideology from the Revolutionary Bolshevism of October to the Terror of the 1930’s by claiming that victory could not be won until any current and future enemies were eliminated.

– McCauley, Martin, Stalin and Stalinism, (New York: Longman, 1995).

While this book offers a concise examination of the Stalinist era, for the purposes of this paper the emphasis on McCauley will be centered on his observations of the Stalinist views of the class struggle and how they tied into the ideology of the regime. McCauley looks at how, in Stalin’s eyes, the class struggle had a certain ideological relativism, meaning that ideology was applicable in certain areas. One of these areas was the notion of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’. McCauley argues that proletarian dictatorship was another prime example of Stalin turning his back on Marxist thought.

– Stites, Richard, Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

The focus of this book is on the rise and fall of utopian idealism in Revolutionary Russia. Stites documents how the idea of a socialist utopia found its way into nearly every aspect of Russian culture. Reading Stites’ book, one gets a sense of the idealistic spirit prevalent among the Russian intellectual and artistic community. This sense of hope was soon swept away in the rise of Stalin; Stites details how Stalinism was a complete rejection of this idealistic utopianism. In its place, he preached (or rather demanded) a single plan and vision for Russia. This vision had no room for autonomy or spontaneity and no belief in the intrinsic goodness in people. Stalinism was a very cynical philosophy that destroyed any and all links to the utopian idealism of post-October Russia.

Results and Justifications

– Barnett, Vincent, “Understanding Stalinism: The ‘Orwellian Discrepancy’ and the ‘Rational Choice Dictator’”, Europe-Asia Studies, (Vol. 58, No. 3, May, 2006).

This article attempts to make sense of the twisted reasoning behind the Terror with particular emphasis on Stalin. As Barnett sees it, Stalin’s main goal during the Terror was to ‘optimize’ the regime as well as he could. This meant establishing absolute control and eliminating anybody that might pose the remotest threat. Much of Barnett’s argument centers around a comparison between Stalin and Adolf Hitler. Barnett argues that while Hitler was a fanatic who was dead-set on a certain set of ideals, Stalin was simply an arrogant, corrupt and cynical man obsessed with power. Stalin was not a madman: Barnett asserts that he was coldly rational in an atmosphere of lunacy. An important distinction that Barnett makes is the difference between rationality and sanity, irrationality and insanity. In his mind this is what separated the regimes of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

– Rummel, R.J., Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917, (New Brunswick, USA: Transaction Publishers, 1990).

This book examines in great detail the results of the mass killings that have occurred in Russia in the 20th century, especially during the Revolutionary era. This is an excellent source to examine the statistical results of the numerous catastrophes of the Soviet era, as the book is filled with dozens of charts and tables detailing the killings. Much like the Barnett article, Rummel’s book also examines the twisted sense of rationality of Stalinism. He observes how Stalin used any means necessary in order to gain the loyalty of his followers. Barnett also argues that the Terror was a result of the actions of people more so than the policies of the structures of the new regime. An interesting point that is made concerns the belief that the killings of millions of people by a regime requires a certain ideology different from that of the ideology of an individual killer.

Primary Sources

– Mattick, Paul, “Bolshevism and Stalinism”, trans. Andy Blunden, for Marxists.org 2003, Kuasje Archive, (Politics, Vol. 4, No. 2, Mar/April 1947), Marxists Internet Archive, 2009.

Mattick’s essay is part of a collection of his views on Stalinism in relation to similar philosophies such as Bolshevism and Communism from the perspective of a Left Communist. Mattick looks at how Stalin was viewed by his contemporaries, particularly Trotsky. Mattick is critical of how Trotsky seeks to compare the ideology of Stalin to the ideologies of himself and Lenin, while Mattick brings up the National Socialist Party of Germany as an example of evolving ideology and policy. Mattick also argues that by being critical of Stalin, one is also being critical of Lenin.

– Moore Jr., Barrington, Terror and Progress USSR: Some Sources of Change and Stability in the Soviet Dictatorship, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1954).

As a general examination of the philosophy and ideology of Stalin’s regime, Moore’s book is an expansive and in-depth resource. He details how the regime broke off social ties with the people that were not beneficial to their goals. In so doing, the regime had set aside the rationalist and utopian thoughts of the past. Moore argues that the basis of the relationship between political terror and socialism is the balance of interests between certain sets of people, and that socialism by its very nature upsets this balance. The difference with Stalin’s regime was that he took political violence to unprecedented levels. Another issue Moore addresses is how the state was able to survive when it is liquidating so many of its citizens. He argues that there is a point before total institutional collapse where the state can endure while still destroying individuals.

– Stalin, Joseph, “A Letter to V.I. Lenin” from J.V. Stalin, trans. Salil Sen for MIA 2008, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1954, (Works, Vol. 5, 1921-1923), Marxists Internet Archive, 2008.

This short letter from Stalin to Lenin in 1921 serves as a pinhole through which to observe how both men (Stalin in particular), wanted to effect cultural change on a grand scale. Stalin comments on a book he read regarding the ‘Electrification’ of society, and how words were no longer enough to gain the change the nation needed. Stalin talks about ‘practicality’, an early example of how he would come to justify many of his later policies and actions.

– Trotsky, Leon et al., Dictatorship vs. Democracy (Terrorism and Communism): A Reply to Karl Kautsky by Leon Trotsky, (New York: Workers Part of America, 1922).

Written in the early days of post-Revolution October, Trotsky responds to the writings of Karl Kautsky, a German Social Democrat. Trotsky talks about the nature of political transitions, noting that all of these types of transitions have violent aspects to them. These violent aspects are increased in the case of Revolutionary Russia Trotsky argues because of the ‘debt’ that had been left by both the Great War and the Civil War, and how difficult it would be for the Russian people to recover.

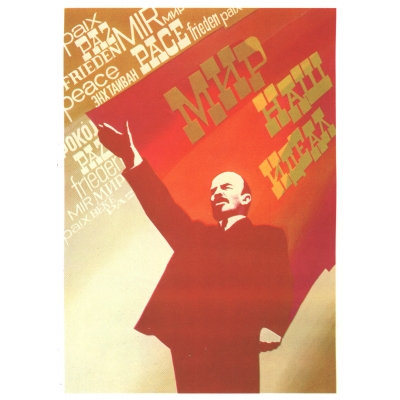

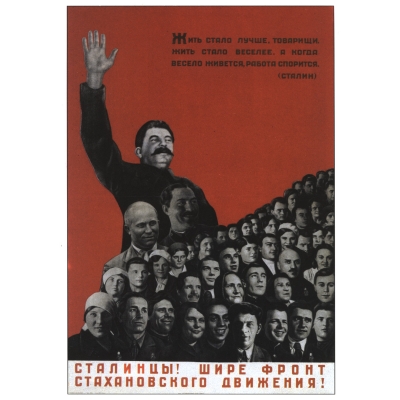

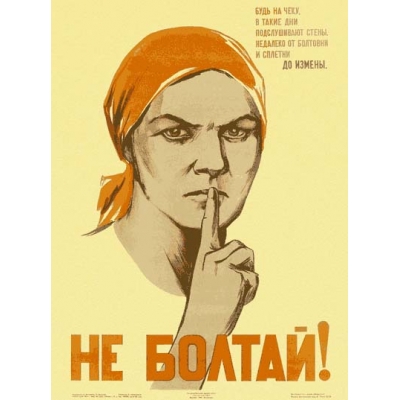

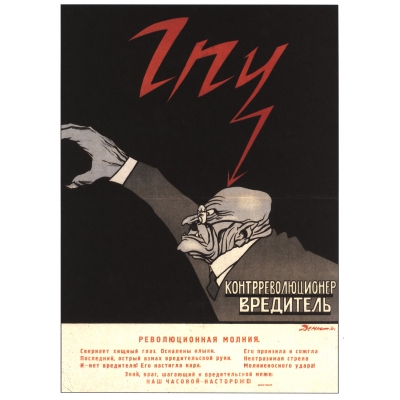

The following images are examples of Soviet propaganda posters from the aftermath of the October Revolution. Propaganda spread amongst the people, particularly visual propaganda, was one of the most effective ways in which the regime asserted control and influence.

-“Peace is our ideal”, SovietPosters, accessed November 14, 2013, http://www.sovietposters.com/showposter.php?poster=187.

This image of Lenin reads “Peace is our ideal” (Мир наш идеал). The Russian text is seen in red, while other variations of the word peace are written outside the flag-like section of red. This is indicative of the fervent nationalism prevalent in Revolutionary Russia, and would become even more prominent in regards to Stalin’s foreign policy.

-“Life’s Getting Better. Stalin 1934.”, SovietPosters, accessed November 14, 2013, http://www.sovietposters.com/showposter.php?poster=152.

The text at the top of this poster reads (approximately) “Life has become better comrades, life has become more cheerful, and when living cheerfully, work progresses.” (Жить стало лучше, товарищи, жить стало веселее а когда весело живется, работа спорится-Сталин). The bottom portion reads “Stalin! Wider front of the Stakhanovite movement!” (Сталины! Шире фронт стахановского движения!). This is a reference to Aleksei Stakhanov, a worker who helped make popular the idea of over-achieving in work. Here Stalin is seen preaching the benefits that hard work will (and has) brought about in the new Russia. This was merely another of Stalin’s fronts, as he was often in conflict with workers who went on strike and those who were allegedly “wrecking” the new socialist state.

-“Do not speak out!”, SovietPosters, accessed November 14, 2013, http://www.sovietposters.com/showposter.php?poster=17.

The upper portion of this poster reads “Be on the alert, in these days listen through the wall. Not far from chatter and gossip is treason” and on the bottom “Do not chatter!” (Будь на чеку. В такие дни подслушивают стены. Недалеко от болтовни и сплетни до измены. Не болтай!). This is a clear example of the true nature of everyday life of post-revolutionary Russia: a place where fear and paranoia ran rampant and everyone suspected everybody else. This poster also has a much more barren look than the previous two.

-“GPU. counter-revolutionary saboteur.”, SovietPosters, accessed November 14, 2013, http://www.sovietposters.com/showposter.php?poster=138.

Much like the previous example, this poster represents a warning directed at the people regarding the “threat” of saboteurs by the GPU (ГПУ). It declares this man a “counter-revolutionary saboteur” (Контрреволюцонер вредитель). The bottom portion describes how this man will attack the state, with “predatory eyes that sparkle” (Сверкает хищный глаз) and a “sharp swing of his wrecking hands” (острый взмах вредительской руки). But in the end, he is “not a wrecker! He was consumed by punishment” (нет вредителя! Его настишла кара). The poster concludes with a warning to “know the enemy” (Знай враг) and declares that this “our time of alertness! (Наш часовой – настороже!). It is not the words that convey the strongest message in this particular poster but rather the imagery: the saboteur is portrayed as an inhuman beast, with the symbol of the GPU pointing directly at him in a very accusational manner.