Jenna Abbot

Traditional Gender Roles and

Female Political Participation in Russian Society

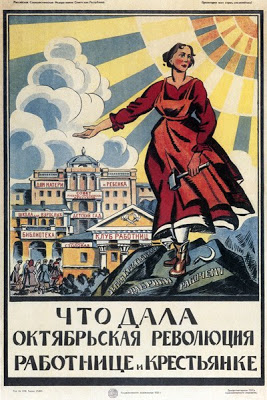

"Chto dala Oktiabr'skaia revoliutsiia rabotnitse i krest'ianke" (What the October Revolution Gave Worker and Peasant Women)

Introduction

The purpose of this research guide is to explore the lives of Russian women from 1890 to 1940. The guide aims to explain the conditions of political atmosphere, home life, and work opportunities that garnered a desire for female political participation and fostered organizations for such a cause. It explores the development of women’s rights and advocacy within the context of pre-, during-, and post- Revolutionary Russia. This tumultuous time period brought many questions of equality to the surface and its radical changes for Russian citizens allowed for many opportunities for women to surface.This guide also provides distinctions between female life in rural and urban areas, as geographic location played a large role in determining type of involvement and level of participation.

Women in pre-Revolutionary Russia lived in an extremely patriarchal system. Most married at a young age, and upon marriage were entirely devoted to their husband’s family, welfare, and success. Prior to the revolution, there was little opportunity to gain governmental support for change. Most feminist groups were based in more urban areas, and those that formed during this time period were radical and would later align themselves with Social Democrat or Kadet causes. These groups formed a constituent base in a “grassroots” manner, seeking support from their peers, friends, and families. Most desired the right to vote, own property, seek divorce, and gain higher education. These women held the All-Russian Congress for the Struggle against the Trade in Women to tackle the immoral problem of prostitution, and gained the right for higher education in medical and pedagogical establishments in 1911. It was not until WWI that women gained the momentum and the arena to promote their more radical beliefs, and work within the government system itself.

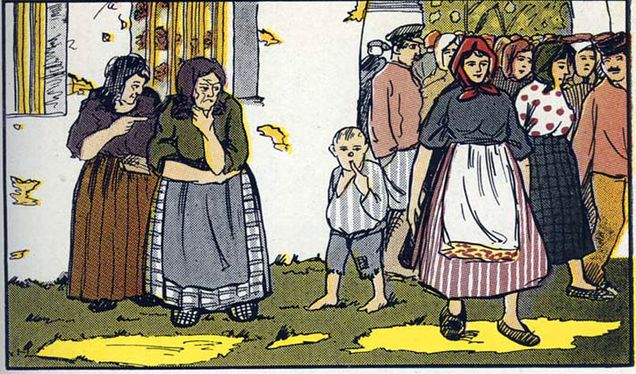

Throughout World War I, the Revolution, and the Civil Wars that ensued, women were asked to take on the roles previously only offered to men. The rise of industry during this time period also encouraged many women and families to move to the cities, and allowed for women to participate in “man’s work” on the shop floor. While job opportunity lended itself to the equality movement for women, this was not the intentional goal of the Bolshevik government. Although they promised women equal citizenship, they did so with the intention of creating a unified base for Socialist programs. Consequently, there was little government aid to distinctly feminist groups, as they believed that too much division by gender would hurt their overarching goals. While city women became assimilated into the proletarian lifestyle, the government recognized the need for programs within rural communities. Groups like the Komosol and Zhenotdel were dedicated to improving the “backwards” qualities of women. Instead of advocating the radical beliefs of the Bolshevik party, Zhenotdel women described the social services the party could provide: childcare, communal meals, etc. While these aspects may have sounded appealing to many women, there was a strong backlash to Communist ideas. Most women living in rural communities (and many living in urban ones, for that matter) resisted the changes imposed by the new regime. Additionally, the social changes advocated by the party became infeasible for because they imposed a “double burden” on Soviet women: They could not avoid the domestic duties of childbirth, and in times of economic hardship they had to provide childcare and attend to household chores. This left little time for active participation in the party, and consequently they never were to be considered the equals of men.

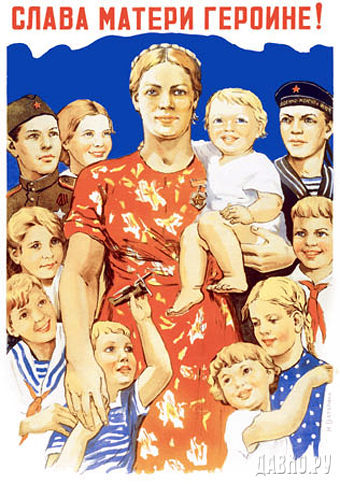

When Stalin gained power in 1930, he declared the “woman question” solved. His policies led to a “Great Retreat” in all aspects of Soviet culture, including the reinstatement of traditional roles for women. As jobs became more scarce, women assumed the roles of “mothers of Soviet Russia”. They were seen as a nurturing support system, rather than as equal advocates for a growing nation. The obshechestvennitsa movement, or the wife-activists movement became a popular group for female involvement. This time period was categorized as a return of women to the byt (the private sphere), and led to a decline of involvement in feminist causes.

The following compilation of sources includes information on:

- the typical lifestyles of women during the 1890-1940 time period

- Feminist groups and women’s political organizations

- Female advocacy for the Bolshevik cause

- Female participation in Bolshevik programs

- The contradictions of Bolshevik programs for women and reasons for their ineffectiveness

- Reasons for and documentation of the “Great Retreat” to traditional gender roles under Stalin.

General Background Information on Women and Political Efforts

Evans, Richard J.. The feminists: women’s emancipation movements in Europe, America, and Australasia, 1840-1920. London: Croom Helm ;, 1977.

Evans describes a comparative history of feminist movements, a feat not easily accomplished for an eighty year time period. He provides an interesting means of examining the success and failure of the Russian women’s movement within the larger context of global women’s movements. He also provides interesting similarities between the two, which make some concepts easier to understand. Of particular interest are the second part, which has an individual section of Russian feminism, the third part which explains socialism and feminism, and the fourth part which examines the affect of the First World War on feminist movements.

Noonan, Norma C., and Carol Nechemias. Encyclopedia of Russian women’s movements. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2001.

This volumed is organized into 3 time periods: 19th and 20th c., the Soviet period of 1917-1991, and the transitional era (post 1985). The first and second sections would be beneficial for researching specific feminist groups, important leaders, and the publications and media produced by the Russian feminist movement over time. The compilation of movements emphasize Bolshevik policies of “gender equality”, and the authors comment on how women are depicted as almost-men, and that the roles of a revolutionary work are gender-marked to promote male domination. The work also provides a general timeline of important dates within the movement, which serves as a good reference point for researchers.

Sperling, Valerie. Organizing women in contemporary Russia engendering transition. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

This book examines the later state of feminism in Russia, and traces movements back to the revolutionary time period. Sperling portrays the growth of different advocacy groups and explains the difference in the intentions of each. She focuses her examination on city-based groups in Moscow, Ivanvo, and Cheboksary. A heavy emphasis is placed on delineating differences between state-run/affiliated feminist organizations, and those formed from an indigenous or grassroots background. Sperling’s research would provide detailed analysis of the efforts of urban women to gain rights and equal standing.

Stites, Richard. The women’s liberation movement in Russia: feminism, nihilism, and bolshevism, 1860-1930. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Stites provides a chronological account of feminist movements in Russia, and shapes his evaluation into thematic chapters such as “Women and Tradition”, “Socialist Women’s Movement”, and “Sexual Liberation”. He provides detailed background information about the underlying causes of discontent for women, and then traces the many faces and names associated with the Women’s Movement. Stites also gives examples of the backlash against such movements (from men and women), and dedicates an entire chapter to the Sexual Revolution. This book makes for a strong source, as it provides clarification of confusing concepts and names (i.e. the many Revolutionary parties and their position on women, and the difference between stages of the proletarian women’s movement). This book is cited as a source in almost every other popular text on the topic, demonstrating its usefulness for research.

Women’s Life in Pre-Revolutionary Russia

Edmondson, Linda Harriet. Women and society in Russia and the Soviet Union: selected papers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

These thesis papers examine the growth of a feminist movement within Russia, and compares its accomplishments with similar movements outside of Russia. The book provides information about the political climate of Russia during the rise of these movements, and also discusses Russian women’s participation in international suffrage movements such as the International Council of Women and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. Finally, it examines the state of the movement leading into the Revolution. Contrary to many popular books on this topic, Edmonson’s “concern is with those women whose best efforts were all too soon eclipsed by the revolution” (iii) as she focuses on non-violent movements.

Engel, Barbara Alpern. Between the fields and the city: women, work, and family in Russia, 1861-1914. Cambridge [England: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

This book chronicles the hardships faced by Russia’s peasant population after their emancipation, especially as they struggled with the changes presented by the rise of industrial labor. Engel explains how this need to emigrate for work loosened the strictness of patriarchal peasant society, and allowed for peasant women to eventually become a large portion of Russia’s “working class”. She analyzes formal complaints about domestic issues/gender roles lodged with local courts by the peasants themselves. She also describes the major shifts encountered by peasant women after migration, and how city life perhaps did not provide as many opportunities as it was suggested it could.

Kelly, Catriona. “Teacups and Coffins: The Culture of Russian Merchant Women, 1850-1917..” In Women in Russia and the Ukraine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

While Marsh’s entire compilation is filled with interesting essays pertaining to the struggle of Russian and Ukrainian women for equal rights, Kelly’s essay is of particular interest. Instead of focusing on women as “victims”, she highlights women who found great success during the revolutionary time period: female merchants and factory owners who benefited from capitalism prior to its fall. She strives to depict a different kind of woman from those images commonly circulated- of naive, incapable, and “unenlightened” Russian women.

Maxwell, Margaret. Narodniki women: Russian women who sacrificed themselves for the dream of freedom. New York: Pergamon Press, 1990.

Maxwell discusses the early feminist movements associated with the Populist (and later Socialist Revolutionary) movements. Her book claims that the later Soviet ideal of the revolutionary woman contrasted greatly with the Bolshevik women that promoted feminist causes prior to the Revolution. Maxwell asserts that these characters are forgotten by history, because they do not fit the form of the “dutiful and dull” women portrayed in later accounts. The book traces the lives and works of several women, and thus is useful for biographical information as well as for research of different perspectives on the women’s liberation movement. It provides lesser known accounts about the original Russian feminists.

Rosslyn, Wendy. Women in nineteenth-century Russia lives and culture. Cambridge: OpenBook Publishers, 2012.

This anthology of essays provides a good historical context for examining the changes in the daily lives of women throughout history. Of particular interest is the first chapter on Women and Urban Culture (by Barbara Engel).Unlike the other sections which largely focus on more abstract aspects of culture (i.e. art, writing, and violence encountered by women), this essay focuses on the confines in which women were working between 1855 and 1881. Engel illustrates that although urban life is conceived by history to have been much more progressive, it was still extremely difficult for urban Russian women to break out of their traditional positions in society. This source would be useful for comparison purposes of city and country life, and its other chapters lend themselves to a closer examination of women’s involvement in the arts.

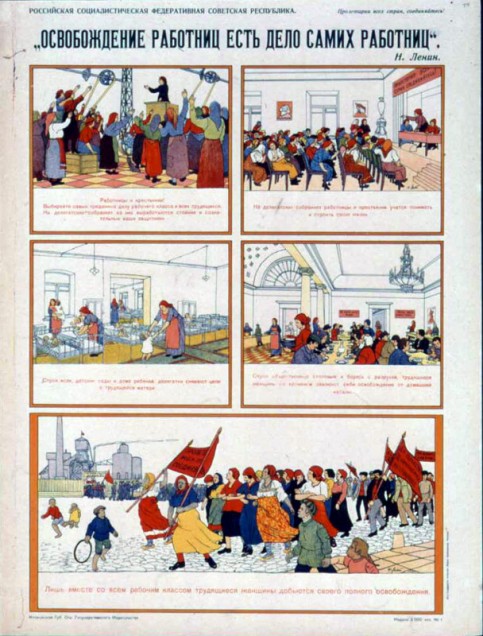

7 frames depicting the Bolshevik plan for women's liberation. However, the last line reads "Only together with the entire working class will working women achieve full liberation", emphasizing the insignificance given to the women's movement alone.

Female Roles and Rights in the Revolution-Era

Bonnell, Victoria E. “The Representation of Women in Early Soviet Political Art.”Russian Review 50. no. 3. (1991): 267-288.

This article examines the difficult time that propagandists and Soviet artists had defining how women should look and what roles they could have in art. Few women were depicted in early Soviet art, partially as a reaction to visual trends in pre-Revolutionary Russia. Bonnell explains the transformation of female imagery from allegorical representations to depictions of the ideal female Bolshevik worker. She also provides an analysis of the Bolshevik party’s attempts to separate from Old Regime ideals through the lens of art. This work gives specific examples of posters for researchers to reference. There is a special section devoted to depictions of peasant women, which could be useful for examining their specific role within the context of Revolutionary Russia.

Clements, Barbara Evans. “Working-Class And Peasant Women In The Russian Revolution, 1917-1923.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 8, no. 2 (1982): 215.

Clements describes the role that women from both the country and the city played in the Bolshevik takeover of the Russian government. She finds this significant because their responses to this event “reveal much about their beliefs, loyalties, and fears about their positions and roles in the social system.” In the face of political turmoil, peasant women found it more important than ever to have a husband and family, and few stepped away from the confines of tradition. By contrast, working women lived in the cities- which had been “weakened by traditional values”. Clements writes that despite these distinctions, urban women were not that far-removed from peasant women, as most of them had emigrated from the countryside. She examines how the Bolsheviks attempted to coerce both groups of women to accept the new ideology. This book is beneficial for background information about how quickly and through what means Bolshevik ideology reached certain groups of people. It also describes how the Civil Wars became a huge obstacle for the perpetual of Bolsheviks programs, as most of the population faced large suffering during this time period. Clements summarizes that most women did not connect to the Bolshevik ideology, and those that pursued it did so to ease the burdens of their traditional roles (childcare, food, etc.) than to assume new “revolutionary” roles. This work would be helpful for studying the perpetuation of ideas within the two groups of peoples and for comparison purposes. It also provides readers with a good understanding of the oversights of Bolshevik programming.

Edmondson, Linda Harriet. Women and society in Russia and the Soviet Union. Cambridge [England: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

This is an extremely useful compilation of essays pertaining to the subject of women’s rights movements and popular involvement prior to, and following the Russian Revolution. Although the works are arranged in a relatively-chronological order, there is no central theme that unites them. Topics range from depictions of women in the media and the use of sexist and crude jokes within popular culture, the development of women and the arts (authors in literature), growth of women into professional fields as a result of WWI, as well as the arguments raised and groups formed by various feminist groups at different time periods. This would be an appropriate resource for a study of women within a cultural context, as well as an analysis of the goals of Russian feminists. Because each section is a short essay, this source would best be paired with broader texts for the reader to fully understand each concept.

Goldman, Wendy Z.. Women, the state, and revolution: Soviet family policy and social life, 1917-1936. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Goldman provides a detailed account of the implementation of the Bolshevik ideology surrounding women. Like many books focused on the same topic, she stresses the change in ideas of “Family”- while the party first promoted the “withering away” of such bourgeois ideas, it later realized that women were necessary for a mothering role. Goldman examines the effect of such policies on women and children. This would be useful for those researching changes in family life specifically, or for a more extensive study on how women’s roles were perceived by the Soviet government.

McDermid, Jane, and Anna Hillyar. Women and work in Russia, 1880-1930: a study in continuity through change. London: Longman, 1998.

This book is an analysis of changes for women in the workforce over time, especially as a result of the abolition of serfdom in 1861 and the push for industrialization beginning in the late 1890s. McDermid and Hillyar examine the differences in work opportunities for peasant and urban women, as well as the impact of the accessibility of education for higher-class women (which allowed them more options for professions). Special detail is given to the interaction between “gentry women and their social inferiors” as a result of female labor. It appears important to McDermaid and Hillyar that the hardships faced by women during this time period not be discounted. They aim to prove that women had many factors working against their ambitions to elevate their status. This will be beneficial for research examining female class relations and the growth/decline of opportunity for women as a result of political decisions. There is also a chapter dedicated to the female role in WWI, which allows is applicable to the pre-revolutionary category.

Stockdale, Melissa K.. “”My Death For The Motherland Is Happiness”: Women, Patriotism, And Soldiering In Russia’s Great War, 1914-1917.” The American Historical Review 109, no. 1 (2004): 78-116.

Stockdale examines the eagerness with which many Russian women met World War I. Her article emphasizes the role of the Women’s Death Battalion (Zhenskii batal’on smerti), which established the idea that women could fight alongside men. Total mobilization of the country meant that women were asked to perform tasks and jobs unlike any they’d been previously allowed to take on. Many believed that equal citizenship and treatment would be a result of such labor. Ironically, Stockdale writes that this original unit was in fact founded to “embarrass” male soldiers into doing their jobs, lending less credibility to the liberating aspects of the Death Battalion. Is important for research because it demonstrates early ambitions of women to achieve equal status. It also is interesting for those researching rural versus city women, as it describes how vested interest in the preservation of their state unified women of many classes and backgrounds .

Women in the Soviet Union: A Return to Traditional Roles

Brown, Donald R.. The Role and status of women in the Soviet Union. New York: Teachers College Press, 1968.

This anthology of essays was compiled within the context of Cold War policy as well as the rise of second-wave feminism within the United States. This background may create a unique (and perhaps, biased) account of the Soviet woman. It questions the root of the “woman question”, and contemplates whether women could have possibly shed their domestic roles completely, given that they are biologically predisposed and solely responsible for reproduction and the perpetuation of society. Additional topics discussed include: the balance between motherhood and labor (with several helpful tables regarding population, gender, and allocated time for work), the average life of female students, women in literature, and the ideals behind women and family/marriage roles.

Fuqua, Michelle V.. The politics of the domestic sphere: the Zhenotdely, women’s liberation, and the search for a novyi byt in early Soviet Russia. Seattle, WA: Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies, Univ. of Washington, 1996.

Furqua chronicles the rise and fall of the Zhenotdely, an organization designed to improve the “backwardness” of Russian women and encourage them to become productive members of Soviet society. She explains the external struggle of the Party to coerce women into joining, as well as the internal struggle over the benefit of the zhenotdely. Many within the party believed that such organizations were contradictory towards the Bolshevik cause, as they segregated women instead of uniting all citizens together. This book examines the time span between 1919 and 1928, with special emphasis on the consequences of the New Economic Policy on the book. This information would be applicable to any research pertaining to women in the home, the concept of the “byt” (private sphere), and the internal Soviet debate about the place of women within society.

Gorsuch, Anne E. . “‘A Woman Is Not a Man’”: The Culture of Gender and Generation in Soviet Russia, 1921-1928. ” Slavic Review 55, no. 3. (1996): 636-660.

Gorsuch explains why young girls were reluctant to participate in political life of revolutionary Russia. They were overburdened by household responsibilities, parental scorn, and a quick decline in promised collectivist resources (cafeterias, kindergartens). She focuses on the Komosol and the women that did participate in it. She also suggests that another reason for decreased participation was the masculinized culture of the organization. This article places its focus on the youth growing up in this culture (as this is who the Komosol was designated for). She explains that joining such a club meant that they would not fulfilling their duty to their families- a concept girls had difficulty grappling with, while boys didn’t mind. The ideal young communist led a youthful and unencumbered life, and was able to dedicate the entirety of their time to the cause- this was virtually impossible for young Russian women. This source would be helpful for examining gender relations and the struggle of achieving equality within the Party.

Holland, Barbara. Soviet sisterhood. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Holland provides an anthology of essays written by nine female historians, who traveled to Russia together prior to compiling this book. Holland emphasizes their emotions of solidarity and connection with the feminist cause throughout her commentary. Together, they examine the Soviet claim of gender equality, and examine the falsity of such claims through different aspects of culture. Topics applicable to research include history of a male-dominated government, traditional feminism, Soviet literature and magazines as propaganda for women, as well as those that follow the “double burden” view- unfair working conditions for women, rural Soviet women, and the conflicting views on state-run childcare.

Neary, Rebecca Balmas. “Mothering Socialist Society: The Wife-Activists’ Movement And The Soviet Culture Of Daily Life, 1934-41.” Russian Review 58, no. 3 (1999): 396-412.

After the retreat of women back into the home in the early 1930s, new avenues of feminism began to arise. Neary discusses the wife-activists’ movement (the obshechestvennitsa movement) which encouraged domestic roles for women, and asked that they volunteer their time for only social services. The article tries to reconcile this movement as not a retreat to typical gender roles, but as an example of what the new “Soviet” woman hoped to become.

Tostikova, Natasha and Scott, Linda. “‘The New Woman and the New Byt’: Women and Consumer Politics in Soviet Russia.” Advances in Consumer Research 28. (2001).

This article demonstrates the connection between Russian female life and consumer desires, and the Marxist regime’s attempts to eliminate factors of each. The authors explain the concept of the “byt” or the sphere of private life attributed to females during this time period. The article provides examples of short stories that promoted gender equality as a solution for female domestic problems, and demonstrates how an image of the “New Woman” was created in material terms- she was identified by her clothing and was supposed to possess little objects, decorations, etc. These practices encouraged the idea that the ideal of beauty was fitness not makeup. The authors examine material good availability, and point out that there was a lack of those goods that were making housewive’s jobs easier in Capitalist countries, so women had to spend more time than ever in the home to accomplish the same task. This source is useful because it explains the affects of the New Economic Policy on women, and provides useful information about the Zhenotdel.

Vesela, Pavla. “The Hardening Of Cement : Russian Women And Modernization.” NWSA Journal 15, no. 3 (2003): 104-123.

Vesela argues that the rise of Stalinism was the result of a need to deal with changes to the traditional gender order that occured in the 1920s. Vesela relates real historical ideas to fictional ones, as she describes how Gladkov’s Cement was edited over the course of these years to reflect the correct version of gender theory for the time. This article is useful for the study of the “Great Retreat” and its affect on both the expectations and the depictions of women.

Useful Primary Sources

Gladkov, Fedor. Cement: a novel. New York: F. Ungar, 1960.

This story demonstrates the changes in relationships, families, and daily lives that the Soviet regime imposed. Gleb, a soldier returns home to find his entire world turned upside down, and that his wife (Dasha) has become a “comrade woman”. Gladkov’s tale represents changing ideas about womanhood and provides a fictional account of the transition to a “New Woman” and a “New Man”.

Kollontaĭ, A.. Red love,. Westport, Conn.: Hyperion Press, 1973. 1927.

A fictional novel written by Kollontai to narrate her political beliefs. The main character Vasia, a Bolshevik woman who is in love with a fellow conrad, Volodia. Their relationship becomes complicated as a result of political ties and changing views about love and relationships within the party. Kollontai’s own political agenda is obvious throughout, thus this work would be useful for studying her contributions to the feminist movement.

Krupskaya,Nadezhda K. “Young Pioneers: How Women Can Help”. Women’s Weekly. 1925. Marxists Internet Archive. 2009.

Krupskaya promotes the idea of young children aiding the Communist cause. She declares that children should work closely with women’s worker organizations. She also mentions that both boys and girls should be recruited equally, an interesting point for the feminist perspective. This would be interesting for those studying Soviet childhood, and the influence of Komosol programs.

Lenin, V.I. The Emancipation of Women. New York: International Publishers. 1969.

Lenin details his beliefs about the common problems posed by society that kept women limited, and the need for equal gender in Russia. While he agrees with some feminist ideology and describes the oppressed state of female opportunity, he does not necessarily advocate for the feminist movement in total. Instead, he declares that the emancipation of women is necessary to promote the Socialist cause as a whole. He summarizes that women are expected to join the proletarian cause, and to do so they must be treated like other male proletarians. This would be useful for learning about Marxist theories on women and feminism, and is very applicable to the variety of topics discussed in this research guide.

Zetkin, Clara. “Only in Conjunction With the Proletarian Woman will Socialism be Victorious” in Selected Writings, trans. by Kai Schoenals, International Publishers, 1984.

One of the first “Bolshevik” women, this essay was written to implore others to join a proletarian Russian woman’s cause. She discusses the rapid industrial movement that brought women outside of the context of the home and her belief that they have been conned and cheated within such a capitalist system. She is eager to separate the proletarian women’s cause from that of “bourgeois women”. Her answer to these dilemmas is to end capitalism , and as a result true equality will be attained. Her writing provides an interesting perspective, as it meshes feminist equality with overarching political themes for her time.