Constructing a Curriculum: 21 Days towards Unlearning Racism and Learning Antiracism

Sasha B. Goldman, Professional Development & Postdoctoral Affairs, Boston Univesity

Design Concept and Foundation

Professional Development and Postdoctoral Affairs (PDPA) at Boston University (BU) takes a holistic view of professional development in the sense that we do not confine our training or resources to hard skills or workforce development. Instead, we create programs that aim to support the individual to develop as a whole human and professional. A core value of our office is that we provide the doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers that we serve with access to professional development and learning resources that will help them contribute to building a more inclusive and diverse academic and research-training environment for the future.

In May 2020, I stepped into a role within PDPA: Program Manager for PhD Professional Development. The primary responsibility of my role is to build and implement a new professional development curriculum for BU’s doctoral students. However, weeks after starting the position, it became apparent that there were much more pressing curricular needs for the populations we serve as a result of both the COVID-19 epidemic and the growing attention to a much longer epidemic plaguing our country – that of systematic racism.

The wellspring of resources on antiracism that began circulating on the internet and in various institutional and interpersonal communities in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in May 2020 was overwhelming for many. Throughout late May and June, I had friends and colleagues reaching out often to ask for resources or direction on where to start reading amongst the titles that were appearing on reading lists everywhere. More pressingly for my professional work, there were approximately 3000 doctoral students and postdocs that we support looking for similar guidance on how to educate themselves to become better allies, researchers, instructors, colleagues, and mentors for communities of color both within and beyond their academic roles.

Many of the crowdsourced or open-access lists that were circulating included excellent resources and had been assembled by allies, advocates, and experts with far more experience working in antiracist education than myself. However, as an educator looking through these lists as instructional content, I found them to be challenging entry points for this material, especially within the context of 2020, which was overwhelming for many. While comprehensive reading lists circulated, they often neglected to structure their content thematically or give much background or context, making the lists somewhat impenetrable for those entirely new to the topic of antiracism or without time to read several challenging books on the topic (see Appendix for a non-exhaustive list of these lists).

There were two recurrent issues that I found with many of these resources. First, they did not provide clear scaffolding for how to build learning in this area over time, an essential component of meaningful allyship and sustained engagement in this type of education. Adequate scaffolding should provide intentionally progressive learning material that is carefully organized and structured to support continued learning and development as individuals build capacity and knowledge around the content. Second, few lists that I encountered provided a substantial array of content for diverse types of learners or those approaching their education in antiracism from a variety of starting points. Take for example, some of the reading lists developed by universities in response to the demand of their student, faculty, and staff populations looking for resources from their institutional experts (see Appendix). These were typically compiled either by faculty in academic departments or staff within offices of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. Many such lists contained prominent titles ranging from the semi-autobiographical, How to Be an Antiracist (Ibram X. Kendi), to the more scholarly Caste: The Origin of Our Discontents (Isabel Wilkerson), and some contained other types of media to engage with such as the award winning “1619” podcast (Nikole Hannah-Jones) or the documentary film “13th” (Ava DuVernay). While helpful to have field experts provide references to titles and resources that they have evaluated, what these lists did not provide is adequate scaffolding for the content that would help learners build knowledge over time.

Beyond these content and structural issues, in the flurry of conversations that arose in the summer of 2020, I saw few programmatic approaches that offered structured learning along with accountability measures. Countless organizations and individuals shared messages or black squares on social media, stating their commitment to supporting communities of color and denouncing racism in all its forms. Many took further steps of beginning to educate themselves on the issue of systemic racism and their own privilege, either alone or in community with others. Some took action by joining demonstrations and protests, by registering to vote, by donating to organizations like Black Lives Matter or Stop Asian Hate, or by finding local black or minority owned businesses to support. And these gestures constitute meaningful actions that do take steps towards dismantling, on an individual level, the perpetuation of racist attitudes and structural inequity. But unlearning racism and learning antiracism is not a linear process nor does it take root simply through engagement with a handful of bestselling titles or a few concrete actions. Systemic racism pervades every aspect of our American culture; it infiltrates our thinking and our interactions, both consciously and unconsciously. To counter the stronghold that structural racism has on our daily lives, our individual commitments to allyship must also become a feature of daily life. Without proper scaffolding and a clear progression for capacity building in any type of learning, learners can lose interest. Therefore, what is needed is a structure for these resources that would support long-term engagement with the content.

Framing and Materials

Making social justice work a feature of everyday life is the underlying principle of the 21 Days of Unlearning Racism and Learning Antiracism curriculum that I developed, with the collaboration of my PDPA colleagues, in June of 2020. The program was organized around the concept that, in order for us all to become better allies and antiracist individuals, we must make the work of becoming actively antiracist an integral part of our everyday lives.

Our model for this project was Dr. Eddie Moore Jr.’s “21-Day Racial Equity Habit Building Challenge,” developed in 2014 by Dr. Moore and Debby Irving. This challenge centers the popular theory that forming a habit takes 21 days of consistent, daily engagement with a particular behavior. Scientific studies have debunked this popular theory, indicating that there is considerable variation in how long it takes people to change habits and that missing one day of performing a behavior does not significantly affect habit formation (Lally 2010). Nevertheless, consistent, sustained engagement is key. As Moore’s website description reads, “creating effective social justice habits, particularly those dealing with power, privilege, supremacy and leadership is like any lifestyle change. Setting our intentions and adjusting what we spend our time doing is essential. It’s all about building new habits” (America and Moore). Their challenge provides a list of resources as well as a tracking chart for learners to mark how they engaged on a particular day, and gives space for reflection on their learning. We used this challenge as a model both because it provided some categorization for its resources, which were organized by media/engagement type (read, listen, watch, notice, connect, engage, act) and length of time required (short, medium, and long), but also because it also prioritized reflection, an essential feature of metacognition that supports learning and knowledge growth. What this challenge lacked for me, however, were two elements: (1) a tiered learning model that would offer entry points into its content from a variety of learning levels and (2) thematic organization of its content. And this is the primary reason why I elected to develop my own 21-Day curriculum, rather than simply running a 21-Day program using Dr. Moore’s plan.

My doctorate is in contemporary art history, and I often think of my current work in the terms of that discipline. The title of curator has been applied to many types of figures in the art world throughout its evolution as a role. In addition, although in my position I do not perform the typical responsibilities of a curator – to oversee, protect, handle, or select works of art for display to the public – in my capacity as an educator, I think of myself as a curator of resources. So, I approached this project with a curatorial mindset when I began work on it in June 2020. This meant that I began with researching the material, using the many lists that I had encountered and new ones that I found through additional research as a starting point for constructing this new learning resource. Although my own personal commitment to social justice work and my engagement with antiracism content through my research has contributed to my education on this topic, I am by no means an expert in this area, and had not read, watched, or listened to many of the titles on these lists; nor did I have the time to meaningfully do so in the process of building this resource. Instead, I did what researchers do and critically evaluated the resources based on the descriptions, reviews, and commentary provided by other scholars, using that evaluation to create a structure and organization for the materials that would be easily accessible and readable for learners.

This initial phase of work resulted in a comprehensive document that somewhat resembled an annotated bibliography, combining and thematically organized the many recommended titles and resources I encountered. Most of the content I included was available online, via open access platforms or sites, to make the material in our program as accessible as possible. From that document, themes and topics began to emerge that would eventually form the first level of structure for our program: daily topics for each of the 21 Days (see Table 1). These topics aimed to provide content for learners to begin to understand the basic origins and history of anti-Black racism and the systems within our society that racism pervades. This was not an exhaustive list of topics or social and cultural structures affected by systemic racism. Instead, it attempts to provide a means for engagement with resources around specific themes, much like one might in a structured course, to give some direction to learners who might have interests in certain topics or systems. We also built in two “Reflection” days and two “Choice” days into the program, at five-day intervals. We encouraged learners to reflect on their learning, to revisit challenging materials and find answers to lingering questions, or to choose another resource from a previous day to engage with on those days.

It is important to note that the first iteration of this curriculum focused generally on anti-Black racism, with content geared towards white and non-Black people of color (NBPOC) learners. Although not designed to exclude individuals who identify as Black, Indigenous, and Brown People of Color (BIPOC), in retrospect, this was not the most inclusive approach. The 2021 iteration of this program, which I discuss below, expanded its view to include additional resources on other communities of color.

Table 1: Daily Topics for 21 Days of Unlearning Racism and Learning Antiracism (2020).

| Day | Topic |

| Day 1 | What Does it Mean to be Anti-Racist? |

| Day 2 | What is Racism? |

| Day 3 | Origins and History of Racism |

| Day 4 | Implicit Bias, Microaggressions, and Stereotype Threat |

| Day 5 | Reflection Day |

| Day 6 | Racial Identity |

| Day 7 | White Privilege and White Supremacy |

| Day 8 | Intersectionality |

| Day 9 | Racial Wealth Gap |

| Day 10 | Choice Day |

| Day 11 | Class and Capitalism |

| Day 12 | Racism in Education + Academia |

| Day 13 | Public Health |

| Day 14 | Criminal Justice |

| Day 15 | Reflection Day |

| Day 16 | Voter Suppression |

| Day 17 | Housing Segregation + Redlining |

| Day 18 | Environmental Racism |

| Day 19 | Food Systems |

| Day 20 | Choice Day |

| Day 21 | Allyship/Next Steps |

The next layer of organization was one that many resource compilations use: categorizing the resources within each topic by media type – content to read, watch, or listen to, and ways to connect via social media. Structuring material in this way appeals to different types of learners who may engage better by listening to a podcast conversation than by reading an article. This approach also provides a means of engagement with each of the topics through the medium that most learners already use regularly, like watching YouTube videos, listening to podcasts, or following activists on social media. Building engagement with antiracist resources into an existing daily practice that many of our doctoral students and postdocs already engage in offered a low stake point of entry and one that might have better longevity. I also added in a concrete action, related to the daily topic, that learners could take each day. Actions ranged from taking Project Implicit’s Racial Bias Test to using research tools like the Pioneer Institute’s MassAnalysis Benchmark tool to see how school funding is allocated in Massachusetts communities.

The final structural element is where I think our program differed the most from existing resources. Within each topic and media category, the material was organized into three options, based on learning level or time commitment (see Fig. 1). Option 1 typically included between 8-12 links and was designed for those looking for introductory material for each topic. Option 2 offered 6-8 links and was recommended for learners who had more background knowledge on the subject or time to engage or was available to those who had worked through all of the material in Option 1. Moreover, Option 3 provided a recommendation of one title or resource per category for participants who preferred to focus on one book or topic for an extended period during the 21 Days. We also included additional resources for each topic, for future learning.

Installation and Implementation

In order to make the resource as accessible as possible, I built a shareable Google spreadsheet to house the program material. Each daily topic was given its own sheet within a larger workbook. There is an overview page at the front of the resource that provides a list of the daily topics, and some directions for how to use the workbook; the second sheet is a tracking chart, adapted from the America & Moore tracking sheet, that we encouraged participants in the program to download and use daily, highlighting the importance of reflection for growth in the process.

We circulated information about the 21 Days program in mid-June via our regular newsletters to doctoral students and postdocs, which go out bi-weekly, as well as through targeted messaging to student and postdoc organizations. We were clear in this messaging that we would be releasing content five days at a time, so that we could gather and respond to feedback on the materials, based on the needs of our participants, in real time. The original title for the program was “21 Day Antiracism Challenge” and the 21 Days were scheduled to begin on June 24, in alignment with Boston University’s “Day of Collective Engagement.” We initially created a registration page just for doctoral students and postdocs, but soon opened registration to faculty and staff who expressed interest in participation in the program; 160 individuals registered.

On June 24, 2020, members of PDPA, along with several senior administrators at BU, received a very impassioned message from two doctoral students regarding their frustration with BU and the City of Boston in relation to racist behaviors they had experienced personally or witnessed, and the University’s broader responses to racism. Most pertinent in the message was their attention to our “Challenge,” which they felt was trivializing racial equity efforts by framing the work of becoming antiracist using the language of fad diets or social media trends (such as the “Tide-Pod Challenge”), ultimately diminishing the seriousness of the problem. While certainly that was not the intent of the program, the immediate impact that it had led us to pause the 21 Days. This pause would give us time to talk further with these students and reflect on how we could decenter whiteness in the learning we were trying to create, as well as build a resource that would not bring harm to our peers and colleagues of color. Ultimately, the students who had sent the email communicated to us that had the name of the program not been so triggering, it would not have been as problematic for them, and that they did not intend for us to cancel the program, which they felt would be valuable to the BU community. They also communicated their acknowledgement that our program was founded on good intent, with a title modeled on a similar program. After some additional thought and editing of our title and content, we relaunched the program as “21 Days of Unlearning Racism and Learning Antiracism.”

After much self-reflection and conversations as a team, we reached out to those who had registered for participation in the first iteration of the program and the broader BU community, explained our missteps and the actions we had taken to reflect and make changes to the program, and asked them to re-register for the new 21 Days. We had 170 participants register for the second iteration of the 2020 program, which launched on July 6, 2020, and ran through July 26, 2020. All registered participants received daily email reminders for the duration of the 21 Days. These communications included reminders and links to the daily topic, as well as links to additional resources interspersed with reflection prompts.

In addition to the asynchronous content that participants were able to access via the spreadsheet, we also hosted three optional Community Conversations during the 21 Days. The goal of these sessions was to create a space for participants to come together to reflect on their learning and the experience of participating in the 21 Days. A rotating pair of facilitators from PDPA led these conversations. We began each of these conversations by establishing community guidelines for participation in order to create an inclusive and welcoming space for participants. Each conversation was loosely structured to provide space for sharing and reflection, with some pre-planned activities to help guide the conversations. Although many more registered for each event, ultimately, we had small groups of less than 10 participants attend each of the conversations, which we found was a good size for meaningful participation that enabled all the voices present to be heard. Of note, the majority of attendees to the conversations were staff members.

Structural Evaluation and 2021 Remodeling

We did not set targets for engagement or use of the document, nor did we have any expectations for how we wanted those who registered to use the document, as it was difficult to gather data on engagement and evaluate learning in a voluntary program with a diverse set of learners from different populations across the University. Instead, the aim of this work was to create a living resource that would provide structured content for interested learners to engage with however it might be valuable to them. While ideally those who registered to participate would use the curriculum as a starting point towards building the work of unlearning racism and learning antiracism into their daily habits, I also want to acknowledge that many of those who expressed initial interest may well have been engaged in this type of learning elsewhere. However, we do have a few tangible data points worth mentioning.

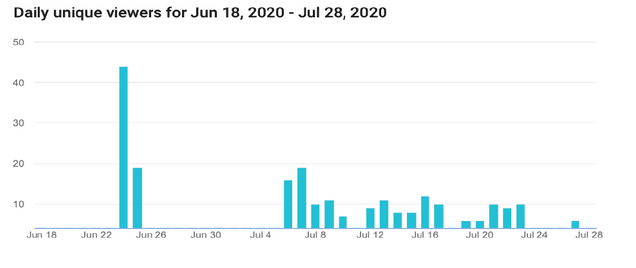

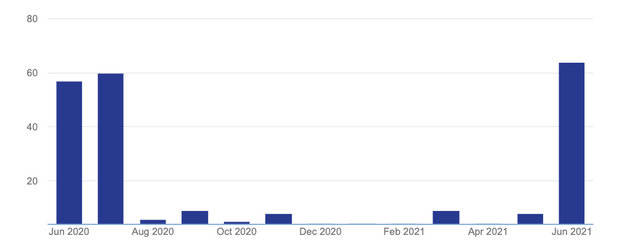

Despite the high registration number for the program, according to Google’s Activity Dashboard, on average only 12 individuals accessed the content daily, with a significantly lower engagement on weekends, and towards the end of the program (see Fig. 2). However, this data only accounts for unique individuals who opened the document on a given day. Therefore, for example, a participant who kept the original spreadsheet open from July 6 to July 26 would not be counted as a unique viewer on days after July 6. My own daily monitoring of the document, which, on most days, showed more than 15 individuals viewing the document, also supports this discrepancy. Such a limitation also accounts for why the Monthly Activity Dashboard shows 60 unique viewers of the document in July 2020 (see Fig. 3).

What figure 3 also shows is an uptick in viewers of the curriculum again in June 2021, when we began to advertise the 2021 iteration of the 21 Days. For the program in 2021, we did not make significant structural changes to the curriculum or program; it was still a 21-day program, with content released five days at a time, and three community conversations scheduled at regular intervals throughout the 21 days. However, we did make changes to the content and daily topics. The first major change sought to make the curriculum more inclusive of non-Black communities of color and intersectional identities, as 2020 had focused on anti-Black racism. Specifically, we added days on the origins and history of Anti-Asian, Anti-Indigenous, and Anti-Latinx racism, as well as four days focused on the intersections of race and gender, sexuality, ableism, and class. The second change was to expand the section on racism in education to add more resources on higher education and academia specifically, as we believed this content would be especially valuable for our audience. To make space for these additional topics, we removed many of the days found in the 2020 curriculum, but because the 2020 spreadsheet remains live, we directed the 2021 participants to the original resource if they were interested in materials on, say, housing segregation.

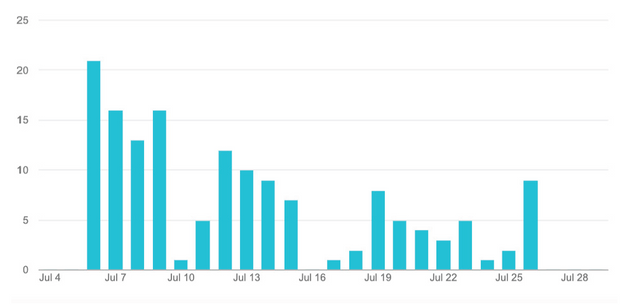

For 2021, we made registration available to faculty and staff from the outset and had 135 individuals register. Significantly, while most registrants in 2020 were doctoral students and postdocs, in 2021, the majority of those registered were staff, with a large reduction in the number of doctoral students and postdocs who registered (see table 2). As Figure 4 shows, the overall engagement in the program reflected similar trends to 2020, with 54 unique viewers of the document in July 2021 compared to the 60 unique viewers in July 2020.

Table 2: Number of individuals registrants in the program by role at Boston University in 2020 and 2021.

| Role at BU | 2020 | 2021 |

| Doctoral Student | 71 | 42 |

| Postdoctoral Researcher | 28 | 2 |

| Faculty | 25 | 28 |

| Staff | 34 | 50 |

| Other student (UG/MA) | 9 | 10 |

Concluding Thoughts

Like any type of change, whether it be individual or structural, unlearning racism and learning antiracism is a long process that takes time. Constructing this curriculum provided the opportunity to build an evolving resource for doctoral students, postdoctoral researchers, and other constituencies at the University. Because it is a digital, open-access document, we can update and revise it over time and share it broadly. We will continue to run the 21 Days program annually and find ways to encourage different populations at Boston University to use the curriculum to suit their own needs. We do not expect every member of Boston University to engage deeply with this material just because we run a program for it. Instead, the hope is that the curriculum can be a tool for change within the broader community, alongside other resources and programs, to be used over time in the service of lasting change.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1646810 (PI Hokanson). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Works Cited

America & Moore. “21 Day Racial Equity Habit Building Challenge,” 2014, https://www.eddiemoorejr.com/21daychallenge

Lally, Phillipa, Cornelia H.M. van Jaarsveld, Henry W.W. Potts, and Jane Wardle. “How Habits are Formed: Modeling Habit Formation in the Real World,” European Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 40, no. 6, 2010, pp: 998-1009.

Appendix – Antiracism and Social Justice Resource/Reading Lists (A non-exhaustive list)

Independent

African American Intellectual History Society, Charleston Syllabus (2016)

African American Policy Forum, A Primer on Intersectionality (2019)

Amy Sanchez, Where do I begin? A 28-day reading plan for white and non-Black POC (2020)

Anna Stamborski, Nikki Zimmermann, Bailie Gregory, Scaffolded Anti-Racist Resources (2020)

Antiracism Project Resources (2020)

Brandi Candoit, Part 1. Unlearning Racism: Anti-Racist and Equity Resources (2020)

Carlissa Johnson, Resources for Accountability and Actions for Black Lives (2020)

Chicago Public Library, Anti-Racist Reading List from Ibram X. Kendi (2020)

Crystal Boson, Get Out Syllabus (2017)

Danah Kowden, Anti-racist starter pack (2020)

David W. Campt, The White Ally Toolkit Workbook (2018)

DIRT, Antiracist Reading List (2020)

Dismantling Racism (Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun), Workbook (2016)

Fractured Atlas, Resources for White People to Learn and Talk about Racism (2018)

Lauren Johnson and Ashley Hodges, Anti-Racist Reading List (2020)

L.Glenise Pike, The Antiracism Starter Kit (2019)

National Museum of African American History & Culture, Talking about Race

Racism Review, Bibliographies about race, racism, and whiteness (2015)

Resource Sharing Project, Anti-Racism Resource Collection (2020)

Sarah Sophie Flicker, Alyssa Klein, Anti-Racism Resources for White People (2020)

Sociologists for Justice, Ferguson Syllabus (2014)

Tatum Dorrell, Matt Herndon, Jourdan Dorrell, Antiracist Allyship Starter Pack (2020)

Tasha K., “Sharable Anti-Racism Resource Guide” (2020)

Tiffany Bowden, Anti-Racism Resource List (2020)

@warmhealer, Anti-racist Action is Essential (2020)

University

Brandeis University, Equity, Inclusion and Diversity, Recommended Readings and Resources (2020)

Case Western University, Anti-Racism Resource List (2020)

Frank Leon Roberts, New York University Black Lives Matter Syllabus (2016)

Harvard University, African and African American Studies Departments, Faculty Reading Recommendations (2020)

Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, The 21-Day Challenge at Heller (2021)

Robert L. Heilbroner Center for Capitalism Studies, The New School, Slavery, Race, Capitalism: A collaborative course and syllabus (2017)

University of California, Davis, Department of English, Anti-Racist Reading Lists (2020)

University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Office of Equity and Inclusion, Antiracism, Diversity & Inclusion Resources (2020)

University of Michigan Library, Autumn Nicole Wetli, An Anti-Racist Reading List (2020)

University of Minnesota, Anti-Racism Reading Lists (2020)

Vanderbilt University, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, Reading and watch list of anti-racism resources (2020)