When the Past is the Classroom

Merging ‘Reacting to the Past’ and Experiential Education

Kathryn Lamontagne, Boston University, College of General Studies

My thanks to the online Reacting Faculty Lounge for introducing me to so many incredible experiential reactors sharing their efforts. Thanks are especially extended to: Jenn Worth, Mark Carnes, Verdis L. Robinson, Kate Jewell, Charlotte Carrington-Farmer, Rebecca Stanton, J.J. Sylvia IV, Leslie Regan, Jace Weaver, Traci Levy, Margaret Tonielli Workman, Brian Klunk, Jason Locke, and John O’Keefe.

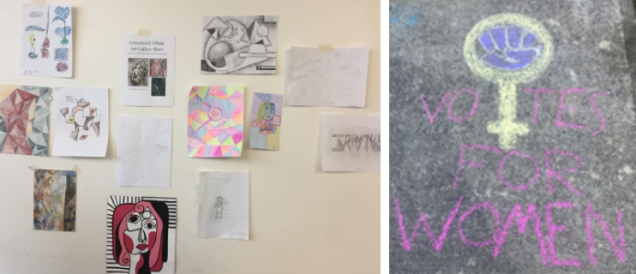

Imagine a classroom where a trumpet–playing student leads a march through the halls of their academic building while playing the “Internationale,” or the class walls are covered with student–created propaganda advocating for women’s suffrage. This same classroom will be the site of weeks of debate, laughter, and dismay as students take part in the gamified role–playing pedagogy of Reacting to the Past (RTTP). Reacting to the Past was developed at Barnard College by Mark Carnes in the late 1990s and has slowly grown in practice to over 400 campuses with a game library spanning hundreds of years and topics (Carnes, Minds on Fire). This pedagogy employs a number of learning styles such as lecture (passive), role–playing (active), creative (active), and speeches (rhetoric) (Berrett). RTTP has become increasingly popular over the past few years and tellingly, in 2020, the American Historical Review published eight reviews of games available via Norton, Reacting’s publisher.

Now, push this dynamic format further and imagine that your students are playing The Threshold of Democracy: Athens in 403 B.C. (2015) while in Athens on a Maymester or semester abroad as was the case for J.J. Sylvia from Fitchburg State University, Massachusetts (Ober et al.) Or, taking part in Frederick Douglass, Slavery, and the Constitution, 1845 (2019) in Rochester, the longtime home of Douglass, as Verdis L. Robinson’s students at Monroe Community College did over a number of semesters (Higbee and Stewart). Charlotte Carrington–Farmer regularly runs The Trial of Anne Hutchinson (2013) at Roger Williams University, taking advantage of its location near Portsmouth, Rhode Island, the town Hutchinson helped found in 1638 (Carnes and Winship). The capacity for student engagement with a historical game, alongside external activities/visits, presents a truly vibrant opportunity for students to master metacognitive knowledge of a topic. Students are forced to confront ideas and primary sources head–on inside and outside of the classroom. Consequently, student buy–in to the game is heightened over the composite experience and correlates to the acquisition of increased summative learning and student retention (Olwell and Stevens; Higbee, The Scholarship of Teaching).

In this paper, I aim to show how RTTP can be further elevated via the use of experiential education outside of the classroom, or reimagined in a virtual world. By this, I mean that active role–playing and learning inside the classroom could be further augmented by on–site (or virtual) visits to spaces relevant to their RTTP game. It may also be the handling of objects or material culture relevant to game play. This kind of whole learning experience effectively immerses the student in the subject matter, creating a level of expertise seldom captured in introductory or general education classrooms. Experiential education “evoke[s] an impression of the ‘whole’ subject to be explored and engage the students in several simultaneous ways” which makes it a natural counterpart, if not synonymous with RTTP (Caine et al. 127). Therefore, a dynamic hybrid experience can be achieved using RTTP with site visits, careful planning, ‘character’ assignments, and creating student buy–in.

I begin by outlining how the pedagogy of RTTP itself works. Then, drawing on my past experience teaching introductory, interdisciplinary general studies/core program courses in the social sciences, but specifically the fields of history and political science, I revisit how myself and others have used experiential education and RTTP successfully within this framework (Lazrus and Kreahling McKay). In doing so, I recount the moments of synergy and synthesis in RTTP and experiential education that create a provocative, active student–centered experience in– and outside of the college classroom.

How does RTTP work?

RTTP uses a number of different platforms to disseminate game play. Each game begins as an idea that is then shepherded through a multi–stage approval and testing process which begins at Barnard where the RTTP Consortium is based. The Editorial and Consortium Boards are comprised of members from universities across North America. RTTP is generally restricted to college students and faculty, but some high schools have participated. There are ongoing changes (2020) to previously established practices regarding institutional memberships for game materials and pay barriers. At the time of this writing, students would generally purchase a game book from Norton and the faculty member at the home institution would access instructor materials/student role sheets directly from the online community/Consortium at Barnard. Faculty could also access a “Faculty Lounge” on social media (namely, Facebook) to share materials, links, etc. Many Faculty Lounge members actively share rubrics, character extensions for larger classrooms, and suggestions to maximize student buy-in by utilizing online platforms Slack or Discord.

Faculty materials are vital for the success of RTTP. Available as PDF documents, these materials include multi–page role sheets, instructions for each classroom period of game play, how game play can be adjusted for class numbers/ length of classes, and additional activities. These additional activities can be as simple as film suggestions, additional primary sources, or most importantly, in–class activities. For example, Mary Jane Treacy developed a number of in–class activities that can be integrated into the larger game, such as instant speeches and a play on ‘Three truths, one lie’ for game play in Greenwich Village, which can be easily recreated in other non–RTTP classrooms. Students are always “in character” and to make sure that others know who their character is and their motivations ‘Three truths, one lie’ (where students make 4 claims about their character and the other students guess which one is the lie) quickly checks comprehension, forces quick rhetorical action, and reinforces the import of intimately knowing character/historical motivations. This is a fast–paced activity that functions similar to an oral quiz, but is also fun and appeals to oral learners. Faculty game materials also contain secret information for the faculty member, or, rather Game Master, to share with select roles. Of note, advice on everything from optimal number of students to course meeting lengths are readily available.

Many “reactors” begin with an introductory micro–game such as Mary Beth Looney’s micro–game “Bomb the Church,” which introduces students to role playing, followed by a few days of building rhetorical confidence (how do I give a speech? connect with my audience?). This is then followed by 2–3 class periods of traditional lecturing on relevant historical, social, and political information and grappling with primary sources (See Fig. 4.). Primary sources are included in all game books, so students generally do not need to purchase additional texts (although this may vary depending on the game). Students would then ‘learn’ their assigned character and begin to make plans with others in their faction. Greenwich Village (GV13) has three factions of labor, suffrage, and indeterminates; but other games, such as Henry VIII, have multiple factions (Treacy, Greenwich Village; Coby, Henry VIII). In most instances the characters are “real” figures but there is an element of fiction to some games. For example, Kelly McFall and Abigail Perkiss, Changing the Game: Title IX, Gender, and College Athletics (2020) is set at a fictional university with fictional characters, but of course the battle over Title IX in the US was very real. This is then followed by actual student–led game play where the major factions battle for the support of the indeterminates. Game play consists of speeches, debates, creating personal influence (termed ‘PIPs’ in RTTP nomenclature) through relationships and the creation of artifacts. Artifacts can include posters, costumes, newspapers, skits, media, music, poetry, articles, and art (See Figs. 1 and 2). Each class day would be dedicated to “Feminist Mass Meeting” for GV13 or, in the French Revolution game a meeting of “The National Assembly” or, sermons in a “Boston Church,” as is the case in the Trial of Anne Hutchinson (Treacy, GV13; Popiel et al.; Carnes and Winship). The student owned gamebook and faculty materials have a timeline of what major actions happen during each class period, which is often the most confusing aspect to newcomers of how to “play” a game without a standard “board.” Students are invited to dress and speak in character to further the role–playing element of the pedagogy. In the past, my own students have taken this segment of the pedagogy the furthest and become character actors, changing into a wig or certain tie before class to fully engage in their role.

The game is played in the classroom, but also in the dorms, and over the internet, creating an all–encompassing learning environment. Most importantly, the students conduct the class and the instructor becomes the observer, flipping the classroom and the implications of how information is mediated and experienced. During the Pandemic of 2020, the use of Slack and Discord as ex cathedra settings for debates and discussions has been especially robust. There is a dynamism in the Reacting classroom that is seldom found in a traditional lecture or discussion classroom as the issues of yesterday become the debates of today (Carnes, Minds on Fire 1–16). Critical thinking, creating arguments, responding quickly to constituent concerns, and objectivity are all skills that are intuitively embraced in the RTTP class (Galbraith).

Experiential Education

When the already dynamic RTTP experience tumbles out of the classroom, we see a complete immersion in the historical topic, rarely accomplished in the traditional classroom via PowerPoint, discussion sessions, or a textbook. History is mediated by the primary sources – and, combining RTTP and the ‘primary source’ of a space/artifact is theoretically invigorating. Primary sources, whether they be the written word or a material object (building, painting, etc.) are the building blocks of unpacking the historical narrative. Consequently, the more varied the sources a student can access to engage with this narrative, the greater their level of achieving mastery. To borrow from Pierre Nora, through experiential education the participants are engaging with (re)locating “lieux de mémoire” or, sites of memory, and imbuing them with further layers of meaning. This is not historical reenactment, but historical exploration that is accomplished by plumbing the emotional depths of real people. Students are not meant to copy what was done, but via careful analysis consider the ‘maybes,’ ‘what could have beens,’ frustrations, and tensions that they themselves experience in their roles. To push the construct to its furthest, bringing the students into the space, lieux de mémoire itself, creates the opportunity for the highest level of coherence and historical, rhetorical understanding. By doing so, the experiential inside and outside of the classroom goes beyond game play into serious theoretical and pedagogical work.

Consider again the student who has played or is playing Greenwich Village, 1913 as did Kate Jewell’s students at Fitchburg State in 2018, which was then followed by a visit to Greenwich Village led by Columbia University’s Rebecca Stanton. Jewell’s students spent class time in their imagined space of ‘Polly’s,’ a hangout for the bohemian set in Greenwich Village on MacDougal Street, and then visited the historic Polly’s (the building is still there and owned by New York University) and a contemporary bohemian hangout, La Lanterna di Vittorio. They also visited the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and Washington Square Arch. Jewell’s student, Kaitlynn Chase, currently a Master’s candidate in English at Clark University, recalled the power of this experience in the actual Greenwich Village as seminal, as it allowed her and her classmates in the Honors program to “completely connect to the [realness of] the people” in GV13 and “helped put that into perspective.” In addition to visiting GV13 sites of memory, Jewell’s students had also played Jason Locke’s Vice in New York, 1895 (unpub.) and found the connection between the two games based in the city incredibly enlightening. The students then visited the Merchant House Museum and the Tenement Museum in New York City. Chase felt visiting the Merchant House was “amazing” and made the game more “tangible.” Jewell echoed this idea and felt that the RTTP classroom–based pedagogy underpinned with post–game experiential visits was integral to her class not just learning the historic materials but internalizing them, “one student even became a history major,” after the course. Additionally, most of the students had never been to New York City and physically seeing the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and the Washington Square Arch were moments of synergy between reading and really experiencing the past. It is easier to “react to the past” when you can physically walk the streets of New York City or Paterson, New Jersey where these events changed history (Treacy, Paterson).

Students do not need to necessarily travel far to take part in experiential education. New York, Verdis L. Robinson’s Douglass students from a Rochester Community College dined at Delmonico’s in the same city, where John C. Calhoun advocated for slavery in abolitionist Rochester as part of the Frederick Douglass game. My own students felt the power of the past when they walked the streets of nearby downtown New Bedford, Massachusetts where Douglass fled after escaping slavery. One student reflected after our course,

Standing in front of the Nathan and Polly Johnson house with the Park Ranger, a house that was a stop on the Underground Railroad that Douglass lived in was surreal in many ways. I felt so connected to this man that lived 100 years ago instantly and it made it more real than in class, but class already felt really real too!

This kind of powerful use of the historic space creates an opportunity for students to experience their character, the game topic, and themselves across multiple domains. Further, it illustrates that experiential education does not require a flight, major expense, or hours–long drive, which are incredibly important in a world that has now experienced full–scale online learning. Stanton, based in New York City, regularly takes student to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to access Ancient Greek or Chinese artifacts (Athens 403 BC, Confucianism and the Succession Crisis of the Wanli Emperor) and the City Museum of New York for changing exhibits related to games, which can also be visited virtually (Ober et al; Gardner and Carnes). Leslie Regan from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign enthusiastically uses on–campus museums such as the Krannert Art Museum for students to view John Sloan prints, a character in GV13, or women in sport (Changing the Game). As mentioned earlier, Carrington–Farmer (Anne Hutchinson) brings her students to spaces throughout the capital and East Bay of Rhode Island that Hutchinson shared with Roger Williams, her university’s namesake. She also makes great use of free tours from the National Parks Service and long–time relationships with rangers, such as John McNiff in Providence. Carrington–Farmer has used an exhaustive number of experiential activities in tandem with the Hutchinson game including visits to Danvers and Salem, Massachusetts and London. Traci Levi, from Adelphi University, just outside of New York City, brought her Constitutional Convention/GV13 students to the Tenement Museum as well (Coby, Constitutional Convention; Treacy, GV13).

As part of the learning outcomes for my introductory interdisciplinary political science and history course at Roger Williams University, the university required that I organize ‘events’ – one on–campus and one ‘field trip’ – for my class. This provided me with an opportunity to teach a hybridized model that ran the gamut from traditional lecture to experiential education to interactive game play via RTTP. It became apparent over two semesters that the hybrid model was extremely successful in that it greatly increased student buy-in to a required general education class for non-majors, helped develop strong relationships between first-year students which improves overall retention, and was, most importantly, fun. The dynamism of the hybrid model succeeds because it brings together trips and game play – active learning is, by its very nature, fun. The opportunity to have ‘fun’ while learning is the hallmark of experiential education, as stated earlier it correlates directly to the acquisition of increased summative learning. The success of the model can be measured in student feedback surveys with comments ranging from, “I had no idea history didn’t need to be boring, it was fun,” “I never talked in class before this one, it is actually fun to be involved and it makes class go by really fast,” “I’m a math and engineering person and don’t really like arguing and politics but this was fun and I got to role play,” and “playing a game in class and going places and doing stuff together was really fun. I liked making stuff too like TikToks and posters. I felt like I was procrastinating because I was doing fun stuff, but it was class work!” The common denominator here is “fun” and the power of the promise of fun significantly increases student buy-in for the game.

For our on–campus event, I worked closely with Michelle Farias, archivist at the Redwood Library and Athenaeum in Newport, to curate a collection of primary and secondary sources for my students to examine before beginning game play (See Fig. 3). Farias graciously came to campus and gave a mini–presentation on the incredibly wide–ranging sources from the Redwood collection that fit into our game, but also the course itself. She brought suffrage texts belonging to Gilded Age bon vivant Alva (Vanderbilt) Belmont, bound issues The Masses (ed. Max Eastman, a character in GV13 and featured prominently in the game), but also anti–suffrage texts written by women, which shocked the students as they had not realized that any woman might be against the right to vote for herself (Goodwin, Anti–Suffrage). For many first–year students this was their first time physically handling primary sources (but, also handling materials over 50 years old). Most reported previous primary sources were only viewed online and included explanatory blurbs. In this case, students 1.) interacted with an archivist and confronted the import of historical repositories 2.) learned how to handle delicate materials 3.) considered the value of provenance (i.e. who was Alva Belmont? Why do I care that she owned this particular book?) and, 4.) saw how primary sources can be integrated into real life scenarios and used as tools to support arguments. Here, it is evident that experiential education is not necessarily leaving one space to travel to another (which often privileges the able–bodied or others) – it can be in as simple as looking at common objects in a very different way in one’s home or an after–hours classroom space.

Some pedagogical examples for RTTP which bridge the gap between a traditional active, off–site experiential aspect and a more physically passive experience are using films, and in our current pandemic world virtual visits to museums, galleries, and archives. I have had a great amount of success by holding after–hours movie and pizza nights that I use to show clips from Labor films, suffrage and labor rallies, Traffic in Souls (1913) and even Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936). Viewing these sources during game play, but outside of the gaming classroom, furthers the pedagogical reach by adding an additional layer of immersion in the topic. Carrington–Farmer, as part of the Anne Hutchinson game, has run a ‘Writing with a Quill Workshop’ to tap into the quotidian as part of understanding the lives of the game characters. Others have been successful in using their own athletic staff and players to discuss the effects of Title IX on their campus. Over the pandemic crisis of the 2020 Spring semester, many professors have brought RTTP online and created new types of “experiential visits” to add to their games – virtually visiting museums such as the Musée D’Orsay in Paris or the Guggenheim in New York City. Consequently, while it may seem that experiential education dictates a physical visit, it is evident that value and experience can be achieved wherever the opportunity for engagement presents itself. Student immersion in the topic is the key aspect in combining the experiential and the game itself.

In closing, Reacting to the Past is an innovative and engaging pedagogical format that stretches the classroom in many ways. Augmenting RTTP with immersive experiential education of any kind outside of the physical classroom space, whether it be study abroad, local visits, the archives, workshops, films, or in the virtual world, offers a heightened environment for the acquisition of summative knowledge for university students. Further, the students and the faculty member have fun while creating stronger interpersonal relationships with each other, which also benefits the university in terms of student retention. Most importantly, the dynamic combination of RTTP and the experiential, offers general education students in introductory level classes the opportunity to master historical and rhetorical understanding of a topic in an innovative, inspiring way.

Fig. 4.(below) Example class schedule for Greenwich Village, 1913 (90 mi- nute blocks) and experiential visits

| RTTP Overview | Archival visit to view The Masses and other sources |

| Looney’s “Bomb the Church” | Students exposed to the RTTP methodology |

| Lily Lamboy and methods of Rhetoric videos | Students exposed to public speaking |

| Session 1: Women’s Rights and Suffrage | Overview of issues in traditional lecture format, primary sources integrated |

| Session 2: Labor and Labor Movements | Overview of issues in traditional lecture format, primary sources integrated |

| Session 3: The Spirit of the New (Traditional Lecture with Activity) | Overview of issues in traditional lecture format, primary sources integrated. Session begins with considering modern art actively |

| Assign Roles and students get to know each other in role | Meet with students privately and in factions to discuss role sheets, ideas, goals. |

|

Session 4: The Suffrage Cause |

Suffrage leaders argue their cause. This session takes place at Polly’s, a restaurant, and works when catered with light snacks. |

|

Session 5: Labor Has Its Day |

Labor leaders argue their cause. Film and Pizza Evening |

|

Session 6: The First Feminist Mass Meeting |

Indeterminate and Wild Card students engage with ideas of Labor and Suffrage more carefully. Present own ideas. |

|

Session 7: An Evening with Mabel Dodge |

Another session that benefits from music or food. Those who have stood out in game play are asked to speak. |

|

Session 8: Thus |

Final arguments and game vote, presentation of student writing and art in character. |

|

Session 9: 1917— Facing the War and Debriefing the Game |

What really happened? |

|

Additional Experiential: |

Visit to Greenwich Village, Paterson, NJ, Provincetown, or Washington, D.C. |

Works Cited

Berrett, Dan. “How ‘Flipping’ the Classroom Can Improve the Traditional Lecture.” Chronicle of Higher Education, February 19, 2012.

Caine, Renate Nummela, et al. 12 Brain/Mind Learning Principles in Actions: The Fieldbook For Making Connections, Teaching, and the Human Brain. Corwin, 2005, p.127.

Carnes, Mark C. Minds on Fire: How Role–Immersion Games Transform College. Harvard University, 2014.

Carnes, Mark C. and Michael P. Winship. The Trial of Anne Hutchinson: Liberty, Law, and Intolerance in Puritan New England. Norton, 2013.

Carrington–Farmer, Charlotte. Interview with the author. January 10, 2020.

Chase, Kaitlynn. Phone interview by author. January 29, 2020.

Coby, J. Patrick. The Constitutional Convention of 1787: Constructing the American Republic. Norton, 2017. Coby, J. Patrick. Henry VIII and the Reformation Parliament. Norton, 2013.

Galbraith, Gretchen. “‘I had almost forgotten I was in a classroom setting’: Reacting to the Past and Engagement with Historical Thinking.” The Role of Agency and Memory in Historical Understanding: Revolution, Reform, and Rebellion, edited by Gordon Andrews and Yosay Wagdi, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017, pp. 377–39.

Gardner, Daniel K. and Mark C. Carnes. Confucianism and the Succession Crisis of the Wanli Emperor, 1587. Norton, 2014.

Goodwin, Grace Duffield. Anti–Suffrage: Ten Good Reasons. Duffield and Company, 1915.

Higbee, Mark and James Brewer Stewart. Frederick Douglass, Slavery, and the Constitution, 1845. Norton, 2019.

Higbee, Mark D. “How Reacting to the Past Games ‘Made Me Want to Come to Class and Learn’: An Assessment of the Reacting Pedagogy at EMU, 2007–2008.” The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning at EMU, 2:4, 2008, http:// commons.emich.edu/sotl/vol2/iss1/4

Jewell, Katherine Rye. Phone interview by author. January 24, 2020.

Lazrus, Paula Kay and Gretchen Kreahling McKay. “21: The Reacting to the Past Pedagogy and Engaging the First‐year Student.” To Improve the Academy 32:1, 2013, pp. 351–63.

Lazrus, Paula Kay. Building the Italian Renaissance: Brunelleschi’s Dome and the Florence Cathedral. University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Locke, Jason. Riis, Roosevelt, and the Reformers: Policing Vice in New York, 1895. unpub.

Looney, Mary Beth. “Bomb the Church,” 2017, Accessed March 20, 2020. URL: http:/ arthistoryteachingresources.org/2017/11/bomb–the–church/.

McFall, Kelly and Abigail Perkiss. Changing the Game: Title IX, Gender, and College Athletics. Norton, 2020.

McKay, Gretchen K. et al. Modernism versus Traditionalism: Art in Paris, 1888–89. University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux De Mémoire.” Representations, no. 26, 1989, pp. 7–24.

Ober, Josiah, et al. The Threshold of Democracy: Athens in 403 B.C. Norton, 2015.

Olwell, Russell and A. Stevens. “‘I had to double check my thoughts’: How the Reacting to the Past Methodology Impacts First–Year College Student Engagement, Retention, and Historical Thinking.” The History Teacher, 48:3, 2015, pp. 561–572.

Popiel, Jennifer et al. Rousseau, Burke, and Revolution in France, 1791. Norton, 2015.

“Reacting to the Past Consortium, Barnard College,” 2020, Date of access: March 5, 2020. https://reacting.barnard.edu/consortium.

“Reviews of Role–Playing Classroom Games: Reacting to the Past.” The American Historical Review, 125:1, February 2020, pp. 146–159.

Treacy, Mary Jane. Greenwich Village, 1913: Suffrage, Labor, and the New Woman. Norton, 2015. Treacy, Mary Jane. Paterson 1913: The Silk Strike. unpub.