Re-“Making” General Education

Envisioning Gen Ed as a Digital Humanities Makerspace

Kristin Novotny, Ph.D. and Katheryn D. Wright, Ph.D.

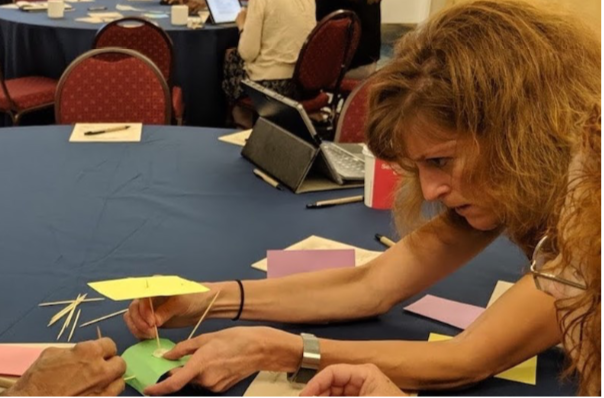

Dateline: Orlando, Florida. I’d brought index cards, toothpicks, and a roll of masking tape, but the icebreaker activity was my colleague’s idea. “I participated in a great experiential exercise in my Wearable Computing course at the DHSI Sum- mer Institute,” Katheryn had said. “Maybe we should try it?”

So after discussing the activity — originally designed by Jessica Rajko — it came to pass that we began a presentation about the power of Digital Humanities at the Association for General & Liberal Studies (AGLS) 2019 annual conference by giving attendees 20 minutes to build the tallest free–standing structures they could. What could possibly be the connection between toothpick towers, Digital Humanities, and the future of General Education? It turns out that it’s all about the power of “making.”

Each year, AGLS hosts a conference where scholars and teachers in a variety of fields gather to interrogate general education, and learn about different approaches to liberal learning in a variety of academic contexts. We are interested in exploring how Digital Humanities and maker pedagogies can inform the theory and practice of general education.

Learning By Making. Unlike many icebreaker activities, our workshop built planning time into the process. Three groups of 3–4 people sat looking at their small piles of materials, forbidden to touch them for the first 10 minutes. “One person will take notes about the process and observe the interaction,” we instructed them. “The note–taker can’t touch the materials, but can help the group talk through the process.” After 10 minutes of planning, the teams were given 10 minutes to build. When we announced it was time to build, the teams plunged into the task of constructing the towers.

Meanwhile, we circulated the room as participants deliberated the key components of a successful edifice. We watched as they judged how their sparse materials could be configured to optimize stability, lightness, height. One team stood the index cards on their long ends, cross–hatching them for maximal stability. Another team curved the cards into paper arcs. The final team made more of a stacked–tables structure, with toothpicks for legs. There was a lot of trial and error, a lot of laughter and frustration. Ten minutes flew by.

The Power of Debriefing

Next came arguably the most important part of the activity: the debrief. The entire group migrated from table to table as team participants talked through their process. They admired each others’ handiwork, laughed and puzzled over their failures, making mental notes for “next time.”

We focused the debrief on two broad categories of questions: (1) to what extent was your team’s activity process- based, iterative, and inquiry-based? Did it focus on how to do what you did, on the sequencing? To what extent did you make adjustments and refine your ideas? How did question–asking move the process forward? (2) To what ex- tent was your team’s activity collaborative and interdisciplinary? Did you utilize different disciplinary and temperamental strengths, and if so, how? How did you decide who would take on which roles? What was the give–and–take of your interaction?

These structural and procedural questions were designed to illuminate a larger point: the tower–building exercise is an (admittedly low–tech) approximation of “Maker Pedagogy” (Bullock 2014). We define the concept of maker pedagogy below, tracing its relationship to and potential for the Digital Humanities. In our workshop, as in one recent analysis of feminist maker pedagogy, the “process of building is not a means to an end, but a metaphor for engaging theory” (Cipolla 2019, 272).

At the surface level, those who attended our AGLS workshop invested in the icebreaker activity because it was fun, hands–on, and posed an intellectual problem that seemed tantalizingly simple to solve. At a deeper level, the takeaway was the power of “making:” a key component in the practice of Digital Humanities that, we argue here, holds great potential to re–invigorate Gen Ed.

Making, Education, and Maker Pedagogy

In a cultural era of DIY craft beer, paint–and–sip parties, and Etsy pages, the concept of “making” is very on–brand. “Makerspaces” like this are popping up with increasing regularity in communities and on college campuses. According to John Spencer, a makerspace is “simply a space designed and dedicated to hands–on creativity” (Gonzalez 2018). Sheridan et al (2014) note that makerspaces “value the process involved in making — in tinkering, in figuring things out, in playing with materials and tools” (528). The process of making can be both generative and educative; it is tinquiry, in Mann’s words: “tinkering as inquiry” (29).

Making is a powerful form of experiential education. Spencer argues that “[students] need to be able to engage in iterative thinking, creative thinking, critical thinking, they need to know how to pivot, how to change, how to revise, how to persevere. They need to solve complex problems. They need to think divergently. All of those are involved in that maker mindset” (Gonzalez 2018).

Indeed, because learning “is deeply embedded in the experience of making” (Sheridan et al, 528), it is important to bring attention to the practice of “Maker Pedagogy.” We define Maker Pedagogy as the process of iterating ideas and plans in an interdisciplinary, collaborative educational space, with the intention of producing something concrete. What is produced could be a project, activity, paper, plan, theory, idea, or object. In addition: “This mode of teaching privileges activities that are interdisciplinary, immersive, integrative, multi–age, project–based, and collaborative. Maker Pedagogy entails that students are active, moving and Making, not memorizing” (Novotny 2019, 46).

Making is not only interactive; at its best it is an inclusive practice, driven by self–determination and authenticity (Mann 32). According to Byrne and Davidson, making erases or transcends disciplinary boundaries (2015, 11). Similarly, Sheri- dan and colleagues find that “[D]isciplinary boundaries are inauthentic to makerspace practice … Makerspaces seem to break down disciplinary boundaries in ways that facilitate process– and product–oriented practices, leading to innovative work with a range of tools, materials, and processes (2014, p. 527).

Making is not inevitably inclusive or barrier–breaking, however. While the maker movement has the potential to create “Maktivists” — creators “who make things for social change” (Mann 29) — educators like Cipolla warn that the main- stream maker movement valorizes market values and is deeply marked by gender, race and class distinctions (266–267). Identifying as a maker, argues Chachra, is “a way of accruing to oneself the gendered, capitalist benefits of being a per- son who makes products” (Chachra, 2015).

To oppose this, some authors believe we must practice critical making “as a form of intervention in hierarchical power systems,” one that pays attention to the relationship between the maker and what is made, and centers the process of collective making rather than finished products (Cipolla, 266). Similarly, Novotny has argued that Maker Pedagogy can democratize the pursuit of knowledge due to its “potential to unmoor implicit boundaries in one’s academic practice … [and] to broaden and complicate epistemological beliefs (how knowledge gets created, by whom, for whom).” It thereby invokes “an interesting, possibly disruptive set of power dynamics.” (Novotny 2019, 56–57).

Maker Pedagogy and Digital Humanities: A Possible Model for Gen Ed?

To define Digital Humanities simply, it (1) uses digital tools to interrogate questions important to the liberal arts and humanities, and (2) examines the contexts of digital and new media technologies. Digital Humanities, with its myriad methodological and interdisciplinary approach- es, is a particularly good example of making that facilitates tinquiry and intellectual play.

Interestingly, Franzini (2016) defines DH not as a field but as

the digital alter ego of intercultural studies: a community bridge or a space where people from different disciples and backgrounds come together to learn how to talk to each other and to effectively combine skills to conduct joint and interdisciplinary research.

She thus sees DH as a digital forum for interpreting and negotiating meaning, skills that are vital to liberal education. Digital tools have a unique potential to help us frame and understand places — both in the past and present — from a variety of perspectives and contexts.

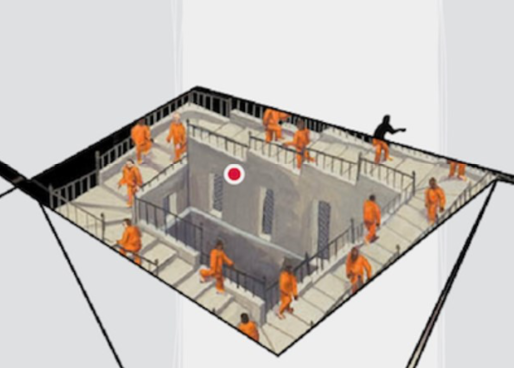

An excellent example of a DH approach that works in this way is The Knotted Line (see image below). According to its website,

The Knotted Line is an interactive, tactile laboratory for exploring the historical relationship between freedom and confinement in the geographic area of the United States. With miniature paintings of over 50 historical moments from 1495-2025, The Knotted Line asks: how is freedom measured?

The Knotted Line combines disorienting audio (that can be turned off) with a purposefully non–linear and, fittingly, knotty presentation format. The site enables users to uncover historical examples in the United States where human freedom has been subverted. In doing so, users move down a twisty, sinuous timeline where they use their mouse or trackpad to coax information/events to reveal themselves. Sometimes a glimpse reveals itself momentarily and then moves away, forcing the user to hunt for the elusive information. It’s a powerful visual metaphor for the deliberately disguised nature of the carceral state.

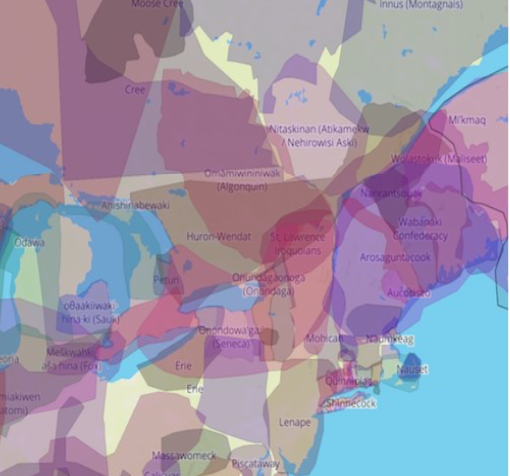

Another terrific example of the ways in which hidden and contested meanings are digitally revealed is the Native Land website (see image below). Here the simple map — often assumed to be factual and value–free — is revealed to contain multiple layers of power, culture, and history.

Native Land is a tool that maps out Indigenous territories, treaties, and languages. …This tool is not meant to be an official, legal, or archival resource. It is instead a broadly researched and crowdsourced body of information. It is meant to encourage education and engagement on topics of Indigenous land—particularly, where you are located. Native Land brings about discussions of colonization, land rights, language, and Indigenous history tied to our personal histories. We hope this guide makes you, the reader, want to know about the land you live on.

Digital Humanities projects are thus particularly adept at promoting immersive “place–based learning” that examines connections between local environments and broader conversations about specific concepts, inquiries, and/or theories. This can even be true in the context of commercial video gaming (see image below).

Walden, A Game is an exploratory narrative and open world simulation of the life of American philosopher Henry David Thoreau during this experiment in self-reliant living at Walden Pond. The game begins in the summer of 1845 when Thoreau moved to the Pond and built his cabin there. Players follow in his footsteps, surviving in the woods by finding food and fuel and maintaining their shelter and clothing. At the same time, players are surrounded by the beauty of the woods and the Pond, which holds a promise of a sublime life beyond these basic needs. The game follows the loose narrative of Thoreau’s first year in the woods, with each season holding its own challenges for survival and possibilities for inspiration.

As educators in a Core liberal studies program, we believe strongly in the possibilities of Digital Humanities to promote project–and–place–based, interdisciplinary academic work — so much so that we spent hundreds of hours constructing Bodies: A Digital Companion for our own courses.

Bodies: A Digital Companion is an online, interactive course text created on the free, open–source Scalar publishing plat- form. Prior to its creation, instructors in the sophomore–level “Bodies” course at our college switched amongst existing Bodies textbooks that did not precisely meet the needs of our students. While the idea for a new text was first envisioned as a printed reader, the digital text that resulted combines well–known academic writing about embodiment, new essays written by Bodies instructors about shared key concepts, and relevant media artifacts. The text is not only free and inter- active, designed for born–digital students, but is highly amenable to modification with new materials and themes.

Circling Back, Looking Forward

The preceding examples of Digital Humanities work stand in stark contrast to older, more traditional disciplinary models of undergraduate education. We are all too mindful that Liberal/General Education often manifests itself in rigid, standardized curricula and “pick one from each column” requirements. Indeed, in a 2015 survey reported by AAC&U, a full three quarters of all U.S. colleges relied on distribution requirements (Jaschik 2016). We believe, however, that the Digital Humanities provides a possible remedy, a way to break out of the ‘checklist’ approach to liberal learning and offer a compelling alternative.

Participants in the AGLS workshop that began this article helped us to crowdsource preliminary responses to the question of “how can DH inform and transform Liberal/Gen Ed?” In thinking through the places where DH, maker pedagogy, and Liberal/Gen Ed intersect, one participant told us that “the maker mindset is the Gen Ed mindset.” They further suggested that learning how to navigate complex webs of information is vital to both DH and Gen Ed, particularly as new forms of media become increasingly important. In a world in which policy matters are decided by Tweets, the ethics of the digital space becomes a crucial area of focus.

Our workshop participants also noted that the academic questions that matter most will be best answered in a multi– disciplinary space. DH projects and methods can be used to encourage interdisciplinary collaboration among faculty in more traditional, distributive menu–based programs. This can open doors to further collaboration, and potentially help collapse traditional silos. Regardless of how far down a DH path schools prefer to go, DH projects like Native Land and The Knotted Line can be used immediately to engage students in discussions of equity and inclusion.

Here are other potential areas of opportunity to consider when implementing Digital Humanities:

- Embedded in a first year experience

- Course design

- Professional development

- Specific units

- Shared components across multiple sections of the same course

- Co–curricular opportunities

- Program outcomes

- Center/Institute/Research Hub

- Mission/Vision/Values

Overall, we are excited about the iterative, design–thinking practices of DH, and want to think more deeply about how the process that occurs in dedicated makerspaces can also happen in the context of Liberal/General education. U.S. academic structures are only beginning to consider what Digital Humanities and Liberal/Gen Ed could look like when mixed together. Let us dare to re–imagine, through interdisciplinary making practices, what Liberal/Gen Ed could be.

Works Cited

Bullock, S. “What is maker pedagogy?” (2015, May 24). Retrieved from http://makerpedagogy.org/en/what–is–maker–pedagogy–some–early–thoughts/

Byrne, D., & Davidson, C. (2015, June). MakeSchools Higher Education Alliance State of Making Report. Retrieved from http://make.xsead.cmu.edu/week_of_making/report

Chachra, D. “Why I Am Not A Maker.” The Atlantic. (2015, January 23). Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/ technology/archive/2015/01/why–i–am–not–amaker/384767/

Cipolla, Cyd. “Build It Better: Tinkering in Feminist Maker Pedagogy.” Women’s Studies Volume 48, Issue 3 (2019), pp. 261–282.

Franzini, Greta. “Digital Humanities.” YouTube (2016). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l1XG7AXVJPE Gonzalez, J. “What Is The Point of a Makerspace?” Cult of Pedagogy. (2018, May 20). Retrieved from https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/makerspace/

Jaschik, S. “Distribution Plus: Survey of Colleges Finds That Distribution Requirements

Remain Popular but with New Features.” Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/01/19/survey–colleges–finds–distribution–requirements–remain–popular–new–features. Accessed 1 Apr. 2019.

Mann, Steve. “Maktivism: Authentic Making for Technology in the Service of Humanity.” DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media. Eds Matt Ratto and Megan Boler. MIT Press, 2014, pp. 29–51.

Native Land. The Land You Live On: An Education Guide (2019). https://native–land.ca/wp/wp–content/uploads/2019/03/teacher_guide_2019_final.pdf

Novotny, Kristin. “Maker’s Mind: Interdisciplinarity, Epistemology, and Collaborative Pedagogy.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education Volume 8, Issue 1 (2019), pp. 45–62 https://ojed.org/jise

Sheridan, K.M., Halverson, E.R., Litts, B.K., Brahms, L., Jacobs–Priebe, L., and Owens, T. (2014). “Learning in the Mak- ing: A Comparative Case Study of Three Makerspaces.” Harvard Educational Review, 84(4), 505–532.

Wright, Katheryn and Kristin Novotny, eds. Bodies A Digital Companion. Common text for COR 240: Bodies, 2017. http://scalar.usc.edu/works/bodies/index