Measuring Expressions of Reciprocity in Institutional Resources of Service Learning

Charisse S. Iglesias, University of Arizona

As a fairly new service learning (SL) practitioner, I did what any inexperienced educator might do and went online to find resources on best practices. I knew that SL needed to be critically examined and implemented and was an “ethically tenuous territory” in which my students would struggle to explore (Jagla 74). I am not exempt from sometimes floundering in the “ethically tenuous territory” through my own community partnerships, especially as I am currently delving into my first, fully developed SL project partnering my first-year composition class and an eighth grade class. My community partner and I have made strides to incorporate best practices of SL since we first started our partnership a year ago. Cultivating reciprocal partnerships requires a lot of trial and error and acceptance of the limitations of myself and my community partnerships, which propels this study on examining expressions of reciprocity in SL resources: how can SL practitioners hope to improve upon their community partnerships if they are not properly trained to do so? As an advocate for SL practitioners, especially inexperienced ones, I am driven to continue finding ways to improve SL resources for both university and community partners. This study gives a booming voice to the silenced community partners that are not being consistently framed as co-creators of knowledge in a co-intentional education.

My search for best practices was disappointing, yet fruitful. The resources I had come upon from my online search were inconsistent, being both vague yet too prescriptive. My bewilderment of SL practice fostered my drive to study the resources, specifically SL handbooks, for their expressions of reciprocity and how they might contribute to disjointed implementation in the classroom. SL handbooks are lengthy documents that are locally authored and institution-backed, and are how-to manuals on SL development. They range from 15-70 pages and describe best practices, complete with vignettes and sample lesson plans. SL handbooks boast proficiency; however, the practice is still problematic by often positioning university partners as the knowledge givers, and community partners as knowledge receivers (d’Arlach et al. 6). Consequently, dangerous power imbalances manifest when community voice is marginalized, not prioritized (Flower and Heath 43), suggesting that current SL design is problematic, and functions as obstacles to community voice by failing to cultivate self-awareness and critical consciousness. Analyzing SL handbooks for their expressions of reciprocity informs the practice of implementing reciprocity in SL classrooms. This study holds resources accountable for modeling appropriate and robust strategies for the SL practitioner.

Considering that SL handbooks may be the only resource instructors use to design, the purpose of this small corpus study is to examine how reciprocity is expressed in SL handbooks. The theoretical framework that informs this study is Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy, which suggests politics and education are intertwined, and “co-intentional education” frames the relationship between university and community partners as co-creators of knowledge (69).

What Does Reciprocity Look Like?

Reciprocity, where partners share “authority in and responsibility for knowledge creation,” is a major tenet in SL pedagogy (Harrison & Clayton 31). However, expressions of reciprocity vary in SL classrooms, suggesting that expressions of reciprocity also vary in the resources made for SL design (Dostilio et al. 18).

SL research has demonstrated reciprocity in a variety of ways. Rosenberg argues that an integral part of building reciprocal partnerships is engaging difficulty (66). The power relations between university and community partners are “fluid, unstable, and constantly changing” (Rosenberg 66). Therefore, we must be mindful of our roles as SL practitioners and explicitly guide stakeholders by shifting and redefining our methods to further cultivate meaningful partnerships.

Furthermore, in their reflective essay on community writing and sustainability, Cella et al. argue that “relationships must come before projects” (41). Additionally, Cushman advocates for SL initiatives that actively involve the researcher and instructor by conducting informal interviews with the community to ensure that goals are consistent with the community’s, and by regular interactions between undergraduates and community youths (43). The need for a “consistent, reliable presence of university representatives” in the community was paramount to the quality of the interactions and future projects (Cushman 57).

Furthermore, d’Arlach et al. studies the “recipients of service” through qualitative interviews with nine community members who participated in a mutual language exchange program (5). Results showed “cliquey” behavior by university partners suggested to community members that the university partners did not take the program seriously and participated merely because it was required (13). However, community partners found the reflective practices about the “cliquey” behavior empowering and humanizing, providing them a voice of influence. This form of reflection and strategies described above helps to ensure community voice and reciprocity by making sure the community partners do not undergo an experience through SL that resembles a “hit and run” (Bickford & Reynolds 234).

Measuring Reciprocity in Service Learning Handbooks

The eight SL handbooks in this study are PDFs, open access, and from four different types of institutions: Community Colleges (CC), Private Research Universities (PRR), Private Liberal Arts Colleges (PRLA), and Public Research Universities (PUR) (see Table 1). This corpus was a convenience sample of the first SL handbook that appeared from a Google search of “Community College Service Learning Handbook,” and so on. I chose to find two SL handbooks from four different types of institutions for greater variety, and all are from the continental US. Reflecting back on the narrative that began this essay, the convenience sample models the process that inexperienced SL practitioners would use to find open access resources online.

Using Ant Conc, an open access concordance program, I converted all eight SL handbooks into TXT files and used Ant Conc to measure expressions of reciprocity by locating:

- Word occurrences of “Reciproc*” and “Community Partner*”

- Reflection practices that problematize the relationship between university and community partners

- Explicit sections that promote reciprocity

I conducted a critical discourse analysis of the small corpus to locate reciprocity expressed in three different ways as explained above. Critical discourse analysis of a small corpus, using the critical pedagogy framework, unveils the inconsistencies and injustices about language on a wider scale (Wodak and Meyer 157), which best serves this study’s purpose of locating the discrepancies of expressions of reciprocity, an agent of cultivating co-creating partnerships.

Words that Describe Reciprocal Partnerships

The table below shows the instances of “reciproc*” and “community partner*,” which is not an exhaustive list of words that determine if reciprocal partnerships are achieved. However, the instances of those words and their variations (e.g. reciprocity, reciprocal, community partner, community partnership(s), community partnering, etc.) help determine the overall tone of each handbook. If, for example, “reciproc*” occurs two times in one handbook and 10 times in another, the handbook that has 10 instances is more likely to express it thoroughly.

Table 1: Key of Institution Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Institution | Abbreviation | Institution |

| CC1 | Community College | PRLA1 | Private Liberal Arts |

| CC2 | Community College | PRLA2 | Private Liberal Arts |

| PRR1 | Private Research | PUR1 | Public Research University |

| PRR2 | Private Research University 2 | PUR2 | Public Research University 2 |

Table 2: Occurrences of Words that Describe Reciprocal Partnerships

| Institution | #Pages/#Words | Instances of “Reciproc*” | % of “Reciproc*” | Instances of “Community Partner*” | % of “Community Partner*” |

| CC1 | 30/12,649 | 0 | 0.00% | 8 | 0.06% |

| CC2 | 56/14,435 | 2 | 0.01% | 8 | 0.05% |

| PRR1 | 40/8,615 | 1 | 0.01% | 12 | 0.14% |

| PRR2 | 15/3,241 | 3 | 0.09% | 7 | 0.22% |

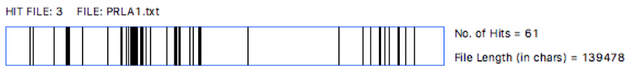

| PRLA1 | 66/20,924 | 4 | 0.02% | 61 | 0.29% |

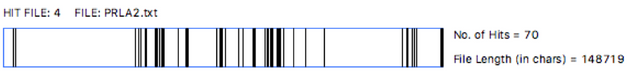

| PRLA2 | 74/20,896 | 2 | 0.01% | 70 | 0.33% |

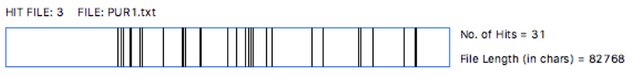

| PUR1 | 31/12,174 | 2 | 0.02% | 31 | 0.25% |

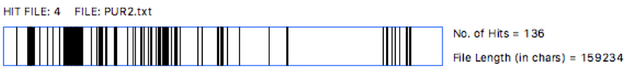

| PUR2 | 86/23,054 | 11 | 0.05% | 136 | 0.59% |

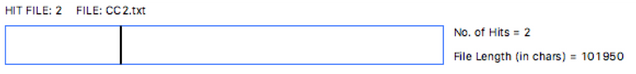

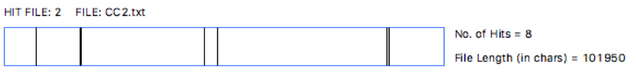

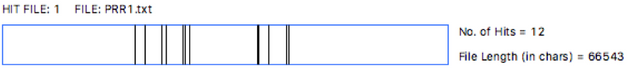

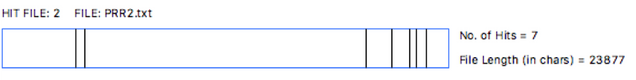

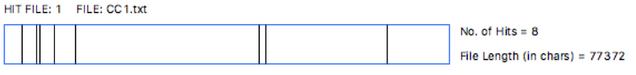

The following are concordance plots to show where these words are positioned in the handbooks, and what that suggests about positionality and importance.

Instances of “Reciproc*”

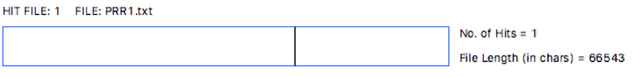

There is one instance of “reciproc*” in PRR1, and 11 instances in PUR2. Also, consider the placement: the one instance in PRR1 occurs in the last third of the handbook, and the 11 instances in PUR2 occur most dramatically in the first third. Typically, concepts that are taught first in a classroom help form the foundation for the rest of the class term. Placing heavier emphasis in the first third of the handbook suggests that PUR2 values reciprocity and intends that concept to be fully comprehended by both instructors and students before the service component.

Instances of “Community Partner*”

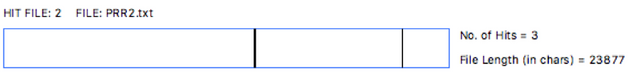

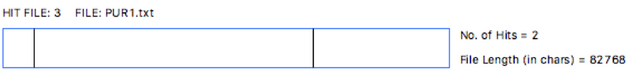

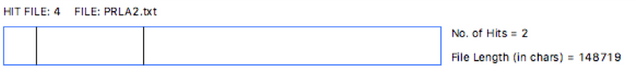

Again, PUR2 has the most instances with a total of 136 instances of “community partner*” whereas PRR2 has only seven instances. Most of the handbooks mention “community partner*” within the first third of the handbook, suggesting that working with a community partner is understood as a high priority. However, PRR1 and PUR1 have no instances until the very edge of the first part. There is a slight absence in the very beginning, suggesting that working with and co-creating knowledge with community partners is also absent in the beginning. The sections on reflective practices and co-creating knowledge will be more described in detail below.

Reflective Practices (Fail to) Problematize Partnerships

The following three examples are sample questions outlined by three handbooks from different types of institutions: CC2, PRLA1, and PRR1. When evaluating reflective practices, the higher rated ones stimulate critical thought on the social, reciprocal, and logistical challenges working with an underserved community through open ended and follow up questions. This section and the section on explicit sections of reciprocity help to contextualize the quantitative data of word instances.

CC2: What do you think will be the most valuable service you can offer at your site? How do others view you at your service site? Has this perception changed over time? If you were the supervisor of your service site, what would you identify [as the most difficult aspect of your service experience] and how would you attempt to solve it? Have you changed any of your attitudes or opinions about the people with whom you have worked? What would you change about your service assignment that would make it more meaningful for you or other service-learning students? How effective did you judge your service to be? [my emphasis]

CC2 adequately addresses the social issues that arise between university and community partners; however, there is no follow up when asking about evolving perceptions and attitudes toward each other. Additionally, they are phrased as closed ended questions, suggesting that further reflection is neither required or prioritized. Second, the student is asked what they would change about the service assignment to make it more meaningful for the student and other students. There is no mention of how the community partners could have a more meaningful experience. Last, the effectiveness question presumes the service was effective. There is no prompt to ask if students thought their service was effective or ineffective. Questions like these presume the service work is going to be a success at the very least.

PRLA1: Think back to your interactions with the child you are working with in the classroom or a child you have observed. Identify and describe specific examples of the cultural traits in oral communication you have seen. Now that you have a better understanding and awareness of that communication behavior, how might you respond or engage in an oral communication exchange with someone of that cultural or ethnic group in the future? What was your behavior or interpretation of a similar situation in the past? How do you think an individual from a different cultural or ethnic group feels when they are orally communicating with a dominant group? How would you feel if the situation was reversed and you were the minority attempting to communicate with others? [my emphasis]

Right away, PRLA1’s sample prompts help stimulate discussion about the cultural and social issues by suggesting that communication styles may differ depending on culture. The prompts ask students to reflect on past experiences working with this demographic or another demographic different from the student’s, and hopes to promote empathy by placing the student in another person’s perspective.

PRR1: What do you expect will be the impact on the service recipients of this service activity? What do you think about the population being served by this activity? Do you think the service recipients are benefiting from this service? Was the community problem addressed through your service? How have your views about the population served changed? Did you benefit from participation in this service activity? [my emphasis]

PRR1’s sample questions revolve around the server-served mentality that plagues SL pedagogy. Right away the community partners are referred to as “service recipients” and those that are “served” rather than partners and co-creators. The struggle with these sample questions is that the questions are asking what is needed to be asked: impact level on community, social issues, and evolving perceptions. However, these questions are all framed around the concept that university partners serve and community partners are served.

Co-Creating Knowledge

The following three examples are sections highlighting the reciprocal co-creating knowledge partnerships from three different types of institutions: PRR2, PRLA2, and PUR1. When evaluating sections of co-creating knowledge partner-ships, the highly rated ones demonstrate explicit parameters of what constitutes equitable partnerships. Unlike reflective practices, which are implicit, these sections are explicit in (not) promoting reciprocity.

PRR2: Community partners provide organizational orientation and training for the position, providing a clear understanding of what is expected of the students. The site supervisor will guide and evaluate the students, and may be asked to provide a brief evaluation at the conclusion of the service. [my emphasis]

PRR2 suggests a lack of partnership with community members due to the phrase “may be asked to provide a brief evaluation.” Partners create, implement, and evaluate together. If community partners are relegated to a contingent or optional role, there is no partnership.

PRLA2: Keep in mind that the community and the clientele are not a teaching or research laboratory. The notion of community as laboratory assumes a false hierarchy of power and perpetuates an attitude of institutional superiority. Basic goals of service learning include community development and empowerment. For these goals to be realized, faculty and community must be equal partners and view themselves as co-educators. [my emphasis]

PRLA2 is explicit in its call to treat university and community members as equal partners. This section describes the consequences of treating community partners as anything but partners, and reminds readers the purpose of SL.

PUR1: Once you have identified an authentic need, you must work collaboratively with the community partner to determine how your students can meet this need. [my emphasis]

PUR1 positions community partners as partners only after identifying an authentic need rather than co-creators at the very beginning. Authentic community needs are identified with community partners, not before the collaboration. This section forgoes the collaboration and instead, positions the university partners as actors of privilege and power “fixing” a problem they have identified within a community, further reinforcing the server-served mentality.

SL handbooks are confusing, inconsistent, and insufficient. As a whole, they do not prioritize community voice. What does this mean for (in)experienced instructors or instructors who, as Cushman argues, are “overworked, transitory, and underpaid” and are not provided enough time, resources, or funding to create in-depth SL experiences for their students and community partners (50)? Due to this inconsistency with SL handbooks, reciprocal partnerships are not always being achieved, reducing the SL experience to disjointed interactions that should be assets in strengthening communities, promoting civic engagement, and empowering all stakeholders in uncharted learning potential.

Action Items for the Service Learning Classroom

Since SL handbooks range from helpful to hurtful, I have compiled a short list of takeaways in no specific order that will help me stay consistent as an advocate for reciprocal partnerships, providing commentary as it applies to my current SL partnership.

1. Dialogue: Talk with your community partner. Develop a rapport and mutually agreed upon expectations.

Nicole (name changed) is my community partner in the SL project partnering my university students and her middle school students. I made a focused effort in getting to know her because good partnerships need good chemistry.

2. Define Relationship: Set expectations for which goals each partner will fulfill during the service learning project.

Nicole and I set boundaries for what was expected of each other once we identified an authentic community need. She is more big picture (concepts and themes), and I’m more little picture (logistics).

3. Address Authentic Needs: Authentic needs should come from the community. University partners shouldn’t im pose solutions to perceived problems.

Nicole and I had weekly meetings where we talked about her middle school students and what they needed most in life. We also discussed the general demographic of my students (they change each semester). A partnership between my students with their advanced research skills, and her students with their budding SL projects would be the best fit.

4. Make Timeline: A flexible and attainable timeline should be created collaboratively by both university and com munity partners.

Since Nicole and I met each week, we made sure to check in to ensure that tasks got checked off, expectations met, and open communication continued.

5. Assess Together: Community partners should be a part of the design, teaching, and assessment process. Com munity voice should be heard.

We would discuss the strengths and weakness of every interaction between the middle school and university students. We constantly thought about how our students could be more supported. How could we tweak the next lesson plans to address those concerns?

6. Reflect on Relationship: Is your relationship with your community partner working? How could it be improved to better promote community voice?

Since I’ll be teaching at my institution for the next four years, we made a commitment to continue SL projects between our two groups of students as long as it was helpful and made sense for each of our groups of students’ personality and intentions.

Plans for Further Service Learning Research

As a SL researcher, I am always looking for more effective ways to approach reciprocity in SL classrooms as well as shed light on factors that prevent (in)experienced instructors from successfully cultivating reciprocal partnerships. I plan to examine the following research questions:

How does an institution’s service learning handbook change depending on its institution’s evolving social context?

How are institutional mission statements reflected in service learning handbooks?

Based on instructors’ interpretation of service learning handbooks, how is reciprocity applied in the curriculum?

“Ethically Tenuous Territory” Needs More Exploration

SL is an “ethically tenuous territory” that deserves critical attention (Jagla 74). This small corpus study has shown that SL handbooks are inconsistent. Gee believes “the fact that people have differential access to different identities and practices, connected to different sorts of status and social goods, is a root source of inequality in society” (30). By helping to ensure the collaborations between university and community partners are co-intentional, despite differentiated funding, opportunities, and departmental backing, we can try to make navigating the “ethically tenuous territory” of SL more explicit, equitable, and reciprocal.

Works Cited