Spring Course Spotlight – Special Topics: Food & Mental Health

METML 610 E1 – Special Topics in Gastronomy: Food & Mental Health will be taught by Chad Bradford (MET Gastronomy alum) in Spring 2026. This online course will have a weekly live classroom session via Zoom (that will be recorded) and can be taken synchronously or asynchronously.

What are the unconscious motivations for the foods we choose? Is alcohol really linked to creativity? And what does the infamous “Twinkie Defense” really tell us about food, law, and psychology?

This spring, the BU Gastronomy Program is offering a new course, Food and Mental Health, taught by Chad Bradford, MD, MA. A forensic psychiatrist, retired Navy Captain, and BU Gastronomy alum, Dr. Bradford combines mental health expertise with a gastronomer’s perspective to guide students through the dynamic, bidirectional relationship between food and the mind.

This interdisciplinary course challenges students to examine food using psychology, neuroscience, sociology, art, media, and more. They will tackle topics such as the gut-brain axis, food as a performance of identity, cooking as therapy, the psychology of consumer marketing, and mental health in the food industry.

The semester culminates in a collaborative Food & Mental Health Cookbook, where students blend scholarly analysis with creative recipe design. Not just a collection of recipes, it is an exploration of how our cravings, identities, and cultural symbols come together on the plate. Students will leave equipped to apply these psychological insights in culinary, entrepreneurial, and cultural settings.

Food and Mental Health (MET ML 610 E1) is open to BU graduate students from all disciplines. Whatever your background, you will discover new ways to think about food, yourself, and the world.

Keep an eye on the Spring 2025 course listings and join us for a unique exploration of what links mind and meal.

Registration is open now!

Graduate Spotlight- Anthony Zamorra

We recently caught up with Anthony Zamora (@anthonyjzamora), one of our Professional Culinary Arts Program alums, who visited Chef Jody Adams and General Manager Harry Asimis to stage at La Padrona (@lapadronaboston) while in Boston. Learn more about his experience below:

How have the BU Culinary Arts programs helped you and how do you still feel connected to the program today?

"The program at BU helped me tremendously by opening up my perspective to all the things I didn't know about food and the industry. The program also allowed me to connect with mentors I still have today! Since earning my certificate in 2016, I keep up with my directors, the program on social media, and have even popped over to the classroom when I've visited Boston."

What does your regular day look like as a nutrition chef for a professional team?

"As the Vice President of Nutrition, Culinary, and Hospitality, I get to work closely with very talented individuals in diverse settings. We cover sports performance nutrition, culinary, and hospitality! When I'm not working hands-on with my teammates, we are usually planning for the next week, month or future seasons. I meet with managers and teammates regularly to review goals, brainstorm ideas, or troubleshoot issues. My team is continuously redefining the definition of hospitality in sports and challenging conventional practices. I am currently designing the kitchen and dining room space of Utah's new NHL practice facility."

Why did you choose to stage at La Padrona with Chef Jody Adams?

"I called Lisa Falso and told her I would be in Boston on a work trip and that I was looking for a stage. I explained to her how I was trying to grow. Hospitality, team building, and delivering high level experiences were all at the top of my list. She recommended La Padrona and Chef Jody, as she thought I would connect well with them and gain a lot of value. Chef Jody's experience in the industry was incredible to learn from, and she shared with me several gems as I continue my career."

Do you have any future plans post-staging?

"Chef Jody and Harry Asimis, GM of La Padrona, both helped open my eyes to see what's possible in hospitality from the inside out. I plan to keep dreaming, building, and to redefine the hospitality experience in professional sports and in the state of Utah. Additionally, I wrote Lisa Falso, Chef Jody, and Harry thank you cards. I believe it's always important to send a card in the mail."

Zamora is the VP of Nutrition, Culinary, and Hospitality at the Smith Entertainment Group, overseeing chefs and dietitians for The Utah Jazz, The Utah Hockey Club, and @experiencetheunderground. He earned his certificate in 2016, continuing to keep close relationships with past directors and mentors and even popping into the classroom when visiting Boston. He contacted our assistant director Lisa Falso with interest in hospitality and team building before being recommended to La Padrona. Chef Jody is a core instructor for our Professional Culinary Arts Program.

Zamora is the VP of Nutrition, Culinary, and Hospitality at the Smith Entertainment Group, overseeing chefs and dietitians for The Utah Jazz, The Utah Hockey Club, and @experiencetheunderground. He earned his certificate in 2016, continuing to keep close relationships with past directors and mentors and even popping into the classroom when visiting Boston. He contacted our assistant director Lisa Falso with interest in hospitality and team building before being recommended to La Padrona. Chef Jody is a core instructor for our Professional Culinary Arts Program.

Summer Course Spotlight- Special Topics in Gastronomy: The Language of Wine

METML 610S B1 – Special Topics in Gastronomy: The Language of Wine will be taught by Professor Ariana Gunderson in Summer 2025. This in-person course will meet twice a week from 6/30 to 8/8 on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 6 to 9:30 PM.

This course is in the discipline of Linguistic Anthropology, and we will be doing plenty of fieldwork together! We will, as a class and on our own, find and analyze examples of people talking about wine in many different ways. Students will learn to compose transcripts, closely read samples of natural language, and conduct linguistic anthropological fieldwork to study language in social life. We will go on field trips together to find and analyze wine talk 'in the wild' and students will get to do some of their own fieldwork in the wine worlds they have access to or are most curious about. We will tackle robust theories of language together, with plenty of support and camaraderie, and students will leave this class with a strong sense of accomplishment in having learned an introduction to the major themes, theories, and research methods of linguistic anthropology. We will have units on the prestige of wine talk, winemaking, the natural wine world, and more.

Anyone who is curious about language, how cultural worlds are constructed, and the social life of wine will enjoy this class. Students need no prior experience with linguistic anthropology or wine talk, and you do not need to consume any wine to participate in or enjoy the course. If you are worried that you don't know how to talk about wine the 'right way,' that makes you an excellent outside observer to the phenomenon and your insights will be critical to the class! Join us!

Summer Courses Spotlight

With warmer weather around the corner, we are spotlighting some of the exciting elective courses that students will be able to take this summer semester. Check them out below:

METML 702S E1, Special Topics in Food & Wine: Food, Documentary & Advocacy will be taught by Dr. Potter Palmer in Summer 2025. This online course will meet once a week from 5/6 through 6/23 (meeting times TBA).

Through an exploration of seminal works in the genre, this course will explore the intricate interplay between food, documentary filmmaking, and advocacy. The course will equip participants with the theoretical frameworks, practical skills, and a deeper understanding of visual storytelling necessary for critically assessing and producing documentaries that serve as vehicles for advocacy and social change within food studies. By the end of the course, students will make their own short documentary.

Course Objectives:

1. Analyze Documentary Techniques

a. Critically analyze documentary films about food systems, sustainability, ecology, and

social justice.

b. Identify and evaluate documentary techniques and modes of storytelling used in

conveying messages and advocating for awareness or change.

2. Cultivate Media Literacy:

a. Enhance media literacy to critically assess the credibility, bias, and intent behind food-

related documentaries.

b. Understand the role of media in shaping public perception and policy around food issues.

3. Develop a Personal Advocacy Project:

a. Learn the steps to conceive, plan, and execute a documentary film project.

b. Identify a specific food-related issue or subject of personal interest or concern.

c. Plan and execute a mini-project utilizing documentary techniques and modes of

storytelling.

MET ML 722, Studies in Food Activism will be taught this Summer 2025 on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 6:00-7:30 p.m. by José López Ganem, with a travel component to Boston, Massachusetts (from July 31 to August 2, 2025).

This class will explore academic and practical efforts on food activism and citizens' efforts to promote social and economic justice through food practices. Either by outright challenging existing structures or supporting philanthropic schemes to mitigate externalities, the space of individual expression and group pressure in food is vast, covering the terrain from the field to the market shelf, from the raw product to the written word. Our time together will focus on exploring diverse, US-based, individual and collective forms of food activism including veganism, gleaning, farmers' markets, organic farming, fair trade, CSAs, buying groups, school gardens, anti-GMO movements, family foundations, among others.

To test the theory and understand the daily complexities of the food activist, the course includes a 3-day trip to Boston, Massachusetts, where we will visit, engage, and evaluate a series of operations that seek to intervene in the way food is grown, transported, cooked, marketed, purchased, recycled, and beyond.

Students interested in learning more about their own activist voice or pursuing a career in the food activist, nonprofit, or philanthropy sector, will find the most value in engaging the curriculum. Moreover, this class will be relevant to anybody that considers themselves an “active” or “aware food consumer.”

In a time where political engagement reaches sectors sometimes misperceived far from The Hill, discover how the taste of your favorite vegetable, the location of a snubby supermarket, or the persistent existence of unhealthy ingredients were decided by predominantly political processes. Above all, come to understand your role as a food scholar on how to participate in its evolution.

Course Spotlight- “Bake Like a Pro”

We are thrilled to announce we will be running “Bake Like a Pro” next semester: The hands-on, pared-down version of our professional pastry arts certificate program, designed for home bakers and aspiring pastry chefs alike. No experience necessary! In this class students will tackle the basics of pastry making, master time management skills and learn the functions of ingredients and their role in baking. You’ll gain knowledge about the science of baking and how to master essential techniques, all while developing good kitchen practices and habits.

We are thrilled to announce we will be running “Bake Like a Pro” next semester: The hands-on, pared-down version of our professional pastry arts certificate program, designed for home bakers and aspiring pastry chefs alike. No experience necessary! In this class students will tackle the basics of pastry making, master time management skills and learn the functions of ingredients and their role in baking. You’ll gain knowledge about the science of baking and how to master essential techniques, all while developing good kitchen practices and habits.

Classes take place once a week in our state-of-the-art kitchen and are taught by a team of highly acclaimed instructors who also teach in our professional pastry arts program, including Chef Janine Sciarappa and Chef Brian Mercury (instructors subject to change). While completion of this course does not result in a certificate, it offers a scaled-down version of our professional pastry arts program. The course covers all the basic core skills with a focus on key recipes and techniques.

For more about the course, we caught up with Chef Janine Sciarappa, Lead Instructor of BU’s Pastry Arts program.

- What type of student is this course really for?

"This class is really geared for anyone who has a passion for pastry. Whether you're a home baker or just really love something sweet, this course is really for someone who is passionate about learning. It makes a great gift too!"

- What should students expect a typical class period to look like?

"In a typical class period, students will be given instructions on how to execute a recipe, then working individually or in groups, they will bake 2 to 3 recipes over the course of the night. We end each session with time to discuss results and give feedback. And then the best part, students get to take all of their pastries home to share with their friends and family!"

- What material is covered in this course?

"Topics include cookies, meringues, cakes and decorating, laminated doughs, custards, tarts and pies, pâte à choux, pastry creams, ganache and breakfast pastries. Everything taught in this course will be sweet, so we will not be working with bread or savory pastries."

- What will students take away from this course?

"My hope is to teach them all of the tips and tricks to basic baking. I want to take the mystery out of complicated and advanced desserts. But above all, because this kind of program works better for those with busy lives, I want to cultivate an environment where students can come in to escape the world and make/eat beautiful things!"

---

Course details— Non-Credit Cost: $1,800, Meets: Tuesdays 6:00 – 8:45 pm, September 9th to December 9th

Signup here.

Course Spotlight- World Food Systems & Policy

MET ML 720A1, World Food Systems & Policy will be taught this spring by Ellen Messer, Ph.D. Anthropology.

Global societies in 2025 confront major challenges to ensure that all people can feed themselves sustainable, healthy diets and enjoy basic human security in a warmer, more crowded and interconnected world threatened by climate change, global pandemics, and structural violence.

Through readings and discussions, course participants acquire working knowledge of the ecology and politics of hunger, food security, and nutrition, and the evolution of global-to-local food systems and diets. Overviews of world food situations and international institutions are combined with analysis of more detailed national and local-level case studies that connect global to national and local food situations, crises, and responses.

Key Policy Questions Explored:

- How many are hungry and why? What are world food situations and priority policy concerns in 2024-2025, in contrast to the late 20th century and pre-pandemic 2020?

- How stable and equitably distributed are world food supplies? Which agriculture, nutrition, and related technology and trade issues have advanced or declined on the world and national food-policy agendas, with what impacts on food supply-chain stability, sustainability, safety, health and nutrition?

- Are animal-source foods necessary for human health and well-being? What should be the roles of livestock, animal protein (meat, seafood, dairy), and meat substitutes in diets favoring planetary and human health? At what scale(s)?

- Can traditional, or more diversified agro-ecological agricultural methods, feed the world?

Learning Objectives:

- Master food-system, food-value-chain, food-security, food-sovereignty, and human-rights terms of analysis at multiple (local to global) scales and demonstrate their interconnections in short weekly critical reviews and food-focused mid-term country-level assignment and final country report.

- Evaluate the relative merits, deficiencies, and overlaps of comparative advantage (markets and trade) vs. food-first (food sovereignty and food security) policies; and “basic needs” (Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) vs. “human rights/rights-based” food-policy approaches in mid-term and end-of-term evidence-based national case studies.

- Navigate the international agricultural, food, nutrition, and health agencies that monitor and evaluate food and nutrition and become a food-and-nutrition policy expert on a particular country, its hunger situation, and its significance in international food production and trade.

Course Spotlight- History of Wine

METML 632 A1, History of Wine will be taught by instructor Jacquelyn Groeper, CSW on Tuesday nights from 6:00 PM – 8:45 PM.

In this course we explore the long and complex role wine has played in the history of human civilization. We survey significant developments in the production, distribution, consumption and cultural uses of grape-based alcoholic beverages in the West. We study the economic impact of wine production and consumption from the ancient Near East through the Roman Empire, Europe in the Middle Ages and especially wine's significance in the modern and contemporary world. Particular focus is on wine as a religious symbol, a symbol of status, an object of trade and a consumer beverage in the last few hundred years.

In this course we explore the long and complex role wine has played in the history of human civilization. We survey significant developments in the production, distribution, consumption and cultural uses of grape-based alcoholic beverages in the West. We study the economic impact of wine production and consumption from the ancient Near East through the Roman Empire, Europe in the Middle Ages and especially wine's significance in the modern and contemporary world. Particular focus is on wine as a religious symbol, a symbol of status, an object of trade and a consumer beverage in the last few hundred years.

More about the class from Jacquelyn:

"Wine is not just a beverage. Its pre-historical evolution throughout Western Civilization has influenced history, culture, politics, agriculture, science... This is what I find intriguing about wine. It is a natural product that first fascinated, then became a necessity, until ultimately impacting all facets of society. As we explore this 8,000 year history, we will also taste different styles of wine to understand how and why they developed. We will examine ways in which contemporary issues such as climate change, politics, and labor arrangements are influencing the production of wine today. Overall, when students understand the intricacies of the history of wine, as is similar with food, I believe there is more of an appreciation for all it brings to the table."

Course Spotlight- Food Marketing

MET ML565, Food Marketing will be taught by our newest part-time faculty member Robin Cohen in Spring 2025. The class will meet on Mondays from 6 to 8:45 PM.

Food Marketing applies the fundamental concepts of marketing and brand management to the food industry, with a particular focus on the New England culinary scene. The food marketing space covers many distinct sectors including products, restaurants, retail outlets, services such as catering, culinary travel and tours, and food events. Although many marketing fundamentals

Food Marketing applies the fundamental concepts of marketing and brand management to the food industry, with a particular focus on the New England culinary scene. The food marketing space covers many distinct sectors including products, restaurants, retail outlets, services such as catering, culinary travel and tours, and food events. Although many marketing fundamentals

apply universally, we will examine how each part of the food industry requires specific methodologies, tools, and measures for success.

Even within sectors, tools and approaches will vary. You might promote a small neighborhood shop differently than you would market a nationwide grocery chain. You will have an opportunity to learn how marketing resources, such as social media and AI, are leveling the playing field-allowing the smallest businesses to compete in ways they never could before. The course will present marketing needs from the consumer, manufacturers, maker, buyer, distributor, and service provider point of view. Presentations by a diverse group of industry leaders, readings, and real-world case studies will broaden our understanding. A hands-on project will fuel learning and creative thinking with students selecting to study and report on one specific product or service company.

Course Spotlight- Culinary Tourism

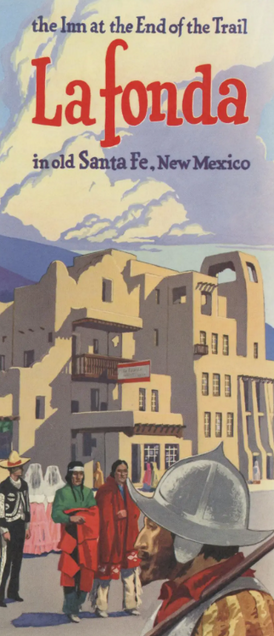

MET ML 692, Culinary Tourism will be taught this Spring 2025 on Thursdays from 6:00-7:30 p.m. by José López Ganem, with a travel component to New México (United States) during the BU Spring Break ‘25.

MET ML 692, Culinary Tourism will be taught this Spring 2025 on Thursdays from 6:00-7:30 p.m. by José López Ganem, with a travel component to New México (United States) during the BU Spring Break ‘25.

Among the higher echelons of the Food Studies canon, Lucy Long’s Culinary Tourism provides a time-proofed definition of this activity “as the intentional, exploratory participation in the foodways of an other.” Our time is plagued by mediatic invitations to

discover (e.g. Anthony Bourdain), re-discover (e.g. Eva Longoria), and re-claimed (e,g.Karen Cantor), via the physical experience of immersing ourselves in foodways -mostly in their place of practice, although not always - that are not part of our daily

routine or were not staples of our upbringing. Based on this definition, a food studies scholar happens to be a conscious culinary tourist for life.

On this course’ second reiteration, Culinary Tourism will be a space to understand the thought and method that have gone into understanding the temporal presence of ourselves in the food customs of another. From the rich history of how we have engaged in the ludic pursuit of food beyond our comfort, to the industries and mechanisms that have made this quest possible. Like Long suggests, this course will engage how food is consumed, prepared, and served to a visitor; and even how foodways can be observed and understood by a stranger’s gaze.

On this course’ second reiteration, Culinary Tourism will be a space to understand the thought and method that have gone into understanding the temporal presence of ourselves in the food customs of another. From the rich history of how we have engaged in the ludic pursuit of food beyond our comfort, to the industries and mechanisms that have made this quest possible. Like Long suggests, this course will engage how food is consumed, prepared, and served to a visitor; and even how foodways can be observed and understood by a stranger’s gaze.

Moreover, the class will undertake a practicum component during our University’s Spring Break (from Tuesday March 11 to Sunday March 16) to the State of New Mexico. The region’s multicultural makeup yet challenging weather makes this corner of the United States a testing ground for the theory we will learn in the classroom. Participation on this trip is mandatory.

Students will be responsible for arranging and paying for flights, lodging, and most meals. The program will be attempting to facilitate the lodging booking process so that all trip participants are staying at the same hotel. The program will cover in-ground

transportation to and from activities, plus any entry fees for those activities, such as museum tickets.

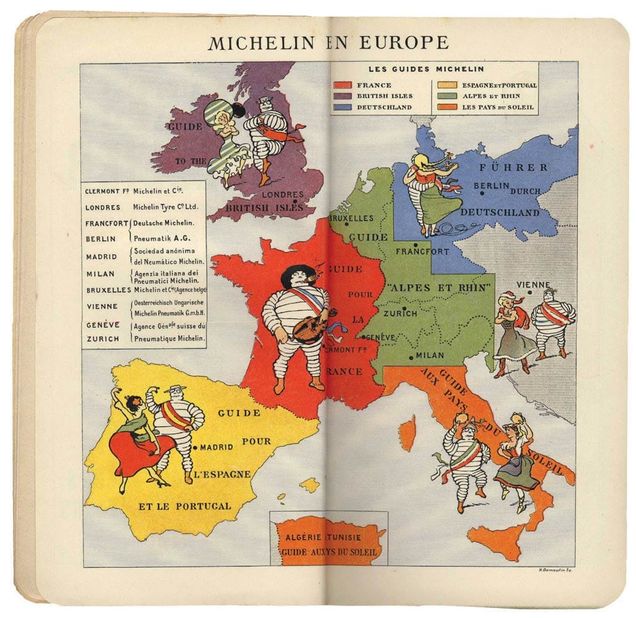

As the Michelin Guide invites the traveler, may this class be so exceptional in our roster of electives that it is “worth a special journey.”

Photo Credits

1. © Michelin Guide / France

2. © La Fonda Inn / University of New Mexico - United States

3. © Harry Kersh and Joe Avella / Food Tours - United States

Course Spotlight- Fundamentals of Wine

METML 649 A1, Fundamentals of Wine will be taught this spring by Ara Sarkissian, CWE and will meet on Mondays from 6 to 8:45pm

For students without previous knowledge of wine, this introductory survey explores the world of wine through discussions, tastings, food and wine pairing, assigned readings, and student presentations. By the end of the course, students will be able to exhibit fundamental knowledge of the principal categories of wine, including major grape varieties, wine styles, and regions; correctly taste and classify wine attributes; and demonstrate an understanding of general principles of food and wine pairing.

[4 credits; $325 lab fee]

To learn more, we touched base with the course instructor, Ara Sarkissian.

- What is the aim of this course? What kind of student is it for?

- What skills/knowledge do you hope students will leave the course with?

- What topic/unit are you most excited to teach?

- What else should students know?