Home

The Role of Trauma-Informed Care for Women in the Criminal Justice System

A background of trauma frequently affects women in the criminal justice system, profoundly influencing their experiences. Their paths into crime are often linked to survival strategies resulting from poverty, abuse, and mental health issues like depression and PTSD (Rousseau, 2025). However, many traditional treatment programs have ignored the crucial role trauma plays in women’s offending by using a one-size-fits-all strategy based on models created for men. This blog post will discuss the significance of gender-responsive, trauma-informed therapeutic approaches for women in the court system. Addressing the close relationship between trauma and criminal conduct is crucial for supporting recovery, rehabilitation, and long-term success. Research has consistently shown that women often enter the system as a result of trauma and socio-economic disadvantage. For many, their offences are intertwined with coping mechanisms for dealing with the long-term effects of victimization (Rousseau, 2025). Substance misuse may be a way to self-medicate, while offences like theft or fraud can arise out of economic desperation. Without addressing these underlying factors, traditional approaches risk perpetuating cycles of trauma and criminal behaviour.

Unlike conventional methods, trauma-informed practices are intentionally gender-responsive, addressing the specific needs and vulnerabilities of women. The development of trauma-informed approaches is grounded in feminist theories of ‘complex trauma’, which recognizes trauma as a prolonged experience of abuse and adversity, often within intimate or familial relationships (Petrillo, 2021). In the UK, trauma-informed practice in women’s prisons draws heavily on Stephanie Covington and Barbara Bloom’s work on gender-specific interventions, which are based on creating safe, respectful, and dignified environments while addressing substance misuse, trauma, and mental health issues through integrated, culturally relevant services (Petrillo, 2021). This allows women dealing with trauma to heal in a supportive environment that acknowledges their unique experiences, fostering resilience and reducing the likelihood of reoffending (Petrillo, 2021). Trauma-informed practices create a foundation for meaningful rehabilitation and personal growth by prioritizing safety, empowerment, and respect. While therapies such as dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), traumatic incident reduction (TIR), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and relaxation techniques have been used to treat incarcerated women with trauma histories, these interventions are not always designed specifically to address trauma in this population and often require a highly trained clinician or staff to implement effectively (King, 2017). While it may be more feasible for previously incarcerated women to access such specialized care post-release, it is much more difficult to provide within the prison setting. Therefore, it is crucial to consider how prison life itself can be improved for women, not just how to support their reintegration once they are released. This is why it is important to have several trauma-informed interventions developed specifically for women in prison, like Seeking Safety, Helping Women Recover/Beyond Trauma, and Beyond Violence (King, 2017).

Although trauma-informed practices have become more popular recently, you may contend that they might not be scalable in large, underfunded and overcrowded jail systems with little access to highly qualified medical professionals. This poses an important question regarding the viability of broad distribution in the absence of sufficient resources and staff. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that although trauma-informed care provides a sympathetic response to women's particular experiences, the legal system itself frequently adopts gender-specific methods slowly, which can result in uneven implementation among institutions. We must think about systemic changes that prioritize trauma-informed techniques and enhance general prison conditions if we are to effectively close these gaps. This could entail promoting policy changes, providing post-release continuity of care, and educating general staff on trauma-informed practices.

References:

King, E. A. (2017). Outcomes of Trauma-Informed Interventions for Incarcerated Women: A Review. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(6), 667-688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15603082

Petrillo, M. (2021). ‘We've all got a big story’: Experiences of a trauma‐informed intervention in prison. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 60(2), 232-250.

Rousseau, D. (2025). Module 4: Implementing Psychology in the Criminal Justice System. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Childhood Trauma & Criminality: How Public Safety and Support Systems Fail Vulnerable Youth

Child abuse is a national safety crisis, with 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys in the United States being said to experience some kind of child abuse, whether that be physical, emotional, sexual abuse or neglect (National Children’s Alliance, n.d.). The consequences of childhood abuse and trauma have been researched extensively across field of social sciences, psychology, developmental neuroscience and more, as society has begun to realise to extent to which these traumatic experiences in childhood can influence later behaviour and mental health issues. In recent years, studies have examined the rippling effects childhood trauma can have on victims even decades after the victimisation, evidencing how trauma can hinder work success (Paulise, 2023), can detrimentally affect romantic relationships and marital success (Nguyen et al., 2017) and is significantly associated with varying chronic health problems (Afifi et al., 2016). The effects of childhood abuse are unbounded.

Child abuse is a national safety crisis, with 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys in the United States being said to experience some kind of child abuse, whether that be physical, emotional, sexual abuse or neglect (National Children’s Alliance, n.d.). The consequences of childhood abuse and trauma have been researched extensively across field of social sciences, psychology, developmental neuroscience and more, as society has begun to realise to extent to which these traumatic experiences in childhood can influence later behaviour and mental health issues. In recent years, studies have examined the rippling effects childhood trauma can have on victims even decades after the victimisation, evidencing how trauma can hinder work success (Paulise, 2023), can detrimentally affect romantic relationships and marital success (Nguyen et al., 2017) and is significantly associated with varying chronic health problems (Afifi et al., 2016). The effects of childhood abuse are unbounded.

Criminality and childhood victimisation

Though childhood abuse is a hard to measure hidden phenomenon, the statistics we do have show that children who experience abuse, neglect, or exposure to violence are at higher risk of engaging in criminal activity later in life.

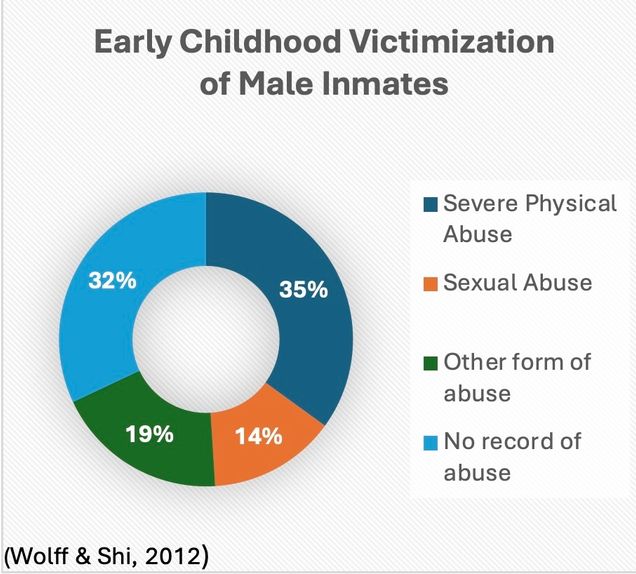

In the U.S., studies have reported as many as 1/6 male inmates having experiences physical or sexual abuse before the age of 18 (Wolff & Shi, 2012) – and this is the low end of the scale. Other studies, such as one by Robin Weeks and Cathy Spatz Widom (1998) for the National Institute of Justice found 68% of the male inmates in their sample reported some form of childhood abuse before the age of 12 (physical, sexual, neglect). Scholars have theorised this is linked to the Cycles of Violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989; Widom & Maxfield, 2001), which claims that adverse childhood experiences of violence, abuse or neglect can cause victims to reproduce this behaviour in their adult lives which often leads to violent criminal behaviour.

In the U.S., studies have reported as many as 1/6 male inmates having experiences physical or sexual abuse before the age of 18 (Wolff & Shi, 2012) – and this is the low end of the scale. Other studies, such as one by Robin Weeks and Cathy Spatz Widom (1998) for the National Institute of Justice found 68% of the male inmates in their sample reported some form of childhood abuse before the age of 12 (physical, sexual, neglect). Scholars have theorised this is linked to the Cycles of Violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989; Widom & Maxfield, 2001), which claims that adverse childhood experiences of violence, abuse or neglect can cause victims to reproduce this behaviour in their adult lives which often leads to violent criminal behaviour.

However, I challenge this idea. Instead, I theorise that childhood victimisation of violence itself does not inherently cause more violence, instead it is the experience of violence within a society that fails to protect, support, or care for vulnerable children that fosters these cycles. This phenomenon should be understood through a lens similar to the social disability model: just as disability does not inherently limit a person, but rather society’s failure to provide adequate support does, it is not abuse alone that leads to violence or criminality. Rather, it is the failure of social systems to intervene, protect, and care for trauma-affected children that perpetuates these outcomes.

Systemic Failures and Their Consequences

When we examine the systems in place to both prevent incidents of child abuse and promote healing among known victims, we can see failures of the system to adequately do so at every step of the way. Many politicians and academics defend these failures by using the hidden nature of abuse as an excuse – but research shows there were an estimated 558,899 instances of recorded child abuse in the US in 2022 alone (National Children’s Alliance, n.d.), thus proving there are countless cases that are known and in need of assistance. But what are the systems in place to support these children? And if they are working, why do we see so many past victims of abuse spiral into criminality?

In my opinion, this is because of three main failures of policy and support services:

- Lack of Access to Mental Health Care: Many children in abusive environments do not receive the psychological care needed to process their trauma, leading to behavioural issues that escalate over time through exacerbation and development of mental health issues caused by lack of appropriate intervention and support.

- Underfunded Social Services: Child welfare systems often fail to provide consistent, long-term support, leaving many children vulnerable. Increased funding and allocation of resources could in the long-term prevent increased criminality among this population, and instead help more victims heal and become citizens who contribute positively to society.

- School and Community Gaps: Schools and communities frequently lack the resources to identify and assist trauma-affected children before they enter the criminal justice system. Training should be compulsory for teachers and community workers to help them identify signs of trauma, and to intervene in trauma-informed ways that benefit the child without retraumatizing them.

Breaking the Cycle: What Can Be Done?

To break the ‘cycle of violence’ and criminality associated with childhood trauma, we must shift our focus from reactive to proactive solutions, by working to ensure that abuse survivors receive the support they need to heal and thrive. This calls for a multi-faceted reformative approach to support procedures and legislative prevention policies, that refocuses its aim to break the socially imposed link between childhood victimisation of violence and adult or adolescent criminality.

- Expanding Trauma-Informed Care must become a priority across a vast range of public systems including child welfare, education, and criminal justice systems. This involves comprehensively training teachers, social workers, law enforcement, and healthcare providers to recognise signs of trauma, and to deal with these situations in ways that do not retraumatise children.

Strengthening Family and Community Support Systems should also be a priority. Government funding should be re-allocated to promote evidence-based programs that target risk-factors for child abuse and have proven to reduce instances of violence. For instance, the program SafeCare which visits parents at home to help promote positive and safe relationships between caregivers and children.

Strengthening Family and Community Support Systems should also be a priority. Government funding should be re-allocated to promote evidence-based programs that target risk-factors for child abuse and have proven to reduce instances of violence. For instance, the program SafeCare which visits parents at home to help promote positive and safe relationships between caregivers and children.- Reforming the Juvenile Justice System would also help to aid trauma-affected youth in a real way instead of simply criminalising them. This could be done through diversion programs that connect with trauma-affected youth who may have encountered the criminal justice system. But instead of providing them with punishment, programs could be focussed on counselling efforts, and mental health support to address the root cause of early criminal behaviour.

- Improving Accessibility to Mental Health Resources would be a vital part of this process. Many trauma survivors - particularly those from marginalized communities - face significant barriers to receiving psychological care, especially in a nation lacking universal healthcare. Instead, systems could be put into place to provide victims with this care through community-based organizations and clinics, or even school based mental health programs – to ensure that children without access to health insurance and adequate health care can still access the tools they need to heal.

- Advocating for Policy Change would work to address systematic failures that prevent the prioritisation of child welfare. This could include allocating more funding for child protective services, improving foster care monitoring systems, and enforcing stricter measures for cases of institutional negligence. By shifting legislative priorities towards prevention and rehabilitation rather than punishment, we can begin dismantling the structural barriers that perpetuate cycles of trauma and criminality.

By addressing the root causes of violent behaviour through trauma-informed care and providing survivors with the tools they need to heal, we can create a future where childhood victimization of violence does not dictate one’s path in life.

Reference list:

Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M., Cheung, K., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., & Sareen, J. (2016). Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health reports, 27(3), 10–18. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26983007/

National Children’s Alliance. (n.d.). National Statistics on Child Abuse. https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/media-room/national-statistics-on-child-abuse/

Nguyen, T. P., Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (2017). Childhood abuse and later marital outcomes: Do partner characteristics moderate the association? Journal of family psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 31(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000208

Paulise, L. (2023, June 9). 3 Ways Childhood Traumas Impact Work Productivity and Well-Being. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lucianapaulise/2023/06/09/3-ways-childhood-traumas-impact-work-productivity-and-well-being/

Weeks, R., & Widom, C.S. (1998). Early Childhood Victimization Among Incarcerated Adult Male Felons. National Institute of Justice: Research Preview, U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/fs000204.pdf

Widom, C. S. (1989). The Cycle of Violence. Science, 244(4901), 160–166. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1702789

Widom, C.S., & Maxfield, M.G. (2001). An Update on the “Cycle of Violence”. National Institute of Justice: Research Preview, U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/184894.pdf

Wolff, N., & Shi, J. (2012). Childhood and adult trauma experiences of incarcerated persons and their relationship to adult behavioral health problems and treatment. International journal of environmental research and public health, 9(5), 1908–1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9051908

Breaking the Chains of Trauma: A Look at Incarcerated Women

The criminal justice system, as it is currently structured, often overlooks the particular needs of incarcerated women, perpetuating a cycle of victimization and imprisonment. Unlike their male counterparts, many women enter the system not driven by the pursuit of power or financial gain but as a result of survival-related crimes—offenses rooted in abuse, extreme poverty, and substance dependence. When dealing with female offenders, we should treat them differently than male offenders, because "It is crucial to recognize that men and women have different needs and experiences, meaning that treatments should be equitable, but not necessarily equal" (Rousseau, 2025). Women's realities demands a fundamental shift in how we approach their rehabilitation, recognizing and addressing the different traumas that permeate their lives.

Trauma is not the exception; it is the norm. A significant number of these women have experienced physical, sexual, and emotional abuse throughout their lives, often beginning in childhood. Additionally, many are the primary caregivers for their children, which exacerbates their vulnerability and the consequences of their incarceration. This background of trauma profoundly impacts their mental health and well-being, increasing the risk of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other mental health challenges.

Stephanie Covington (2007) highlights how traditional correctional policies often fail to address the unique needs of women, reinforcing a system that punishes them for the very experiences that led to their incarceration in the first place. Instead, Covington advocates for relational and trauma-informed interventions that address victimization, caregiving roles, and mental health concerns. Gender-responsive programs provide an opportunity for comprehensive rehabilitation, improving reintegration and reducing recidivism.

But how does this translate into practice? First, it is crucial to build trust between incarcerated women and mental health professionals. This can be achieved through staff training on the prevalence and impact of trauma, as well as the implementation of peer support programs that foster a sense of community and mutual understanding.

Additionally, treatment programs must be specifically designed to address the unique needs of women who have experienced trauma. These programs should offer; individual and group therapy focused on trauma, substance abuse treatment, development of social and emotional skills, parenting support and family reunification assistance, and the promotion of physical and emotional safety, allowing women to process their traumatic experiences in a supportive environment.

Post-release programs are also essential. Mental health and addiction treatment, PTSD and co-occurring disorder therapy, as well as social skills development and emotional support, are critical components of effective rehabilitation efforts.

By prioritizing relational and trauma-informed interventions, the criminal justice system can begin to address the unique needs of incarcerated women, fostering healing and successful reintegration into society. Breaking the chains of trauma can pave the way toward a more just and equitable future for all incarcerated women, regardless of their past.

References:

- MET CJ 725 O1 Forensic Behavior Analysis. Spring 1, 2025, BU, Prof. Rousseau, D.

- Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2007). Risk-Need-Responsivity Model for Offender Assessment and Rehabilitation.

- Covington, S. S. (2007). The Relational Theory of Women's Psychological Development: Implications for the Criminal Justice System. In R. Zaplin (Ed.), Female Offenders: Critical Perspectives and Effective Interventions (pp. 135-164). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

- Orr, C. et al. (2009). America's Problem-Solving Courts: The Criminal Costs of Treatment and the Case for Reform. National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

- Rousseau, D., PhD, LMHC, & Elizabeth Jackson, MPH. TIMBo Implementation in a Women's Correctional Facility – MCI Framingham Pilot.

- Walls, S. The Need for Special Veteran Courts.

Vicarious Trauma in the Legal System

The criminal justice system can cause or exacerbate trauma for all actors involved in each channel of the system. Criminal justice professionals as well as inmates experience trauma through law enforcement, courts and law, and corrections.

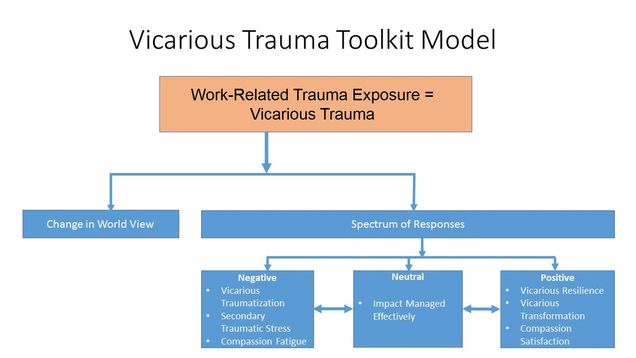

It is common to understand the trauma that can come from both law enforcement and correctional professionals due to high stress and the potential for violent scenarios. However, it is notable to realize that professionals within courts and law can experience trauma as well. A United Nationals article explains the vicarious trauma that judicial system professionals face (Vicarious Trauma, n.d.) Vicarious trauma is “the cumulative inner transformative effect of bearing witness to abuse, violence and trauma in the lives of people we care about, are open to and are committed to helping” (Vicarious Trauma, n.d.). Judges listen to evidence and make decisions with significant implications that affect members of society. This vicarious trauma can cause a negative world view, perceived threats to personal safety, loss of spirituality, or changes in self-identity, fear, empathetic distress, burnout, loss of relationships, mental or physical health issues, depression, or even coping with stress through food of substances” (Vicarious Trauma, n.d.). This proves that the trauma that judicial actors vicariously obtain can affect both their personal and professional lives.

There are three different types of reactions to trauma exposure including negative, neutral, and positive reactions. Negative reactions include vicarious traumatization leading to secondary traumatic stress, compassion fatigue, and critical incident stress (Department of Justice, n.d.). Neutral reaction signifies a person’s resilience, experiences, support, and coping strategies that manage the traumatic material. Positive reactions lead to vicarious resilience and involves drawing inspiration from victim’s resilience to strengthen their own mental an emotional fortitude.

Luckily there has been efforts to address the trauma that judicial professionals have identified. First, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) include wellness aspects in their training conferences to build resilience for judges. They explain ideas of breathing techniques, nutrition, physical exercise, mindfulness practices, self-compassion, and advice from experts to develop tools to reduce stress and mitigate vicarious trauma (Vicarious Trauma, n.d.). Educating professionals early on how to deal with vicarious trauma offers these individuals the best opportunity to have positive outcomes when they face these situations.

Additionally, there are suggestions for coworkers, supervisors, and family members who might identify someone dealing with vicarious trauma. This involves reaching out and talking to them, supporting them, connecting them to resources, referring them to organizational support, allowing flexible work schedules, creating a positive physical space at work, maintaining routine, and more (Department of Justice, n.d.).

While the risks of vicarious trauma is detrimental to both physical and mental health in personal and professional lives, there are solutions. It is essential to educate professionals within the legal system about vicarious trauma, so they have both the knowledge and resources to combat it.

References

Department of Justice. (n.d.). What is vicarious trauma?: The Vicarious Trauma Toolkit: OVC. Office for Victims of Crime. https://ovc.ojp.gov/program/vtt/what-is-vicarious-trauma

Vicarious trauma experienced by judges and the importance of healing. (n.d.). https://www.unodc.org/dohadeclaration/en/news/2021/26/vicarious-trauma-experienced-by-judges-and-the-importance-of-healing.html

Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences and Their Impact on Native American Youth

Introduction

Native American communities have long grappled with a complex web of historical trauma, marginalization, and systemic challenges that have contributed to a disproportionate exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). These experiences—ranging from abuse, neglect, and exposure to domestic violence to the chronic stress of living in communities burdened by poverty and discrimination—are deeply interwoven with the legacy of colonization and forced assimilation. Research by Felitti et al. (1998) highlights that ACEs can have lifelong repercussions, while Evans-Campbell (2008) provides a contextual framework for understanding how historical trauma magnifies these effects in Native communities. As Rousseau (2025) notes, “From being exposed to violence, having educational disabilities, and enduring a life of trauma, most, if not all, juvenile offenders need mental-health services to prevent a further deep-end track into adult crime and adult mental illness”.

The Connection Between ACEs and Incarceration

The link between ACEs and later criminal behavior is well documented. Children who experience chronic trauma may develop maladaptive coping mechanisms that manifest as aggression or risky behavior. When compounded with limited access to quality education and economic opportunities, these factors create vulnerabilities that can lead to arrest and incarceration—a dynamic further explored by Chandler et al. (2011). This cycle of disadvantage is not merely a series of isolated incidents but a predictable outcome of systemic neglect and cultural disruption. Rousseau (2025) further explains that “the risk of suicide among juveniles who have entered the juvenile justice system is at an acute level. In fact, suicide is the leading cause of death among youths in detention facilities”.

Mental Health in Native American Communities

Mental health challenges are another critical concern emerging from this cumulative trauma. The forced removal of Native children from their families and communities through policies like boarding schools severed essential cultural ties that once provided resilience and a sense of identity. Such cultural disruption, combined with ongoing socio-economic stressors, has resulted in high rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other mental health conditions among Native American populations—a reality that further complicates the community’s recovery efforts (Evans-Campbell, 2008). Rousseau (2025) reinforces this by stating, “65% to 70% of youth in contact with the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental-health disorder. More than 60% of youth with mental-health disorders also have substance-use disorders”.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

The issue of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) further underscores the intergenerational impact of these adverse experiences. FAS, which results from prenatal alcohol exposure, leads to lifelong physical, behavioral, and cognitive disabilities. Research by May et al. (2009) indicates that the prevalence of FAS in Native American communities is not simply a matter of individual behavior; rather, it is deeply connected to the broader social determinants of health and the stresses that fuel substance misuse during pregnancy. Rousseau (2025) adds, “Alcohol is widely known to have harmful effects on a developing fetus. In fact, alcohol can cause damage in a variety of ways: It can alter the way that nerve cells develop and divide to produce new cells; it can directly kill nerve cells or derange the formation of axons, the projections that send brain messages from one cell to another”. This intergenerational transmission of disadvantage further hinders academic and economic opportunities, thereby reinforcing cycles of poverty and, indirectly, criminal behavior.

Suicide Among Native American Youth

Perhaps the most heartbreaking consequence of this complex interplay of factors is the alarmingly high rate of suicide among Native American youth. The loss of cultural identity, isolation, and the cumulative weight of personal and communal trauma can leave young people feeling hopeless. When these factors converge with barriers to accessing culturally relevant mental health care, suicide can tragically appear as the only escape. Stanley, Hom, and Joiner (2016) document how this interplay of cultural loss, isolation, and unresolved trauma significantly elevates suicide risk among Native youth. Rousseau (2025) states, “Nearly all individuals who attempt suicide exhibit warning signs. These signs can occur in the days or weeks prior to an incident. All individuals working within the criminal justice system should be aware of the signs and symptoms of suicidal behavior”.

Community and Culturally Informed Care

Despite these daunting challenges, there is hope in the commitment to healing through community and culturally informed care. Recognizing the profound impact of ACEs and addressing the root causes of these issues requires an investment in trauma-informed practices, culturally tailored interventions, and robust community empowerment initiatives. Integrating traditional healing practices with modern therapeutic approaches can begin to mend the deep emotional wounds inflicted over generations. Early intervention—particularly in prenatal and early childhood programs—can help mitigate conditions like fetal alcohol syndrome while comprehensive support networks offer the necessary resources to break cycles of poverty, crime, and despair.

Conclusion

Ultimately, addressing the multifaceted challenges faced by Native American youth is not only a matter of policy but also a moral imperative. By acknowledging the historical and ongoing struggles of these communities and committing to solutions that honor their cultural heritage and resilience, there is a path toward a future where every child has the opportunity to thrive. The journey toward healing is long and complex, but with targeted efforts and a deep commitment to justice and equity, the cycle of adversity can be broken, paving the way for a brighter, more hopeful tomorrow.

References

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

Evans-Campbell, T. (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(3), 316-338.

Chandler, M. J., Lalonde, C. E., & Whaley, C. M. (2011). The impact of historical trauma on intergenerational social processes and contemporary behavioral outcomes among Native American families. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 9(1), 23-42.

May, P. A., Gossage, J. P., Marais, A. S., Jones, K. L., Kalberg, W. O., Barnard, R. J., & Hoyme, H. E. (2009). Prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement, 16, 152-160.

Rousseau, D. (2025). Module 1: Thinking Like a Forensic Psychologist. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Rousseau, D. (2025). Module 2: Substance Use. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Rousseau, D. (2025). Module 4: Implementing Psychology in the Criminal Justice System. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2016). Race, sex, and cultural factors influence the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and suicide risk among Native American adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research, 20(4), 514-523

Implementation of Trauma-Informed Services into Real-Life Situations

In 2018, a violent man walked into a hot yoga studio in Tallahassee, Florida; he opened fire, ultimately killing a Florida State University faculty member, Dr. Nancy Van Vessem, and my sorority sister, Maura Binkley (Holcombe et al., 2019). This incident not only shocked the tight-knit community of Florida State and those who knew the victims but also inspired policy changes for hate crimes throughout the state of Florida.

The perpetrator of this heinous crime, Scott Beierle, had many red flags pointing towards an attack such as this, all of which were ignored by law enforcement officials. Beierle had a history of sexual misconduct that started in childhood, as well as a documented hatred of women that spanned throughout his life; he had also received multiple reports of sexual misconduct during the time he served in the military, and he had been fired from substitute teaching jobs throughout Florida for inappropriately touching female students (Holcombe et al., 2019). Law enforcement officials who searched Beierle’s personal items found disturbing journal entries regarding ideas of brutally torturing women, and although Beierle took his own life directly following his attack, the assumed motivation for this crime was his deep-rooted hatred of women.

Although I never knew Maura personally, those who loved her say that she was one of the brightest lights, and there is no doubt in my mind that she would’ve changed the world if she was given the chance to. She was an animal lover, a leader in our sorority, and was planning to move to Germany following her graduation from Florida State (Maura’s Voice, 2024). I got the opportunity to know some of her best friends, her family, and my own sorority sisters who live in her legacy every day, and everyone who had the privilege of knowing Maura was truly rich in life.

A year following the Tallahassee hot yoga shooting, Maura’s Voice Research Fund was launched by Jeff & Margaret Binkley, Maura’s parents. The organization funds research through Florida State’s College of Social Work to address issues of violence and prevent future hate crimes against women. I had the opportunity for two years to work for this amazing initiative to research incel-perpetrated mass violence against women, as well as red-flag laws within Florida. Although sometimes this research was discouraging to look into, the personal relationship I was able to form with those closest to Maura reaffirmed that organizations such as Maura’s Voice have the potential to change policies and prevention efforts, as well as heal trauma over time.

In the aftermath of the attack, trauma is something that many people directly affected by this situation still struggle with. Jeff Binkley is someone that I was fortunate enough to talk to often, and although the pain of losing his only daughter will never leave him, the efforts he puts into maintaining her legacy are so admirable; even through his grief, he still came to our sorority house to talk to all of us, celebrate Maura’s birthday with us every year, and release balloons in memory of Maura. My sorority sisters who personally knew Maura, took so much time to let us get to know her through their eyes, and it truly felt as though she was still with us. Although this was an incident that had the ability to divide our community, it actually brought us all together to work for a common goal: to make sure Maura and Dr. Van Vessem’s stories are never forgotten.

Throughout this course, we have touched on trauma-informed services a few times. In Module 4, it is stated that for individuals to benefit from these services, trauma and coping mechanisms must be taken into account, and the four most important qualities in programs such as this are safety, predictability, structure, and repetition (Rousseau, 2025). Although no formal trauma services were used, I feel as though my sorority was able to implement these qualities to ensure that those who knew Maura were able to cope with their trauma following the shooting. In our sorority house, we had a room dedicated to Maura; it contained all of the decorations from her bedroom, and her parents designed it to reflect Maura’s personality. By far, this room was everyone’s favorite in the house and where we all felt most comfortable to speak about our feelings. It almost felt as if Maura was looking over us in this room, and it gave all of us, as well as Maura’s family and best friends, a place to visit and talk to her. Each year, on Maura’s birthday, we would all participate in a yoga class and then eat her favorite German dishes with her family. And each year, on November 2nd, the day Maura passed, we would talk about the research we were doing to aid in the prevention of attacks like this, and then we would release balloons to honor Maura and Dr. Van Vessem. These actions allowed our community to heal collectively following the shooting and provided those who knew Maura with the support to continue fighting in her legacy for policy changes.

References

Holcombe, M., Chavez, N., & Baldacci, M. (2019, February 13). Florida yoga studio shooter planned attack for months and had “lifetime of misogynistic attitudes,” police say. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/13/us/tallahassee-yoga-studio-shooting/index.html

Maura’s Voice. (2024, June 13). https://maurasvoice.org/#maurasstory

Rousseau, D. (2025, January). Module 4: Implementing Psychology in the Criminal Justice System. Reading.

Trauma of Institutionalization: Is It Possible That an Ex-Convict Will Recidivate Due to Institutionalization?

To begin this blog, I would like to quote: “With one in every 108 Americans behind bars, the deinstitutionalization of prisons is a pressing issue for all those facing the daunting challenges of successfully reintegrating ex-offenders into both their communities and the larger society” (Frazier, Sung, Gideon, & Alfaro, 2015).

Similar to military life, prison is highly structured. The Prisoner is immersed in a disciplined environment where their daily activities are monitored and planned. This raises an important question: might an ex-convict struggle to reintegrate into society after spending so much time in the controlled environment of prison life? When combined with prior trauma—whether biological, developmental, or social—as well as learned behaviors from their neighborhoods, social groups, and the prison system, could this contribute to the high recidivism rates among ex-convicts (Bartol & Bartol, 2021)?

Moreover, both combat veterans and former convicts might experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a higher level than those in society due to the trauma of institutionalization and the stress they endured while in these settings (American Psychiatric Association, 2025). While the life experiences of these two groups may differ, the process of becoming institutionalized in either environment increases the likelihood of issues such as drug abuse, violent tendencies, and antisocial behavior. This is because participation in such systems often requires individuals to suppress their individuality for the greater good of the institution. This lack of individuality can make it harder for them to adapt once released, potentially leading them back to crime as it may be the only environment they understand.

Another quote that helps us understand the need for change states: “Social voids like those created by deinstitutionalization must be filled; and with states deinstitutionalizing offenders, the toll is on their corresponding communities to address the needs of those offenders who are reentering after being incarcerated” (Frazier, Sung, Gideon, & Alfaro, 2015).

Both groups often develop a strong sense of belonging to the communities they were part of. While many combat veterans learn to cope with stress in healthy ways, convicts may become so indoctrinated by the criminal justice system that they are unable to reintegrate into society. If this happens, they might resort to committing crimes in an effort to return to the only environment they genuinely know.

It is also interesting to note that, in order to become a police officer, one must be at least 21 years old, while the minimum age to enlist in the military is typically 18 or even 17 with parental consent. The frontal lobe, which is responsible for decision-making and impulse control, continues to develop throughout these years. This suggests that society may prioritize younger individuals for law enforcement or military service roles because their brains are still developing and are, therefore, more malleable. Furthermore, an adolescent convict’s brain continues to develop up until they are around 25, meaning their development within the carceral system might be hindered by institutionalization.

These parallels are both intriguing and deserving of further exploration.

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2025). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., Text Revision). https://doi.org/10.5555/appi.books.9780890425787.x00pres

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2021). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach (12th ed.). Pearson.

Frazier, B. D., Sung, H.-E., Gideon, L., & Alfaro, K. S. (2015, May 6). The impact of prison deinstitutionalization on Community Treatment Services. Health & Justice. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5151559/

Trauma-Informed Care as Part of a Gender-Responsive Approach in Criminal Justice

The role of trauma and the way in which it is experienced within the criminal justice system is something we have explored throughout our course. I have found that you cannot talk about progressive changes and addressing needs in the criminal justice system without talking about trauma. This is especially true when thinking about the experiences of incarcerated women before, during, and after their involvement in the system. While trauma and mental health issues are pertinent to all incarcerated individuals, the unique experiences of women can go overlooked and current approaches for assessing risk and needs are informed by male normative standards (Hannah-Motaff, 2006). This means current approaches might fail to address the unique experiences and needs of women offenders which often involve trauma.

In my exploration of the benefits of trauma-informed and gender-responsive approaches for women, I found Bloom and Covington's Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Women Offenders (2008) to be incredibly informative and a clear call to action for incorporating trauma-informed care in the treatment of incarcerated women. As Bloom and Covington point out, female prisoners and jail inmates often have more mental health problems than male prisoners, with especially high levels of interpersonal trauma and experience with domestic violence. This is significant when we consider that incarcerated women might not be given resources and interventions that are designed to help them process and heal from trauma during their involvement in the criminal justice system (and after it). That being said, we can think of the gender-responsive approach as one that highlights the need for trauma-informed care and empowerment for incarcerated women.

I think when discussing trauma-informed care and gender-responsive approach, we should avoid presenting these as abstract concepts and instead be clear about how to practically apply these in the criminal justice system. I personally find Bloom and Covington's suggestions to be reasonable and helpful. They outline what a trauma-informed approach can look like: acknowledging women’s unique trauma histories, creating a safe, supportive environment that promotes healing, providing psychoeducation about trauma and abuse, teaching coping skills, and validating women’s reactions. I would add that fostering a culture of understanding and safety is crucial along with giving women autonomy in their treatment planning/goals, encouraging empowerment.

Trauma-informed and gender-responsive care requires comprehensive training of staff and the resources to hire quality mental health professionals. While this may require more funding, the potential positive outcomes from this approach are significant and justify the investment. Trauma-informed care is crucial for incarcerated women to meet the goal of reduced involvement with criminal activities (Bloom & Covington, 2008). Directly addressing traumatic victimization experiences, functional difficulties, and other mental health needs is a step toward rehabilitation and positive outcomes for incarcerated women. My takeaway here is that gender-responsive care for incarcerated women must be trauma-informed. This is done by creating a safe, supportive therapeutic environment that empowers women and promotes healing.

References:

Bloom, B. E., & Covington, S. S. (2008). Addressing the mental health needs of women offenders. In Women's mental health issues across the criminal justice system. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hannah‐Moffat, K. (2006). Pandora’s box: Risk/need and gender‐responsive corrections. Criminology & Public Policy, 5(1), 183–192.

Self-Care After Trauma

After experiencing trauma, self-care can be a vital step in regaining a sense of safety, and self, and not only comfort but help with managing stress during a time of healing. It is centered around taking steps toward feeling healthy and comfortable whether the trauma endured has been physical, mental, or both. Healing is a process.

It is important to know that trauma reactions are normal reactions in exceptionally abnormal situations (McNeilly, 2015). There is no typical reaction or required response after experiencing trauma. However, some reactions that can be experienced are emotional and psychological, cognitive, physical, and behavioral. By addressing these reactions we can establish ways to manage them while incorporating the self-care necessary for healing and recovery.

Physical, cognitive, and behavioral responses can manifest in numerous ways. Physically, a person can experience symptoms such as headaches, nausea or upset stomach, being easily startled, fatigue, high blood pressure, dizziness, rapid breathing, and insomnia. Cognitive responses include difficulty concentrating, flashbacks, amnesia, or worry. Finally, behavioral responses can be experienced as changes in sleeping and eating patterns, withdrawal from others, or not wanting to be alone (MITHealth, n.d.).

During a person’s recovery, they should be aware of their physical health. Being physically healthy can help support you through times when a person is feeling emotionally drained or recovering from physical injuries. Honesty with oneself and their support system is imperative to ensure that healing can happen.

In the physical sense, we can reflect on times when we did feel physically healthy. When doing so, we should address questions such as: how were sleep habits during this time? How were your eating habits, and what made you feel healthy, strong, or even comforted? Did you exercise? Did moving your body more make you feel better? Did you participate in previous self-care or daily routines that helped improve your day, start your day off well, or contribute to winding down in the evenings? (RAINN, n.d.).

By answering these questions, we can start to rebuild or take from the previous habits or routines and incorporate them into physical recovery by repeating or taking examples from these times. Furthermore, it is important to allow yourself to rest when you need to rest and do things that feel good to you.

Emotional self-care comes in many forms. It is not a one-size-fits-all routine, but as unique as the individual involved. By being able to recognize the signs of psychological and/or emotional distress we have a better chance of addressing them. These reactions can manifest in several ways such as fear, panic, or generally feeling unsafe, anxiety, flashbacks, anger, irritability, moodiness, crying, feelings of helplessness or meaninglessness, depression, violent fantasies, detachment, “survivor’s guilt” or self-blame, restlessness, over-excitability, hopelessness, and feelings of estrangement or isolation (MITHealth, n.d.).

Much like with our physical health, we can ask ourselves questions about times when our emotional health was in a better place. In doing so, we can reflect on how we can start trying to rebuild back to that place. Where did you spend your time? Who did you spend your time with? Did you feel safe and supported when you were with them? Where did you draw inspiration from during this time? Is there a particular book, quote, or even a Pinterest board where you put away things that made you feel good or happy? Did you like to meditate or journal? What did you like to do for fun? How did you relax? (RAINN, n.d.).

Being reminded of these times and these habits can help bring back into focus that there were times when the world wasn’t so overwhelming and there can still be those times again. Using the same habits from then can help work through the trauma a person has experienced by doing things they know have made them happy previously.

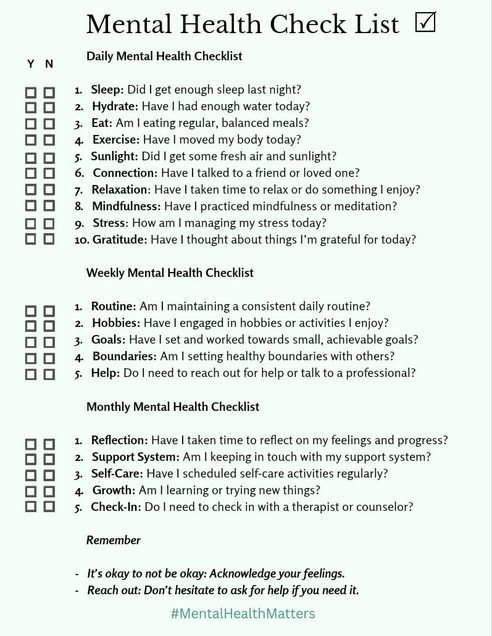

There are many types of self-care, emotional, financial, spiritual, professional and academic, mental, physical, environmental, recreational, and social (Reiff, 2024). Sometimes self-care, especially after trauma requires deliberate effort. This can be sleeping, showering, eating, watching television, reading, or going for a walk, as much as it is acknowledging the trauma, going to therapy, talking about the event with those you feel comfortable with, and learning your trauma triggers. You must allow yourself to feel your feelings. No matter what they are your feelings are valid and you are allowed to feel however you want to about what happened to you.

If you are feeling unsure of how to start practicing self-care, here are a few lists of ideas for you:

References:

McNeilly, C. (2015, September 23). Taking Care of Yourself After a Traumatic Event | University Counseling Service - The University of Iowa. Counseling.uiowa.edu.

https://counseling.uiowa.edu/news/2015/09/taking-care-yourself-after-traumatic-event

FAQ: Common Reactions to Traumatic Events | MIT Health. (n.d.). Health.mit.edu. https://health.mit.edu/faqs/mental-health/common-reactions-to-traumatic-events

Self-Care After Trauma | RAINN. (n.d.). Rainn.org. https://rainn.org/articles/self-care-after-trauma

Reiff, L. (2024). 9 Types of Self-Care & How to Practice. ChoosingTherapy.com.

https://www.choosingtherapy.com/types-of-self-care/

Girlspring. (2020, March 28). Self-Care Check List! - GirlSpring. GirlSpring.

https://girlspring.com/self-care-check-list/

TheMindsetGarden. (2024, July). Benefits of a Mental Health Checklist. Payhip.

https://payhip.com/TheMindsetGarden/blog/mindset/benefits-of-a-mental-health-checklist

Teachers’ Secondary Stress and Trauma After School Shootings

Recently we were asked to explore the different typologies and characteristics of multiple murderers. Within this context, the characteristics of school shooters were also explored. According to Bartol & Bartol (2021), school shootings are not a common occurrence; however, in my opinion, they are far too common. There is no other country that experiences as many school shootings as the United States (Bartol & Bartol, 2021). In 2024, there were 39 school shootings that resulted in injury or death. At least one school shooting happened each month in 2024 (Lieberman, 2024). In my opinion, these numbers are astounding.

Bartol & Bartol also revealed that when school shootings do occur “…they generally involve one perpetrator who shoots a small number of victims and is promptly taken down…(Bartol & Bartol, p. 358). In a recent class discussion, I expressed my concern about this quote. As an educator in an urban public high school, this assertion deeply struck me. What is the definition of “victim” in this context? Is victim defined here as those who died during the commission of murders? Care should be taken to acknowledge those who may not have died or been physically wounded, but will experience lifelong psychological trauma as a result of being present during the tragedy. Parents, families, and friends of those who were injured or killed; students and teachers who were present during the shootings; students and teachers in cities, states, and countries outside of where the incident occurred – these individuals are also victims.

I am one such victim. I was never able to put a name to it, but after reading Dr. Rousseau’s lecture on secondary trauma, I was relieved by the clarity it provided. While I am privileged to have never been embroiled in a school shooting, each time I hear about a school shooting, I am devastated. When these tragedies occur, there is little to no support provided for teachers in my school building, which seems to be a commonality among other districts as well. For instance, after the Sandy Hook murders, teachers who experienced secondary trauma were not offered support by their schools’ administration. (Dixon, 2014). The day following the Abundant Life Christian School shooting, I overhead a student talking about making a bomb. I immediately reported him to school counseling and he returned to class less than 5 minutes later.

It is difficult for me to walk into my school building each day knowing that is not equipped with metal detectors. District leaders’ theories regarding the effects of metal detectors on teacher and student morale, especially in a community that serves mostly Black and Latino students, deters the installation of what I consider such a necessary tool (Jenkins, 2024). It is difficult to acknowledge the pervading fact that a student can enter the school with a weapon – undetected – and the incessant worry of tragedy striking my school. The implementation of safe mode drills, which are designed to prepare students and staff in the event an active shooter is on campus, only adds to the trauma experienced in a space that is supposed to feel welcoming and safe. Additionally, due to the unpredictable nature of school shootings(Bartol & Bartol, 2021), I do not believe the implementation of these drills effectively prepares students and school staff. My hope is that broader consideration will be given to all victims who suffer from school shooting related trauma and everyone involved receives the necessary supports to live better and more productive lives.