A pandemic inside a pandemic

Gender violence against women is one of the clearest manifestations of the subordination, inequality and power relations of men over women; this violence is caused by the difference between the two genders; in other words, women suffer violence simply because they are women, regardless of their social status, economic or cultural level.

Some types of this type of violence are the following:

- Psychological: this type of violence has as its main contexts the home, partner or family, however, it does not have to reach harassment or humiliation, but can manifest itself as restriction, manipulation or isolation, which causes emotional and psychological damage, harming the development of a woman.

- Physical: is any type of action that causes suffering or physical harm, affecting integrity. For example, a blow, a push, etcetera.

- Sexual: refers to any action that violates or threatens a woman’s right to decide about her sexuality and includes any type of sexual contact without consent.

- Economic: corresponds to actions (direct or through the law) that seek a loss of patrimonial/economic resources through limitation. An example of this is that women cannot own property or use their money or property rights.

- Work: women’s access to positions of responsibility in the workplace is hindered, or their development or stability in a company is complicated by the fact that they are women.

- Institutional: authorities or officials complicate, delay or prevent access to public life, adherence to certain policies or even the possibility for women to exercise their rights.

Unfortunately, nationally it is estimated that “approximately 94 percent of crimes committed against women go unreported” (Mata, 2019). Of the total number of women who were assaulted, only 4% filed a complaint or filed a report with an authority and 2% only sought help from an institution. Among the reasons why women do not report their aggressors are the following:

- They considered that it was something unimportant that did not affect them.

- Shame

- Fear of threats or consequences

- She thought they would not believe her or that they would say it was her fault.

- Did not know how and where to report

- The aggressor was someone influential or with a certain amount of power

Gender violence in Mexico has been invisibilized for many years and only about 5 years ago began to have the visibility it deserves, all thanks to the participation of feminist collectives and various non-governmental groups which focus on supporting the population at risk.

However, with the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in all parts of the world, women were indirectly forced by the government to remain locked in quarantine with their aggressor, which raised the levels of gender violence that were already high. COVID-19 highlighted the lack of government action and inefficiency in terms of health and protection for women suffering violence in any sphere.

Data show that the confinement derived from covid-19 led to the records of violence against women in the home to increase 60% in Mexico, according to figures from the United Nations (UN).

From January to May 2020, data given from the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System, showed that during the confinement there was 375 alleged victims of femicide and 1,233 female victims of intentional homicide were registered, giving a total of 1,608; that is, 6% more than in the same period of 2019.

Likewise, during the same year, 23,460 alleged female victims of intentional injuries were counted and 108,778 emergency calls to the 911 number, related to incidents of violence against women had been attended.

The COVID-19 emergency is deepening gender gaps and inequalities that already existed and were ignored, as well as increasing the risk of violence for millions of women in Mexico. Latin America is considered the most violent region worldwide, this is largely due to the prevailing patriarchal culture that governs all customs and practices of daily life, leading to the naturalization of violence against women, the production of stereotypes, and the perpetuation and reproduction of discrimination (Moreno and Pardo, 2018).

Emotional abuse, such as insults, humiliation, and threats, are also a widespread phenomenon in Latin American countries. Many women reported that their last or current partner used three or more controlling behaviors, including isolating them from their families and/or friends, insisting on knowing their location at all times, and limiting their contact with family and/or friends (Bott, et al. 2012).

In Mexico, a large proportion of violent deaths of women are femicide murders where the victims are attacked because of the social condition of their gender. This terrible trend is on the rise: from seven violent murders of women per day two years ago, there are currently 10, according to the UN Women Office in Mexico (Villegas and Malkin, 2019). These data refer only to the most serious type of gender-based violence; however, other dimensions of this phenomenon are also highly present in the country, among which one of the most worrisome is domestic violence.

In response to the announcement of the Jornada Nacional de Sana Distancia, several civil organizations declared that measures should be adopted to guarantee women’s access to a life free of violence during the current health crisis, and also demanded to ensure that policies aimed at combating gender violence are not neglected as a result of the readjustment of priorities. In particular, Amnesty International, the National Network of Shelters and X Justicia for Women highlighted the need to:

- ensure the provision of resources to shelters,

- guarantee the functioning of the justice centers,

- guarantee access to justice for this sector of the population.

In this context, domestic violence has proven to be one of the most worrisome issues. Almost two months after the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Mexico, the Shelter Network observed an increase of 5% in women’s admissions and 60% in cases of counseling via telephone, social networks and email. In addition, the integrated National Refugee Red centers are already at 80% or 110% of their capacity, especially in entities such as Guanajuato, State of Mexico and Chiapas (Castellanos, 2020).

It must be recognized that Mexico faces a double contingency consisting of a crisis due to gender violence and the expansion of COVID-19, and that both require the same level of attention. As of April 21, 100 women have died from the coronavirus since it entered Mexico on February 28, while in the same period 367 women have been killed (Global Health 5050, 2020; Castellanos, 2020).

The normalization of violence against women, as well as other gender-based inequalities, is unfortunately a persistent phenomenon. If we want to make this problem visible in the context of a pandemic, it is essential to take optimal and strategic measures immediately.

As a result, I began to develop an app to provide support to women who need help and receive it in an effective and efficient way without putting them at risk and at the same time eliminate the black number of complaints.

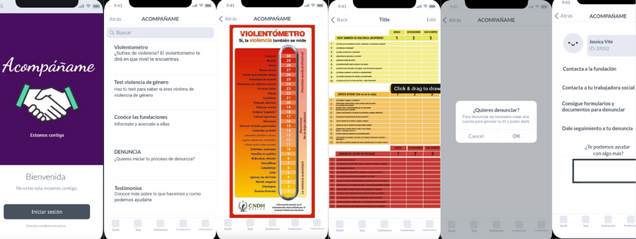

In collaboration with Casa Luna, a network of shelters in the Cuauhtémoc district of Mexico City, X Justicia and a network of colleagues from the university, I created the ACOMPÁÑAME application, which is a tool that facilitates women to receive psychological and physical help, as well as legal assistance and if necessary the opportunity to settle in a shelter, always taking into account their welfare in a comprehensive manner.

The app consists of first taking a test to find out if they are suffering violence and identify what type of violence it is in order to proceed in a better way. After that, women will have the option to contact specialized doctors to receive either physical or psychological treatment and as a final point they will be able to contact a network of lawyers to proceed legally against their aggressor.

This last point and the medical one are extremely sensitive points because of the information that is collected at the moment of contacting the victim, that is why all the data is treated with the utmost confidentiality giving the victim a folio number which also serves to prevent her aggressor from suspecting that something is going on. Both legal and medical actions being taken are given a film name so as not to raise suspicions and so that the victim is not at risk of further violence.

The pandemic created by COVID-19 came to an end, with the arrival of vaccines and movements of the different governments around the world; however, the pandemic of gender violence is far from coming to an end. It is necessary for each and every one of us to take action on this issue because, although it sounds cliché, the next woman who may suffer violence could be your mother, your sister or your daughter.

Initial layout of the app

References:

Mata, M. (2019). Cifra negra, 94% de delitos contra mujeres: JAPEM [Sitio web]. Retrieved may 2nd, 2023, from https://www.milenio.com/policia/cifra-negra-94-delitos-mujeres-japem

Inmujer. (2016). Definición de violencia de género [Sitio web]. Retrieved may 2nd, 2023, from http://www.inmujer.gob.es/servRecursos/formacion/Pymes/docs/Introduccion/02_Definicion_de_violencia_de_genero.pdf

Foreign affairs. (2020).La violencia contra las mujeres en Latinoamérica. Retrieved May 2nd, 2023. https://revistafal.com/la-violencia-contra-las-mujeres-en-latinoamerica/

New york times. (2019). ‘Not My Fault’: Women in Mexico Fight Back Against Violence. Retrieved May 2nd, 2023.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/26/world/americas/mexico-women-domestic-violence-femicide.html

Organización Panamericana de la Salud. (2020). Violencia contra las mujeres. Retrieved May 2nd, 2023.

International Center for Research on Women. (N/D). The Sex, Gender and COVID-19 Project. Retrieved May 2nd, 2023.

https://globalhealth5050.org/the-sex-gender-and-covid-19-project/