Home

Treating vs. Curing

When trauma is commonly thought of most would expect that it results from war or other instances involving numerous encounters of overwhelming stress. Although these instances certainly pose a significant risk of trauma, trauma can be more easily obtained by numerous different types of events and is encountered frequently on a regular basis. About 6 out of every 10 males and 5 out of every 10 females will face trauma at least once some point in their lives (National Center for PTSD). In addition to that, about 7 to 8 percent of the population will have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at some point during their lives (National Center for PTSD). Trauma is defined as “an emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, rape or natural disaster.” (American Psychological Association). Due to the ability of trauma to affect so many people not only in the U.S. but worldwide it is important to understand neurobiology and the effects such events have on the brain. Understanding the neurobiology of trauma is a must for treating such trauma medically and will aid in teaching coping methods to those suffering from these traumatic events. With that being said, the developed understanding of the neurology seems to successfully identify the parts of the brain that are stimulated and associated to disorders relating to trauma yet medicine fails to permanently cure the issue and only keeps those under balance while on the medication. Considering that a lack of medicine can leave one defenseless if not taken or forgotten should medicine be an approved or considered a reliable form of treatment to trauma?

“When someone experiences a traumatic event or experiences extreme fear, brain chemistry is altered and the brain begins to function differently--this is called the "Fear Circuity" and it is a protective mechanism which we all have inside of us.” (University of Northern Colorado). Knowing that a traumatic event can alter the brains chemistry leaves an open door within neurobiology to examine and treat the lasting effects. “Sertraline and paroxetine are the only antidepressants approved by the FDA for the treatment of PTSD” (Alexander, 2012). To this date there is no known permanent treatment of PTSD by prescription drugs and all are needed to be taken regularly and prescribed a dosage. Medications work by altering neurotransmitter production and transmission (Rousseau, 2021). However, other methods like yoga “can help to redirect the firing of neurons, or even create new neurons through two processes, called neuroplasticity and neurogenesis.” (Rousseau, 2021). Suicide rates of those dealing with PTSD is as much as thirteen times as many as those not dealing with PTSD (Gradus, 2017). Since a medical form of treatment cannot be relied on if they are not obtainable at all times it poses a clear significant risk to those dealing with PTSD. As pointed out in the film “Healing a Soldier’s Heart” there have been over 110,000 suicides since the Vietnam war which is almost twice as many casualties during the war of 58,000 (Healing a Soldier’s Heart, 2013). With this in mind, unless a more sustainable one time treatment becomes an option, teaching coping techniques should be more of a recommended form of treatment.

Of course there are extreme cases where teaching coping methods are not sufficient enough and the use of medication is needed to support the healing process. The message here is not to discredit current medications but to raise the concerns on its reliability and support future alternative methods that provides more of a cure than a temporary fix.

Works Cited

Alexander, W. (2012, January). Pharmacotherapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder In Combat Veterans: Focus on Antidepressants and Atypical Antipsychotic Agents. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3278188/

Gradus, J. (2017). PTSD and Death from Suicide. Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V28N4.pdf

Neurobiology of Trauma. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.unco.edu/assault-survivors-advocacy-program/learn_more/neurobiology_of_trauma.aspx

Olsson Stephen, & Cultural & Educational Media (Producers), & Stephen, O. (Director). (2013). Healing a Soldier's Heart. [Video/DVD] The Video Project. https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/healing-a-soldier-s-heart

Rousseau, D. (2021). CJ 720 Module 1. Boston University. https://learn.bu.edu/ultra/courses/_75565_1/cl/outline

Trauma and Shock. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma

VA.gov: Veterans Affairs. (2018, September 13). Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp

Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder: Diverging Responses to Neglect

This post is for Kelly Godwin

Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder: Diverging Responses to Neglect

While childhood trauma can consist of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, one of the most common reports received by child protective services is neglect. Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED) are the result of this maltreatment and can prove to be a long-term detriment to the social, emotional, and intellectual development of affected children. (Kroupina, et al. 2018). Children diagnosed with either of these attachment disorders did not have their basic emotional needs met in early life, but the symptoms of the disorders are very different. (Kroupina, et al. 2018).

The delineation between social inhibition (RAD) and social disinhibition (DSED) is a fairly recent development, as before they were viewed under the umbrella of attachment disorders in the DSM-IV but were reclassified with these differences in mind upon the release of the DSM-V. (Kliewer-Neumann, et al. 2018). RAD is observed as social inhibition and occurs when a child’s need for stimulation, comfort and soothing are not met. (Humphries, et al. 2017). This results in a failure to seek or respond to comfort, hypervigilance, becoming emotionally withdrawn and indifference to caregivers. (Kliewer-Neumann, et al. 2018). (Kroupina, et al. 2018). In contrast, children with DSED experience similar forms of neglect, but instead exhibit signs of being extremely social, overly friendly, and fail to acknowledge normal social boundaries. (Kroupina, et al. 2018). Children with either RAD or DSED may exhibit symptoms of inattentiveness and hyperactivity which may affect academic achievement. (Humphreys, et al. 2017).

These attachment disorders fall on spectrum, meaning these disorders share multiple linked conditions with diverse symptoms and degrees of severity. Great strides have been made in diagnosing attachment disorders in the last 20 years as clinicians use situational observation and interviews or questionnaires. (Kliewer-Neumann, et al. 2018). Observations used to test for attachment behavior are based in having the infant or child interact with a stranger to see if the child is responsive to the stranger or caregiver, and in cases of older children, whether the child will willingly go off with a stranger. (Kliewer-Neumann, et al. 2018). The interview most often used is the Disturbance of Attachment Interview which asks caregivers about their observations of specific behaviors exhibited by the child and frequency to determine if the child shows either inhibited or disinhibited characteristics. (Kroupina, et al. 2018).

Because neglect is one of the most reported forms of child maltreatment, foster children tend to show observable signs of these disorders, however being placed with responsive caregivers can help resolve the issues related to RAD and DSED. (Kliewer-Neumann, et al. 2018). The positive impact of responsive caregivers is especially effective when maintained over an extended period and if the duration of neglect is shorter. (Kroupina, et al. 2018). Children with DSED exhibited improved signs of recovery if placed with effective caregivers at a younger age. (Humphreys, et al. 2017). Children coming from high-risk environments such as lengthy hospitalization, institutionalization, and foster care environments where placement is not consistent need to be referred to well-trained clinicians to help them avoid the long-term effects of RAD and DSED. (Kroupina, et al. 2018). (Humphreys, et al. 2017). In all cases, the most important means to address signs of attachment disorders is to ensure the child has a caregiver who is responsive to the child’s emotional needs as early as possible. (Humphreys, et al. 2017). Children exhibit a natural resilience and can develop secure attachments when put in healthy environments. (Humphreys, et al. 2017).

Works Cited:

Humphreys, K., Nelson, C., Fox, N., & Zeanah, C. (2017). Signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at age 12 years: Effects of institutional care history and high-quality foster care. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2), 675-684. doi:10.1017/S095457941700025

Kliewer-Neumann, J.D., Zimmermann, J., Bovenschen, I. et al. (2018). Assessment of attachment disorder symptoms in foster children: comparing diagnostic assessment tools. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 12, 43 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-018-0250-3

Kroupina, M., Ng, R., Dahl, C., Nakitendi, A., Ellison, K. C.. (2018). Identifying Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder in a Sample of High Risk Children. (https://bettercarenetwork.org/sites/default/files/RAD%20and%20DSED.pdf)

Restitution and Victims of Child Exploitation

Years ago, while working as an analyst processing evidence in child exploitation cases, I met a victim of one of the most widely circulated child pornography series to date. While the abuse occurred when the victim was ten and eleven, I met her right before she started college, after her fugitive father was arrested and finally prosecuted for his crimes. She recounted how the abuse was traumatizing enough, but later discovering her father traded images and videos of the abuse online was almost too much to bear. She also discussed the long-term implications from that knowledge, fearful that every person she encountered might recognize her from those images of the worst moments of her life. Knowing that so many individuals took pleasure in her pain was also something she couldn’t comprehend. Meeting her was surreal, as I viewed images of her abuse in nearly every case I examined, and I could not even fathom what she had experienced in her young life. This encounter was almost 15 years ago, and it still has a great impact on me, and I am devastated for her (and all victims of this sort of crime) that those images are probably still being circulated every day, with the victim never being able to escape the daily reminder of the abuse.

Although I am no longer certain if this is the norm, when I worked in that field, it was a requirement that the identified victim of child exploitation be notified every time their image appeared in a case, with some victims potentially notified multiple times a day, every day of the week, due to the frequency their images were traded. While I understand the intent behind this requirement, in reality, it meant the victim faced a constant reminder of the abuse, impeding their ability to move forward. Due to this reason, some of the victims assigned an intermediary to receive the notifications, as they could not handle the constant influx of notices.

Assisting victims of crime and trauma is a challenging situation, as there is no way to erase the impact of what happened to them. “Trauma impacts the individual, his or her relationship with family and friends, his or her ability to hold jobs, and the way he or she interact with the world around him or her. It can change life paths, alter personal abilities, and cause physical and neurological damage that may or may not be repaired” (Rousseau, 2021, p. 8). Every person handles trauma differently, and every case is different, with some offenders penalized to the maximum extent of the law, while others get no penalty. The concept of restitution continues to be brought up when discussing victims of crime, although there are advocates both for and against employing monetary compensation for crime victims. "Restitution means restoring someone to the position occupied before a particular event took place,” while the “purpose of restitution is to make a victim whole” (Boe, 2010, p. 210). Forcing an offender “to pay a monetary fine, often in addition to serving a prison sentence, forces an individual defendant to address the harm his crime has caused to the individual victims of his crime and to society. Victims, especially victims of child pornography, frequently suffer both financial and emotional losses because they have to seek counseling or medical services for the rest of their lives” (Boe, 2010, p. 211). While money will never make a crime victim “whole” again, and will never be able to “restore” them to the person they were prior to the traumatic event, monetary compensation can help alleviate some of the financial hurdles they may face with seeking treatment or account for some of the financial losses they may have incurred due to their trauma.

However, one challenge surrounding restitution is assigning a financial sum commensurate to the impact on the victim, which is seemingly impossible, as the full impact can never fully be accounted. “Knowing that thousands of individuals possess images and video of oneself being raped and sexually abused in humiliating fashion can inflict deep, life-lasting trauma that extends well beyond the initial sexual abuse. This emotional trauma results in economic burdens,” including psychological counseling costs and lost income (Cassell et al., 2013, p. 73). Additionally, “determining each victim's losses requires a careful analysis of how each victim's life is impacted by child pornography,” which includes economic, emotional and physical losses, with restitution payments providing “not only psychological counseling, but also vocational and educational training to move forward with their lives” (Cassell et al., 2013, p. 74).

While I don’t have any concrete ideas regarding a “just” way to compensate various victims of crime, I do think some sort of financial reimbursement is warranted to cover some of the long-term medical, legal and therapeutic expenses, which can accumulate quickly. An additional challenge also arises when trying to recoup money for the crime victim, especially if the offender has no financial means to repay the victim. A victims’ compensation fund has been discussed, as have many other ideas, but the practical enforcement of restitution might also impact a victim long-term, if they are additionally traumatized by the justice system. Overall, I find the idea of restitution a fascinating and relevant topic concerning crime victims and the impact of trauma, although there is no easy solution when figuring out how to implement it. For me, meeting the victim was a huge reminder that we never know what anyone else has gone through or is currently going through, as looking at her on the surface, no one would have ever guessed what she was battling under the surface. Overall, it reminded me that when discussing some of these issues regarding restitution, or punishment or rehabilitation, a real-life victim is on the other end, and the human impact element is always the one that needs top consideration.

References

Boe, A. B. (2010). Putting price on child porn: Requiring defendants who possess child pornography images to pay restitution to child pornography victims. North Dakota Law Review, 86(1), 205-230.

Cassell, P. G., Marsha, J. R., and Christiansen, J. M. (2013). The Case for Full Restitution for Child Pornography Victims. George Washington Law Review, 82(61), 61-110.

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 1 Study Guide [Notes]. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Traumatic Experiences in Correctional Facilities: Who Has it Worse? Correctional Staff or Those who are Incarcerated

Traumatic Experiences in Correctional Facilities: Who Has it Worse? Correctional Staff or Those who are Incarcerated

When thinking of what it would be like to be incarcerated, the lay person can base their perception on any number of popular televisions shows or movies; abusive staff, gangs, stabbings, rapes and a pervasive culture of violence. While these things do occur, in some facilities much more than others, many short term, low custody sentences may not experience these things firsthand. However, the constant fear of the above referenced items coupled with poor (if not disgusting) food quality, strip searches, group showers, unsanitary conditions, lack of access to family/friends, lack of sleep due to keys, doors, and cell checks, and reduced/delayed access to medical and mental health may in fact lead to greater negative emotions and trauma. Any piece or combination thereof can lead to PTSD upon release back into society. In addition, “Other factors are interwoven into the pathogenesis of this condition, including the many risk factors that underlie the behavioral and thought patterns of many criminals. These include childhood traumas such as extreme poverty, child abuse by their parents or caregivers, experiences of neglect, physical and sexual abuse, as well as other forms of mistreatment” (Thomas, 2019).

According to various research projects:

- Even before entering a prison or jail, incarcerated people are more likely than those on the outside to have experiencedabuse and trauma (Thomas, L, 2019).

- An extensive 2014 studyfound that 30% to 60% of men in state prisons had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), compared to 3% to 6% of the general male population (Wolff, N, et al, 2014).

- 7% of womenin state prisons experienced childhood abuse, compared to 12 to 17% of all adult women in the U.S.. (BJA, 1999).

The below chart is from the Prison Policy Initiative article titled No escape: The trauma of witnessing violence in Prison:

| Estimating the prevalence of violence in prisons and jails | ||||

| Reported incidents and estimates | ||||

| Indicator of violence | State prisons | Federal prisons | County jails | Source |

| Deaths by suicide in correctional facility | 255 deaths in 2016 | 333 deaths in 2016 | Mortality in State and Federal Prisons, 2001-2016; Mortality in Local Jails, 2000-2016 | |

| Deaths by homicide in correctional facility | 95 deaths in 2016 | 31 deaths in 2016 | ||

| “Intentionally injured” by staff or other incarcerated person since admission to prison | 14.8% of incarcerated people in 2004 | 8.3% of incarcerated people in 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2004 | |

| “Staff-on-inmate assaults” | 21% of incarcerated men were assaulted by staff over 6 months in 2005 | Wolff & Shi, 2010 | ||

| “Inmate-on-inmate assaults” | 26,396 assaults in 2005 | Census of State and Federal Adult Correctional Facilities, 2005 | ||

| Incidents of sexual victimization of incarcerated people (perpetrated by staff and incarcerated people) | 16,940 reported incidents in 2015 | 740 reported incidents in 2015 | 5,809 reported incidents in 2015 | Survey of Sexual Victimization, 2015 |

| 1,473 substantiated incidents in state and federal prisons and local jails in 2015 | ||||

The above charts and studies, however, only examined the effects of correctional environments on those who were incarcerated inside by judicial order and did not consider those who work inside the facilities, often for long and mandated shifts. Not as many studies could be found on correctional staff related trauma. But trauma and stress amongst staff can easily be imagined: reviewing horrific case files; witnessing traumatic events; mandatory overtime; role ambiguity; and constant disrespect by the inmate population. “According to a 2015 article by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, correctional employees experience higher rates of stress-related illnesses that contribute to low levels of job satisfaction, which has been linked to burnout and is thought to lead to compassion fatigue” (Pittaro, M., 2020).

In addition, a study conducted and published this year found that correctional officers self-reported significantly higher exposure to potentially psychologically traumatic events than other medical and wellness workers. Moreover, correctional staff also self-reported greater rates of symptoms of mental disorders, including PTSD, social anxiety, panic disorder, and depression, among others (Fusco, N., et al, 2021).

Based on the above referenced data and numerous additional uncited studies, it is evident from the research and probably obvious to the average law abiding civilian, that both correctional staff and inmates are exposed to the unimaginable and unfathomable behind the walls. Typically, opposing sides prevent the evolution and availability of growth for each of these populations: those who may believe that inmates deserve this and should not be afforded anything when being punished and those that may feel that correctional staff are tough and know what they sign up for. Acknowledging the equality in the two groups and making available trauma informed approaches to care for the inmate populations and programming for self-care for staff is critical to reduce these numbers and ensure smooth transitions for each in society. The truth is, that nearly all inmates will one day be released into society and, in addition, will be existing with us. Moreover, staff as well are living amongst us, on their often-limited time off, and should as well be able to ‘leave it at the gate’ in terms of their work stressors. To that note, similarly, one a sentence and work shift is complete, any individual should be, and we should want them to be, functioning, healthy and productive members of the society in which we all live.

References:

Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA). 1999. Prior Abuse Reported by Inmates and Probationers. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/parip.pdf.

Fusco, N., Ricciardello, Jamshidi, Carleton, Barnim and Hilton. (February 15, 2021). When Our Work Hits Home: Trauma and Mental Disorders in Correctional Officers and Other Correctional Workers. National Institutes of Health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7917131/.

Pittaro, Michael. March 24, 2020). Correctional Officers and Compassion Fatigue. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/au/blog/the-crime-and-justice-doctor/202003/correctional-officers-and-compassion-fatigue.

Thomas, Dr. Liji. (February 27, 2019). Prisoner Post Traumatic Stress. Medical Life Sciences News. https://www.news-medical.net/health/Prisoner-Post-Traumatic-Stress.aspx.

Widra, Emily. (December 2, 2020). No escape: The trauma of witnessing violence in Prison. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/12/02/witnessing-prison-violence/#lf-fnref:1.

Trauma Informed Policing by Frederick Morse

In recent years perhaps no profession has received as much scrutiny as law enforcement. Americans are redefining social norms and expecting more professionalism and accountability from law enforcement. One of the areas in law enforcement that has been beneficial, yet not without growing pains, has been the proliferation of body-worn video cameras. An additional facet of American life that has also received a fair amount of attention is trauma and mental illness. Research has shown that early childhood trauma can result in hindered growth resulting in uncontrolled anger, inappropriate behavior, disregard for rules, and drug or alcohol abuse (Rousseau, 2021). These precursors often result in contacts with law enforcement.

In the United States, a growing number of service requests for law enforcement similarly involve police interaction with vulnerable individuals or those experiencing a psychologically based crisis. A recent study in Scotland revealed that approximately 80% of all calls for service for law enforcement were non-criminal in nature (Gillespie-Smith, 2020).

With this dynamic in mind, scholars in Scotland conducted research where they exposed police personnel to trauma informed practices. Specifically, the study chose one police division and showed them the documentary “Resilience: The Body of Stress and Science of Hope.” The documentary explained how chronic stress releases hormones within the body of children which then results in dysfunction in the minds and bodies of youth. After viewing the film, the police personnel were given an overview of the 1998 Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study and scores. There was a panel of experts available for questions and to provide further context for the data.

Police personnel learned that in Wales, individuals with an ACE score of four or more were twenty times more likely to be incarcerated at some point in their life than the general public (Bellis, 2015). Similarly, the officers learned that approximately 89% of the prisoners in Wales reported at least one ACE (Gillespie-Smith, 2020). Police personnel who received the trauma informed training were then questioned as to their attitudes and understanding about suspects, witnesses, and victims. The researchers then compared the answers with answers from officers from another police division that did not receive the trauma informed policing training. The answers were not significantly different (Gillespie-Smith, 2020). Many of the officers who received the training expressed confusion about the ACE score research. The officers indicated that the trauma had occurred before their involvement and they failed to see how the new knowledge could benefit their current role. This was a common theme in the feedback from the participants (Gillespie-Smith, 2020).

On its face, the scholarly work in Scotland appeared to be unremarkable. However, if law enforcement agencies in the United States could build upon this trauma informed approach to policing and combine it with the technology of body worn video, real progress could be made. Law enforcement personnel have countless contacts and calls for service with individuals with mental health needs. A trauma informed approach to these calls for service could curtail any use of force and would result in decreasing further trauma to the individual in crisis or the officer.

Law enforcement administrators need to seek out strategies for improved professionalism and techniques for de-escalation. With the use of body worn video, contacts with individuals in crisis or mental health decompensation can be reviewed by law enforcement trainers and mental health professionals to improve officer responses and protocols. All contacts with citizens with mental health needs would be given a unique computerized clearance code making it easier to identify and retrieve the incidents for later review. The review of body worn video would be for educational purposes only, with the goal of improving trauma informed practices for law enforcement personnel. Police agencies could generate training videos from body worn video footage from actual interactions. The videos would include instructional narratives from mental health professionals and would be disseminated to other stations and personnel. A secondary objective would be to ensure that law enforcement personnel are getting the necessary and timely assistance from mental health agencies. If both agencies can work in a collaborative manner, individuals in crisis might receive professional intervention and proper care instead of a trip to the county jail.

Submitted by: Frederick Morse

Works Cited

Bellis, M. A. (2015). Adverse Childhood Experiences and their Impact on Health-Harming Behaviours in the Welsh Population. Wales: Cardiff: Public Health.

Gillespie-smith, K. B. (2020, August). Moving Towards Trauma-Informed Policing: An Exploration of Police Officer's Attitudes and Perceptions Toward Adverse Childhood Experinces (ACEs). Retrieved from https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/en/publications/moving-towards-trauma-informed-policing-an-exploration-of-police-#:~:text=In%202018%20Ayrshire%20Division%20of%20Police%20Scotland%20announced,perceptions%20and%20attitudes%20towards%20becoming%20a%20trauma-in

Rousseau, D. (2021). Trauma and Crisis Intervention. Module 2 Study Guide. Boston University.

Is Art Therapy a Legitimate Form of Treatment?

According to the American Art Therapy Association, art therapy can be defined as a mental health and human service aimed at engaging the mind, body, and spirit through visual and symbolic expression. The goal of this therapy is to empower individuals, communities, and society by giving a voice to experience through this visual/symbolic expression. It is used to, "increase cognitive and sensorimotor functions, foster self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivate emotional resilience, promote insight, enhance social skills, reduce and resolve conflicts and distress, and advance societal and ecological change." Art therapy is administered through master-level clinicians at schools, prisons, hospitals, psychiatric and rehabilitation facilities, senior centers, etc. to treat people with medical and mental health problems, and those in search of emotional, creative, or spiritual growth (American Art Therapy Association , 2017).

It may just be me, but I feel like compared to other mental health practitioners, Art Therapists may be looked down on. When you hear the term "Art Therapist", you may think that the job is a walk in the park or just a chaperone coloring with kids. That could not be further from the truth. Art Therapist's go through an extensive amount of schooling and training in order to give the patients the quality and therapeutic care that they need. To become an Art Therapist, a master's degree is needed for ENTRY LEVEL in the field with coursework including: training in the creative process, psychological development, group therapy, art therapy assessment, psychodiagnostics, research methods, and multicultural diversity competence. Upon completion of graduate school, the future therapist must become board certified through the Art Therapy Credentials Board. To accompany that, therapists must complete 100 hours of supervised work along with 600 hours of a clinical internship. I know what you are all thinking and no, the Art Therapy Association does not consider an adult coloring book a form of therapy because it is not administered by a licensed Art Therapist (American Art Therapy Association , 2017). With that being said, they do not discourage the use of one. Would you trust an Art Therapist for you or a loved ones counseling needs?

Below I have attached a video of Donna Betts, PhD, ATR-BC explaining how art therapy is administered to people with Autism Spectrum Disorder:

When it comes to clinical effectiveness of art therapy in all sorts of patients, multiple studies have been done and yield interesting results. When it comes to those with depression, in nine studies it was found that art therapy significantly reduced depression in six of those cases. In seven studies examining anxiety, six of those studies showed a strong decrease in anxiety. In the three studies addressing trauma, all of them showed a reduction of trauma symptoms. In the one study examining cognition, the control group showed significant improvements in cognitive function relative to the art therapy group. Finally, when it comes to distress, the three groups all were found to show a reduced amount of distress (Uttley, 2015). There is a lot of research out there proving the benefits of art therapy in all sorts of realms. With this being the case you would think that art therapy would be offered as a practice more than it is. Even though personally I am not a very talented artist, I feel as if looking at art and its beauty is an instant mood elevator. Regardless of your artistic ability, would you be interested in trying art therapy?

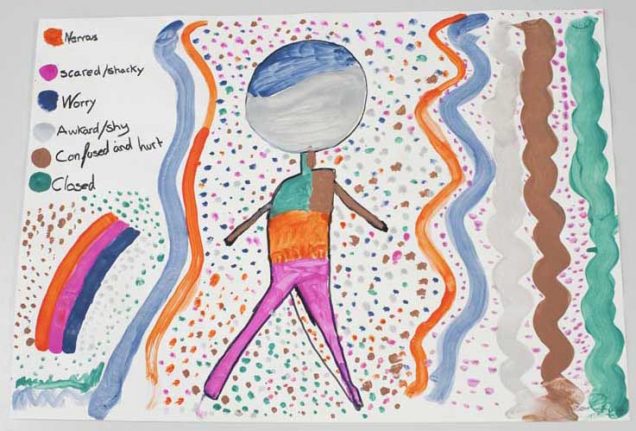

Art work done by sexual abuse survivor "Maxine" when asked to draw how she feels emotionally on a daily basis (The Palmeira Practice, 2018).

References:

About Art Therapy. American Art Therapy Association. (2017). https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/

Art Therapy in Action. American Art Therapy Association. (2017). https://arttherapy.org/art-therapy-action/

The Palmeira Practice | Brighton & Hove Counselling. (2018, February 23). Working with sexual abuse in art therapy - The Palmeira Practice: Brighton & Hove Counselling. The Palmeira Practice | Brighton & Hove Counselling. https://www.thepalmeirapractice.org.uk/expertise/2018/2/22/working-with-sexual-abuse-in-art-therapy.

Uttley, L. (2015, March). Clinical effectiveness of art therapy: quantitative systematic review. Systematic review and economic modelling of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of art therapy among people with non-psychotic mental health disorders.

Liquid Trauma Treatment and Law Enforcement

For most professionals, when colleagues ask to grab a few drinks after work, this is seen as a friendly gesture to build relationships at the workplace. For law enforcement this can be seen and used as a way to cope with the stress and trauma from the job or to self medicate for anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder. While the exact number is hard to calculate, it is estimated that approximately 23% of all police officers in the United States are alcoholics. To put that into perspective, there are an estimated 800,000 sworn officers in the United States which would mean approximately 184,000 officers are considered alcoholics. Some officer’s may have already been or will eventually become alcoholics, prior to being hired, due to genetic predisposition or the environment they were raised in. While this may be true, it is easy to see how the job and the lack of mental health resources available would lead to such troubling statistics.

The day I was hired and sworn in as a police officer, a family friend, who was an active duty police officer at the time, told me that I now had “a front row seat to the greatest show on earth.” Without knowing what the job entailed and the mental health issues that face police officers, I find it somewhat ironic that my family friend and I were drinking at the time. I saw the occasion as a celebration while he may have seen it as a way to self medicate to ease the pain of the demons he carried with him as a result of being a cop. The idea that I could sign up for a job where every day, every hour, and every minute was different sounded too good to be true. And at first, this was exactly what it was like for me every time I pulled that bullet proof vest over my head, buttoned up my uniform shirt, and shined my boots. Today, every time I put on that vest, I am quickly overcome with stress and anxiety of the unknown. The adventures of the job and the adrenaline filled incidents that I yearned for quickly became mundane and I felt as if I was becoming complacent which is a killer in this job. “The very nature of police work includes regular and ongoing exposure to confrontation, violence, and potential harm. Exposure to potentially traumatic experiences on a regular basis sets the stage for a series of mental health complications, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)” (Maguen et al., 2009, p. 754).

Perhaps it was because of the COVID lockdowns without much else to do, or perhaps it was me subconsciously self medicating from the stress of the job, but I soon found myself drinking almost every night. My fiancé recognized this and quickly made me realize that it was becoming a problem. I am extremely fortunate and grateful that my fiancé had the courage to speak up and confront me about my drinking habits. For many this resource is not available and they are left searching for help while fighting to stay anonymous. The search may continue long enough where officers feel they don't have any options and end up take their own lives. “Law enforcement suicide is real and is the number one killer of police officers,” occurring “1.5 times more frequently than suicide in the general population” (Rousseau, 2021, p. 7).

The stigma around mental health and its subsequent treatment is extremely prevalent in law enforcement but the more alarming issue is the lack of resources available to officers. This may be because of the stigma but leaders within the profession have a moral and ethical obligation to do better. I have heard from some classmates that their departments offer mandatory mental health services without questions asked and their colleagues are far better for it. This is an example of forward thinking leadership while combating the stigma that surrounds mental health. The country needs more leaders like this to step up and take care of their own. This will not only lead to healthier officers but it will also lead to better relationships with the public they serve.

Bibliography:

“How Common Is Alcoholism with Police Officers? - The Recovery Village.” The Recovery Village Drug and Alcohol Rehab, The Recovery Village Drug and Alcohol Rehab, 22 Dec. 2020, www.therecoveryvillage.com/alcohol-abuse/related-topics/facts-alcoholism-police-officers/.

Maguen, S., Metzler, T. J., McCaslin, S. E., Inslicht, S. S., Henn-Haase, C., Neylan, T. C., & Marmar, C. R. (2009). Routine Work Environment Stress and PTSD Symptoms in Police Officers. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 197(10), 754–760. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0b013e3181b975f8

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 6 Study Guide [Notes]. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Self-Care and Trauma

People who experience trauma deserve to be free from the weight and pain that it bears upon them. Throughout this class, we have discussed multiple treatment methods that can work individually or that can be used together to find the best treatment plan for the individual. Not all treatments are as widely accepted as others and one that seems to walk on that fine line is self-care. Self-care however is an important part of healing from the trauma, but it should be started when the individual is ready for that experience. Trauma affects our entire body, mind, and our whole being. When all of these aspects are affected we have a harder time being present, connecting, and relating to others. By focusing on ourselves through self-care, our mind and body can work together again to create a healthy and happy lifestyle that may have not existed before.

Highland Springs Clinic mentions that on one’s journey to healing and recovering from a traumatic event, it is important to remember the practice of self-care. They also wrote that “self-care is not commonly the first method survivors think of when they are overcoming a traumatic experience, however, it is a critical part of healing”(Hood,2020). Before starting any kind of trauma therapy, it is important to understand what trauma is and how it may present itself in you. Knowing when to start self-care is dependent on the individual and they have to allow themselves to be ready. Self-care is not the same for everyone, but listening to your body and mind and what it needs is a first step for starting this journey. Our body usually recognizes what we need and will signal to us when the time for recovery is here. Highland Springs Clinic mentions some areas of self-care that are good to start with are get more rest, find someone to talk to, journal about it, use exercise as a tool, and find engaging hobbies (Hood, 2020). While this is only a shortlist of self-care options they are good places to start for people who are ready to treat their trauma by loving themselves.

Whitney Goodman LMFT, a licensed psychotherapist brings up a good point that self-care is supposed to make us better in the long-term and that it is not a quick fix. In society now, the term “self-care is officially a commodity, and people are buying it off the shelves to prove that they care about themselves”(Goodman, 2019). It is important that people who chose self-care to help them with their trauma understand that learning to love yourself and take time for yourself is not an easy process. Goodman stated “real self-care happens in the decisions you make every day and it requires practice, commitment and putting yourself first and getting in touch with what you really need, not just what you really want”(Goodman, 2019). Her short list of self-care is: get in touch with your feelings and actual needs, practice kindness, and ask yourself “what do I need at this moment”. One big point that Goodman and Highland Springs Clinics mentioned is staying away from drinking or using substances since it is not self-care. There are so many different kinds of self-care out there, that experimenting with them will help us find which ones work for us. It is important that people who have experienced trauma believe that they deserve self-care before starting to practice it.

Everyone that goes through a traumatic experience reacts differently emotionally, psychologically, and physically. Being able to accept and be ready for the step of self-care is important to accept the responsibility for yourself, your body, and your mind. Finding a positive self-care routine when ready to embark on the journey will help the overall healing process. It is important to remember that there is no right or wrong way to self-care, it is all about what helps that individual after trauma to become whole again. Dr. Bessel Van Der Kolk writes “the full story can be told only after those structures are repaired and after the groundwork has been laid: after no body becomes some body”(Van Der Kolk, 2015, p.249). Trauma is stressful, but acting on self-care can alleviate that stress. As well as realizing that the trauma needs to be dealt with in a positive way and wanting to deal with it will help accomplish the first step with the journey of self-care.

References

Goodman, W. (2019, July 12). When Self-Care Becomes a Weapon. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/healing-together/201907/when-self-care-becomes-weapon.

Ph.D., D. Julia. Hood. (2020, January 27). The Importance of Self-Care After Trauma. Highland Springs. https://highlandspringsclinic.org/blog/the-importance-of-self-care-after-trauma/.

Ocrcc. (2020, October 12). self-care Archives. OCRCC. https://ocrcc.org/tag/self-care/.

Van Der Kolk, B. (2015). The Body keeps the score brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Complicity is dependent on what from the ordinary people?

Even with the magnitude of the Holocaust serving as a reminder of humanity’s complicity to sadistic values, genocide continues to be an enduring issue that challenges our core beliefs of right and wrong. The Bosnian genocide, the East Timor genocide, and the Darfur genocide—these are some of the mass killings committed after the Holocaust, and despite those lessons learned from the atrocities in Auschwitz, genocide is a nationwide concern that has motivated many scholars and researchers to understand the social context of such behaviors in hopes of fore-fronting changes.

According to Dr. Rousseau, genocide is dependent on the complicity of ordinary people, but to what extent (2021)? While complicity emphasizes the involvement with others in an activity considered as wrong, how subjective is this threshold when measuring someone’s contribution? Though the parameters can vary from active engagement to the bystander effect, both ends of the spectrum ascertains that free will has a strong influence on complicity and its connection to moral judgment in a genocide context (Adelman, 2003).

In the Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE), scholar Philip Zimbardo exploited a controlled observational experiment to examine the focus of social influences and perception through the psychological effects of power and conformity between the prisoners and the prison guards (1971). Conveyed as the main highlight, upon provided a new fictitious identity, both prisoners and guards disengaged their moral values and immediately embraced their new characters, accepting the psychological abuse and power without hesitation (Alvarez, 2015). Reiterated by Elie Wiesel’s autobiographical account, Night, concepts of “right” and “wrong” disappear the moment the first transport arrived in Auschwitz (2006). Does the setting have any influences over the nature of cognitive awareness on moral values? According to Zimbardo’s findings, the study highlighted the observed behaviors from the undergraduate students as a situational occurrence—reinforcing that it is not always of a dispositional attribute or innate behavior (McLeod, 2012).

Additionally, in the Milgram Experiment, scholar Stanley Milgram extended Zimbardo’s situational finding by studying obedience to authority. In its entirety, if placed in the right situation, people will comply to authoritative directives even when it challenges their moral values (Syzdykova, 2014). While the study highlights a selective characteristic that qualifies responsibility as the determining factor for such involvement, the study really sheds light on the conflict between obedience to authority and personal conscience. In its face-value, obedience to authority takes on Zimbardo’s analysis of situational attribution, meanwhile, the path to decisions falls on the phenomenon of free will—the ability of oneself to cognitively decide. As a result, which theory best answers one’s complicity to behaviors like genocide—situational or dispositional?

While the Reserve Battalion 101, a paramilitary formation during the Holocaust responsible for the expulsion of Poles to the mass shootings of Jews, operated on a mechanistic view of moral judgment that describes both situational and dispositional patterns, how does our understanding of the SPE and the Milgram Experiment describe which attribute best explains the threshold of complicity to genocide? According to Browning, Zimbardo’s study was more relevant to the Reserve Battalion 101 given many of the men in the battalion were ordinary people, with no criminal records or history of murderous and heinous beliefs (1992). Similarly to the undergraduate students, the results shed light on their ability to selectively engage and disengage moral standards (Alvarez, 2015). The selectively engagement and disengagement is seen through their hesitation. Characterized by Browning, “while the men of Reserve Police Battalion 101 were willing to shoot Jews too weak or sick to move, they still shied for the most part from shooting infants, despite their orders” (1992). This behavior of feeling “shied” is the inner moral workings and conflicts of obedience to authority, willingness to participate, and deferment in responsibilities.

Although some may argue the environment offers a situational attribute that persuades one to behave in a certain manner, these decisions to engage or to disengage are part of a constant rationalization that occurs in a person’s free will. Doing the right thing versus becoming self-preserved in order to avoid the apathy of fear and embarrassment—these are some of the thought processes that are passively being sourced through a cost-benefit analysis to determine which action is more suitable for the person, in the specific environment. As a result, despite situational factors, dispositional best supports that genocide is dependent on the complicity of the individual, arguing that everyone passively engages in rationalizing for their own benefit.

References

Adelman, H. (2003). Review: Bystanders to genocide in Rwanda. The International History Review. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40109323

Alvarez, K. P. (2015). The Stanford prison experiment. IFC Films.

Browning, C. R. (1992). Ordinary men: Reserve police battalion 101 and the final solution in Poland. HarperCollins.

McLeod, S. (2012). Attribution theory. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/attribution-theory.html

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 5: Trauma, Genocide, and the Holocaust. Boston University Metropolitan College: Blackboard.

Syzdykova, K. (2014). The Milgram experiment. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=760lwYmpXbc

Zimbardo, P. (1971). The Stanford prison experiment: A simulation study of the psychology of imprisonment conducted August 1971 at Stanford university. Stanford University. https://web.stanford.edu/dept/spec_coll/uarch/exhibits/Narration.pdf

Acupuncture as Trauma Therapy

Over the relatively short period of time that trauma treatment has been studied, there has been a myriad of different methods proven to help trauma victims in one way or another. Despite this, there is yet to be a cure-all that works completely for every individual and every trauma. To fully accept the reality of a trauma and be free from the weight it bears, multiple treatment methods working in tandem with one another is the best approach for healing.

One treatment method that is less often discussed but proven effective is acupuncture. Acupuncture is an ancient Chinese practice that utilizes small needles placed along pressure points on the body to help with energy flow and pain relief. Chinese documents dating as far back as 100 BCE describe the system of diagnosis and treatment that is now recognized as acupuncture (White & Ernst, 2004). The original idea of flowing meridians in the body has given way to modern neurology’s explanation that the needles stimulate nerve endings and brain function (White & Ernst, 2004). While the practice is centuries old and has been utilized in cultures across the globe, there is surprisingly little research on its effects.

Although there is little research on the subject, other forms of therapies have developed from its principles. Emotional Freedom Techniques is a more common method that, while self-administered, relies on the same bodily energy flows as acupuncture and has also been proven to cure the physical and psychological effects of trauma. In a survey following the September 11th attacks, the 225 individuals questioned said that acupuncture was the most effective method in helping them overcome the immediate trauma of being in the Towers (Van der Kolk, 2014). Acupuncture has also been found to be a “promising treatment option for anxiety, sleep disturbances, depression and chronic pain” as related to the trauma spectrum responses (Lee et al., 2012). While more research is needed to identify the mechanism of action between the needles and the actual relief, the success stories speak for themselves and make the practice a worthy contender for comorbid treatment.

The way acupuncture can aid in trauma recovery is by alleviating the symptoms either directly or residually caused by the event. For example, after a car accident, an individual might suffer pain in their neck and experience anxiety whenever they are in a car again. Acupuncture can help to relieve the neck pain that both hinders quality of life and acts as a constant reminder of the accident. Chronic pain is also a common side effect of adverse childhood experiences. When an adult comes in for therapy with a long history of repeat traumas, alleviating physical pain is a great starting point to begin recovery. This allows for a greater sense of control in one’s own body and opens doors for further therapeutic practices like yoga and exercise that would not have been possible with chronic pain. Acupuncture may not be the cure-all that therapists and researchers are looking for to help their patients overcome past traumas but its longstanding history and overwhelming success rate for non-trauma related pain demands more research be conducted on the practice’s effects on trauma.

References:

Lee, C., Crawford, C., Wallerstedt, D., York, A., Duncan, A., Smith, J., Sprengel, M., Welton, R., & Jonas, W. (2012). The Effectiveness of Acupuncture Research Across Components of the Trauma Spectrum Response (TSR): A Systematic Review of Reviews. Systematic Reviews, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-46

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. [VitalSource Bookshelf]. Retrieved from https://bookshelf.vitalsource.com/#/books/9781101608302/

White, A., & Ernst, E. (2004). A Brief History of Acupuncture. Rheumatology, 662–663. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keg005.