Kaitlyn McDonald

The Ballets Russes- Fokine, Balanchine, and Stravinsky

Introduction–

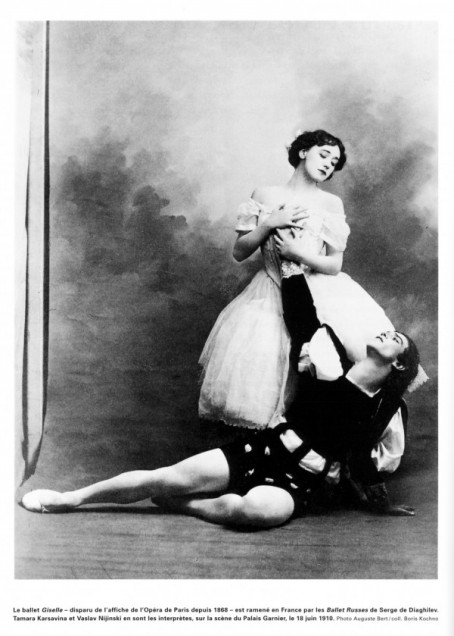

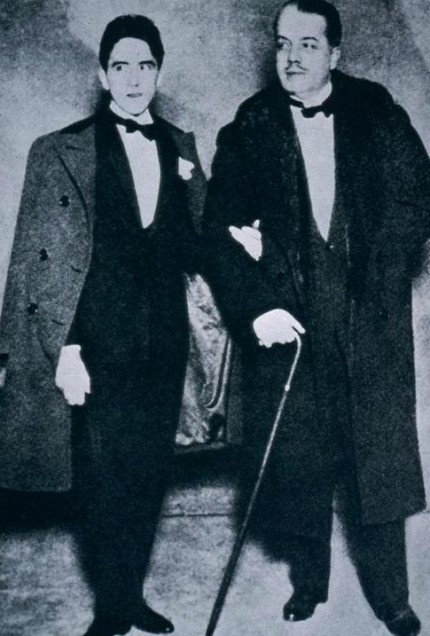

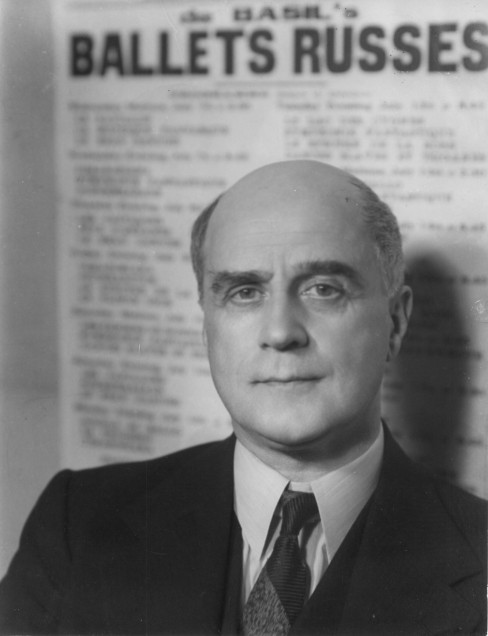

The Ballets Russes (1909- 1929), formed by Serge Diaghiliev, remains one of the most influential and innovative epochs of dance history. The Ballets Russes brought together dancers like Vaslav Nijiinsky, Anna Pavolova, Tamara Karsavina, and Serge Lifar with composers Igor Stravinsky, Maurice Ravel, Claude Debussy, and Sergei Prokofiev as well as artists and designers such as Léon Bakst, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Alexandre Benois, and Coco Chanel. Thus, the impact and scope of the Ballets Russes is vast. However, the company’s most influential works: L’Oiseau de Feu, Petrouchka, Le Spectre de la Rose, Rite of Spring, and Apollon musagete were all composed by Stravinsky. The first work was choreographed by Fokine and the last by Balanchine.

These works were the result of Russian émigré collaboration; they interact with the Russian tradition and the cultural movements of their home. Yet. they are not truly part of that cultural narrative anymore. They inhabit a liminal space, not part of the East, but not fully part of the West either. The collaborations of Fokine and Balanchine with Stravinsky acknowledge their Russian heritage while challenging the aesthetic movements of their home countries. Just after Gorsky restages Petipa’s works at the turn of the century, Fokine desires to create a Russian ballet for himself. It is not an extension of imperially sponsored traditional ballet, yet it is a product of it. Stravinsky’s music for L’Oiseau de Feu feels like an echo of Tchaikovsky, but there is an unsettled, jarring quality to it that never quite settles itself into the realm of the safely traditional. The libretto for the ballet is based on Russian folk tales, but it is heavily orientalized for Western audiences. Stranger than that, it is then accepted back by Russia when it is restaged by Fyodor Lupokhov. It is even judged to be an acceptable, ideologically sound ballet when the Soviets publish a document rating the repertoire. Russian criticism on Stravinsky varies wildly, Asafiev finding him delightful while he is denounced by Alshvang as too bourgeois. Apollon musagete is choreographed by former Mariinsky dancer Balanchine. As neoclassical movements in art and architecture sweep through Russia, stifling the avant-garde in favor of more classical literature and art, Balanchine and Stravinsky create a consciously neoclassical work. It strips ballet of the decadent stagings so loved by Diaghilev and presents a work that is spatially and temporally aware. The collaboration between Stravinsky and Balanchine was the first of many and it changed the way the world viewed ballet. Insular as the USSR became, even they were not ignorant of Balanchine’s innovations. The revolutionary conditions in Russia which urged so many of its artists and intellectuals to flee also urged them to continue to engage with the culture of their home.

General Information on Ballet:

Homans, Jennifer. Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet. New York: Random House, Inc., 2010.

This provides a general background to ballet, tracing it to 16th Century France, bringing the Italian Renaissance to France through the marriage of Henri II and Catherine de Medici. While the first section discusses the importance of ballet’s development in France and Italy, the second section introduces the lasting association of classical ballet with Russia. Chapters 7, 8, and 9 are of particular interest, as they deal with Marius Petipa’s work in imperial Russia, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris, and Soviet ballet respectively. Homans was a dancer herself, giving her work an artistic, aesthetic sensitivity many other ballet histories fall short of.

The Cambridge Companion to Ballet. Ed. Marion Kant. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Another excellent resource for genera ballet background, this work has the advantage of multiple authors and scholars writing on their topics of interest. Chapter 13, “Russian ballet in the age of Petipa” by Lynn Garafola not only illustrates the lasting legacy of Petipa’s works, but also elucidates the deep connections between the ballet and the tsarist regime. Tim Scholl’s chapter, “The ballet avant-garde II: the ‘new’ Russian and Soviet dancers in the twentieth century”, traces Russian ballet from c. 1900 to c. 1930. His chapter also provides a brief introduction to choreographers Michel Fokine, Alexander Gorsky, and Fyodor Lupukhov as well as the impact of the Ballets Russes. Finally, Juliet Bellow’s “Balanchine and the deconstruction of classicism” examines Balanchine’s neoclassical, deconstructionist approach to Apollon musagete (1928) and its tension with the traditional ballet canon, as exemplified in André Levinson’s scathing review.

Reynolds, Nancy & Malcom McCormick. No Fixed Points: Dance in the Twentieth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

A gargantuan book full of photos, No Fixed Points examines modern dance, popular dance, Broadway, and film in addition to its study of ballet companies. Chapters 2 and 7 are of particular interest, as they examine the former examines the choreographers of the Ballets Russes and the latter the evolution of Russian ballet through revolution, Stalinism, and the Cold War. For a work of such scope, it is surprisingly detailed and aware of ballet’s cultural crossover with other artistic forms.

Scoll, Tim. From Petipa to Balanchine: Classical Revival and the Modernization of Ballet. London: Routledge, 1994.

Scholl’s work introduces the imperialist golden age of ballet under the guidance of Petipa, its revival under Gorsky, and experimentation under Diaghilev in the Ballets Russes. While the entire work is useful at establishing historical context for the work done by Fokine and Balanchine, the third and fifth chapters are the most useful. The third is dedicated to the Ballets Russes while the fifth examines the publication Apollon and Balanchine’s Apollon musagete.

Russian Cultural History: General Sources

Bowlt, John E. Moscow & St. Petersburg:1900-1920, Art, Life, & Culture. New York: Vendome Press, 2008.

This resource shows just how interconnected the arts were, tying painting and literature to ballet and composing. It is an excellent visual resource, reproducing many sketches, paintings, and photographs from the period. It is worth noting that Bowlt is one of the foremost scholars on art and culture in this time period and one would be hard-pressed to find a book pertaining to the period which does not cite at least one of Bowlt’s works.

Clark, Katerina. Petersburg: Crucible of Cultural Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Clark’s work deftly navigates the cultural movements and changes taking place from the twilight of the imperial regime through to the Stalinist culture established by the 1930s. Though the entire work is useful, the chapters “The Establishment of Soviet Culture” and “The Ultimate Cultural Revolution” are the most pertinent for establishing the counter-point to the work being done by the Ballets Russes abroad. These chapters discuss the prevalence of Socialist Realism as well as a neoclassical revival, a trend of looking back to great Russian literature, art, and music.

Elliott, David. New Worlds: Russian Art and Society 1900-1937.

Another excellent visual resource, especially for advertisements and propaganda posters. Elliot’s work focuses on revolutionary and post-revolutionary culture, spending less time with Mir iskusstva and other pre-revolutionary movements. This serves as an excellent resource to compare Ballets Russes later work to the artistic movements occurring within revolutionary and Soviet Russia.

Figes, Orlando. Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002.

Natasha’s Dance is, perhaps, one of the most comprehensive and readable cultural histories of Russia in print. The entire book comes highly recommended as Figes effortlessly weaves together works of artistic and cultural importance with their political and social contexts. From Diaghilev to Tolstoy to Kadinsky, Figes links Russian artists, writers, and intellectuals to historically and culturally important events and movements. “The Peasant Marriage” and “Descendants of Genghiz Khan” are excellent example chapters. However, picking only one or two chapters would be to abominably underuse this text.

Gaborik, Patricia and Andrea Harris. “From Italy and Russia to France and the U.S.: ‘Fascist’ Futuristm and Balanchine’s ‘American’ Ballet”. Avant-Garde Performance and Material Exchange: Vectors of the Radical. Ed. Elaine Aston and Bryan Reynolds. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

This essay discusses Balanchine’s Russian roots, Italian influences, and American audience with regard to the development of his style. Considering Stravinsky/ Balanchine collaborations requires thinking not only of their reactions to Russian movements and deeply ingrained Russian backgrounds, but the Western influence on their works as they worked beyond the reaches of the USSR. This considers the aesthetics of Balanchine’s choreography in nationalistic terms, setting it apart from typical dance scholarship.

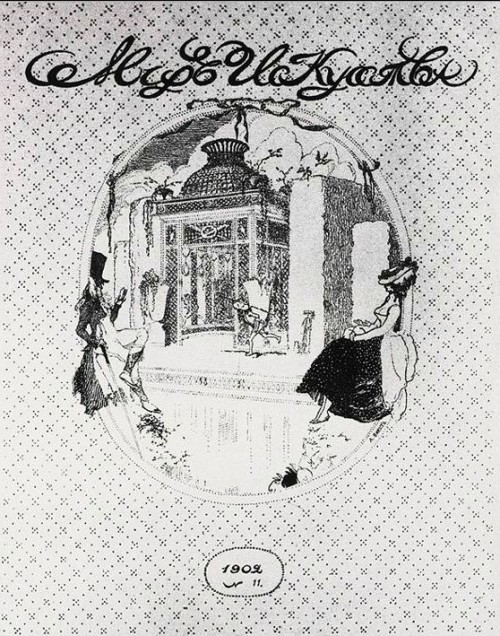

Ballets Russes and Mir Iskusstva

Before the creation of the Ballets Russes in 1909, there was the Mir iskusstva group, also lead by Diaghilev. Many members from this original group followed Diaghilev to Paris for the formation of the Ballets Russes. Both groups brought together musicians, artists, designers, writers, dancers, and aestheticists to create and preserve art. Consideration of Mir iskusstva also provides a cultural and historical context to view the Ballets Russes against.

Kennedy, Janet. The “Mir Iskusstva” Group and Russian Art 1898-1912. Diss. Columbia University, 1976. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1977. Print.

This dissertation attempts to provide a full account of the Mir iskusstva group in a single volume. While the bulk is dedicated to Mir iskusstva the journal, Kennedy discusses their reform movements, aesthetic aims, and their criticism. Later chapters include profiles on individual members, including Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst, who both contributed to librettos, set designs, and costumes for the Ballets Russes. The final chapter is of particular interest, as it discusses the connection Mir iskusstva between the Ballets Russes.

Laboratory of Dreams: The Russian Avant-Garde and Cultural Experiment. Ed. John E. Bowlt and Olga Matich. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

This book contains a collection of essays from various contributors split into sections that deal with cultural innovation, semiotics, and socialist realism. The essays by Bowlt, Clark, and Groys are of particular interest as they deal with avant-garde conceptions of the body, retrospectivism, and socialist realism respectively. Clark’s essay is especially interesting, as it engages with Groys and suggests that the avant-garde and retrospectivists both affected and were effected by Stalinism, refuting Groys inclination to see the 1920s and early 1930s as a sort of cultural agon between the two groups.

Raeff, Marc. Russia Abroad: A Cultural History of the Russian Emigration, 1919- 1939. Oxford: Oxford University Press,1990.

This book addresses the problems of considering Russian émigrés within the greater Russian cultural history. Raeff suggests that Russia Abroad is a country unto itself, one without “physical or legal boundaries”. The chapter “To Keep and to Cherish: What Is Russian Culture” is particularly interesting, as it mentions the importance of theatre, music, and dance with a section on the lasting importance of Stravinsky and Balanchine.

Schouvaloff, Alexander. The Art of the Ballets Russes. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

This book is an excellent visual resource on the Ballets Russes. Most of the major productions of the Ballets Russes are included, with sketches and photographs of original set designs and costumes. Additionally, each section gives a synopsis of the ballet and the original cast, composer, conductor, etc.

Spencer, Charles. The World of Serge Diaghilev. London: Paul Elek Ltd., 1974.

While this book does provide a brief run through of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, it is not as thorough as Bowlt’s works. It does, however, include a wealth of sketches, paintings, photographs, and playbills.

Van Norman Baer, Nancy. The Art of Enchantment: Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, 1909-1929. New York: Universe Books, 1988.

This book contains contributions from big names within the field including: Bowlt, Garafola, and Taruskin. Taruskin’s chapter “The Antiliterary Man: Diaghilev and Music” is particularly interesting, as it alleges that Diaghilev was not a master of taste, but an undisciplined, unaccomplished musician who merely perpetuated aristocratic artistic sensibilities earlier formed with his Mir iskusstva group. Aside from its essays, The Art of Enchantment contains many sketches and photographs. It’s only drawback is that it only includes footnotes and lacks an organized bibliography at the end.

Bowlt, John E. The Silver Age: Russian Art of the Early Twentieth Century and the ‘World of Art’ Group. Newtonville: Oriental Research Partners, 1979.

This work is similar to Kennedy’s in its attempt to give a general overview of the World of Art (Mir iskusstva) group, many of whose members formed the core of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Bowlts chapter “The World of Art: Its Esthetic” is worth noting, especially his section on Retrospectivism.

Key Players in the Ballets Russes

To state it quite plainly, any examination of the collaborations between Stravinsky and Fokine or Balanchine requires the accounts of their lives. Beyond that, it requires a rounded view of works like L’Oiseau de Feu or Apollon musagete. The autobiographies of Alexandre Benois and Tamara Karsavina provide a fuller account of the tumultuous Ballets Russes and the complex relationships between dancers, choreographers, composers, and ballet master Diaghilev. Diaghilev was known for his mercurial temperament and his shameless promotion of favorites like Vaslav Nijinsky and Serge Lifar. Stravinsky felt pressured to create L’Oiseau de Feu in a manner disingenuous to his own taste and style of composition. Later, Diaghilev felt scorned by Stravinsky’s composition of Apollon musagette for performance at the American Library of Congress. The tensions at the Ballets Russes ultimately lead to a narrative which is multi-faceted and open to interpretation.

Primary Sources:

Benois, Alexandre. Reminsces of the Russian Ballet. London: Wyman& Sons, Ltd., 1941.

Benois was involved in both Mir iskusstva and the Ballets Russes. The third section of his book is of the most interest, as it is the one that deals with the Ballets Russes, collaborations with Fokine and the productions of L’Oiseau de Feu, Petrouchka, and the seasons through 1914.

Reading Dance. Ed. Robert Gottlieb. New York: Random House, Inc., 2008.

An invaluable resource for anyone wishing to write about dance in the twentieth century. Though this does contain secondary commentaries, the bulk of the book is first-hand accounts, letters, diaries, and notes. Anyone researching the Ballets Russes should look into the sections on Diaghilev and Balanchine, especially Balanchine’s essay “Marginal Notes on the Dance”.

Fokine, Michel. Fokine: Memoirs of a Ballet Master. Trans. Vitale Fokine. Ed. Anatole Chujoy. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1961.

Fokine’s memoir gives his account of the creation of his major works. Most importantly, Fokine comments on the original stagings and the changes made to his work in later adaptations. As ballets are constantly rechoreographed and reinterpreted, his insight on the original costumes, choreography, and casting helps to explain differences between the original work and the way it is viewed and performed today.

Karsavina, Tamara. Theatre Street: the Reminisces of Tamara Karsavina. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1930.

Karsavina was a ballerina with the Ballet Russes and had the main roles in the ballets L’Oiseau de Feu, Petrouchka, and Le Spectre de la Rose. Her work gives an alternate insight to Fokine as a choreographer as well as the reign of Diaghilev.

Stravinsky, Igor and Robert Craft. Memories and Commentaries. New York: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2002.

This work takes the format of an interview, one that is incredibly revealing. Stravinsky talks of his frustrations with Firebird (L’Oiseau de Feu), his disappointment with Nijinsky’s choreography for Rite of Spring, and the evolution of Apollon musagete. The early section of the book include insights on Stravinsky’s early life in Russia and his artistic influences.

Stravinsky, Igor. An Autobiography. 1936. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1962.

This autobiography, much like the work above, gives Stravinsky’s memories on the creation of his music, his relationship with Diaghilev, and his collaborations with Balanchine. It is a short, engaging autobiography, but lacks the depth of analysis and reflection seen in Memories and Commentaries. Nevertheless, this volume complements Memories and Commentaries, giving a cohesive story rather than the thematic organization of Craft’s work.

Lifar, Serge. Serge Diaghilev: His Life, His Work, His Legend- An Intimate Biography. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1940.

This “intimate biography” comes from ballet dancer and Diaghilev favorite Serge Lifar. Lifar discusses his time with the ballet master as well as his roles in various works including Balanchine’s Apollon musagete. Reader beware, though this gives insight into Diaghilev’s favoritism and a bit of Lifar’s career, their relationship certainly sways Lifar’s view of Diaghilev. This work ought to be balanced by looking at other, less adoring accounts of Diaghilev.

Secondary Sources.

Buckle, Richard. George Balanchine: Ballet Master. New York: Random House, 1988.

Buckle is an often cited author whose other works include studies of Diaghilev and Nijinsky. This work chronicles Balanchine’s life from birth to death, with the first two chapters covering his early life and his time at the Ballets Russes.

Scheijen, Sjeng. Diaghilev: A Life. Trans. Jane Hedley-Prôle and S. J. Leinbach. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

This exhaustive work of Diaghilev draws on existing historiography to form an impressive bibliography. Scheijen is not a dance historian, as evident by its lack of interest in summarizing and interpreting choreography. It is less reverent than biography’s like Lifar’s and looks at Diaghilev as a man rather than a quasi-mythic innovator. This work helps to sketch out a more neutral image of Diaghilev than those presented by his contemporaries.

Works on Stravinsky’s Ballets

The major works of the Ballets Russes, L’Oiseau de Feu, Petrouchka, Le Spectre de la Rose, Rite of Spring, Apollon musagete, etc were all composed by Stravinsky. To examine the impact of any of these works requires inquiry into Stravinsky and his place within the musical world. These works also examine his relationship with his choreographers, especially Balanchine as their working relationship spanned decades.

Carr, Maureen A. Multiple Masks. Neoclassicism in Stravinsky’s Works on Greek Subjects. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Carr examines some of Stravinsky’s neoclassicism, a hallmark of ballets like Apollon Musagete and Orpheus. For the study of the Ballets Russes, the first and third chapters are the most useful as they are “Literary Musical and Artistic Sources for Stravinsky’s Neoclassicism” and “Apollo: Stravinsky’s Compositional Process”. This text focuses on Stravinsky’s influences and inspirations as well as his creative process before moving to examine the music itself. It contains some of the original, hand-written sheet music, an added resource for anyone that can read music.

Joseph, Charles M. Stravinsky’s Ballets. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011

Joseph’s book tackles issues of composition, libretto, and choreography for each major Stravinsky work. The evolution of the works from their conception through the composing process is traced with attention to Stravinsky’s collaborations with Diaghilev and the choreographers of the Ballets Russes. The first five chapters cover Stravinsky’s early life through Apollon musagete in 1928, just before the dissolution of the Ballets Russes at Diaghilev’s death a year later.

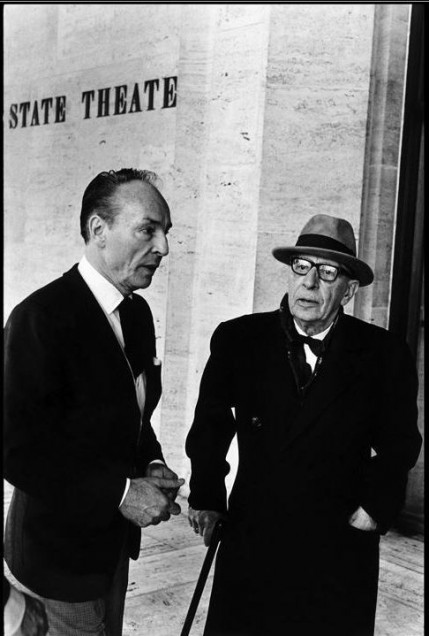

Joseph, Charles M. Stravinsky & Balanchine: A Journey of Invention. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

This book focuses specifically on the working relationship between Stravinsky and Balanchine. For the purposes of studying their time at the Ballets Russes, chapters four and five are most pertinent as they detail the initial creation of Apollon musagete for an event at the American Library of Congress to its revival in Paris with the choreography of Balanchine.

Stravinsky in the Theatre. Ed. Minna Lederman. New York: Pellegrini & Cudahy, 1949.

This work includes primary sources such as Stravinsky’s own comments on his work, “The Dance Element in the Music” by George Balanchine, and excerpts from longer works by André Levinson, Nicolas Nabokov, and Jean Cocteau. The appendix also includes lists of stagings for Stravinsky’s ballet’s (through the books publication in 1949).

Criticism and Reception

Primary Sources

Alshvang, Arnold. Izbrannye sochineniia. Moscow: Izdatelstva Muzyka, 1964.

This source is entirely in Russian and has not been widely translated. It is a collection of essays on music, including Stravinsky’s. Alshvang’s criticism is heavily Soviet and accuses Stravinsky of being both bourgeois and Western.

André Levinson on Dance: Writings from Paris in the Twenties. Ed. Joan Acocella and Lynn Garafola. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1991.

Though published in Paris, Levinson was a Russian-born critic. His essays show that not all Russian émigrés in Paris were worshippers of Diaghilev. Levinson’s essays “A Crisis in the Ballets Russes” and “Stravinsky and the Dance” are the most pertinent as criticism and review of the Ballets Russes.

Secondary Sources

Järvinen, Hannaa. “‘The Russian Barnum’: Russian Opinions on Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, 1909-1914”. Dance Research: the Journal of the Society for Dance Research. 26.1 (2008): 18-41.

This article discusses some of the Russian criticism of the early seasons of the Ballets Russes. Works like L’Oiseau de Feu and Rite of Spring, which exoticized and orientalized Russia for Western audiences, were equally criticized and embraced by the intellectuals of Russia. This provides insight on reviews and criticisms published in Russian journals which may be otherwise inaccessible.

Rabinowitz, Stanley J. “From the Other Shore: Russian Comment on Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes”. Dance Research: the Journal of the Society for Dance Research. 27.1 (2009): 1-27.

This article offers the differing opinions of Russian musical critics Volynskii and Lunacharskii. Volynskii followed the Russian diaspora to Paris while Lunacharskii became the Commissar for Enlightenment in Russia. As Rabinowitz notes, these criticisms have been translated into English for the first time. To consider the relationship between Russians abroad and Russians in Russia, this article is an excellent resource.

Schwarz, Boris. “Stravinsky in Soviet Russian Criticism”. The Musical Quarterly. 48.3 (1962): 340-361.

Shwarz’s compilation of important Soviet criticism is a wonderful resource both in itself and for its bibliographic information. Many of the journals and publications which contain such reviews are difficult to access or obtain, making Schwarz’s article all the more useful.

Souritz, Elizabeth. Soviet Choreographers in the 1920s. Trans. Lynn Visson. Ed. Sally Vanes. Durham: Duke University Press, 1990.

This work provides a set of Soviet Russian choreographers against which the Ballets Russes can be compared. The relevance of Ballets Russes works, such as Fokine’s L’Oiseau de Feu and Petrouchka are evident through Lopukhov’s restagings. The book also touches on Balanchine’s early life as a dancer and choreographer at the Mariinsky Ballet and his ensemble the Young Ballet.

Swift, Mary Grace. The Art of the Dance in the USSR. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968.

This book begins with pre-revolutionary, tsarist ballet and stretches into the Cold War. The Ballets Russes and its various members are frequently mentioned as dancers fled from Russia and, less frequently, returned. An appendix at the end gives the Repertoire Index of 1929, which rated ballets on a scale from A “the best works ideologically” to E “forbidden”. Stravinsky’s ballets with the Ballets Russes have all been given an “A” rating.

Multimedia Sources

This production of Apollo dates to 1960. Though the choreography is still Balanchine’s, he continually revised his work throughout his life, so the Apollo (Apollon musagete) seen onstage today is not the same ballet that debuted in 1928. Though, the Balanchine Trust now serves to protect his choreography from further revision. This version is one of the few, complete versions that can be found. The Balanchine Trust is very selective about what companies can perform the Balanchine repertoire and reproductions through film are even more strictly monitored. The costumes resemble those done by Coco Chanel in 1929 and the minimalist set is a departure from the original 1928 production. Balanchine, a trained musician himself, carefully fits the geometric shapes of his dancers to the music. Balanchine’s connection to music extends beyond the mere texture or contours of a piece, but delves into the subtleties and complexities in a way only musicians can. Thus, his ballet blanc is in harmony with the music, represents it, embodies it.

Similar to the above, the Firebird (L’Oiseau de Feu) of Today is not the same ballet that premiered more than a century ago when Fokine choreographed it. His autobiography speaks to some of the changes that have been made. Though it is not the same, the music and libretto remain the same. As imperfect a representation as it is, it does still retain some of its Russian, exoticized roots. There is something in the angle of the arms that echoes Don Quixote, yet there is something unsettling in it. The music has a touch too much of the Orient and the movement is too jarring and angular to be classical.

To truly appreciate the modernism and experimentalism of the works produced by the Ballets Russes, it is useful to compare it to a classical, romantic ballet such as Giselle. To forge the connection further, the Ballets Russes staged a production of Giselle in their 1910 season featuring Anna Pavolva as their lead. This version is a 2008 production done by the Bolshoi Ballet featuring Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev. The romantic tutus, the traditional, linear formations of the corps de ballet, and the delicacy and classical nature of the movement all speak to the traditional nature of Giselle. The softness of her port-de-bras, the slow développé that languorously reaches its apex before floating towards the ground once more, they embody femininity and 19th Century Romanticism.