Changes in Educational Ideology and Format: 18th to 20th Century Practices

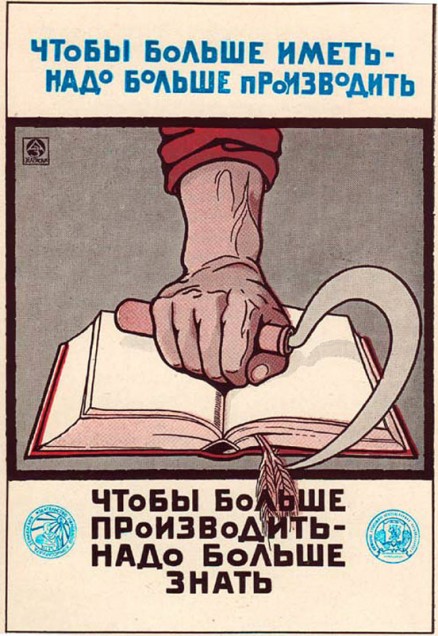

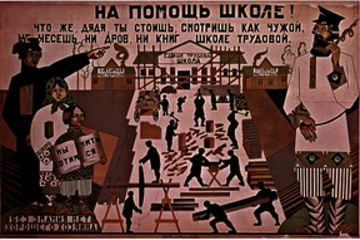

A Soviet poster describing the importance for all to be productive and help build new schools for the proletariat.

This research guide provides a launching point for further study into the topic of eduction in Russia, specifically focusing on the changes that occurred in education due to the transition from Imperial Russia to Bolshevik and Soviet Russia. The time period for this guide begins during the mid 19th century and follows through the mid 20th century. Education in Russia has always been closely associated with society for example it was an exclusive commodity during Imperial Russia when class barriers were firm but as class barrier were broken down during the Russian Revolution education became available to the masses through the Bolshevik ideal of universal education.

Education during Imperial Russia functioned as a means to limit the social mobility of many while it later would serve as a means of social enlightenment during Bolshevik and Soviet Russia. Official state treatment of education shifted with the economic, political, and military issues of each time period. Both Imperial Russia and Soviet Russia utilized education as a means of social control to promote a state agenda or create cohesion. This state approach towards education as a tool begins to demonstrate the complex relationship between state, educational institution, educator, student, and society. To understand the condition of education during these phases of Russian history illuminates the nature of society for the specific period.

Behind many of the major changes in education were state sponsored prerogatives. For example if one where to ask what form did change occur in the educational system? and why did this change occur? The answer would ultimately be tied into a goal or mission of the state. During the reign of Tsar Peter I, compulsory education was initiated as to enlighten and modernize Russian society due to the desire of Peter I to bring Russia out of the dark. Answering the perviously stated questions becomes increasingly difficult as the Bolsheviks and Soviet take power and reshape education. To explain the purpose of universal education one might conclude that it was inline with socialist values but further analysis into this change in educational practice demonstrates state use of education as a means to quell dissenters by creating social cohesion thus solidifying the socialist state.

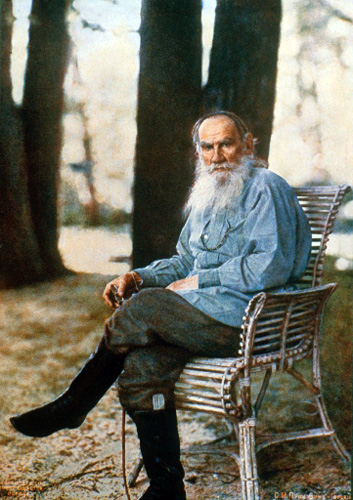

While many of the educational changes that have occurred over time in Russia have been executed a state agenda there have also been many genuine attempts to reformat education for the good of society. During the late 17th centuryTsar Fyodor III valued education and felt compassion for the poor, he took action to create a school specifically for the poor resulting in the creation of The Graeco-Latin-Slavic academy in Moscow. Later on during the mid to late 19th century Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy at the author of War and Peace, opened up his own schools for peasant. The schools he operated utilized organic learning which set them apart from the rigid form of education that was popular in Russia and Europe. The history of Russia education is a constant mixing between hopes and realities as visionaries of educational reform would find their ideas come to life but often to reach an alternative end decided on by external individual or group.

A compilation of sources have been collected on the history of Russian education, the changes of practice, format and ideology of Russia education, and the issues surrounding education at the time. Scholarly journal writings, historiographies, and primary sources make up the majority of the complied sources below. The works are organized under three topics; education during Tsarist Russia, education during early Revolutionary Russia, and Education during early Soviet Russia.

Education During Imperial Russia

Education was predominately exclusive, religious, and limited in length during Imperial Russia. No form of universal public education had yet been established leaving only those with financial means the ability to enroll in educational institutions at the secondary and university level. The gymnasium form of education adopted from Germany provided greater accessibility to education for the elites which contributed to the growth of national culture but also caused a polarization of the educated elite further separating the group from the majority of Russian society. Conservatism was a major theme of these schools both in curriculum and mission. Common curricula at the time focused on classical works, history, political theory, and economics. The common mission of these primary and secondary schools was to mold the student population into a cohesive, mild group that could not become radicalized and cause revolution like that seen in France in 1789. Universities proved a challenge for the Imperial Government and were never tamed due to the influence of intellectuals over the institutions.

- Pipes, Richard. Russia Under The Old Regime. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974.

Richard Pipes provides an overview of education in Tsarist Russia in Russia Under The Old Regime. He provides valuable insight as he highlights the relationships between peasant, clergy, elite and education. Pipes focuses on the reforms initiated by Peter I in regards to education. Under Peter I a system of mandatory education was created for all young men who upon state inspection would be either sent to school or sent off to service. Peter I had the goal of creating an educated Russian population but his reforms such as compulsory education/state service were some of the most despised of all of the reforms.

- Auty, Robert, and Obolensky, Dimitri. An Introduction to Russian History: Companion to Russian studies. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Tsar Fyodor III possessed an appreciation for Western Europe, this materialized through the creation of a Graeco-Latin-Slavic academy in Moscow. This academic institution was created specifically for the children of poorer classes. Peter I set up ‘cypher’ schools staffed by clergy as part of his compulsory education reform. These schools found little success due to the clergies’ inability to teach secular studies and the elite’s disapproval of mixing of social classes in schools. Other fear of rapid educational expansion most notability included the elite’s fear that a chaotic change of social order would occur. The push for mass education that came from Fyodor III and Peter I continued through the early 20th century increasing literacy from roughly 20% in 1897 to 44% in 1914.

- Freeze, Gregory L. Russia: A History. New York: Oxford University Press: 2002.

Gregory Freeze writes extensively on the condition of Russia from the 16th century through the 20th century. He emphasis on transitions in Russia allows the reader to follow the changing education system. In 1667 Russia acquired the left bank of Ukraine bringing an influx of educated men into Russia promoting a new level of scholarship. While Peter I visited Western Europe he recruited experts from Europe, some of the most influential recruits were Joseph Nye, John Deane, John Perry, and Henry Farquharson all who played a role in building Russia’s new navy. With plans drafted by Peter I, The Imperial Academy of Sciences opened in 1725 that would overtime solidify itself as a reputable institution of higher education in Russia.The Spiritual Regulations of 1721 required an educated, literate clergy to do so a seminary system based on the Jesuit seminary system was adopted and common practice by the 1780s. Alexander I took on the challenge of providing higher education regardless of class for Russian by creating universities in Kharkov, Kazan, and St. Petersburg. The growth of education brought about two forces that would challenge imperialism: nationalism and the desire for participation in politics. During the late 1920s of Russia measures were taken to remove privileged groups from higher education replacing them with working class groups.

- Thaden, Edward. Conservative Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Seattle: University of Washington Press,1964.

Conservatism in 19th century Russia can be equated with the phrase Autocracy, Orthodoxy, and Nationality. A major proponent of this conservative push in 19th century Russia was Admiral Alexander Shishkov. Shishkov would influence Russia through his work as Minister of Public Instruction. His attempt to promote Autocracy, Orthodoxy, and Nationality took the form of educating the upper class of Russia to create social cohesion and moral strength for Russia. To do so he worked to replace educational institutions of non-Russian origin (Polish and Catholic) with truly Russian educational institutions. Edward Thaden professor of Russian studies at Pennsylvania State University chronicles the growth of conservatism in 19th century Russia in his work Conservative Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russia. His focus towards education during this period of increased conservatism provides a useful timeline of the evolution of education under Tsarist Russia. His use of officials, scholars, and radicals provides a multitude of angles to view this period of change.

- Ringlee, Andrew. The Instruction of Youth in Late Imperial Russia: Vospitanie in the Cadet School and Classical Gymnasium, 1863-1894. University of North Carolina, 2010.

During the final years of Imperial Russia two starkly contrasting groups of students were produced from the state sponsored schools run by the Ministry of War and by the Ministry of Education. Military cadet schools were run by the Ministry of War while the civilian gymnasium was run by the Ministry of education. Graduates of military cadet schools remained loyal their alma mater years after the collapse of Imperial Russia while graduates of the civilian gymnasium typically renounced former educators and schools. Andrew Ringlee compares the educational methods utilized by the Ministry of War and Ministry of Education during the reigns of Alexander II and Alexander III to understand how participants experienced the two types of institution. An electronic copy if this work can be found here.

- Alston, Patrick L. Education and the State of Tsarist Russia. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1969.

Education under Tsarist Russia progressed through several stages growing in sophistication and autonomy. Peter I brought major changes to the educational system of Russia introducing a new sense of enlightenment to the institutions of education. Towards the late 19th century educators began to push back against the grip of the state on education. These efforts for greater autonomy and legitimacy would become engrained values in educators that would remain through the Russian Revolution. This progression can be seen through Patrick Alston’s work Education and the State in Tsarist Russia. Alston takes a chronological approach to depict the relationship between education and the state beginning in the 18th century through 1914. He divides his book to demonstrate the gradual but present growth of the influence of educators in Tsarist Russia.

- Brower, Daniel R. Training the nihilists: education and radicalism in Tsarist Russia. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1975.

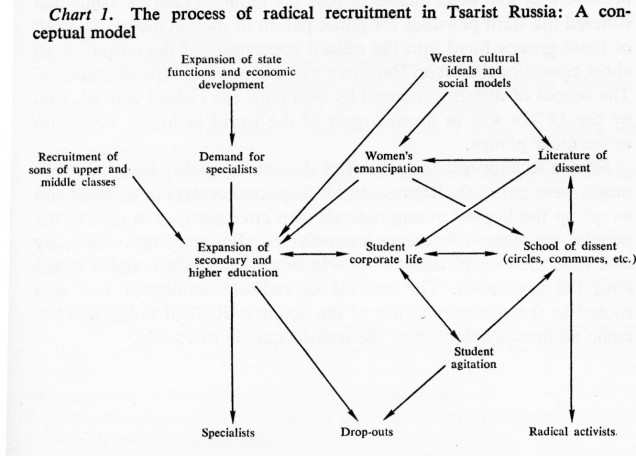

Daniel Brower’s work Training the Nihilists: Education and Radicalism in Tsarist Russia explains the role of formal education in the creation and evolution of radicalism in Russia during the mid to late 19th century. The book is broken up into chapters that focus at first on the smaller groups in Russian society like family and then places focus on larger groups concluding with a newly established society of dissenters. Dissent was a key ingredient in Russia during the late 19th century and early 20th century, this book aims at answering where this dissent came from. Two features of Brower’s work that are most helpful in gaining an understanding of dissent in Russia are survey date from 1840-1870s revealing the level of education for Russian radicals and a flow chart of the development of Russian radicals between 1840-1870.

- Kassow, Samuel D. Students, Professors, and the State in Tsarist Russia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

Early 20th century Russia was a period of full of different groups functioning as political actors influencing the nature of the Russian state. In Students, Professors, and the State in Tsarist Russia, Samuel Kassow focuses on the interactions of students, universities, and professors with the state. Kassow shows that failure of the tsarist Russian state to recognize the legitimacy of student movements based out of Russian universities. Officials of the state had to find a balance between limiting social unrest produced from universities and educational institutions while not completely crushing education as it was recognized the need for an increase of educated laborers. Professors and the Russian government clashed in ideological purpose for universities. Professors saw universities as models of free research and academic freedom while the government saw the establishment as utilitarian in purpose, raising proper civil servants. An electronic copy of the work can be found here.

- Seregny, Scott. Russian Teachers and Peasant Revolution. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1989.

Scott Seregny questions the notion of rural teachers as meek, humble, isolated figures in late 19th century Russia.Using accounts of rural teachers, students, and town officials he reveals that rural teachers while late the blossoming period of professionalism in Russia held particular power in organizing an All-Russian Teacher’s Union with strong political aims. To combat this perception of educators, Russian educators became a politically active minority pushing against the Old Regime of the Tsar. Russian teachers like other professions during the late 19th century and early 20th century desired self-definition and became aware that their desires could not be achieved in the current Tsarist system. The climax of the rural teachers’ political efforts occurred in 1905 with the 1905 Revolution but quickly faded with the passing of the year. Seregny dives into the low levels of respect towards rural teachers due to low pay, modest origins, and high levels of bureaucracy.

- Walker, Franklin A. “Enlightenment and Religion in Russian Education in the Reign of Tsar Alexander I.” History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Autumn, 1992), pp. 343-360.

Tsar Alexander I sought to educate his countrymen through a plan to expand public education drafted by Catherine II. The initial aim of this expansion of public education in Imperial Russia was to instill enlightenment ideals in the people of Russia but after the threats created during the Napoleonic wars these aims shifted to creating an obedient, moral society to prevent rebellion. During the years after the French Revolution many blamed a lack of religion as the cause of the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. Franklin A. Walker investigates the balance of religion and enlightenment in education under the reign of Tsar Alexander the I. The need for obedience reinforced the role of religion in education even as ideals of the enlightenment became increasingly popular in education resulting in unique approach to education. An electronic copy of the article can be accessed here.

- Stillings, Renee. The School of Russian and Asian Studies, “Public Education In Russia from Pete I to the Present.” Last modified December 8, 2005.

Renee Stillings offers a short history of Russian education from the 18th century to the present. Her work provides basic foundational knowledge that aids in later developing a larger understanding of the complexities of the Russia’s educational system. The webpage can be accessed here.

- Brooks, Jeffery. When Russia Learned to Read. (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2003), 54.

With the end of serfdom in Russia came an explosion of peasant desires for education. Jeffery Brooks presents the growth of peasant education during the late 19th century in his work When Russia Learned to Read. The basic components of education are covered including schools, teachers and curriculum. One of the most significant aspect of the work is Brooks’ analysis on the effects of peasant literacy, concluding the with greater amounts of literacy, the peasantry grew curious and ambitious, desiring a different life compared to their parents.

- Souder, Eric M. The School of Russian and Asian Studies, “Tolstoy’s Peasant Schools at Yasnaya Polyana.” Last modified November 18, 2010.

Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy serves as a example of an early education reformer in Tsarist Russia. Eric M. Souder provides information of Tolstoy’s efforts in education in the article “Tolstoy’s Peasant Schools at Yasnaya Polyana”. Tolstoy became upset with the format of education in Russia and Europe during the mid 19th century as he saw that it was not organic enough and non-conducive to learning. This belief mixed with sympathy for the peasant class of Russia provided Tolstoy the inspiration to form his own school in Yasnaya Polyana. His curriculum expanded further beyond traditional subjects to areas like singing, drafting, and Russian history. Souder’s thorough depiction of Tolstoy’s work in education reveals the attitudes surrounding education and the condition of education during Tsarist Russia. This webpage can be accessed here.

- Tolstoy, Lev. The Complete Works of Count Tolstoy: Pedagogical articles; Linen-measurer. Boston: Dana Estes & Company, 1904.

During his efforts to increase education for Russian peasants, Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy published several works on what he believed the be improvements in the field of education that would benefit Russia and in particular the peasants. He compared educational systems around the world to form his own ideal educational system that he asserted would serve Russia better than the current system. The comparative work conducted by Tolstoy was highly critical of the rigid and at times exclusive nature of European educational system. The American public educational system functioned as the embodiment of the ideal of mass education that Tolstoy strove for in Russia. The works of Tolstoy demonstrate a growing disapproval of the current system of education under the Tsars that would later erupt during the Russian Revolution. Many of the concepts put forth in his works would later emerge in experimental Bolshevik schools during the 1920s. The complete compilation of Tolstoy’s works can be found here.

- McClelland, James C. Autocrats and Academics: Education, Society, and Culture in Tsarist Russia.Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Inequality in the in quality and accessibility of education during Tsarist Russia is the thematic center of James C. McClelland’s work Autocrats and Academics: Education, Society, and Culture in Tsarist Russia. He asserts that the adoption of educational techniques like the gymnasium from German schools allowed for the development of a national culture but at the expense of widening the gap between social classes. The elite nature of secondary schools and universities during Tsarist Russia produced an intelligentsia that would be disconnected from the majority of Russian society in terms of level of education. This work reveals Tsarist relations with elite education, the pedagogy of elite academic institutions, and student activism.

Education During Early Revolutionary Russia

Revolution provided many educational reformers a time to shine and bring their experimental schools to reality. New educational ideologies and practices were incorporated into schools as new schools were established to provided education to the masses while others were created specifically for groups like proletariats or peasants. The formal curricula of these schools varied greatly due to many schools that were self administered by faculty and that evolutionary nature of education during Revolutionary Russia that constantly updated and shifted. Emphasis shifted from one area to another the focus one year may be instilling socialist ideals in student and in following years the focus may shift to science and technology.

- Pipes, Richard. Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

Richard Pipe enables readers of Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime to follow the systematic changes in education brought about by the Bolsheviks through a detailed chronology of educational change. Vladimir Lenin along with Anatolii Lunacharskii defined the mission for all educational institutions as to raise a new group of human beings superior in culture and intelligence. In 1909 an experimental Bolshevik school was established in Capri with help from Maxim Gorky and Fedor Shaliapin. The goal of this school was to created cadres of educated workers who would then assimilate with the rest of workers to spread their recently acquired knowledge. Lenin was a major opponent to this school because he did not believe that workers possessed the creativity needed for the creation of a new society. Soviet Russia viewed education as vospitanie,meaning upbringing in that education should serve as a means of developing a society of virtuous beings. The key emphasis of this education was science and technology to set the foundations for a technologically advanced Soviet Russia. By 1918 all education became nationalized under the authority of the Commissariat of Enlightenment. A new education system was established leading to a concise pathway from kindergarten to university. While this was a major change other radical philosophies like the establishment of farm and communal worker schools never came to fruition due to fiscal constraints.

- Gleason, Abbott, Kenez, Peter, and Stites, Richard. Bolshevik culture: experiment and order in the Russian Revolution. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Lenin recognized the need for a long term educational process, teaching the themes of socialism and political consciousness to society in order to build a socialist society. In Bolshevik culture: experiment and order in the Russian Revolution, education is described as a tool of the Bolsheviks to mold Russia. One means of mass education was printing of propaganda pamphlets but many simply could not read and those who could read responded to the state produced material with disgust. During the Provisional Government, soviet representatives attacked the Ministry of Education for excessive amounts of bureaucracy, lack of progress to increase literacy, failure to increase the status of teachers, and failure to update curriculums to incorporate revolutionary culture. A means of effective communication with the masses came with the popularization of cinema. Authorities were able to produce revolutionary teachings without any words at all through the medium of cinema.

- Rosenberg, William. Bolshevik Vision: First Phase of the Cultural Revolution. (Ann Arbor: Ardis Publishers, 1984), 287.

The Bolshevik ideology is broken down into several sections of society in William Rosenberg’s work Bolshevik Vision: First Phase of the Cultural Revolution. His descriptive writing allows for a vivid depiction of Bolshevik ideology. A section of book titled “United Labor Schools: The Nature of a Communist Education” covers the topics of primary, secondary, and higher education with great detail. Several different school models are described at the primary and secondary level including the United Labor School, the factory school, and the polytechnic school. Higher education is also covered as the nationalization of universities is chronicled, exposing great resistance from the professorate against Lunacharsky’s reforms.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Cultural Front. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992.

Sheila Fitzpatrick writes on the cultural revolution in Russia by observing the many dynamic groups and forces that transitioned revolutionary Russia to conservative Stalinist Russia. In her work she analytically depicts the troubles faced by the Bolsheviks in establishing a new education system for the newly created socialist society. The two chapters, ‘Professors and Soviet Power’ and ‘Sex and Revolution’ in The Cultural Front provide deep insight into the struggle for power in education in the new socialist society as intelligentsia were initially removed from education by replaced with frequency. The chapter ‘Sex and Revolution’ uses student health surveys to demonstrate the attitudes of proletariat workers in educational institutions. These attitudes included aversion towards bourgeois professors, apathy towards bookwork, and conservative sexual relationships with peers.

- McClelland, James. “Bolshevik Approaches to Higher Education, 1917-1921.” Slavic Review . no. 4 (1971): 818-831.

During the years 1917 to 1921 the Bolshevik government faced multiple military threats from Imperial Germany, White Russian armies, and movements for national independence. Despite the numerous amount of issues at hand the Bolshevik government was still able to devote time and energy to the revolutionary agenda including educational reform. James McClelland researches three major experimental education systems during this revolutionary period.The first of these initiatives was under the authority of Narkompros which aimed to increase accessibility to higher education, increase enrollment of working class students, and utilize a Marxist agenda. Economic, military, and political strains of the Civil War forced the Bolshevik government to approach educational reform from another angle. The new route to reform in education centered on the vocationalization of education and militarization of students. With the New Economic Plan came a third form of educational reform. This third plan sought to centralize higher education under the authority of the government. McClelland focuses on the relationships between the Bolshevik government and the professors of universities to reveal the complex nature of higher education in revolutionary Russia. An electronic copy of McClelland’s work can be accessed here.

- Rosenberg, William. Bolshevik Visions: The First Phase of the Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia. Michigan: Ardis Publishers, 1984.

The drive and enthusiasm Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky possessed during the early period of Bolshevik Russia is capture in William Rosenberg’s work Bolshevik Visions: The First Phase of the Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia. The work provides a detailed introduction into aims of a new Soviet school that would break away from all of the pervious bourgeois educational institutions. Factory Schools and United Labor Schools were the educational platform set out by Lunacharsky who was eager to aid in creating the new soviet citizen. The work then continues with several speeches by Lunacharsky including his 1918 “Speech to the First All-Russian Congress on Education”, “Basic Principles of the United Labor School”, and “Students and Counter-revolution”. Each of these writings from Lunacharsky show a genuine conviction to change society through education to create an entirely different culture.

- Finkel, Stuart. On the Ideological Front : The Russian Intelligentsia and the Making of the Soviet Public Sphere. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Higher education proved to be one of the last institutions to fall to the control of the Soviets as remnants of the intellectuals’ authority remained. The final push came from the “harsh line” mentality towards universities in that all bourgeois figures and institutions must be removed. Narkompros and Anatoly Lunacharsky contributed to the state seizure of higher education by advising the Party Central Committee of the need to reform higher education. In the way of this desired change was Valdimir Lenin, he believed that there was no need for the immediate take over of universities as the proletariat did not need a high level of education. Lenin’s stance towards higher education was replaced by the “harsh line” when in 1921 a committee was established to discuss reforms of universities.

Education During Early Soviet Russia

As the Bolshevik and Soviet control of Russia solidified came an increased need to maintain this current state and to promote state ideologies. Education became a necessity for the proletariat as the need for an educated proletariat was announced by the state. This period of educational development face a multitude of challenges as the student body rapidly changed from elites to proletariat and peasant students. To extend mass education to proletariat and peasant students by giving these groups preference into secondary schools and universities would lower the standard of education which then would result in the product of a workforce that has received a mediocre education. Educational institutions took the form of vocational schools that set students up for higher education aiming to produce an educated workforce like that never seen before in Russian history. A major problem for educational reforms during this period was parental attitudes towards education as many parents felt that the recently deposed form of education that focused on reading, writing, and arithmetic was proper in curriculum.

- Lipset, Harry. “Education of Moslems in Tsarist and Soviet Russia.” Comparative Education Review. no. 3 (1968): 310-322.

A major shift occurred in the treatment of Muslims in Russia from the Imperial state to Revolutionary and Soviet Russia. Discrimination of minorities during Imperial Russia was commonplace and left Muslims in Russia with insufficient and inadequate education. This limited education for Muslims was improved during Revolutionary and Soviet Russia due to the socialist ideal of universal education. Harry Lipset covers this topic in “Education of Moslems in Tsarist and Soviet Russia”, contrasting the condition of Muslim education under Tsarist Russia and post-Tsarist Russia. To add depth to his work he analyzes the official treatment of other minorities such as Ukrainians and Armenians under each government. Lipset asserts that Muslims were able to make large advances in culture and education through the socialist ideals introduced through the collapse of Imperial Russia. An electronic copy of the article can be accessed here.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Commissariat of Enlightenment; Soviet Organization of Education and the Arts Under Lunacharsky, October 1917-1921. Cambridge: University Press, 1970.

The Narkompros was Soviet commission on enlightenment tasked with creating and improving art and education in the newly formed socialist Russia. Sheila Fitzpatrick devotes several chapters to the reformation of education under the authority of the Soviet. Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky, the commissar of Narkompros set out a multitude of doctrines and declarations that would shape the new educational system in the socialist society. For example, one Lunacharsky’s declarations set up primary and secondary schools so that teachers left to their own devices to organize and operate schools. Fitzpatrick’s work provides a vivid chronology of educational changes that occurred due to the influence of Narkompros.

- Levin, Deana. Soviet Education Today. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1963.

Deana Levin approaches education in the Soviet Union using the historical background of the Russia since 1917. Unlike other works on Soviet education, Soviet Education Today does not compare Soviet education with American education but rather researches the aims and methods of the system. To explain how the Soviet educational system works Levin uses official documents and statements swell as personal observations from trips to the U.S.S.R. where interviews with students, educators, and administrators were conducted. Further insight is provided from Levin’s experience as a school teacher in Moscow for five years before the outbreak of World War Two.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. Education and Social Mobility in the Soviet Union 1921-1934. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

One of the most comprehensive works on education in socialist Russia, Education and Social Mobility in the Soviet Union 1921-1934 by Sheila Fitzpatrick provides a wealth of knowledge on the changing educational system in Russia between 1917 and 1934. Her work covers a large spectrum from ideological changes in education to the salaries of educators. The book is structured in a chronological format to follow the new socialist Russian state as it develops and changes. Although a larger variety of topics are covered in her work, Sheila Fitzpatrick centers her writing on education as a means of social mobility in the newly created socialist society.

- Bereday, ed. The Changing Soviet School. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1960.

The Changing Soviet School provides a wealth of information on education in Russia with chapters devoted to major phases of Russian history beginning with Tsarist Russia and concluding with the Soviet Union. The claims presented in the work are supported by the research of 70 American researchers who visited and toured soviet schools, universities, collective farms, and industrial plants in 1958. To provide complete research of the evolution of education in the U.S.S.R. the book presents education during Tsarist Russia, Revolutionary Russia, and the Soviet Union. The work is divided into three sections that all provide detailed insight into Russia education. Part one focuses on ideological, social, historical, and philosophical characteristics of Russian education to analyze pedagogy. Part two describes the formal institutions of preschool, primary school, secondary school, and university inquiring as to what content was taught, how content was taught, and how teachers were trained. Part three questions the universal nature of universal education by studying marginal groups like talented and handicapped students. The purpose of the work is twofold, first two provide a detailed image of the Soviet educational system and second to illuminate similarities between the Soviet system with the American educational system.

- Gorsuch, Anne E. Youth in Revolutionary Russia: Enthusiasts, Bohemians, Delinquents. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Anne Gorsuch looks into the experiences of youth in Russia during the New Economic Policy. The economic challenges created by NEP left many children with no adult supervision when returning home from school. This situation caused largely by NEP resulted in limited many children to only four years of education before joining their parents in some form of work. Education for girls during this period was seen as too expensive so many parents kept daughters at home to work in the house and help raise younger children. Gorsuch provides insight into the role of gender in education for Russian youth for example, out of every one hundred days, males had 230 free hours and the females just 169.27. In addition to the role of gender in education she also provides important analysis of the influence of experimental forms of education. Entrance exams from secondary schools and universities demonstrated that students being taught at experimental schools were politically illiterate due to the ineffectiveness of the educators of these experimental institutions. These failures resulted in a relapse in curriculum from social behavior education to traditional history, economics, and political theory.

Scenes of Soviet Education from 1921:

Three communist Dutch school teachers went to Russia to observe the labor schools that had been created in the recently reformed Russia. They observed schools that taught toddlers up to adolescents. In these schools children were taught how to develop photographs, how to spin fabrics, how to use printing presses, how to work in a saw mill, and how to work in a laboratory. Each of the Dutch researchers wrote small biographies that can be found below. The observations of these three socialist educators serves as a gateway into the minds of socialist education.

Jan Cornelis Ceton: Opposed book oriented education. Favored taking students for nature walks to embrace the world. He opposed Christian education as it only served as a means of maintaing the current social order. He saw no need for administration in education as it created authoritarian figures. In 1919 he co-founded the Communist Teachers Association. He published several works on new education in socialist journals such as The New Era, two of these works are listed below. Both of these works demonstrate Ceton’s desire to incorporate socialist values into the education system in Holland and later around the world.

Ceton, Jan Cornelis. “Free school or compulsory state school” The New Era, (1902): 37-51, 109-121.

Ceton, Jan Cornelis. “Social Democracy and Education ” The New Era, (1913): 875 – 889.

Jan Cornelis Stam: Born in 1884 he grew up in a Calvinist family that placed heavy emphasis on education. He attended school at Sliedrecht, in South Holland where he was exposed to socialist values from some of his peers and teachers. He began teaching in 1903 and would later join the Social Democrat Party in 1909. He worked as an editor of the party newspaper The Tribune writing on socialist values in education and the neutral or co-ed school.

Willemse Wiljbrecht: A school teacher in Amsterdam from 1925 to 1940. Beginning in 1932 onward Willemse was a major figure in the creation and workings of the Marxist Worker Schools. She worked at Montessori Training for Teachers in Utrecht from 1940-1941. Willemse worked as the editor of Montessori Education from 1939 -1956. Many of her works were published in Renewal of Education and Montessori Education.

Wiljbrecht, Willemse. “Our Children Will Be Our Judges”

Below are scenes captured by Jan Cornelis Ceton, Jan Cornelis Stam, and Wilemse Willjbrecht during their travels to the Russia during 1921. These images expose the experimental nature of education during revolutionary Russia as students can be seen playing sports, acting in plays, and even chopping wood.

- Ceton, Jan. and Stam, Jan, and Wiljbrecht, Willemse. Soviet Education 1921. The International Institute of Social History. Accessed October 25, 2013.

Education During the Mid 20th Century Soviet Union

- Benton, William. Teachers and the Taught in the U.S.S.R. Kingsport: Kingsport Press, 1965.

Serving as a detailed analysis of Soviet education, William Benton’s Teachers and the Taught in the U.S.S.R covers specific areas such as film in education and the structuring of primary and secondary schools. Research from Benton’s 1964 trip to Moscow serves as the data for the majority of his book. The work uses a narrow lens in addressing Soviet education by focusing on particular areas and should be read as a supplement to works that take on the topic of Soviet education from a wider angle.

- Matthews, Mervyn. Education in the Soviet Union. London: University of Surrey, 1982.

With the changing of leadership in the Soviet Union would come changes, some transitions would bring more change than others. In Education in the Soviet Union, Mervyn Matthews compares education under the administration of Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev. His comparison focuses on general education, technical schools, and higher education looking into characteristics like teachers’ attitudes, student well-being, and problems in administration. Much of this works looks into the societal shifts that occurred after Joseph Stalin’s death.

- Grant, Nigel. Soviet Education. New York: Penguin Books, 1979.

A brief overview of education in the U.S.S.R. during the 1960s can be found in Nigel Grant’s Soviet Education. In his work he aims to present the educational system of the Soviet Union using first hand accounts of students and professor from the U.S.S.R. to supplement statistical information, official documents, and scholarly journals. He presents the general characteristics of primary, secondary, and higher education covering ideology, structure, staffing of schools, and discipline. Grant draws connections to other educational systems from other nations in his description of the workings of Soviet education.