Lee Kye-jun: A Life for Freedom

One day in 2010, a few theological professors in South Korea gathered together to discuss current trends in theology and the contexts in which churches found themselves. During the informal meeting, the question surfaced: Who made a decent achievement in balancing theology and church work? They concluded that the Rev. Lee Kye-jun was the person who best fit the category, and they decided to express their gratitude for his Christian leadership in Korean Society. Therefore, in honor of Lee Kye-jun’s eightieth birthday in 2011, a commemorative event was held in the Luce Chapel of Yonsei University. Many theologians and pastors dedicated a book to him, Shinhak eui Gil, Mokheoeui Sam [A Road of Theology, and A Life of Ministry].[1] The book contained some of Rev. Lee’s articles that had appeared in academic journals, as well as articles about him written by others. The celebration and the book bespoke the influence Lee exercised as a minister of the gospel who pursued justice and freedom, even at the expense of his own position in the church and the academy.

- A Web of Human Relationships

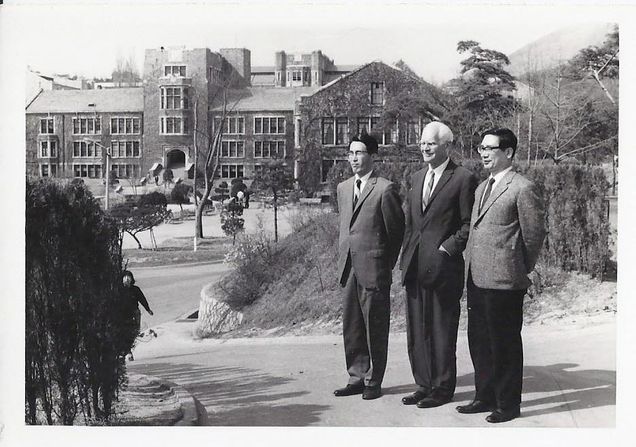

Rev. Lee Kye-jun is best known for his contribution to campus and church ministries. He served as a professor and a chaplain at Yonsei University (1964-97) and as a pastor at Sinbanpo Methodist church (1982-1997, as a preaching pastor; 1997-2004, as a pastor; and 2004-present, as the senior pastor). But he has also been deeply engaged in the department of theological education for the National Council of Churches in Korea (NCCK), served as a member of the committee for the Methodist reformation, participated in a Wesleyan theological group, worked in a theological association that explored Korean culture, and joined a civic organization that sought for convenient facilities for the disabled. His work and studies were not restricted to one area, though the various aspects of his career could be united around a common theme. Lee always pursued freedom through justice.

His dedication to freedom sometimes came at a price. In the middle of his chaplaincy at Yonsei, Lee had to resign his professorship (1975-80) due to the military government’s displeasure with his work. At other points in his career, he sometimes sacrificed his ambitions. When he was offered leadership positions, he did not automatically take them. Instead, he carefully considered what he could contribute as a leader. If he concluded that he had the ability to enrich the common good then he would accept the post, otherwise Lee declined. This was most potently illustrated in the Sinbanpo Methodist church. Lee was only willing to accept the role of senior pastor after he had served as a preaching pastor for fifteen years.

In 2005, Rev. Lee wrote his autobiography Freedom that Bears Hope and organized it around numerous episodes in his life. He revealed that the various episodes involved many different human relationships. Thus, Lee stated that his life simply was not his own achievement, but largely the product of interactions with others.[2] Some of the encounters in his life, including those with his family, led him to play an important role in Korean churches and society.

Lee Kye-jun was born in Pyeongyang, North Korea in 1932. In his childhood, his father, Lee Changho, greatly impacted his personality and Christian faith. Lee Changho graduated from Pyeongyang Theological Seminary in 1930, and finished a second degree there in religious education in 1932. Before he was a student at the seminary, he had acted as a fundraiser for the independence movement, working against Japanese imperialism. The Japanese officials who were in charge of the Gamulnam district in North Korea were angered by his actions, and sentenced Lee Changho to seven years in prison. He was released on parole after four years (1920-1924).[3] Afterwards, Lee Changho pastored Namunbak church for a long time. [4] He also managed a school for the blind and mute (1936-48).[5] Lee Changho served as the president of the school which met in the memorial hall of missionary Samuel Moffett, and he worked with Moffett to strengthen the institution. The school became widely known in Korean society, so when a deaf-blind author Helen Adams Keller came to Korea in the 1930s she paid a visit to the school.[6]

Certain parallels can be seen between Lee Kye-jun’s career and that of his father. Lee Changho fell afoul of the government authorities and was imprisoned. His son, Lee Kye-jun also crossed the military government and was forced out of his job. Lee Changho worked with the blind and mute, and Lee Kye-jun took up the cause of the disabled. Both men displayed courage and compassion throughout their lives.

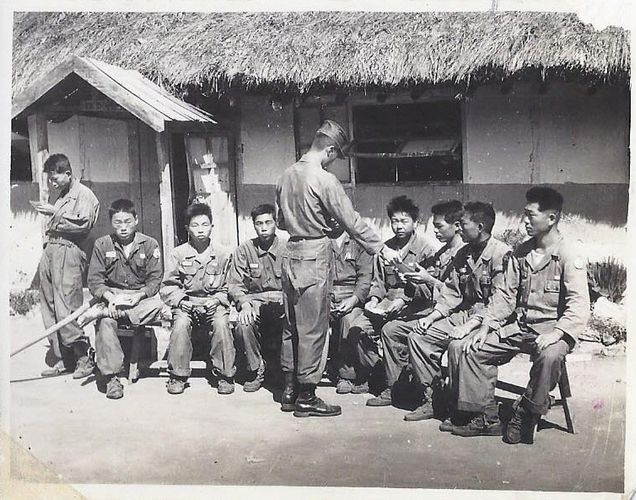

Another important person in Lee Ke Joon’s life was Pak Daeseon), who was a president of Yonsei University. Their relationship started at Sunghwa Theological School, a Christian high school in Pyeongyang. Lee moved to Sunghwa School because he was tired of communist education. At the time, Pak was the vice-principal of the school. Later, Lee met Pak again at Methodist Theological Seminary (currently, Methodist Theological University). This time Pak was Lee’s professor.[7] During the Korean War, MTS had to move to Busan, in the southern part of Korea. The seminary was buzzing with new ideas. Lew Hyungki, who was principal of the seminary, amassed a group of professors who had studied abroad, such as Hong Hyeonseol, Yun Seong-beom, Kim Yongok, and Pak Daeseon. They began introducing the ideas of Karl Barth, Rudolf Bultmann, and Reinhold Niebuhr to the students, as well as new ideas about the Bible based on what was emerging from the Qumran documents. The mix was intoxicating, and it shaped the Korean leadership of the post-war period. Students such as Jeong Chae-Sik and Lee Kye-jun graduated from MTS, and took contemporary scholarship with them. Lee first served as a military chaplain for four years. But through the intercession of Pak Daeseon, Lee Kye-jun went to the Boston University School of Theology (BUSTH) in August 1961. A Fulbright scholarship helped pay for his airplane ticket, and Boston University offered him a scholarship that covered tuition and housing costs. After finishing his S.T.M. degree at Boston University, he served the Frankfort Methodist church in South Dakota for four years, but returned to Korea to work as the chaplain at Yonsei University by the request of Pak Tae Sun.

- Harmony between Church and Academy

The experience of living in diaspora, which involves being geographically dispersed, impacts the lives of immigrants. Erik Olsson argues that immigrants tend to maintain “a sense of their own ethnic/diasporic identity” in their new homes, and often actualize their orientation to their homeland by returning to their home countries.[8] To live in diaspora causes people to live in a complicated matrix. They must navigate the sometimes competing or even contradictory dynamics of their home culture and their host culture, particularly as they work through human relationships, cultural expectations, and socio-political realities. Similar to this, when immigrants return to their home countries, they often introduce new dynamics into their society, sometimes for good and sometimes for ill.

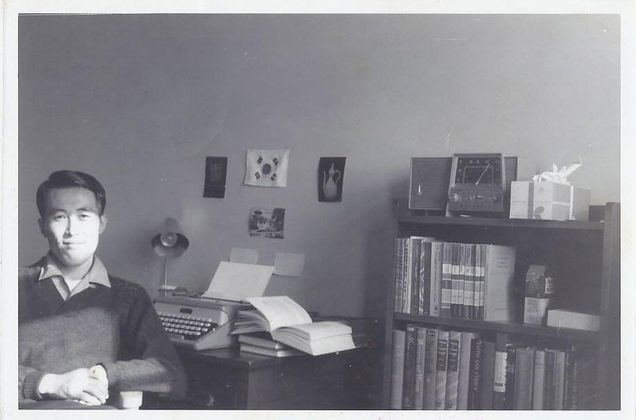

Joining the Korean diaspora in Boston opened Lee Kye-jun to a new stage in his life. For one thing, his studies at Boston University expanded his theological horizons. Under the guidance of Prof. L. Harold DeWolf he studied systematic theology and Christian social ethics. In addition, the preachers at Marsh Chapel at Boston University introduced to him new ministerial traditions. Dean of Marsh Chapel Howard Thurman, for example, exposed Lee to the contemplative and mystical side of Christianity. Lee also attended chapel services at Harvard University where he heard famous theologians like Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr. But it was a class with philosopher Paul Schilling that left the deepest impression. Schilling led a seminar on “Contemporary theologians.” He encouraged students to choose a theological question and then to explore the idea in one of ten suggested contemporary theologians. Each week a different student would present his or her findings, and then the whole class joined in a discussion. The experience had two important consequences. First, it allowed Lee to move beyond the Barthianism that he had absorbed at MTS when he wrote his thesis on Karl Barth’s Christology.[9] Second, it shaped his own pedagogy. When he returned to Korea and began teaching at Yonsei University, Lee employed a similar style of instruction. He learned, however, that the Korean students were very uncomfortable with the format. It reminded him that culture and pedagogy are related to one another.[10] He had to shift his method of teaching. What he did not change, however, was his aim for holistic education. After his years at the Boston University School of Theology, Lee concluded that the deep interest that professors like Paul Schilling, Walter G. Muelder, Donald Maynard, and Paul E. Johnson showed for the Korean students was an image of holistic theological education. They not only cared for the students’ minds, but also their hearts.[11] He strived to practice that kind of holistic education at Yonsei University.

While he was at Boston University, Lee Ke Joon intersected with other Korean students. Most notably, he studied alongside a future United Methodist pastor Ham Seong-kuk, a future professor at Ewha Pak Won-ki (a former chaplain and a professor at Ewha Women’s University), and a future filmmaker Kim Dae Sil.[12] Lee, Ham, and Kim went to the same church, the First Korean Church of Boston. In 1961, the Korean church had stopped its worship, but one year later ten people gathered together to restore it. They asked Rev. Lee to become the pastor of the church, but he suggested that the church operate through a committee rather than depending on a senior pastor. The church met twice a month, and about forty or fifty people attended. Although some members were not Christian, they came to the church to meet with other Korean people.

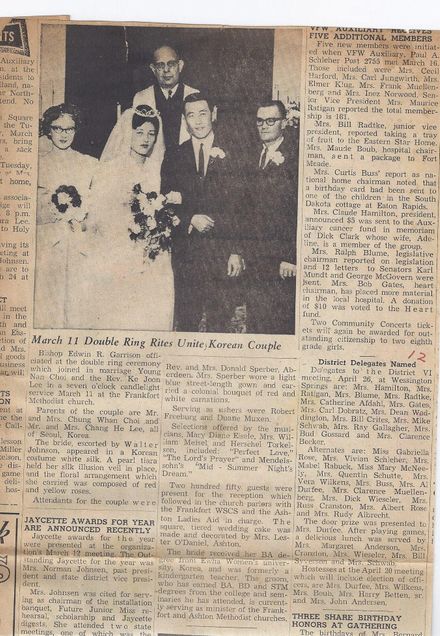

After the graduation, Lee ministered in the Frankfort Methodist church in South Dakota. Lee had been engaged to Choe Yeong-nan before he had moved to the United States. The couple was eager to marry, but Choe could not get an F-2 visa. Finally, members of the church approached their senator, George McGovern, and through him obtained the necessary documents. Lee Kye-jun and Choe Yeong-nan were married in South Dakota, with the Bishop Edwin R. Garrison presiding.[13]

The experience at the First Korean Church in Boston and in the Methodist Church in Frankfort, South Dakota, convinced Lee of the vital role lay people play in a congregation. Although many churches in Korea depend on the leadership of a senior pastor, Lee made sure that in the Sinbanpo church, where he served for many years, a lay committee headed the administration of the church.[14] He rejected pastor-centered ministry. Instead, he focused on theological education for lay people, inviting many theological scholars to address the congregation, and encouraging church members to read theological books together.[15] Furthermore, Sinbanpo church became a part of small church movement that attempted to remain small in size, purposefully eschewing the mega-church movement, while intentionally practicing love for their neighbors.[16] In fact, the church spent more than thirty percent of its whole budget to help disadvantaged groups, such as the blind, tuberculosis patients, and financially insecure churches in rural areas.[17] In this way, the Sinbanpo church became a model for other congregations that wanted to practice social service for the alienated and the marginalized.

The time Rev. Lee Kye-jun spent in the diaspora shaped his ministry. It affected his teaching and his understanding of the church. The dynamics of the diaspora enriched his life in the church and the academy.

- A Hope for Freedom

When Rev. Lee Kye-jun was about to publish his autobiography, the president of the publishing company, Jeong Deok-ju, suggested he entitle it, Freedom that Bears Hope. Lee agreed to the idea. If one has to summarize his life in a word, it would be a life for freedom. He said, “Although unwanted pressure and external forces restrict or limit people’s freedom, no one can stop the people’s will for freedom. Humans can creatively think something, have authentic relationship with others, and grow to be responsible persons. Humans can only find the meaning of existence and seeds of hope in freedom, so that freedom is the beginning point of life for hope.”[18] His notion of freedom is different from self-indulgence. The freedom Lee speaks of happens in the coram Deo (the presence of God), a truth he illustrated by walking a path of justice even in the midst of oppression and injustice.

As mentioned above, Rev. Lee was forced to resign his position at Yonsei University by the military government, and he spent 1975 to 1980 unemployed. Although the government never gave a specific reason for his dismissal, it is easy to guess why he curried the state’s disapproval. First, as chaplain Lee invited many people to preach whom the government had marked as troublemakers. Second, Lee was in charge of SCA (KSCF: Korea Student Christian Fellowship), an ecumenical Christian organization for youth. The SCA played a leading role in anti-government movements and in student groups, so that the SCA leaders became a target of government surveillance. The close ties between Lee and the SCA were exemplified in his relationship to Oh Myeong-ryul, a student imprisoned for leading a protest. Rev. Lee asked a high-ranked police officer to release Oh. The officer agreed on the condition that Mr. Oh remain in a state of house arrest in the home of Rev. Lee. Third, Lee’s relationship with the president of Yonsei University, Pak Daeseon, was problematic to the government. In 1974, a nation-wide movement against the government formed, with about one hundred universities participating. Two professors from Yonsei University, Kim Dong-gil (history) and Kim Chan-kuk (theology), as well as a few students from the school were arrested along with more than one hundred others. They were all charged with the Minchunghakryun crime, and imprisoned for being communists with the rebellious intent to subvert the nation. When the two professors were released in 1975 after ten months in prison, Pak Daeseon welcomed them back to Yonsei University, and reinstated them with a big celebration.[19] His actions prompted the government to dismiss Pak Tae Sun from being president of Yonsei University in April 1975, and they also fired Kim Dong-Kil (history), Kim Chan-kuk (theology), Seo Nam-dong (theology), and Yang In-eung (computer science). [20] Two months later, Rev. Lee also had to leave Yonsei University by the order of the government. Upon his exit he held his head high: “The authorities in the government saw my behavior as crimes, but on the basis of my faith and conscience they were not sins. Rather, the works were my response as a pastor to God’s calling and my responsibilities as a chaplain to Yonsei University. Thus, I could leave campus with a serene mind.”[21]

Five years of unemployment were difficult for Lee Kye-jun, but he did not waste the time. In those days, to be dismissed by the government meant to be socially ostracized. If anyone dared to interact with “seditious” characters, they risked getting in trouble too. Thus the churches, which had invited him to preach or lecture before, did not contact him anymore. A few people, such as Kang Won-yong, Eun Jun-kwan, Kim Hu-geun, and Jeong Yeong-kwan took the risk of inviting him, but most avoided any affiliation with Lee. Sometimes he confessed to feeling depressed; nevertheless, he did not give up.[22] Rev. Lee translated many books. He worked on making many of the writings of John Wesley available in Korean. He also translated Collin Williams’s Theology of John Wesley; Paul Tillich’s Ultimate Concern, and Culture and Religion; and Helmut Thielicke’s The Waiting Father and Christ and the Meaning of Life.[23] In addition, he wrote some of his own books: The Korean Church and the Missio Dei, Silence of God, Martha Complex, and Living Together.

Lee became one of the founders of Chongheoi Methodist Theological School, an unauthorized theological school that operated outside the control of the government. A few Methodist pastors gathered and invited him to start the school. Together, they gathered the various Christian professors dismissed by the government from leading universities like Hanshin, Kyunghee, Yonsei, Korea, Junbuk, and Seoul National University. Some faculty also came from Presbyterian Theological and Methodist Theological University. The school opened in 1976. Although it could not offer an official degree, Chongheoi had a stronger teaching staff than any other theological school. In 1978, Lee went to Emory University and finished his D.Min. degree in two years, through a joint program between MTS and Emory University.

Lee was also involved in strengthening the Methodist church in Korea. He served as the chairperson of the reformation organization. He reluctantly accepted the position because he disliked church politics; however, he finally took the position by popular demand, judging that maybe he could contribute something to Methodist churches. Among other things he suggested the Methodist church embrace a two-year episcopacy instead of a four-year term in the office; increase the ratio of representative women pastors in an annual conferences; and galvanize the role of lay people. Lee’s ambitious agenda achieved partial success.

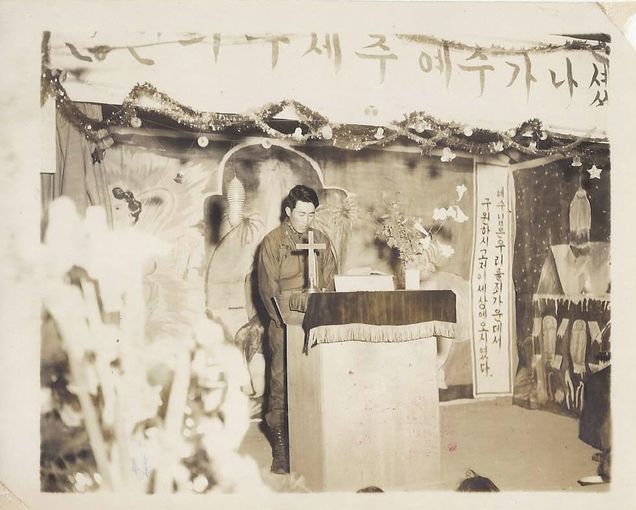

Before he served at Sinbanpo Methodist church, Lee had many ministerial experiences. He had served as a military chaplain, a pastor in the Dakota plains, and as a university chaplain. He was especially influential in the latter role. Lee believed that a university chapel was a temporary place, not a regular church. While the liminal space of the university chapel had drawbacks, Lee capitalized on the opportunities. He pursued new types of worship appropriate to students. He laid down some key guidelines and principles for the chapel of Yonsei University: 1) Chapel should be for both Christians and non-Christians; 2) Preachers could be pastors or lay persons, but they should all be people who approach students intellectually; 3) Worship services can take diverse and creative forms; 4) The message preached should be based on the Christian principles of justice, freedom, love, and hope in the midst of unjust and restricted social structures; 5) The first goal of chapel should align with the spirit of a university, which is a place that pursues higher education according to the Christian spirit. Pak Jonghyeon, a lecturer of Myongji University, has said that these principals were adventurous and experimental under the military dictatorship.[24] The result was a chapel that was known for incorporating monodrama, shadow acts, music performances (including Korean traditional music performances), and conversational preaching during the 1970s.[25]

His vision was distinctly different from most Korean churches of the time. They emphasized the growth of churches in terms of quantity during the 1970s; Lee pursued quality, trying to cultivate healthier churches by taking care of a community and its people. While most Korean churches preferred the charismatic leadership of a senior pastor who had authority to manage a whole system of churches, Lee followed a different path. His pastoral philosophy rejected autocratic leadership, and emphasized partnerships with community members. The trend he began in Boston and South Dakota, carried into Yonsei University, and finally into the Sinbanpo Methodist church as well.[26]

The Korean word for teacher is “Seonsaeng (先生).” It combines the two Chinese characters, ”previous” and “life.” That is, teachers are the people who first model for others an authentic life, not only teaching with their words but also with their actions. In this sense, Rev. Lee Kye-jun is a genuine teacher for many people. The book Shinhak eui Gil, Mokheoeui Sam [A Road of Theology, and A Life of Ministry] is but one proof of that fact. It stands as a sign that his personality and life attracted many people, and numerous Korean Christians have volunteered to follow his example. In that way, Lee Kye-jun has been an authentic teacher for the people who attempt to contribute to both church and society today.

Written by Heuiseung Lee

Edited by Daryl Ireland

[1] Dr. Jung Bae Lee and Dr. Won Kyu Lee at MTU (Methodist Theological University), Dr. In Chul Han and Dr. Sang Keun Kim at Yonsei University, Rev. Jong Hyun Park, Rev. Baek Gul Sung, Rev. Hak Chun Lim, Rev. Won Young Son, Rev. Seung Woo Jung, and Rev. Hyung Suk Nah in churches dedicated this book with their articles, which illuminated Rev. Lee Ke Joon’s life.

[2] Lee Ke Joon, Heemangeul nahneun Jaui “Freedom that bears hope” (Seoul: Handul Press, 2005), 6.

[3] Lee Ke Joon, Heemangeul nahneun Jaui “Freedom that bears hope,” 294-95.

[7] Lee Ke Joon, Heemangeul nahneun Jaui “Freedom that bears hope,” 79-85.

[8] Erik Olsson and Russell King, “Introduction: Diasporic Return” Transnational Studies Vol. 17 (3) (Winter 2008): 255.

[9] Jung Bae Lee concluded that this theological shift was a “seed of another hope” in Lee Ke Joon’s life. In Chul Han and Won Young Son eds., Shinhak eui Gil, Mokheoeui Sam “A Road of Theology, and A Life of Ministry”, (Seoul: Dongyeon Press, 2011), 168

[10] Lee Ke Joon, Heemangeul nahneun Jaui “Freedom that bears hope,” 96.

[12] Lee Ke Joon, Heemangeul nahneun Jaui “Freedom that bears hope,” 94. See the entry on Dr. Dai-Sil Kim-Gibson at Boston Korean Diaspora Project [https://sites.bu.edu/koreandiaspora/individuals/boston-in-the-1960s/dai-sil-kim-gibson-documenting-life-in-diaspora/]

[14] Won Young Shon, “God’s Praxis and Educational Ministry at Sinbanpo church, Korea,” Kidokkyo Jungbo Journal Vol. 27 (December 2010), 342.

[15] Lee Ke Joon, Heemangeul nahneun Jaui “Freedom that bears hope,” 191

[16] Kyunghyang newspaper introduced Sinbanpo church as the first lay person-centered organization in Korea. See the website newpaper archive, http://newslibrary.naver.com/viewer/index.nhn?articleId=1987062000329210001&editNo=3&printCount=1&publishDate=1987-06-20&officeId=00032&pageNo=10&printNo=12839&publishType=00020

[17] See the article in Kyunghyang newspaper (March 21, 1986) See the website archive, http://newslibrary.naver.com/viewer/index.nhn?articleId=1986032100329207001&editNo=2&printCount=1&publishDate=1986-03-21&officeId=00032&pageNo=7&printNo=12456&publishType=00020

[18] Lee Ke Joon, Heemangeul nahneun Jaui “Freedom that bears hope,” 7.

[19] Lee Ke Joonn, Heemangeul nahneun Jaui “Freedom that bears hope,” 231-235.

[23] In Chul Han and Won Young Shon, eds., Shinhak eui Gil, Mokheoeui Sam “A Road of Theology, and A Life of Ministry,” 178.

[24] In Chul Han and Won Young Shon, eds., Shinhak eui Gil, Mokheoeui Sam “A Road of Theology, and A Life of Ministry,” 196

[26] In Chul Han and Won Young Shon, eds., Shinhak eui Gil, Mokheoeui Sam “A Road of Theology, and A Life of Ministry,” 199-202