Kim-Gibson Dae Sil: Documenting Life in Diaspora

- Growing Up in the Midst of Korean Turmoil

Kim-Gibson Dae Sil is a well-known independent Korean/American filmmaker and writer. She was born in Sincheon, Hwanghae Province, North Korea in 1938. At the time, Korea was under the colonial administration of imperial Japan. At the same time, Christianity was rapidly spreading on a national scale and it became a major factor in the modernization of Korea.[1] The great revival movement in Pyeongyang in 1907, in particular, had a significant impact on Korean society.[2] Prior to the arrival of Christianity, Confucianism dominated Korean culture, and it promoted Namjonyeobi (predominance of man over woman). However, Christianity eroded that cultural assumption, and created the idea of sin yeoseong, a “new woman.” In the 1920s and 1930s, the first generation of modern educated women appeared.[3]

Kim-Gibson Dae Sil was a sin yeoseong in Korean society. She was raised in a family committed both to the independence movement and the Christian faith. Kim Dae Sil’s grandfather, Kim Yong-je, was the founder of Yang San elementary school, an institution that fueled the independence movement in Anak, Hwanghae Province. He and the well-known independence activist, Kim Gu, were among the Christians working against Japanese colonialism.[4] They were arrested and imprisoned in Seodaemun Prison.[5] When they were in jail together, the two men talked about their precarious future. Kim Gu was distressed that if something happened to his life, he had no son to succeed him. At that time, he had only a daughter. So, Kim Yong-je suggested that Kim Gu adopt his third son, Kim Mun Ryang. The son whom they talked about was the father of Kim Dai Sil. Her father received advanced education in Japan and became a successful businessman.[6] Her maternal grandmother, Choe Dae-hyeon, was raised in the upper-middle class, became a widow in her mid-30s and raised her only child. She was a first generation Christian, and eager to educate her daughter. Thus, Kim Dae Sil’s mother, Yeun Sik-bae, received the best possible education from Seomun Girl’s middle and high school, and entered Ewha Women College (Currently, Ewha Womans University).

After Kim Dae Sil’s mother was married to Mun Ryang, her maternal grandmother made her son-in-law the head of the household and helped him in every possible way to flourish in his business ventures. In fact, the family lived in her grandmother’s house. Kim Dae Sil’s maternal grandmother had a strong impact on her life, starting with her birth. When Kim Dae Sil was born, she was the fifth child and the first daughter of a well-to-do North Korean family. Her grandmother promised the new born that she would help her get through life, no matter how difficult it might become under a stigma of being born in the year of tiger, not to mention her face, that was not up to the standard of her family.

Indeed, Kim Dae Sil’s life in South Korea was often difficult, but not because of her birthday. In the winter of 1945, Kim Dae Sil’s family moved south across the 38th parallel seeking democracy.[7] The Korean peninsula achieved independence in August 1945 after Japan surrendered, but it also divided the nation in two, with the North aligning with the Soviet Union, and South with the United States.[8] Shortly thereafter, the Korean War erupted, and at eleven years old, Kim Dae Sil was subjected to the turmoil and destruction of battle. When she was twelve, Kim Dae Sil was given an important task. She had to travel alone to meet her father in Busan, and bring back money to her mother in Masan. Her father met her at the train station and entrusted her with an envelope of money. While returning to Masan, a middle-aged woman sat next to Kim Dae Sil and started a conversation with her. Eventually, Kim Dae Sil dozed off, but when she was awoke, she checked the bag she was still clutching and found the white envelope was gone. Her face turned pale as she started to worry about how her family would survive without money for a month. Despite the panic, Kim figured out that the woman, who was sitting next to her, was the only person who could have snatched the white envelope:

No matter what, I couldn’t let her out of my sight. I had to keep her near me at all times until I could talk to police officers. When I got off the train, I held onto her tight, as if my life depended on my grip. We walked together looking for the police. On our way, while I was looking away a bit, spotting two police officers walking toward us, I saw her dropping my father’s envelope, which fell by my right foot. I stooped down to pick it up. When I stood up, the two policemen passed by me and the woman was gone. I opened the envelope and found the money.[9]

In 1953, after the Korean War, Kim Dae Sil’s family returned to Seoul. The family crowded together in a single room in the lower-middle-class neighborhood, Wang Sib Ri, because the war had made things financially tight. Kim remembers that room not only because of the lack of money and space, but because her beloved maternal grandmother passed away there after a long illness.[10]

Despite the financial obstacles, Kim Dae Sil continued her education at Ewha Girls’ High School. Upon her graduation Jeong Chae-sik, who was the English and Bible teacher there, and who later became the Walter G. Muelder Professor of Social Ethics at the Boston University School of Theology (1990-2011), encouraged Kim to attend the Methodist Theological Seminary.[11] She graduated with a Master’s of Theological Studies in 1960, and thereafter was invited to teach at Ewha.[12] While teaching at Ewha, Kim Dae Sil met Dr. Walter G. Muelder, the Dean of the Boston University School of Theology, as well as his wife Martha, and their daughter Linda.[13] Pak Daeseon, who was an alumnus of Boston University School of Theology (Th.D., 1955) and who later became president of Yonsei University (1964-1975)[14], introduced Kim Dae Sil to the Muelder family. She helped them with translation while they were in Korea. In 1962, when Kim moved to Boston for graduate study, the Muelder family met her at Logan Airport. Thus, she started her life in America as a foreign student, joining others in the Korean diaspora.

- The Life of Diaspora: Donald D. Gibson as her home

Kim Dae Sil earned her Ph.D. from the Graduate School at Boston University. She wrote her dissertation on The Doctrine of Man in Irenaeus of Lyon, with Angelos Phillips as her adviosor. She expressed some regret about her dissertation, believing her inadequate knowledge of Greek and Latin, plus insufficient knowledge of the multiple worldviews of the ancient world stood in the way of producing the best possible dissertation. Muelder, who was her mentor in a broad sense of the word, gave some thoughtful advice to her while she was struggling with her dissertation. A Ph.D. dissertation, he reminded her, is only an entrance to the scholarly world; it is not a stage to create a masterpiece.[15] Nonetheless, she worked very hard at the university, claiming, “I didn’t live, I studied.” She remembers, “Going to classes, reading at the library between classes, and eating my two hard-boiled eggs and carrot sticks for lunch.”[16] Being a Korean woman studying in the United States meant she had to manage many expectations from her family. It also required her to navigate cultural differences and different social relationships in the foreign land.[17] A diaspora is a specific form of culture, and a diasporic culture contains or transmits its own memories, tastes, and habits. If one migrates from one place to another, a person senses that he or she must either cross a wide cultural gap or cling to one’s native culture.[18] The theoretician Homi Bhabha, however, has suggested that people in diaspora live in a third or hybrid place, where two or more cultures are mixed. The place is dynamic, with unfamiliar human relationships, different cultural habits, and diverse political thoughts.

One example of how Kim Dae Sil lived in that third space comes from her Mount Holyoke teaching days. When she went there in 1969 many students were involved in anti-Vietnam war protests, and discussed the issues in dormitories night after night. They wanted faculty approval to skip class, so they could participate in the protest without suffering any academic repercussions. One day, they came to Kim Dae Sil and asked her opinion. She answered them:

You should know that I come from Korea where students put their lives on the line when they protest. Two years prior to my departure in 1962 for America for my graduate studies in Boston, there was a protest movement that is generally known as the April 19 Revolution. Spearheaded by students and labor groups, that revolution overthrew the first American-backed president of South Korea, Yi Seungman, and his government. I can still feel the blood spilled by the students. If you are so worried about what will happen to your grades, I suggest that you go back to class and study, and not worry about protests.[19]

In her memoirs she added, “After that night, they never again asked what I thought. They were more than content to let me remain an inscrutable Asian woman.” The cultural gap, widened by different experiences and perceptions, was not easy to resolve in her diasporic life.

Meeting Donald D. Gibson almost a decade later helped Kim Dae Sil to begin to feel at home. The two met at a federal agency, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), in 1978.[20] The encounter not only altered Kim’s life, but Gibson’s as well. Earlier in his life, Gibson had a chance to take a teaching job at a military base in South Korea, but he had rejected the proposal based on his preconceived image of Korea:

My impression of Korea was based on a series of black-and-white images from television footage of the Korean War-bleak, dismal, and dark. I am sure that sense of Korea I had in the 1970s was not far off from the facts. But, Kim Dae Sil transformed them into a rainbow of colors and heavenly feelings.[21]

Although Gibson and Kim were born and raised in distant places, their life journeys had some similarities that prepared them for their common work for social justice. Gibson was born as a farm boy of Iowa in 1938, the same year Kim was born. His father, Donald L. Gibson, was a tenant farmer in the town of Tennant, which had only ninety-five inhabitants.[22] His mother was a faithful Methodist, and wanted Donald to become a pastor. He matriculated at Simpson College in 1956. At that time, he had an idea of becoming a Methodist minister, already having had the experience of preaching in three different churches with a lay preacher’s license. His education at Simpson College, however, led him to walk in a different direction.[23] A course on the Thought and Culture of the Far East led Gibson to have an interest in politics. Looking at another society also raised questions about his own. He began to learn about the history of Native Americans and African Americans, and he realized that racial discrimination created social and economic disparities in American society. At the same time, he started to have doubts about the Christian faith. [24] He stated, “College literally opened my eyes and was in a very real sense the beginning of my life, or at least my life as a thinking, sentient, and sensitized human being.”[25] After graduation, he taught at two high schools in 1961-62, and focused more on the concepts of social-economic justice, just society, and democratic processes.

Having political interests, Gibson worked as a campaign organizer for Warren County Democratic party. He also engaged in the civil rights movement, inspired by the efforts of W.E.B. DuBois, Frederick Douglass, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King Jr. He even traveled to Mississippi to support black voters.[26] When he entered the University of Iowa as a PhD student in history, he joined protests against the Vietnam War. In the years that followed, he worked as a campaign coordinator for the presidential race of Eugene McCarthy in Iowa, and joined the Senate campaign of Harold Hughes.[27] He taught at Simpson College in 1968, before going to Germany to research why German people voted for Hitler.[28] In Germany, he also tasted life in the diaspora. Although he could communicate with scholars, had opportunities to learn new insights, and enjoy the culture of a foreign land, Gibson felt extreme loneliness. After three years of hard work, he left Germany upon completing his research. He returned to America, where his scholarly work, political passion, and experiences led him to start at the NEH in 1978.

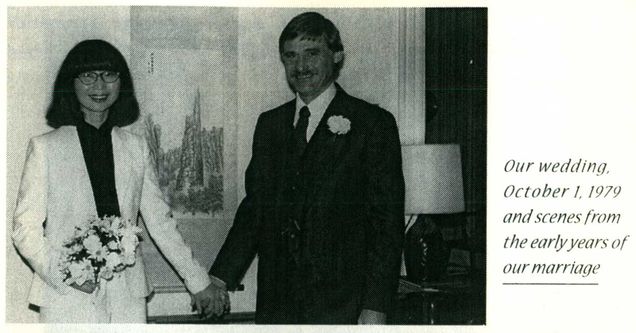

Kim Dae Sil also joined the NEH in 1978, but worked in a different department on media programs. But the two were drawn to each other, and they married in the house of Walter G. Muelder, the Dean of the Boston University School of Theology, in 1979. It was a small wedding, with Martha, Walter Muelder’s wife, playing the piano, and Dean Muelder conducting the ceremony in front of the fireplace in the living room.[29]

After that, two people who had similar journeys from different places, to walk the road of life together. Kim Dae Sil found her home with Donald D. Gibson:

Ever since I had crossed the 38th parallel on foot, holding my grandmother’s hand, fleeing from our hometown in the winter of 1945, I was adrift and lost in this world. Now I had found a home in Don. An Iowa farm boy with hazel-green eyes was to be my heart’s anchor for the remaining days of my life. What we could not know then, but soon found out, was that our “relationship” was the way we’d learn more about ourselves.[30]

Her comment suggests one resolution for life in the diaspora. Home was not defined as a place, but rather in the person she loved. She said that her “shoulder friendship” with Don transformed the wilderness into a home. Home was not the United States, but Donald Gibson who lived in the United States.

After they were married Gibson continued to work at the NEH until his retirement in 1997. He served as the Deputy Director for the Division of State Programs, a Director for Public Programs, as well as Interim Chair. Kim-Gibson Dae Sil left the NEH to become the Director of Media Programs of the New York State Council in 1985, and then began doing freelance work in 1988.[31]

- Filmmaking as the Work of Social Justice: ‘Voices of the Voiceless’

Kim-Gibson Dae Sil has been a Korean-American documentary filmmaker committed to humanizing the voiceless in society since the 1990s. A religion scholar who pursued the question of theodicy, turned into a documentary filmmaker to address her concerns for social justice. “Why did God keep silent amidst the atrocity of the Korean War?” No one could answer her question, and she suspected there was no rational answer. So instead of being engaged in abstract questions and answers, she turned into a filmmaker who tried to give voice to the voiceless.[32]

America Becoming (1991), Sa-I-Gu (1993), A Forgotten People: The Sakhalin Koreans (1995), Wet Sand: Voices from L.A. (2004), Silence Broken: Korean Comfort Women (2004), and Motherland: Cuba, Korea, USA (2006) have been her outstanding films. She has just completed her most recent film, North Korea: People are the Sky (2015). This film has documented In-min, which is called as ordinary people in North Korea. Although each film focuses on different groups of people, she has a specific purpose in making all her films. She attempts to give a voice to the voiceless, focusing on the forgotten, oppressed, and neglected people who face urgent issues.[33]

Her first film, America Becoming, exposed the disparity between the American dream and the lives of newly arrived immigrants; it also addressed their struggles to adapt to a new culture that is divided by racism and social stratification.[34] Sa-I-Gu and Wet Sand dealt with the Los Angeles riots of 1992. They highlighted the racial tensions at work beyond the traditional white-black conflict so familiar to the American public. In particular, she attempted to bring out the way Koreans suffered in the riots.[35] A Forgotten People tells the story of the Koreans who were forced by the Japanese to work on the island of Sakhalin, an island just north of Japan, and then how they were abandoned to serve the Soviet Union at the end of World War II. These Koreans could not go home; they were another nation’s cheap labor.[36] The Rockefeller Fellowship, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and the MacArthur Foundation have funded the films of Dae Sil Kim-Gibson, and she has received many awards, including the Asian American Media Arts Award, the Kodak Filmmaker Award, and CINE Golden Eagle.[37]

Silence Broken was broadcast nationally on PBS (the Public Broadcasting Service) in May 2000. The mainstream press, such as the Wall Street Journal, Entertainment Weekly, and National Prominence acclaimed the film as the most distinguished work of Kim-Gibson’s career. The documentary received the Steve Tatsukawa Memorial Fund award at the 30th Anniversary celebration of Visual Communication.[38] The film emerged out of a series of interviews Kim-Gibson had conducted with comfort women (sex slaves) for the book Silence Broken (1999). Later, she decided to make a documentary film for the historical record—a visual message for the next generation. Kim-Gibson Dae Sil used the testimony of comfort women as the primary source of the film.[39] A testimony of Hwang Keum Ju, who was a comfort woman, motivated Kim-Gibson to make this film. When Kim-Gibson translated her testimony into English at a conference in Washington D.C., Kim-Gibson shocked by her stories. After the translation of Hwang Keum Ju, Kim-Gibson Dae Sil said, “Twelve-year-old-girls were drafted to become comfort women. If I had been six or 10 years older, I could have been one of those women” in an interview. [40] Indeed, the Japanese government recruited Korean Women with lies and threats during the Second World War. The Japanese military forced them to have sexual intercourse with soldiers, and if they resisted many of them were killed by torture.[41] After the war, the Western allies created war tribunals in which thirteen Japanese soldiers were punished in a case where Dutch women were used for sexual services, but cases that involved women from Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Indonesia were ignored.[42] Kim-Gibson Dae Sil attempted to hear the silenced comfort women, and to give them the opportunity to speak. Her film rarely used narration, because the authentic voices of the victimized and the oppressed carried the story.

In Motherland, Kim-Gibson showed two sisters, who live in two different worlds. Martha lives in Havana, Cuba; her sister Camilla lives in Miami, Florida. Kim-Gibson uses the film to explore the meaning of a homeland. In recent, she made a film about North Korea, in part because many people in the United States have negative preconceived ideas about the country. Most Americans demonize the three dictators: Kim Il Sung, Kim Jung Il, and Kim Jung Un, and they imagine the citizens of North Korea as nothing more than puppets.[43] Thus, Kim-Gibson Dae Sil tried to show the ordinary people in North Korea, and made the subtitle of the film, People are the Sky. To make this film, she interviewed many people including the well-known novelist, Hwang Seok-yeong and citizens of North Korea, in their homes and on the streets. All her films aim to depict minorities and the victims of society as human beings, portraying them as real people and not just issues or numbers.[44] She has always sided with the powerless and the minority in the stories she tells, and seeks to inspire other people to take risks and give voice to the voiceless.[45]

In July 2015, Kim-Gibson Dae Sil will be 77. She is still living in the diaspora, making her home in America, the land of her husband’s birth and her adopted country. She does not stop her work at the margins of society, and those on the edge of the diaspora. She ended the interview with me, saying “The life is always more than what you think, what you know, what you believe in. There is more. Look beyond. Life is not all about you. Life is all beyond you. Look beyond you. If you don’t know what that is, don’t get discouraged. Just look for it. Sometimes you will find it, other times it will find you.”[46]

Kim-Gibson Dae Sil talked about the interrelationship between her Ph. D degree at BU and the filmmaking work.

Her saying for the next generation, including the interviewer.

Written by Heuiseung Lee

Edited by Daryl Ireland

[1] Kyoung Bae Min, A History of Christian Churches in Korea (Seoul: Yonsei University Press, 2005), 178-182.

[3] Hyaeweol Choi, Gender and Mission Encounters in Korea: New Women, Old Ways (Los Angeles: Global, Area, and International Archive University of California Press, 2009), 145.

[4] Kim Gu (or Kim Ku) is a historic figure in Korea. He was active independent activists and largely contributed to the establishment of “The Korean Provisional Government” in Shanghai. Under the Japanese ruling, many Korean moved to Shanghai and established the KPG for continuing the independence movement. Many Christians were also involved in the KPG, and Gu was one of head committee members there. Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regims 1945-1947 Volume 1., (Seoul: Yuksabipyungsa Press, 2002), 180. After independence from Japan, Kim Gu raised strong opposition against the establishments of government in both South and North Korea because he wanted to have one united Korea. He was assassinated by An Du hee in June 26, 1949. Kim Shin, Chokukeui Hanuleul Nalda (Flying the sky of the motherland), (Seoul: Dolbege Press, 2013), 127-28.

movements. Many Christians was also involved in the Gu was one of head committee members.

[5] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Interview with the author, January 3, 2015; Mahn-yol Yi, “The Birth of the National Spirit of the Christians” in Korea and Christianity, Chai-Shin Yu, ed., (Seoul, Berkeley and Toronto: Korean Scholar Press, 1996), 41-45

[6] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Interview with author, January 3, 2015.

[7] http://iamkoreanamerican.com/2011/03/14/dai-sil-kim-gibson/

[8] Bruce Cummings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2005), 186-87.

[9] Donald D. Gibson, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, ed., Iowa Sky: A Memoir (New York: Shoulder Friends Press, 2013), 56.

[10] Donald D. Gibson, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, ed., Iowa Sky: A Memoir (New York: Shoulder Friends Press, 2013), 81.

[11] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, conversation with author, January 3, 2015. See also the interview with Chai-sik Chung at the Center for Global Christianity & Mission, https://sites.bu.edu/koreandiaspora/files/2014/09/KOREAN-DIASPORA-INTERVIEW-SCRIPT-REVIEWED-BY-DR-CHUNG.pdf

[12] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, conversation with the author, January 3, 2015.

[13] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Email message to the author, March 16, 2015.

[14] https://sites.bu.edu/koreandiaspora/individuals/boston-in-1950s/daesun-park/

[15] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Email message to the author, March 16, 2015.

[16] Donald D. Gibson, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, ed., Iowa Sky: A Memoir (New York: Shoulder Friends Press, 2013), 117.

[17] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Interview with the author, January 3, 2015.

[18] Paul Christopher Johnson, Diaspora Conversions: Black Carib Religion and the Recovery of Africa (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006), 35.

[19] Donald D. Gibson, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, ed., Iowa Sky, 127.

[21] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Looking For Don, 58.

[22] Donald D. Gibson, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, ed., Iowa Sky, 47.

[24] Gibson remembered the letter from Walter G. Muelder in 1957 when he was a pre-ministry student. Muelder wanted Gibson to consider BUSTH for his divinity school in the future. However, Gibson explained why he was not going to Seminary in the reply. Muelder wrote back a letter to him because he thought Gibson was “a victim of fundamental Christianity.” Donald D. Gibson, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, ed., Iowa Sky, 94.

[25] Donald D. Gibson, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, ed., Iowa Sky, 100.

[29] Donald D. Gibson, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, ed., Iowa Sky, 31.

[31] Donald D. Gibson, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, ed., Iowa Sky, 270-71.

[32] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Email message to the author, March 16, 2015.

[33] Megan Ratner, “Dreamland and Disillusion: Interview with Dai Sil Kim-Gibson”, Film Quarterly Vol. 65 (1) (Fall 2011): 34. Accessed by March 12, 2015 14:18

[34] Frances Gateward, “Breaking the Silence: An interview with Dai Sil Kim-Gibson”, Quarterly Review of Film and Video (published online: June 2010): 100. Accessed by March 12, 2015 at 11:23.

[35] Ju Yon Kim and Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, “Remembering SA-I-GU,” What is Africa to me now? No.113 (2014): 147-148. Accessed by March 3, 2015 14:25.

[36] Megan Ratner, “Dreamland and Disillusion”: 34.

[37] Frances Gateward, “Breaking the Silence”: 100.

[38] The article of Korea Times, Los Angeles, November 30, 2000.

[39] Frances Gateward, “Breaking the Silence”: 106.

[40] Comfort Women break silence: An Interview with Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, The Asian Reporter (Sep 1999).

[41] Hyung Yang, “Revisiting the Issue of Korean Comfort Women: The Question of Truth and Positionality,” in The Comfort Women: Colonialism, War, and Sex, Chungmoo Choi, ed., (North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1997), 51.

[42] Chungmoo Choi, ed., The Comfort Women, vi.

[43] Megan Ratner, “Dreamland and Disillusion”: 38.

[44] Ju Yon Kim and Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, “What is Africa to me now?” 145

[45] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Email message to the author, March 16, 2015.

[46] Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Interview with the author, January 3, 2015.