Yang Yuchan: The Mouthpiece of Korea and Defender of Liberation

Born in Busan in 1897, Yang immigrated to America at an early age and graduated from McKinley High school in Hawaii in 1916. His connection to Boston started when he transferred from University of Hawaii to Boston University during college. He obtained his Bachelor of Science and Doctor of Medicine at Boston University in 1923, and opened a private practice in Hawaii. He was a successful physician and a brilliant leader— while working as a mentor to other physicians and managing his own hospital, he founded the Korean University Club (KUC) and directed the Honolulu YMCA and Honolulu Korean Christian Association. He played a pivotal role in bridging the Western and Korean culture and providing a spiritual and cultural unity for the Korean community in Hawaii.

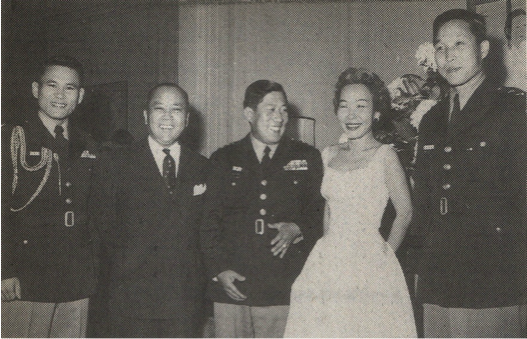

His official political career started when the Hawaiian consul general Kim Yongsik recommended Yang to visit President Rhee Syngman (Yi Seung Man) in Busan in 1951. Yang was already actively involved in political and social activities alongside his medical career, and he had been mentored by President Yi during his college years—President Rhee was in the process of completing his Masters degree when he first encountered Yang as an undergraduate student. President Rhee asked Yang to become an ambassador to the United States, saying “Your time has come. You must serve and help the thirty million Koreans who are dying from poverty and war.”[1] After much hesitation and thought, Yang decided to take the position and was officially appointed an ambassador on April, 1951. While his passion for medicine still remained strong and fervent, he perceived it necessary to commit his life for the good of the nation. The following year, he became the Korean representative to the United Nations and worked for the advancement of war-torn Korea during and after the Korean War.[2]

He was the public voice who spoke against the competing powers of the United States and the Soviet Union in the aftermath of the Korean War. He was extremely unsettled by the division of South and North Korea, and in 1953, he declared that the Korean army will leave the United Nations military headquarters if Korea were to be remained split.[3] Moreover, in 1959, he attempted to bring the truth to light when he announced that the supposed news of a South Korean battleship attacking a Soviet survey ship was falsified. He contended that the false news report was an attempt by the Soviets to vilify the Korean navy and thereby taint the international reputation of South Korea.[4] In 1960, he worked as both an ambassador to the United States and Brazil, and from 1965 to 1972, he travelled around the world as a roving ambassador. He was also a prolific writer and a charismatic public speaker. He wrote Our Common Task (1953), The Aspirations of Korea (1954), and Korea Against Communism (1966). To his dying day in 1975, he actively fought against Communism and acted as a mouthpiece for Korea.

For Yang, Christianity was an important impetus for his sociopolitical activities. As one of the founders of the Boston chapter of the League of Friends of Korea, Yang, along with ninety other members, advocated independence of Korea against Japanese occupation precisely because of his calling as an ambassador for Christ. For him, independence of Korea was not just a political issue but a moral cause based on human equality and solidarity. He spoke on many occasions at Boston University and Harvard concerning Korean independence.[5] Further information regarding his involvement with the Korean independence movement in Boston can be found here. In his radio broadcasting speech, he specifically stated that his identity as a Christian compelled him to fight against Communism and any oppressive form of government:

“Yet we can turn to our Creator for solace at all times, and that seems to me, as a citizen of a land whose people have suffered the agonies of modern warfare and Communist aggression, the great difference between my creed and the creed of the enemy of all mankind. For we who believe in God are confronted by an ideology which denies His very existence, ridicules the spiritual soul of man, insists on worship of only the all-powerful state, and has as its sole aim the conquest and enslavement of all those who differ with it.”[6]

As with any historical figures, Yang remains to this day a controversial figure. He could not escape criticisms for his extremely passionate rhetorics, and some nationalists blamed him for not being able to reclaim Dok-do island which was lost during the Russian-Japanese War (February 8, 1904-September 5, 1905). However, his copious accomplishments as an ambassador and a defender of liberation and independence is undeniable.

Citations

[1] Kyeonghyang Newspaper, June 30, 1972.

[2] Kyeonghynag Newspaper, August 8, 1962.

[3] Kang Junman, Journey Through Korean Modern History (Seoul: Heroes and Ideology, 2004), 26.

[4] Donga Newspaper, January 1, 1960.

[5] https://sites.bu.edu/koreandiaspora/issues/the-korean-independence-movement-and-boston-university/

[6] Yang Yuchan, “This I Believe.” http://thisibelieve.org/essay/17119/

Written by: Soojin Chung