Student Work Wednesday- Featuring Celeste Femia

This week we’re highlighting the work of Gastronomy student Celeste Femia. Celeste completed a project in which she recreated a historical recipe for the Cookbooks and History course taught by Karen Metheny here at Boston University’s Metropolitan College.

Recreating a 19th Century Orange Fritter

In my search to find a historical recipe for recreation, I stumbled upon a gem from the late 19th century, “Miss Corson’s Practical American Cookery and Household Management” by Juliet Corson. Juliet Corson, an instructor, and superintendent at the New York Cooking School, collaborated with the Commissioner of Education to create this cookbook that went beyond regional boundaries. Published in 1885, this cookbook is a compilation of recipes contributed by locals from the Western and Southern regions of the United States.

Its diverse range of contributions piqued my interest, and I began combing through the recipes until one in particular, “Orange Fritters,” caught my eye. The idea of slicing, battering, and deep-frying oranges was completely unfamiliar to me. I had never tasted an orange fritter before, so naturally, my curiosity got the better of me, and I was eager to discover both the visual appeal and flavor profile of this concoction.

Before diving straight into the recipe, I wanted to explore the origins of the fritter. A bit of online sleuthing unveiled that these delightful fried treats likely made their debut during the Roman Empire. In Italy, they are named not after their ingredients, but rather after the frying cooking method, known as “fritte.” Additionally, early Italian cookbooks from the Middle Ages shed light on the distinctions between fritters fried in oil, ideal for religious days when animal products were forbidden, and those fried in lard, more suitable for everyday fare.

The world of fritters is a mixed bag of flavors and textures. Savory options, from fritto misto featuring meat, seafood, and vegetables dipped in batter and crisped up in olive oil, to the aromatic Indian pakora. In Japan, the batter-frying technique, introduced by the Portuguese and Spanish in the late 16th century, gave rise to tempura, which has become an integral part of Japanese cuisine. Sweet variations of fritters, including the French beignet and its counterparts, have also found their way across the globe.

To recreate the historical orange fritter recipe, I first needed to gather the ingredients: flour, an egg, salt, olive oil, water, oranges, powdered sugar, and oil for frying. Fortunately, these ingredients are readily available in today’s markets, and I was pleased to find that most were already stocked in my cupboards.

The cooking process began with careful preparation. I assembled the ingredients and began crafting the batter. Following the instructions, I noted the need to beat the egg white into a stiff froth. Channeling the spirit of traditional methods, I separated the yolk from the egg white and began vigorously whisking. After about 10 minutes of continuous, wrist-burning effort, my egg whites achieved their desired stiffness.

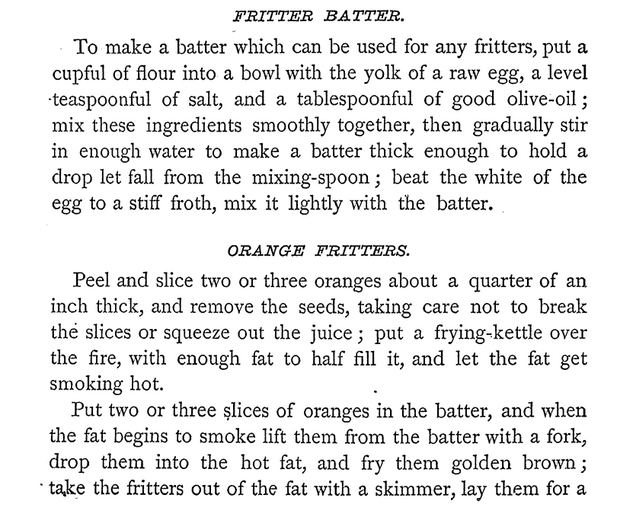

In another bowl, I mixed one cup of flour, a teaspoon of salt, and a tablespoon of olive oil. The next step called for “enough water to make a batter thick enough to hold a drop let fall from the mixing spoon.” Interpreting this as something like a pancake batter, I measured approximately one cup of water, incorporating it gradually while mixing. To assess consistency, intermittent checks were conducted to evaluate how well the batter adhered to a spoon. It took the entire cup of water to achieve what appeared to be the correct texture. Finally, I folded in my stiff egg whites.

With the batter ready, I turned my attention to heating the oil. The recipe called for using a “frying-kettle over the fire, with enough fat to half fill it and let the fat get smoking hot.” I opted for a deep stainless-steel saucepan with canola oil due to its smaller diameter but greater depth, ideal for frying in small batches. The recipe’s instruction to heat the fat until it is “smoking hot” terrified me! The thought of submerging a batter-coated, liquid-filled fruit into sizzling oil seemed like a potential recipe for disaster, with either scalding oil splatters on my arms or quickly burnt fritters. So, I opted for a temperature more in line with what I might use for frying chicken. To ease into it, I conducted a test round with one orange slice.

My initial attempt revealed some errors: first, some of the batter got left behind on the fork, leaving a section of the orange without any coating, resulting in a hollow space where the orange juice seeped out. Additionally, the oil was not hot enough. Learning from this, I increased the heat and made sure to subsequently stab the orange with a fork, thoroughly coating the slice in batter, and then immersing it into the hot oil. This method proved much more effective; all sides of the orange were evenly coated, and the slices were frying up beautifully. Working in small batches of two at a time, I battered and fried the rest of my slices. Each orange slice was laid on paper towels to drain and then dusted with a generous layer of powdered sugar.

So, how did they taste? I will be honest, my orange was not the sweetest, and in hindsight, I wish I had sampled a slice first to gauge the flavor profile before diving into the frying process. A hint of bitterness lingered, likely a result of my less-than-sweet orange combined with the olive oil in the batter. Given that the batter itself lacked sugar, the fritter’s sweetness relied heavily on the powdered sugar on top. Despite this, they turned out surprisingly good.

Reflecting on this experience, if I were to recreate these orange fritters again, I’d consider adding sugar, testing the orange beforehand to ensure optimal sweetness, and I would use lard for frying, as it might enhance the overall flavor profile and possibly result in a more delicious fritter.

References:

Corson, Juliet. 1885. Miss Corson’s Practical American Cookery and Household Management.

New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company. https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa/58.

Encyclopedia Britannica. 2021. Fritter. Date of access, November 15, 2023.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/fritter.

Montanari, Massimo. 2012. Let the Meatballs Rest: And Other Stories About Food and Culture.

Columbia University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bu/detail.action?docID=1028072.

Rachman, Anne-Marie. 2023. Corson, Juliet, 1842-1897. MSU Libraries Digital Repository.

Date of access, October 20, 2023. https://d.lib.msu.edu/msul:63.