Home

Trauma Theater: Real Therapy or Fun Fiction…

Before I begin explaining my understanding of Trauma Theater, I must first begin with a little history on how I learned of trauma theater. I recently learned of a trauma-based therapy that utilized theater as a means of coping with trauma. In the book, “The Body Keeps the Score” (van der Kolk, 2014) Dr. Van Der Kolk discusses his positive experiences with theater-based trauma therapy and even discusses how it helped his son following a mysterious illness.

There is little information about exactly when this form of therapy started or who pioneered it, but one thing I found to be certain was that this therapy method is alive and well. It seems to be consistently used with troubled adolescents and veterans suffering from PTSD but can also be applied to others suffering from a traumatic incident. Historically speaking it may date as far back as Shakespeare and his utilization of trauma to create while writing his plays. Dr. Van Der Kolk discusses in his book that he learned about it from a group of veterans he had been treating for PTSD and how he discovered that the theatrical production was a part of the recent positive changes he observed during therapy with these veterans.

Dr. Van Der Kolk’s book is what first introduced me to this type of therapy and although I found it to be an interesting process, I did notice that a majority of the programs discussed in the book or on the internet reside on the east coast of the U.S. I have no doubt some also exist on the west coast, but since I have mostly lived in Colorado I had never heard of this therapy. Naturally, I was a little skeptical of the process and had difficulty seeing how it would apply to me or anyone I know who has experienced trauma.

In my profession I work a lot with juveniles who have entered the justice system or are frequently contacted by the police. We do not have programs like you see in Boston or New York City. In Colorado the typical approach is what you see in mainstream psychology. There are programs that work with juveniles, but it is more traditional counseling and if they have absent or uninvolved parents it typically does little good because they immediately return to crime and drugs.

This is why I found the “Trauma Drama” program so interesting. In an article I found on Statnews.com, “Trauma Drama is a theater-based therapy program for teenagers with severe emotional and behavioral problems. The idea is that theater can help this group of troubled adolescents regulate their emotions and build skills to cope with trauma” (says, 2016). After reading about these programs, I kept wondering if there was an application in the juvenile justice system as a whole.

Besides its use among troubled adolescents, I found an article in Psychology Today that discussed the work of Renee Emunah and how she was using her “techniques, exercises and methods to bring new life to hospitalized patients experiencing psychosis” (Healing Trauma with Psychodrama, 2018). I am not a psychologist, but to me this sounds like something worth considering just given the evidence of success with veterans, adolescents and people experiencing varying degrees of trauma. So why isn’t this method nationally recognized and used? Even in Van Der Kolk’s book it states “all of these programs share a common foundation of the painful realities of life and symbolic transformation through communal action. Love and hate, aggression and surrender, loyalty and betrayal are the stuff of theater and the stuff of trauma” (van der Kolk, 2014).

I will not argue that theater draws on the same emotions that are often experienced during trauma. The human experience is full of difficult and often painful encounters, so why is this not a more commonly known and utilized therapy? Is it simply because it can only act as a piece of the solution to dealing with trauma or is it because mainstream psychologists stick to what they’ve learned and use what has worked best for them? From my research this seems to be a widely used technique, but there is little information on why or if this form of therapy really works for people.

Do psychologists always have to have the data present to accept a certain method for treating patients? I am not sure if there will ever be a definitive answer until more in-depth research is completed on the success of such a program, but if that were always the case then why are therapies like EMDR so widely used? There are plenty of people on both sides of the fence when it comes to EMDR, yet it is commonly used in trauma-based therapy. I guess as an individual I would have to decide for myself. Maybe a program like this could be introduced in Colorado and could be utilized to aide adolescents in leading meaningful lives or could help veterans process their trauma. Maybe a program like this could even be introduced with first responders who are suffering from PTSD.

Ultimately, there will probably always be those who find drama therapy useful and can see the success while others will undoubtedly find the issues within. Just like many other forms of therapy they do not all work for everyone. We all have certain things that resonate with us better than others or our brains are wired differently which means different approaches are necessary to live successful and meaningful lives. I can not definitively say that trauma theater is fiction and have found that programs exist which utilize drama therapy for treatment. It is not a one stop shop to dealing with trauma, but I can see the benefits it may offer for some people. Trauma theater may allow someone to access their experiences in a safe space, by giving them the opportunity to confront an abusive parent or the offender who assaulted them. There are so many options for therapy out there it is hard to dismiss something with such a large following.

Maybe trauma therapy is here to stay, and we will see more studies done showing the progress of the programs available. This type of therapy seems to be utilized on such a broad spectrum of trauma survivors that there is no reason it shouldn’t continue to be used.

References:

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

says, M. B. (2016, August 23). Teens work through trauma using theater as therapy. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2016/08/23/theater-trauma-teenagers/#:~:text=Called%20Trauma%20Drama%2C%20it

Healing Trauma with Psychodrama. (2018). Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-new-normal/201804/healing-trauma-psychodrama

(image) Young People Are Using Musical Theater to Heal Their Trauma — and It’s Working. (2019, July 12). NationSwell. https://nationswell.com/news/young-people-musical-theater-trauma/

Trauma on the Job: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Law Enforcement Officers

As we have learned throughout this course, PTSD is prevalent among many people and professions. However, being a law enforcement officer, PTSD is a personal concern because every police officer is one situation or call away from experiencing something stressful and traumatizing that could end up causing them to suffer from PTSD. PTSD can commonly be linked to the inability to sleep, nightmares, intrusive memories that don’t fade in intensity, physical reactions to places or other things associated with the event, the feeling of always being on guard or, by contrast, feeling numb (Lexipol, 2016). Karen Lansing, a licensed psychotherapist and Diplomate of the American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress, states “it’s tempting to associate PTSD with a single incident, stressing that it is often caused by exposure to numerous traumatic incidents over several years or, in some cases, an entire career. I typically see what we call cumulative PTSD” (Lexipol, 2016). Additionally, Lansing states “Incidents involving shootings or improvised explosive devices will often open the door. It’s easier for an officer to come in after one of those incidents because everyone understands that they should be talking about it. But the shooting or ‘things that go bang’ are just the latest incident sitting on top of a stack of other traumatic incidents” (Lexipol, 2016).

Dealing with PTSD in law enforcement provides its own challenges and obstacles, but other challenges these officers face are what treatments are available and effective to help law enforcement officers deal with PTSD. Lansing uses a technique called Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), where Lansing acts almost like a Field Training Officer, guiding the officer through a process of reliving the incident, resolving the trauma, and then mining it for any learning points it has to offer that could be important in the future. EMDR allows the brain to reprocess the incident to full resolution in a safe environment. “The officer is in full control, with me riding shotgun should he need some back-up if things get hung up” (Lexipol, 2016). Lansing says she begins the process of EMDR by tending to the most highly triggering event first such as an officer involved shooting. She states that once this memory is neutralized or the officer is at peace with it, she then moves on to what flashback comes next. Lansing continues to knock these memories off one by one until the officer is feeling better.

As important as these therapy sessions are to officers suffering with PTSD, I have argued and as this course has proved, leadership and administration of police departments are just as critical and important in helping officers deal with PTSD. Lansing states that she can take care neutralizing PTSD easily through therapy sessions, however if she encounters trauma after she neutralizes the event due to poor leadership, she might not be able to succeed and help the officer. “In all of the many hundreds she has helped return fully to the job after treating their PTSD, there are nine who Lansing was not able to return, six in one law enforcement agency and three in another. These were very troubled agencies and all nine were lost due to this leadership issue” (Lexipol, 2016) In order to overcome the obstacles of poor leadership, Lansing believes “training first responders as well as ensuring that officers get at least seven hours of sleep and receive early clinical interventions, such as department-wide annual check-ins with a psychotherapist. Since 2008, she’s also focused on the need for better leadership training” (Lexipol, 2016).

This information and study completed by Lansing has really solidified the need in my opinion for all police departments to start early intervention when an officer is exposed to a traumatic event. My department offers peer counselors to any officer who needs someone to talk to if they are having trouble. The issue with this is that most police officers that I know don’t like to be seen as weak and will never admit that they are suffering or need help. As Lansing states, good leadership and training is needed so that everyone in a department is aware of the effects that PTSD can have on a person. Creating a culture that embraces the impact that PTSD has on its officers starts at the top and trickles down through leadership and training. Being able to understand this so that an officer doesn’t feel the need to suppress their feelings, so they aren’t seen as weak or vulnerable by their peers is imperative to combat PTSD. Overall, PTSD is prevalent in law enforcement and through this course, studies, and my own experience, it is nothing to take lightly and finding ways to help those officers suffering from PTSD is a collaborative effort by everyone in a department.

References:

Lexipol (2016). Trauma on the Job: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Law Enforcement Officers. Retrieved April 21, 2022 from https://www.lexipol.com/resources/blog/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-law-enforcement-officers/

Unpacking Psychopathology

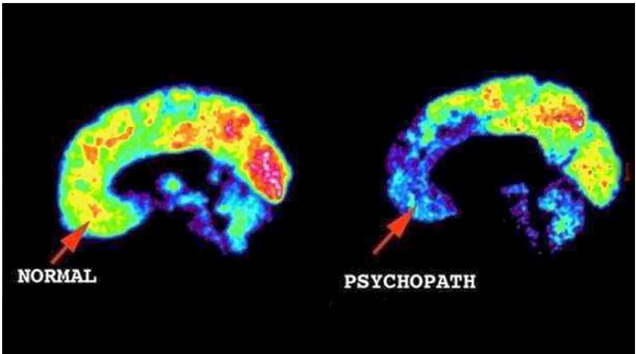

Psychopathy is a disorder that has encapsulated the minds of societies around the world. You may be wondering, what makes psychopathy so interesting? Depending on who you ask you will probably get a different answer. Some people believe that it is because they are able to tap into the egos that a most of us would rather and chose to stay hidden. Looking back at the research done by Sigmund Freud on psychoanalytical theory, he postulated that the mind is composed of three elements. The Id, Ego and Super-Ego. An average person's Ego "ensures that the impulses of the id can be expressed in a manner acceptable in the real world" (Cherry, 2020). What makes psychopathy interesting is that psychopathy is that, the parts of the brain that are responsible for emotions such as empathy, guilt, fear and anxiety are still present but reduced. With advancements in technology we now have the ability to scan people's brains (as seen below in the image by Dr. James Fallon) and take a more introspective glimpse into what the minds of people. A study done the University of Wisconsins School of Medicine shows that "both structural and functional differences in the brains of people diagnosed with psychopath and those two structures in the brain, which are believed to regulate emotion and social behavior, seem to not be communicating as they should" (Koenigs, 2017). This study opens so many doors for researchers from all different disciplines to explore psychopathy. It is important for psychopathy to be explore by numerous disciplines because not only it is important to know the medical side of psychopathy because it allows us to view this disorder from multiple angles. Including different disciplines such as education and psychology into the world of psychopathy allows a more effective and ethical approach to psychopathy. Education is vital because it allows it allows us to learn what causes psychopathy, who may be more susceptible too and knowing these things can be substantial in reducing a problem before a larger one arises.

I think another large part of what makes people so fascinated by psychopathy is that on the outside they are just like anybody else, they have an ability to turn on and off their charm and their cunningness. These characteristics often lead to them being attractive to others and being able to advance in the world. They know how to get what they want, they are smart and know how to manipulate others. The idea of having a so-called "hidden personality" is what makes people so interested in psychopathy. Also, the idea that we may not even know someone is a psychopath, they could be standing right next to us, a friend, a family member or really anybody. This has transcended into them being popular topics in media, film, television, writing and more.

Sources:

Fallon, J. (2005). Control v. james fallon's brain. CNN: UC Irvine. accessed 16 April 2022.

https://www.cnn.com/videos/bestoftv/2014/05/28/erin-intv-fallon-inside-the-mind-of-a-young-killer.cnn

University of Wisconsin-Madison: School of Medicine. (2017). Psychopath's brain show differences in structure and function.

https://www.med.wisc.edu/news-and-events/2011/november/psychopaths-brains-differences-structure-function/#:~:text=The%20study%20showed%20that%20psychopaths,of%20brain%20images%20were%20collected.

Cherry, K. (2020). Freud's id, ego and superego. Very Well Minded.

https://www.verywellmind.com/the-id-ego-and-superego-2795951

Images, Trauma, and Motherhood

Please note: This blog post reflects primarily my opinion about a topic I have wanted to discuss for quite some time. My writing does not reflect the entire picture, nor is it meant to reflect truth for all. Many experiences can look different. I would offer, however, that engaging with my post might offer some insight into a topic that is too often ignored or understudied in the academy today.

As many are painfully aware, trauma is not a one size fits all. It does not come neatly wrapped in something we can understand in its full magnitude. It is, however, a reality for so many people, if not most living in the world. From natural disasters to cycles of abuse in families, it permeates the bodies and experiences of those living in various situations. Though it does not just affect one population in the US, a few populations are more inclined to deal with constant and complex trauma than other groups. To name a few, those in marginalized groups, including women, poor people, people of color, and those with disabilities, are at the top of the list.

Though there are other populations, including veterans, EMTs, and police, as we have discussed in our course, these groups often experience trauma connected to their profession, not simply existing. Though trauma is trauma, the distinction I am making here is that a poor single caregiver is experiencing trauma by living in a society that values wealth and production. In contrast, the enlisted person chose to engage in what they knew could involve dangerous and violent situations. Neither of them deserves trauma by any means, but one is more based on a career path versus how the other is forced to live. I note this because I will be discussing a population experiencing trauma based on the color of their race and gender.

Since the transatlantic slave trade, Black mothers have watched their children be abused, assaulted, and harmed at the hands of predominantly white men. This is not a debatable assertion but rather a fact and reality. I mention this first because to discuss the topic of images, trauma, and motherhood; one must first understand this is not a new issue. However, it has not been centered and will be in the rest of my post. For many who have studied relatable issues, this has looked like trying to understand how these mothers respond to their black sons being abused or killed. This conversation is meaningful and has some research attached, so I will discuss Black mothers' relationships with their daughters.

Black women have to protect their daughters who share their faces, anatomy, and common experiences in a country deeply struggling with white supremacy and sexism. For Black mothers raising black daughters, the images of young women being assaulted, abused and slammed down by men is highly traumatizing. It is the constant reminder that not only do black girls and women have to deal with racism, but their anatomy somehow makes them a target for what folks might refer to as a double whammy.

Black mothers seeing the images of Breona Taylor, Sandra Bland, and the countless faceless women who experience sexual assault remind us that we live in a country that is not only okay with abuse and harm of black women but also causes harm. This is due to structural racism and sexism. They are constantly retraumatized by the images and respond as parents in ways that mirror that trauma, often in parenting styles. We find that Black mothers can be very strict with their daughters (almost to a fault) because they constantly fear losing their children. This can mean telling them to cover of their bodies, forcing them to be more mature than anyone around them, or training them to never be their fully vibrant selves in the face of any authority figures. These teachings take a toll on black young women's light; it dims it and often make them feel less powerful, worthy, and valued. Even as this is not the intent of black mothers, it is the protective response to trauma they do not want to be imposed on their daughters.

I believe that knowledge is power, so having media outlets offer stories about the experiences black women and their daughters are facing is important. However, the images do not help. Instead, it can be traumatizing and creates extreme fear in the bodies of black women, young and old. I am not saying these images should not be shown, but to have no support in place for black women is seemingly by design and further exacerbates the issues. It is an everyday nightmare for a black mother to see images of young women who are being harmed by individuals and systems. I would offer this is not by accident but rather as bold statements that the bodies of black women do not matter.

Harm toward black women should be stopped. It is imperative that as this continues, we must build out specific support tailored for black women. In essence, the issue needs to be studied and researched so models of support can be developed around the country.

My Journey with Art Therapy

With a history of anxiety, addiction, and depression on both sides of my family, my mother believed it was best for our family to start therapy when I was around the age of 7. At that time it was cognitive behavioral therapy. Sometimes I would play with toys and games while talking to my therapist and other times I would just sit on her couch for the whole session. At the age of 9 my father died unexpectedly of a heart attack. At that time my mother moved us to a center specific to families who are experiencing new grief. who have recently lost someone. I was added to a therapy group for children who lost a parent.

That time in my life following my father's death is so clear for me at some points and so hazy at others, which I have learned is my brain protecting me. I brought up the group therapy because we practiced art therapy every week, and I had not even realized that is what my grief therapy group was centered around until I started researching art therapy for this blog post. To the best of my memory the pieces of art I made were:

- a clay object to commemorate my father (I think it was in the shape of a heart...

- A mini flip book containing ten reasons I love my dad. Those are the only two pieces of art I remember vividly.

- A box with pictures I associated with my father on the lid, and important objects I associated with him in the box. I think we made the box to contain all the pieces of art we had made in our time at the center as well.

In researching for and writing this post I am able to realize the power of art therapy. I had been so skeptical of it when we began learning about different therapeutic approaches for people dealing with trauma. But, something clicked in my head and I realized that therapy group was so essential to my grieving process. Focusing on using art to celebrate the parents we had lost gave us the safety and comfort to open up to one another about our feelings and what we were going through emotionally. I think the perfect therapeutic combination for me at that time was art therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. I am so grateful for this class for giving me the tools, materials, and space to realize this truth about my past. It may even inspire me to take up art therapy again.

Yoga and PTSD

Expanding on a previous discussion post I created, regarding one of the alternative approaches, yoga and mindfulness. Learning about the practice of yoga and its beneficial value to individuals mental health and other psychological stressors has intrigued me over the past few years. Growing up, I was taught the importance of movement and mindfulness but had not always fully appreciated its purpose. For example, my parents always turned to physical activity as a way to de-stress. Even my mom can recall from her childhood, as a pre-teen, going for runs throughout her neighborhood as a way to escape her parental/familial stressors. Interestingly enough, my mom carried this healing method into adulthood. She is now is a yoga and pilates teacher and personal trainer. She has used her training to not only benefit those within a vast range of ages and/or capabilities, but also to a unique group. She specialized in a practice of yoga for veterans in order to help treat/alleviate their symptoms of PTSD. As learned throughout this course and from reading The Body Keeps The Score, "ten weeks of yoga practice markedly reduced the PTSD symptoms of patients who had failed to respond to any medication or to any other treatment". It is amazing the power that yoga has on mindfulness, movement, creating a connection to ones own body that once seemed foreign to them, being present and in control, calming of the vagus nerve/amygdala, and much more. My mom, throughout my upbringing, has remarked on the benefits of sleep, deep breathing, mindfulness, and nutrition. She often utilized her breathing techniques when feeling nauseous and has also used it to teach me how to avoid fainting when I would be in claustrophobic environments.

In terms of veterans and PTSD, she aimed to provide support and teach them that their body is a safe place that they can trust because a lot of them may feel violated by their own bodies or closed off as a survival skill. She spoke about how important it was to acknowledge that sometimes they may need to leave the session because the class was too palpable and how important the language you use is. They may feel that their bodies have been violated. She aimed to teach them how to down regulate their nervous systems, connect them back to their senses in a way that does not overwhelm or overload their nervous stems, and more. I think, like my previous self, people hold misconceptions on yoga. They may view it as strictly a way to stretch or as not a proper work-out therefore pose the question as "why even bother?" or view meditation as boring. I think proposing more interventions/awareness around why yoga is so beneficial to ones mental health would help create awareness, a safe space for those struggling, or opportunity for those who were skeptical on its other purposes get a chance to explore it. There is now plenty of science to support the fact that nasal breathing, deep breathing, mindfulness, and movement allows the parasympathetic system to be activated or "re-registered". Mindfulness can help with this too, because "The basic premise of the practice was not only to notice the things that surround you, but also to pay attention, without judgment, to sensations that happen within the body, regardless of how painful they seem. This practice has been shown to help not only with reducing negative thinking and rumination, but also with rebuilding brain structures that are impacted in people who have survived trauma." (Rousseau, 2022) People who are suffering from PTSD need grounding, and yoga is a practice that IS grounding.

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 4: Pathways to Recovery: Understanding Approaches to Trauma Treatment. Trauma and Crisis Intervention. MET CJ 720 02. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Van der Kolk: The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (Reprint ed.). Cloud reader - read.amazon.com. (n.d.). https://read.amazon.com/reader?asin=B00G3L1C2K&ref_=dbs_t_r_kcr

PTSD, Vicarious Trauma, and the Emergency Frontline

Whose Trauma Is It Anyway?

Vicarious Trauma

The term "vicarious trauma" entered the lexicon in the 90s with McCann and Pearlman's article in the Journal of Traumatic Stress, among other works. They observed that mental health professionals were being affected by their exposure to the trauma of their clients (McCann & Pearlman, 1990). The outlook of the therapist mutated as they immersed themselves in the torment of the client's past. Of the affected schemas they identified, Dependency/Trust was afflicted with mistrust of others, for the client had been betrayed by the adults entrusted with their wellbeing. Safety became suspect - how could anyone be safe in a world that allowed such cruelty? Power was not guaranteed, as it had been ripped from their client and replaced with helplessness. Independence, Esteem, Intimacy, Frame of Reference - the therapist’s very concept of the world around them was changed as their client’s trauma slipped around their professional boundaries and seeped into their psyche. Vicarious trauma manifests its toll on the mental health professional in ways very similar to post-traumatic disorder (PTSD) itself, including intrusive thoughts, numbness, sleep problems, and hypervigilance (Rousseau, 2022).

Arguably, vicarious trauma would be the diagnosis best fitting the emergency frontline healthcare worker (EFH) who suffers from similar symptoms. While “frontline healthcare worker” is used in the age of COVID to describe any caregiver who interacts directly with patients, EFH is used here to identify the members of the healthcare team who encounter a patient in vital first hours that decide if they go to the hospital floor, a detox, home, or the morgue. These include emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and paramedics, police and firefighters in some systems, emergency physicians and nurses, patient care technicians (PCTs), and consulting providers such as trauma surgeons and neurologists who come to the emergency department (ED) to help guide the intricacies of care in which they are experts. Research on the impact EFH’s work imparts upon them often uses the term “secondary traumatic stress” (STS) which can be considered synonymous with vicarious trauma but should be kept separate from “burnout” and “compassion fatigue,” which are sometimes used interchangeably but are better viewed as distinct but related processes (Hunsaker, 2015). Studies have investigated the prevalence of vicarious trauma in subsets of EFHs, particularly emergency nurses, and found that as many as 39% meet criteria and 75% experience at least one symptom (Ratrout & Hamdan; Mansour, 2019). Certainly there is value to looking at the prevalence of vicarious trauma across mental and physical health disciplines, but is the phenomenon experienced by EFHs truly the same as that seen in other settings? While the contributions of the inpatient team must not be minimized, on the hospital floors the screaming has stopped, perhaps because a breathing tube has been passed through the vocal cords and made screaming an impossibility. The bleeding has been controlled - for as the moribund often state, “all bleeding stops eventually” - and the soiled clothes have been removed. The patient is now a resident of the hospital, as if they were never a member of the community, never a being from the same world as the caregiver at the bedside. Hospital floors are the world of vicarious trauma, where the patient’s pain and terror are experienced via empathy and rapport. The patient’s home, the street, and the emergency department are their own arena and their own phenomenon.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

When one is wrestling a woman whose arms and legs have been ripped off by a tractor trailer truck in order to control her delirious panic and save her life - is the trauma still vicarious? When tying someone to a bed and injecting them with sedating medications while they scream that the experience feels like when they were raped? The question was a point of some debate during the revisions that resulted in the DSM-V. Classically, the individual had to be the target of “actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others” (APA, 2000). While EFWs are the frequent targets of threats, verbal abuse, and physical assaults, these direct traumas are a distinct entity from those experienced while treating a patient in extremis (Gates et al., 2006; Touriel et al., 2021). Further, the definition required that the subject’s response be one of “intense fear, helplessness, or horror” (APA, 2000). This response is exactly what EFHs train to overcome. The ability to takes swift and evidence-based action in a crisis and suppress fear, helplessness, and horror is at the core of what makes an EFH. DSM-IV included the qualifying experience of being “confronted with” trauma, which certainly occurs in the ED, but this fails to capture the actual interaction, whether it be the sensation of breaking ribs during CPR or of a hand that was squeezing so tightly but then goes limp. The EFH may become a courier of trauma, shuffling into a quiet room to confront a family with news of the “unexpected or violent death, serious harm, or threat of death or injury experienced by a family member or other close associate” - all additional DSM-IV criteria for a trauma such as one that might result in PTSD (APA, 2000).

Recognizing these experiences as trauma, the DSM-V expanded its definition to include “repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s)” (APA, 2013). Surely then, the experience of the EFH has come to find its place in the scope of PTSD. Popular media would have us believe that the DSM has captured what it is to be an EFH surrounded by triggers for PTSD. In this world, the EFH walks into every shift with the knowledge that a bus full of hemophiliac toddlers will careen into a jagged glass factory after which terrorists will crash the MedEvac helicopter into the ambulance bay and take everyone hostage - all while a woman with ebola gives birth in a broken elevator as a colleague wonders if the child is his. But the ambulance and the ED are not Hollywood. The EFH trauma is exclusively failing lungs and sucking chest wounds. The ambulance is nearly guaranteed to pull up to a house in such a state of squalor that one wonders how a human being can have survived there. EMTs will respond to the alley where a person has fashioned their last possessions into a tent in which they may stay warm enough to survive the night while injecting the drug that has destroyed their life. An average shift in the ED will likely involve a quiet interview with a woman who can’t stop remembering the night she was raped or a man who, in the face of his brother’s recent death, has relapsed on heroin after eight years of abstinence. It may include telling someone that their persistent cough is due to lung cancer and the spots on their liver suggest it has already progressed past what modern medicine can remedy. Vicarious trauma is alive and well in the ambulance and the ED, as it is on the hospital floor or in the mental health professional’s office.

So vicarious trauma fails to incorporate the visceral experience and PTSD does not capture the empathetic burden of bearing witness. Where does this leave the emergency frontline? Perhaps with a term of their own...

Emergency Frontline Trauma

Where is the value in identifying this middle ground - this Emergency Frontline Trauma? The symptoms and treatments of vicarious trauma and PTSD overlap extensively. Is there any reason to distinguish the experience of the EFH or is this simply self-pity and self-importance? Well, like any illness the phenomenon can only be managed if it is specifically characterized and studied. If the experience of the therapist is different from that of the emergency nurse, then those conditions must be examined as the separate entities that they are. The person with a history of PTSD may have a single individual with whom they must come to some kind of peace or reconciliation but the physician may be unable to identify a single party who has caused her harm or damaged her sense of purpose. A mental health provider obtains a depth of understanding and familiarity with a client that an EFH could never match. Each entity possesses its unique qualities and warrants its own study so that caregivers weighed down by the past may thrive in the future.

Note: By virtue of being dedicated to the subject of trauma, this piece focuses on troubling aspects of emergency care. But as the endings of so many adventure novels and movies have celebrated, shadows are only cast in the presence of light. The work is a joy and a privilege. That realization alone is a weapon against the despair and emptiness of vicarious trauma and PTSD, if only one of many that must be employed to persevere on the difficult days and gloomy nights.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Gates, D. M., Ross, C. S., & McQueen, L. (2006). Violence against emergency department workers. The Journal of emergency medicine, 31(3), 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.12.028

Hunsaker, S., Chen, H.C., Maughan, D., & Heaston, S. (2015). Factors that influence the development of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in emergency department nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(2), 186-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12122

McCann, I. L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00975140

Ratrout, H. F., & Hamdan-Mansour, A. M. (2019). Secondary traumatic stress among emergency nurses: Prevalence, predictors, and consequences. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12767

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 1: Introduction to Trauma. [Boston University Course Materials]

Touriel, R., Dunne, R., Swor, R., & Kowalenko, T. (2021). A Pilot Study: Emergency Medical Services-Related Violence in the Out-of-Hospital Setting in Southeast Michigan. The Journal of emergency medicine, 60(4), 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.12.007

Yoga to help treat trauma & PTSD

Breathe in and out. Namaste!

Yoga has been used for quite sometime to help the individual ground themselves back to the central point when life is chaotic and they have lost focus on the important things. We have found that yoga can be,p those that have gone through some type of traumatic event and even for the treatment, individuals in the prison system and even PTSD.

PTSD is a very complex and challenging illness that can take over the lives of those who are affected. The use of Yoga for these individuals helps them by working both mind and body to form a focus point where the individual can feel a sense of safety and belonging. Yoga combines with psychology techniques we are able to see an improvement for these individuals and their recovery from their traumatic events.

I am a believer of Yoga to help not only treat PRSD but also other psychological and physiological illnesses. The way it help the individual focus and recenter allows the brain and body to sort of reset a little allowing the person to pause and gain mindfulness within their daily lives. We have seen the effects of Yoga within the prison system and now we see seeing it with the treatment of post traumatic stress disorder individuals. It was noted that “yoga seemed to be more effective than medicine” (Van der Kolk, 2014, pg. 209). I am sure that is many cases this is true but relying solely on one therapy could give a false sense of outcome and hope for the individuals involved. As I stated, yoga seems to be effective but it should also be used with other modalities to help increase the positive outcome of the therapy.

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 4: Pathways to recovery: Understanding approaches to trauma treatment. Blackboard, https://onlinecampus.bu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-9960461-dt-content-rid-63971458_1/courses/22sprgmetcj720_o2/course/module4/allpages.htm

van der Kolk, B. A., MD. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin.

The Neurobiology of Trauma

I believe that addressing the neurobiological aspect of trauma is vital in understanding the negative effects of trauma. Firstly, trauma is a term used to describe the experience or circumstances that occur which in turn have a negative effect on an individual. This can be quite devastating as one would imagine. Some may experience trauma on a daily basis while others may not. Regardless of the number of occurrences, trauma remains distressing and taxing for all that experience it. How a person responds can vary person to person, they may be in denial of the situation, they may show symptoms of depression, anger, anxiety, etc. There is no one clear set of boxes that a person must check off in order to state that they’ve experienced trauma.

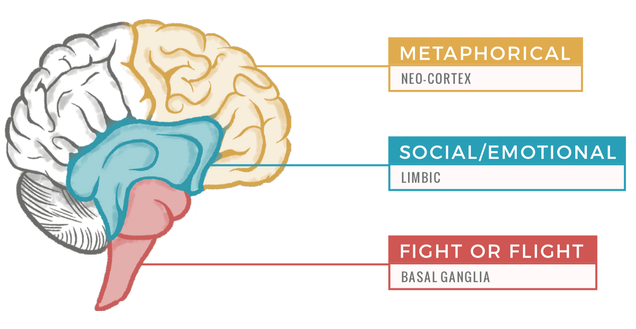

But what causes all of these symptoms to occur in the first place? There are various areas within the brain that tend to be the most affected by traumatic events. This includes the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, thalamus, and hippocampus. One of the issues that tends to come up when talking about trauma is how complex it is. Paul MacLean, a renowned physician and neuroscientist, explained the brain as being separated into three separate brains. Looking at his work can help us better explain trauma in terms of neurobiology. MacLean coined the term “triune brain”; which consisted of the reptilian brain, mammalian brain, and cerebral cortex. The reptilian brain includes the brain stem, cerebellum, and basal ganglia. This is where our autonomic nervous system comes into play, essentially holding all of our autopilot functioning like breathing, blood flow, etc. The mammalian brain is where one would find the thalamus, hypothalamus, amygdala and hippocampus. Otherwise known as the limbic system. This area of the brain is heavily involved in memory and responses. The limbic system connects with our reptilian brain to churn out an appropriate response. This connection is where our fight, flight, or freeze responses would occur. Then we have the cerebral cortex, this is where the right and left hemispheres, and the medial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortexes of the brain are located. These are the outermost layers of our brains, where our “higher-thinking” comes from. Things like intelligence, planning, organization, language processing/learning are all functions found within the cerebral cortex. Each of these “three brains” as outlined by MacLean are involved in how we respond to traumatic stimuli.

One major argument against this model is it focuses on a hierarchy of the brain. The idea being that the brain developed overtime as a result of evolution. Looking at the outline it would consist of the reptilian brain being developed first, then the mammalian brain and finally the cerebral cortex. Rather than the brain being triune, it has been suggested that it is adaptive and uses “adaptive prediction resulting from interdependent brain networks using interoception and exteroception to balance current needs, and the interconnections among homeostasis, allostasis, emotion, cognition, and strong social bonds in accomplishing adaptive goals” (Steffen et al., 2022). I do still believe that the triune brain model allows us to easily look at how the brain reacts to trauma and stressful situations. Which is why MacLean’s theory is still widely discussed today. Regardless of whether or not you believe in a more adaptive or triune layout of the brain, the information and things that are happening during stressful events remains the same.

I would also argue that if we were to use MacLean’s model to address a specific situation we would be able to do so in a way that was easily understandable to fellow listener’s. For example, let's say we live in a tropical climate like Florida, we’re halfway into a walk in the forest when we hear a rustle and see quick movement by our feet. Our brain perceives this event to be dangerous, there could be a snake nearby. The sensory information that we internalized, the noises and brief visuals were processed and sent to our thalamus and then relayed to the amygdala to rule out whether or not we were in a safe or unsafe situation. In our case it was deemed to be unsafe given prior knowledge of our surroundings. Due to our situation being seen as dangerous our hypothalamus then releases adrenaline and norepinephrine to trigger our fight, flight, or freeze response. Once that event occurs our cerebral cortex receives this information from the limbic system to create a memory based on the event. That way if another event similar to that one occurs the body will instantly flee, fight, or freeze. The information gets stuck. Sometimes this can be useful, like in this example where you would need to do something on the spot to avoid getting bit by a potential snake. On the other hand, this can also be detrimental to the individual in situations such as a Marine coming home after experiencing war trauma. Trying to integrate back into civilian life can be difficult when dealing with trauma related to war. Using this knowledge we can relate it back to real world situations to try and come up with solutions to address these negative effects.

Fortunately there are various options for therapy available to those who have experienced trauma. There is exposure therapy, EMDR, Yoga therapy, and much more. In having so many options available to address trauma, individuals are able to pick treatment best suited to their needs. Even within exposure therapy there are branches of different forms ranging from imaginal exposure, in vivo exposure, and flooding. The treatment that is ultimately chosen depends on the individual and what they’re comfortable with. What is very clear is that the neurobiology of the brain, what is happening behind the scenes, is equally as important and essential to understand.

Sources:

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 3: Neurobiology of trauma. Retrieved from https://learn.bu.edu/bbcswebdav/courses/22sprgmetcj720_o2/course/module3/allpages.htm.

Steffen, P. R., Hedges, D., & Matheson, R. (2022, April 1). The brain is adaptive not triune: How the brain responds to threat, challenge, and change. Frontiers in psychiatry. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9010774/

Burnouts among police officers

In Module 6, we've been presented an article, Routine work Environment Stress and PTSD Symptoms in Police Officers, that discussed the relationship between work environment and PTSD symptoms among police officers. The results showed that their work environment stress was most strongly associated with their PTSD symptoms and more specifically, variables such as gender and ethnicity resulted in having more negative social interaction and discrimination (Meguen et al., 2009). We further discussed the stigma surrounding police officers with mental illnesses and their concerns regards to requesting treatment due to fear of losing their jobs, having their license to carry a firearm taken away, being reassigned to a less stressful position, or being ridiculed by their peers and being seen as weak. While offering all the necessary resources to help better their mental health is crucial, being able to recognize the underlying cause to their problems is also important. Behind every police officer is a husband, a wife, a father, a mother, a friend, a coworker, and most importantly a human being. These qualities are often overlooked because of their heroic actions in the community, and places so much pressure on them to be the "hero." What we don't see is the emotional and physical exhaustion from responding to countless calls where they are expected to make split second decisions under pressure.

Most police officers, male and female, reported that the most frequent stressor was responding to violent family disputes, and the most highly rated stressor was being exposed to battered children. Though infrequent, another most highly rated stressors were killing someone in the line of duty and experiencing a fellow officer being killed. Male officers reported court appearances off duty and working second jobs as stressors while female officers reported experiencing lack of support from supervisors as a stressor (Violanti et al., 2016).

Reducing the amount of incidents that act as stressors may be impossible, but reducing the amount of time and workload police officers is exposed to stressful situations is more practical. Offering debriefings like CISM and overall organizational support is important for officers as it would help them deal with traumatic events that unfortunately comes with the occupation. On the other hand, reports of female officers feeling under-supported by their superiors reiterates how even though we are seeing an increase in female officers across police departments, some organizations are still having issues of discrimination. For that reason, there needs to be more training and education providing statistics and evidence on the positive aspects of women in policing. Overall, without addressing these stressors, more police officers will experience burnouts and significant mental health deterioration leading to depression and suicide.

Maguen, Metzler, T. J., McCaslin, S. E., Inslicht, S. S., Henn-Haase, C., Neylan, T. C., & Marmar, C. R. (2009). Routine Work Environment Stress and PTSD Symptoms in Police Officers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(10), 754–760. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b975f8

Violanti, Fekedulegn, D., Hartley, T. A., Charles, L. E., Andrew, M. E., Ma, C. C., & Burchfiel, C. M. (2016). Highly Rated and most Frequent Stressors among Police Officers: Gender Differences. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 41(4), 645–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-016-9342-x