Traumatic Divide

St. Louis city has a terrible reputation as being a dangerous city overrun by crime. Most of the crime is centered in two districts of northern St. Louis City. “There is this conception of the city as crime-ridden throughout,” says University of Missouri–St. Louis criminology professor Richard Rosenfeld. Looking at the homicide rate, which ranks at or near the top among U.S. cities each year, it appears that the violent crime risk is the same everywhere throughout the city. Rosenfeld’s research says otherwise: “It’s very high in a few neighborhoods on the north side, and in and around Dutchtown, and hardly anywhere else.” (Woytus, 2019).

Working for the Federal Public Defender’s Office in St. Louis, MO, I represent people accused of federal crimes. Most are young, African-American men, indigent, with at least one mental health diagnosis. Regardless of the type of crime they are accused of committing, their personal stories of trauma incurred as children, events they have witnessed, or violence they have committed to simply survive is a recurring theme. Many of them grew up in the aforementioned districts.

Delmar Boulevard is referred to as a “divide” in the city. South of this divide, you will find $500,000 homes and wine bars. This southern neighborhood, according to U.S. Census data, is 70 percent white. To the north of the divide: collapsing houses, gang signs spray painted on every corner, trash in the streets, and neglected infrastructure. The neighborhood is 99 percent black. “You have a division between the haves and have-nots,” explained Carol Camp Yeakey, founding director of the Center on Urban Research & Public Policy and Interdisciplinary Program in Urban Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. “People on one side are prospering, and the people on the other side are not” (Harlan, 2014). The north city has a poverty rate around 40%. Around 25% of residents have not finished high school. There are distinct socioeconomic, cultural, and public policy differences to the north and south of the divide.

According to Elijah Anderson, “The inclination to violence springs from the circumstances of life among the ghetto poor—the lack of jobs that pay a living wage, the stigma of race, the fallout from rampant drug use and drug trafficking, and the resulting alienation and lack of hope for the future” (Cullen, Agnew, & Wilcox, 2018). These conditions create a subculture of violence that can be found in these neighborhoods. In “The Code of the Streets,” Anderson describes the formation of the code among those who experience “a profound sense of alienation from mainstream society and its institutions, who see no positive place for themselves in dominant culture, yet sense a need for dignity on some grounds, some clear sense of personal ‘respect’” (Cullen, Agnew, & Wilcox, 2018).

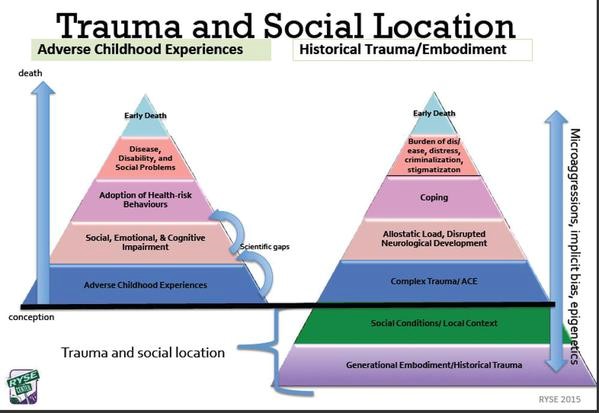

Many researchers have focused their studies on biological and environmental causes of trauma. A cultural divide and lack of protective factors affect an individual’s response to trauma. A poor family environment, with social factors such as poverty and abuse, adversely affect a person’s natural state.

(Advocate, n.d.).

In comparison to Caucasians, ALANAS (African/Black Americans, Latina/Latino Americans, Asian/Pacific Islander Americans, and Native Americans) are more likely to develop PTSD after experiencing a traditionally defined traumatic event (Helms, Nicholas & Green, 2010). The men I work with describe seeing family members shot in the streets, friends gunned down in drive-by shootings, experienced sexual assaults by family members, and have no safe space to call home. Much like the veterans that Van Der Kolb spoke about, these men’s only support system are those that live the same life and have had experienced the same traumas.

I focus on this population of people to demonstrate how two different sets of life experiences, different skill sets, and how the lack of support systems contributes to PTSD. People fortunate enough to receive early intervention within a safe place are able to better understand the negative feelings they are having and how to put them into perspective. A trauma victim heals within strong family environments and positive peer relationships. The way a person makes sense of life events contributes to their recovery. Post traumatic growth occurs for those that are resilient and are able to gain an increased sense of personal strength and greater appreciation for life in general (Rousseau, 2020). It is imperative that mental health professionals and trauma researchers work toward developing more comprehensive understandings of the experiences of traumas for people growing up in poverty or unsafe neighborhood environments. In doing so, we can help trauma victims that do not have a safe place or positive support structures begin to heal and experience their own post traumatic growth.

References

Advocate. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.peace4gainesville.org/advocate.html.

Cullen, F. T., Agnew, R., & Wilcox, P. (2018). Criminological theory: Past to present: Essential readings. New York: Oxford University Press.

Harlan, C. (2014). In St. Louis, Delmar Boulevard is the line that divides a city by race and perspective. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/in-st-louis-delmar-boulevard-is-the-line-that-divides-a-city-by-race-and-perspective/2014/08/22/de692962-a2ba-4f53-8bc3-54f88f848fdb_story.html?utm_term=.2bb00a09b6b1.

Helms, J., Nicolas, G., & Green, C. (January 01, 2010). Racism and Ethnoviolence as Trauma: Enhancing Professional Training. Traumatology, 16, 4, 53-62.

Rousseau, D. (2020). Module 1. Retrieved from https://learn.bu.edu/webapps/blackboard/execute/displayLearningUnit?course_id=_65989_1&content_id=_7783430_1&framesetWrapped=true.

Woytus, A. (2019). These are the St. Louis neighborhoods with the most crime-and this is what the police and residents are doing about it. Retrieved from https://www.stlmag.com/news/crime-data/.