Home

Testimony From a Child

The Sixth Amendment is the constitutional right for all offenders within the United States to be afforded the right to a trial with very specific requirements. Specifically, an offender has the right for a public trial without delay, the right to a lawyer, the right to face your accusers, and the right to an impartial jury. A portion of the rights afforded for a fair trial are having a witnesses testify as to the facts of the case, but what happens when the testimony is elicited from a child?

In the court of law, a subpoena holds the power to mandate any individual testify in situations that the court deems necessary. If a situation arises where the witness is a child, a subpoena can legally be used identically as if the witness were an adult. Respectively, “a parent who fails to bring a child to court after the child has been subpoenaed can be found to be in contempt of court, which can result in fines or even jail time” (Criminal Defense Lawyer). In this sense, serious concerns of responsibility arise when exposing children to the stressors of testimony in a courtroom, let alone recalling memories which are sensitive in nature that may induce trauma and horrific memories. Parents of these children have legitimate concern if their children become testifying witnesses which may hold weight in sentencing dangerous people. Witness intimidation, threats, or even violence is a serious issue when dealing with witness testimony in high profile cases.

In certain situations, “children can take the stand and testify in court, and the Judge has the ability to decide whether this is a good idea or not” (Rosen). Children can be called upon to testify in a multitude of situations. Often children are in the wrong place at the wrong time, viewing horrific incidents that their recollection is needed for. Homicides, vicious assaults, and car accidents resulting in death, are just a small list of criminal offenses that may be witness by a child. Most commonly, children are called to testify at divorce proceedings involving their own parents. The stress, anxiety, and trauma that is associated with taking the sides of your parents is a situation that no child should have to bear. Children of a young age are still mentally developing and are often unaware of the consequences of the words they are saying. It is understood “that infants and children differ in activity, emotionality, and general sensitivity to stimuli” (Module 1.3), thus creating varying and inconsistent reactions to depicted trauma. The testimony of a child can also be considered non-credible, considering their perception is that of an individual with no life experience or understanding of parental conflict.

The trauma of recalling sensitive events is authentic. Testifying in front of a large group of strangers, in a new and intimidating environment, about a topic that is disturbing in nature, is a recipe for trauma. Luckily, courts in certain states have enacted laws which have demonstrated sensitivity to these situations. Specific jurisdictions have allowed courtrooms to be closed to any audience members during the times of a child’s testimony. In some states, “child witnesses can also visit a courtroom before testifying to familiarize themselves with the surroundings and with court proceedings” (Criminal Defense Lawyer). Certain jurisdictions have even allowed testimony to be recorded to be played at a later date, further removing a child from in person testimony.

Ultimately, situations will arise where children are needed to testify. Legislation should be adopted which is accepted within all jurisdictions, prioritizing the potential trauma that is experienced by a child during testimony at court. Universal safeguards and protocols must be enacted which will be legally binding for all courts, prosecutors, and defense counsels to adhere to. Parents have the horribly difficult task with keeping their children safe, and unfortunately in the court of law, this protection can be ripped from them at a moments notice.

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 1: Thinking Like a Forensic Psychologist. Boston University Metropolitan College Forensic Behavioral Analysis. Blackboard.

Rosen Law Firm (2022) The Child’s Preference and Testimony in Court. Retrieved on August 8, 2022 from https://www.rosen.com/child-custody-course/childs-testimony-in-court/

Criminal Defense Lawyer (2022) Can A Judge Order My Child to Testify? Retrieved on August 9, 2022 from https://www.criminaldefenselawyer.com/resources/criminal-defense/juvenile/can-a-judge-order-my-child-testify-a-criminal-case

Waltrip Firm (2018 May 31) The Child Witness. Retrieved on August 9, 2022 from https://waltripfirm.com/child-witness-competency/

Times of Malta (2016 Oct 23) When Children Take the Witness Stand. Retrieved on August 9, 2022 from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/when-children-take-the-witness-stand-what-support-do-they-receive.628766

Solitary Confinement, Mental Illness, and Trauma

The utilization of solitary confinement in prisons is extremely harmful mentally, physically, and socially. Moreover, the effects of this extreme isolation for those with mental illnesses is especially damaging, and can cause further trauma and worsen the mental disorder. Despite the vulnerability, those with mental illnesses are both over represented in prisons and in solitary confinement units. Furthermore, solitary confinement is particularly dangerous when utilized on one with trauma of any kind, whether from past abuse, a mental illness or prison itself. Efforts must be taken to remove solitary confinement from being used on those who are mentally ill, and only enforced if a crime within prison is heinous, or the inmate is a specific threat to others or him/herself. The confinement itself is not worth the trauma it creates, as it is largely neither cost effective, nor solves problems only exacerbates them. Moreover, there is an argument to be made that solitary confinement, specifically for those who are mentally ill violates the eight amendment, and that it should be removed. Overall, solitary confinement, specifically for those who are mentally ill or have undergone extreme trauma can be likened to torture and worsen mental health symptoms.

Solitary confinement is defined as “the physical isolation of individuals who are confined to their cells for 22.5 hours or more per day” (Leonard, 2020). The inmates are “encased in concrete and steel” with enforced steel walls, and doors (Skibba, 2018). The cell contains a metal bed, small toilet and often not even a window for natural light. The entirety of the cell is about the size of a small elevator where the inmates are locked up like animals in a cage (Skibba, 2018). It is common for inmates to loose their grip on reality, experiencing the same smells, slights, and limited range of motion every day on repeat (Skibba, 2018). The length of time one can be confined can range anywhere from a couple of hours to days, to weeks and even to years. One inmate even spent 40 years in solitary confinement (Leonard, 2020).

The use of solitary confinement is used as a form of punishment for three main reasons. The first is disciplinary segregation, or punishment for breaking rules, the second is temporary segregation, or being isolated due to a physical altercation, and the third is administrative segregation, or isolation of one who presents an ongoing threat to the safety of themselves and, or others (Leonard, 2020). Further, while its original use was for protective custody or housing violent prisoners, the use of solitary confinement is now used predominantly for minor crimes. While nations such as Germany utilize isolation for serious acts of violence only, the United States frequently uses isolation to punish for minor offenses and inmates breaking basic rules. A study conducted in Illinois in 2015 found that 85% of those incarcerated who had been placed in solitary confinement had been done so for minor offenses. Moreover, the United States uses solitary confinement for longer periods of time than any other nation, with up to 80,000 people in isolation per day, not including juvenile facilities (Leonard, 2020)

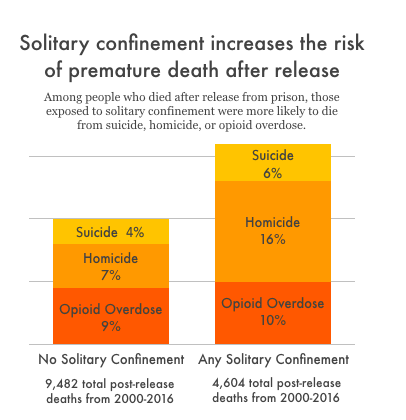

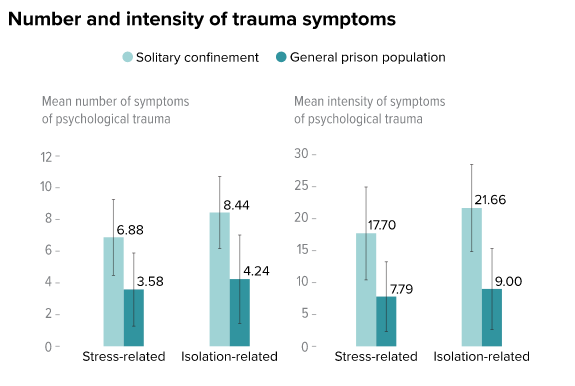

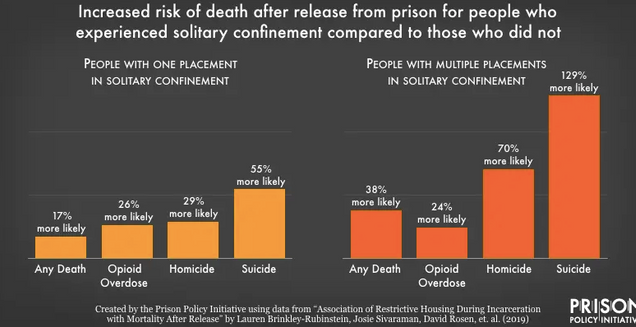

The effects of solitary confinement range from physical, to emotional and mental problems depending on the length of time one is isolated for. Mental health problems can include: anxiety and stress, depression, hopelessness, anger, irritability, hostility, panic attacks, hypersensitivity to sounds and smells, hallucinations, paranoia, poor impulse control, social withdrawal, violence, psychosis, fear of death, and even suicide and self harm (Leonard, 2020). Suicides occur more in segregation units than anywhere else in the prison (Metzner, 2010). In fact, around half of what is deemed, “successful suicides” occur housed in solitary confinement. Due to the limited methods for suicide in both isolation regular cells, creative and often gruesome methods of suicide are utilized and attempted (Dillon, 2019). Furthermore, even if the inmate is both sane and has no mental disorder entering solitary confinement, some have been stated to leave with mental health symptoms and paranoia that were not present prior (Dingfelder, 2012). While, “Prisons and jails are already inherently harmful, and placing people in solitary confident adds an extra burden of stress that has been shown to cause permeant changes to peoples brains and personalities” (Herring, 2020). Studies have even stated that after release from prisons, those who have undergone time in solitary confinement are more likely than others to either die via suicide, or reoffend and come back to prison. The data from the JAMA study in North Carolina found that those in isolation were 24% more likely to die within the first year of release from prison. Specifically, those in isolation were 78% more likely to commit suicide and overall 127% more likely to die of an opioid overdose (Stagoff-Belfort, 2019).

An extensive problem one endures in solitary confinement is the obvious presence of social isolation. People are not created to be alone, and be isolated beings. Emotional, social and physical contact are largely necessary for one to live. Without the comfort of others, and constantly being alone, ones risk for depression and anxiety due to the intense loneliness increases. Researchers note the powerful connection between isolation and psychiatric illnesses, in addition to worsening one’s current mental illnesses (Cruel, 2019). Social isolation can also lead to elevated cortisol levels which are related to an increase in blood cholesterol and blood pressure (Dillon, 2019) The extreme loneliness, and solitary confinement itself “requires people to learn to live in a world without people…It is the medial of meaningful social engagement with others” (Skibba, 2018). When released they are often incapable of living back in either normal society or amongst the general prison population. “They are overwhelmed with anxiety…they become frightened of other human beings” (Dingfelder, 2012).

Moreover, there are many physical health problems that can result from isolation. These physical health effects include: chronic headaches, deteriorated eyesight, digestive problems, dizziness, lethargy and fatigue, heart palpitations, hypersensitivity to light and noise, loss of appetite, sleep problems, weight loss, and muscle and joint pain. Further, due to the lack of natural light, vitamin D deficiency can occur leading to weakness, depression, and brittle bones. Further, confined to their cell, inmates undergo little to no physical activity. This often leads to a difficulty to manage high blood pressure, heart diseases and further, one becoming more anxious, hopeless and depressed (Leonard, 2020). Moreover, researchers Jules Lobel and Huda Akil state that the utilization of solitary confinement can alter various brain components such a the hippocampus which is involved in stress and memory. The damage can lead to a loss of emotional stress control, decreased cognitive processes, and severe depression. Research has found that even being in solitary for only a few days, ones electroencephalogram test results demonstrate abnormalities that reflect states of delirium and numbness (Cruel, 2019). Jack Abbott, who spent a large amount of time in solitary confinement stated that “the lethargy of months that add up to years…alone…entwines itself about every physical activity in the living body and strangles it slowly to death” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1781).

While the effects of solitary confinement contain traumatic elements that impact even regular prisoners, its effects are worsened when one has already undergone trauma or has a mental illness. One study cited that the effects of solitary confinement “are analogous to the acute reactions suffered by torture and trauma victims” (Hagan, 2017). The implementation of a traumatic event on top of one who has undergone intense trauma can lead to self harm and possible suicidal attempts (Hagan, 2017). Studies have identified that various aspects that occur in isolation and the psychological stressors that occur are similar to and “can be as clinically distressing as physical torture” (Dillon, 2019). Similarly, those who are mentally ill experience elevated rates of their symptoms including anxiety and hallucinations after solitary confinement (Hagan, 2017). The lack of social contact, stress, isolation and trauma from solitary confident can “exacerbate symptoms of illness or provoke recurrence” (Metzner, 2010). All in all, the risk of “something more permanent and disabling” in terms of trauma is exacerbated if one has preexisting mental trauma (Dillon, 2019). Furthermore, in addition to worsening symptoms access mental health treatment options are limited and often unavailable while in isolation. There is no group or individual therapy, life skill activities, or other interventions allowed. The most a mental health professional can discuss with the inmate is asking if they are okay and coping with the isolation (Metzner, 2010). Those who are mentally ill are also more likely to commit suicide or engage in self harm acts after being released from isolation.

Moreover, excessively problematic is the amount of those who are mentally ill who are sent to solitary confinement. As stated, they are at greater risk for suicide and exacerbating mental health issues that other inmates, however continue to be sent to isolation. Due to various mental illnesses, prisoners can often act and “exhibit bizarre, annoying, or dangerous behavior and have higher rates of disciplinary infractions than other prisoners” (Metzner, 2010). This is often seen as said individual both breaking the rules and acting out. Instead of understanding and assessing whether the behaviors are a result of a mental disorder, the inmate is often sent straight to solitary confinement. Furthermore, once in isolation, the inmate can exhibit further misconduct due to the further trauma and isolation, lengthening the time in solitary confinement (Metzner, 2010). Moreover, the NCCHC stated that the “placement of inmates with serious mental illness in settings with extreme isolation is contraindicated because many of these with psychiatric conditions will clinically deteriorate or not improve” (Metzner, 2010). Similarly concerning trauma, those sent to isolation due to misbehaviors bizarre behavior may be due to fear and anxiety not the anger and frustration that corrections believes they are identifying. Along these lines, more than 43% of women as opposed to 12 percent of men have been sexually assaulted and undergone sexual trauma, and the stressors and further trauma in prisons often worsens their conditions and anxiety (U.S Department of Justice, 1998). For example acts of self violence in women have been declared as criminogenic and are often punished with said isolation as they are declared difficult and untreatable (Hannah-Moffat, 2006). Staff see acts of self harm as an attempt to manipulate staff or simply acting out due to anger, and send them straight to isolation, instead of seeing the issue for what it really is, a cry for help, a response to trauma, or extreme symptom of a mental illness (Dillon, 2019).

The severity of psychological harm has been even been described as being more “debilitating than physical harm” (Dillon, 2019, 291). In addition to this, the physical and emotional harm and trauma should trigger a necessary response in law makers to rid of solitary confinement as it largely violates the eight amendment, or the utilization of “cruel and unusual punishment.” In utilizing the word “cruel,” the courts “implied that cruel meant something inhumane and barbarous” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1761), and it can be argued that the combination of all the factors presented to an inmate in solitary confinement make this form of isolation uniquely devastating” (Cruel, 2019 , pg. 1773). Specifically concerning those with mental health issues, these individuals are undergoing punishment that denies them from access to life changing treatment and help. In putting those who are mentally ill in isolation, “confinement causes consistent, and sometimes irreversible psychological and physical harm” (Dillon, 2019, pg. 268), which can constitute as a cruel and unusual punishment, no matter the crime committed (Dillon, 2019). Further, the use of long term solitary confinement has been deemed both cruel and unnecessary and can lead to “irreparable human damage” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1783). When visiting Cherry Hill Prison, Charles Dickens noted that the use of solitary confinement and the “slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the mind to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1775), holding its usage to be both “cruel and wrong” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1773). While it does not involve torture to the body specifically, using “whipping, the breaking wheel, [and] disembowelment” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1778), “it is a quiet and invidious form of punishment that amounts to torture” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1779). Further, the use of solitary confinement when reintroduced in the 1980s can be declared unusual, as it “never became a “usual” practice after it first arose…nearly every date explicitly rejected the practice after they saw the detrimental effects it had” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1759).

Significantly, there is “no evidence that administrative uses of segregation have any positive effect reducing or controlling gangs in prison” (Skibba, 2018). Further, the solitary confinement is not cost effective, often worsens the issues that are attempted to be solved, including aggression and hatred towards guards and other inmates, and does not achieve the overall outcomes (Leonard, 2020). The effects of solitary confinement on general inmates and specifically those with mental illness and distinct trauma is massive, and largely not worth the costs it creates. Due to research and analysis regarding this topic, many mental health professionals have attempted to eliminate solitary confident for mentally ill inmates. Instead these inmates who violate the rules inside prisons will be moved to a clinical setting where they will be treated at high levels consistently with the aim of “promoting treatment adherence and prosocial behaviors”(Venters et al, 2014). Moreover, this plan, created by the NYC Department of Corrections and Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, planned to establish mental illnesses in terms of serious to mild and moderate in order to create specific plans of violating prison rules. Those with mild behavioral problems will have more specific rules and regulations while in prison such as no outside time and recreational activities, instead of lengthily solitary confident (Venters et al, 2014). While, there is some credence to solitary confinement being utilized for dangerous criminals who are a danger to others and themselves, said confinement should be limited to inmates whose actions are as such. Isolation should not be given for minor offenses and small outbursts, and moreover the inmate responsible for each act thought to be punished should be assessed thoroughly and screened for prior intense trauma or mental illness that may have been responsible for said action. Standards of assessment should be rigid and programs such as the STAIR model are taking a step in the right direction. This model includes screening, triage, assessment, intervention and re-intervention, with a large focus on screening for mental illnesses and trauma, before intervention and treatments are implemented (Simpson, 2022). While efforts such as these are being considered, studied, and understood as growing in necessity, more needs to be done to remove and place restrictions on solitary confinement in prisons.

Resources:

Bartol, C., & Bartol, A. (2021). Criminal behavior: A Psychological Approach (12th ed.). Boston: Pearson. https://reader.yuzu.com/reader/books/9780135618813/epubcfi/6/2[%3Bvnd.vst.idref%3Dcover]!/4/2%4054:44

Calloway, K. (2019). I Spent 16 Months in Solitary Confinement and Now I’m Fighting to End It. Retrieved 11 August 2022, from https://www.aclu.org/blog/prisoners-rights/solitary-confinement/i-spent-16-months-solitary-confinement-and-now-im

CRUEL, UNUSUAL, AND UNCONSTITUTIONAL: AN ORIGINALIST ARGUMENT FOR ENDING LONG-TERM SOLITARY CONFINEMENT. (2019). American Criminal Law Review, 56(1759), 1759-1783. Retrieved from https://www.law.georgetown.edu/american-criminal-law-review/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2019/06/56-4-Cruel-Unusual-and-Unconstitutional-An-Originalist-Argument-for-Ending-Long-Term-Solitary-Confinement.pdf

Dillon, R. (2019). Banning Solitary for Prisoners with Mental Illness: The Blurred Line Between Physical and Psychological Harm. Northwestern Journal Of Law & Social Policy, 14(2), 266-292.

Dingfelder, S. (2012). Psychologist testifies on the risks of solitary confinement. American Psychological Association, 43(9).

Fenster, A. (2020). New data: Solitary confinement increases risk of premature death after release. Retrieved 11 August 2022, from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/10/13/solitary_mortality_risk/

Hagan, B., Wang, E., Aminawung, J., Albizu-Garcia, C., Zaller, N., & Nyamu, S. et al. (2017). History of Solitary Confinement Is Associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms among Individuals Recently Released from Prison. Journal Of Urban Health, 95, 141-148. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0138-1

Hannah-Moffat, K. (2006). Pandora's Box: Risk/need and gender responsive corrections. Criminology & Public Policy,5(1), 183–192

Herring, T. (2020). The research is clear: Solitary confinement causes long-lasting harm. Retrieved 10 August 2022, from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/12/08/solitary_symposium/

Leonard, J. (2020). Effects of solitary confinement on mental and physical health. Retrieved 10 August 2022, from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/solitary-confinement-effects

Metzner, J., & Fellner, J. (2010). Solitary Confinement and Mental Illness in U.S. Prisons: A Challengefor Medical Ethics. Journal Of The American Academy Of Psychiatry And The Law, 38(1), 104-108.

Simpson, A., Gerritsen, C., Maheandiran, M., Adamo, V., Vogel, T., & Fulham, L. et al. (2022). A Systematic Review of Reviews of Correctional Mental Health Services Using the STAIR Framework. Front Psychiatry, 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.747202

Skibba, R. (2018). The Hidden Damage of Solitary Confinement. Retrieved 10 August 2022, from https://knowablemagazine.org/article/society/2018/hidden-damage-solitary-confinement

Stagoff-Belfort, A. (2019). Study Links Solitary Confinement to Increased Risk of Death After…. Retrieved 10 August 2022, from https://www.vera.org/news/study-links-solitary-confinement-to-increased-risk-of-death-after-release

U.S Department of Justice. (1998). Women Offenders: Programming Needs and Promising Approaches. National Institute of Justice

Venters, H et al. (2014). Solitary Confinement and Risk of Self-Harm Among Jail Inmates. American Journal Of Public Health, 104(3), 442-447.

The Native American Children

LAWS MUST BE DEVELOPED FOR STATES

TO PUNISH

Sexual Abuse in the Native American Population

In 1786, the United States established its first Native American reservation and approached each tribe as an independent nation. This policy has remained intact for over one hundred years. Since the establishment of the reservations, State laws have been restricted to State territory. If there is a charge of sexual child abuse on a reservation, the State law enforcement cannot intervene.

Child sexual abuse is defined as an adult's use of a minor to satisfy sexual needs. Child sexual abuse is defined as a crime within State law. However, on Native American reservations, tribes create definitions within their own tribal codes to satisfy their community and law enforcement standards. It is also illegal for state authorities to enforce state laws on reservations. Most cases of child sexual abuse develop gradually over time, and the offender is known to the child in 90 percent of cases (Miller-Perrin & Perrin, 2007). According to the CDC defines obese kids as students who were greater than the 95th percentile for body mass index, based on sex-and-age specific reference data from the 2000 CDC growth charts (CDC.gov).

According to the CDC, the group that “Had Sexual Intercourse For The First Time Before Age 13 Years Among American Indian or Alaska Native Students United States, High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2019”

| Year % | Total % | Total Lower CI Limit | Total Upper CI Limit | Total N | Female % | Female Lower CI Limit | Female Upper CI Limit | Female N | Male % |

| 2019 | 4.7† | 1.5 | 13.9 | 109 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 54 | N/A |

| Male Lower CI Limit | Male Upper CI Limit | Male N |

| N/A | N/A | 55 |

The results were 109 students that were identified for this survey (CDC.gov). The confidence intervals for males these children were 1.5 to 13.9. These stats are not representative of the population. Mainly, this group is underrepresented because of the barriers to the reservations

The Deindividuation on Reservations

There are many theories that can be applied to this social issue. Here, Social Learning and Deindividuation are explored. Social Learning is a progressive advancement from classical and operant conditioning. Social Learning theorizes that human behavior is “based on learning from watching others in the social environment. On the reservations females and males alike learn than the sexual violation of little girls has a small risk value (Rousseau, 2022). Violators of children cannot be punished by state law enforcement officers. Reservation authorities are not usually contacted when a child sexual abuse occurs. Watching children being sexually abused without punishment, encourages others to repeat the same behavior (Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. 106). Deindividuation is the encouragement by others that a person is not present. Their anonymity can lead a factor of their victimization. A sexual predator can lose their identity and becomes part of the violating pack. This feeling generates a "loss of self-awareness, reduces concern over evaluations from others, and a narrowed focus of attention" (Baron & Byrne, 1977, as cited in Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. 120). When combined, these process may lead to the high rate of sex crime against children on the reservations.

Confirmed Maltreatment

The Impact Of Culture

- The article focuses on the impact of culture on the response of Native American parents to interventions concerning child abuse and neglect and child protection.

- It has been noticed that Native American parents react in a manner that cause childcare protection practitioners to view them as resistant and uncooperative.

Foster Care

- In some of the cases where the abused child is placed in foster care,

- it is not unusual for the parents to abandon their child and discontinue contact with the foster care agency.

A complicated legal arrangement

Out of the 574 American Indian Tribes in the U.S., only 200 are under the FBI's jurisdiction. This jurisdiction is a collaboration between the FBI and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Justice Services. "The federal government has a unique political and legal relationship with the 573 federally recognized tribes. The tribes are sovereign and have jurisdiction over their citizens and land, but the federal government has a treaty obligation to help protect the lives of tribal members" (FBI, 2022). This "trust responsibility," can be extended to give rights to children in the State that the incident occurs.

The array of Supreme Court decisions and federal laws that followed resulted in a complicated legal arrangement among federal, state and tribal jurisdictions, making it difficult for survivors of sexual assault to find justice.

You know the signs that you need to take better care of yourself when: You feel mentally or physically exhausted, overwhelmed or stretched too thin. Friends and family tell you you're working too hard, or have to remind you to take a break. You've worked 70- or 80-hour weeks.

Reference:

FBI, (2022). Indian Country. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/violent-crime/indian-country-crime

Pope, N. LMSW (2009) Miller-Perrin, C. L. & Perrin, R. D. (2007). Child maltreatment: An introduction, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 475 pp., Journal of Public Child Welfare, 3:1, 109-110, DOI: 10.1080/15548730802694918

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 1: Thinking Like A Forensic Psychologist. Boston University Metropolitan College Forensic Behavioral Analysis. Blackboard.

Stop Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is a significant global human rights issue, and sadly since human trafficking is covert, and since reporting is inconsistent, accurate data is scarce. People who are victims of human trafficking can be of any race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or nationality. Trafficking occurs to adults and minors across American communities, whether in the suburbs, rural areas, or urban areas. Various reasons may contribute to the victimization of these individuals, such as homelessness, runaway status, abuse, neglect, and a lack of safety at home due to violence. Millions of people across the globe are trafficked every year - including here in the United States (Department of Homeland Security, 2022).

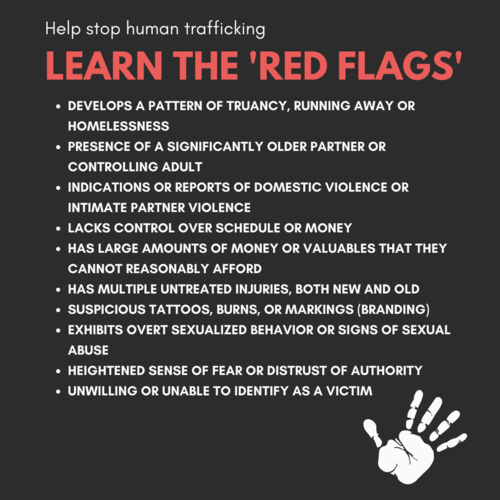

In the meantime, human trafficking is something that everyone is capable of discovering. There are many red flags and indicator signs that can help identify a human trafficking situation, such as; signs of physical abuse, poor living conditions, is the person fearful, timid, or submissive, does the individual appears to be coached on what to say, or does that person have freedom of movement (Department of Homeland Security, 2022). In light of this, there are numerous ways to support these victims of human trafficking once you have noticed these red flags and indicators. For instance, initiating a conversation in private, providing support and empowerment, listening to their comments and concerns, supporting their decisions, offering to help, and finally, if you believe that you have identified someone in the trafficking situation, alert law enforcement immediately (Supporting Victims of Human Trafficking-Valley Crisis Center, 2022). The National Human Trafficking Hotline is 1-888-373-7888, a 24-hour, toll-free, multilingual anti-trafficking hotline.

Nevertheless, there are simple ways to get involved and make a real difference: raise awareness of the issue on a local, regional, and national level, fundraise for anti-trafficking organizations, volunteer for anti-trafficking organizations, and promote anti-trafficking legislation (Public Service Degrees, 2020). The trauma suffered by survivors of human trafficking can often last a lifetime, both psychologically and physically. All anti-trafficking efforts should incorporate trauma-informed efforts to support survivors effectively, including the criminal justice system and victim services. When deploying prevention strategies and engaging with survivors, trauma-informed coping strategies and media reporting should also include a trauma-informed approach—getting trauma-informed means responding to the impacts of trauma on a person's life on a strengths-based approach. Human trafficking victims should be treated to minimize the likelihood of re-traumatizing them by recognizing signs of trauma and designing all interactions with them accordingly. To address survivors' unique experiences and needs, this solution focuses on creating a sense of physical, psychological, and emotional safety and well-being (US Department of State, 2021).

Sources:

Department of Homeland Security. (2022, April 13). What Is Human Trafficking? | Homeland Security. DHS. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/what-human-trafficking

Supporting Victims of Human Trafficking – Valley Crisis Center. (2022). Valley Crisis Center. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.valleycrisiscenter.org/supporting-victims-of-human-trafficking/

US Department of State. (2021, January 10). Identify and Assist a Trafficking Victim. United States Department of State. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.state.gov/identify-and-assist-a-trafficking-victim/

Public Service Degrees. (2020, August 14). Be the Change: How You Can Help End Human Trafficking. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.publicservicedegrees.org/403.shtml/

A Private War: Why PTSD Is Still Overlooked

Why PTSD is still overlooked: I came across a very interesting article in the New York Times that was published by Dani Blum, but was information from Van der Kolk and other very prominent researchers and experts. I wanted to address one of the comments by one of the expert that mention: "Some experts say this pervasiveness has diluted the meaning of PTSD. The disorder stems from severe trauma, said John Tully, a clinical associate professor in forensic psychiatry at the University of Nottingham in England. “We’re talking life-threatening or close,” he said. The term loses its meaning when people apply it too broadly, he said — and PTSD means more than wrestling with the aftermath of an upsetting event." This comment struck me because in the beginning of the article it mentions that 70 percent of adults in the United States experience one traumatic event and about only 6 percent will develop PTSD the bulk being women. I feel a lot of PTSD in women can stem from childbirth as mentioned a women was diagnosed with PTSD after she delivered a stillborn baby, she expressed after leaving the hospital forgetting how to even get home and feeling like she had arrived from mars. I feel that not only is PTSD being overlooked but it is also being overlooked in women who have given birth. The rewarding opportunity to bring life into the world is such an honor as a mom but in that same sentence can be so difficult especially for new moms. An article from the The Atlantic expressed the misdiagnosis of postpartum depression with postpartum PTSD which differ in the since that postpartum depression is commonly associated with sadness, trouble concentrating, and having a hard time finding happiness in activities versus postpartum PTSD is associated with flashback and intrusive memories. For mothers this traumatic experience can come before or during pregnancy and can be associated with severe morning sickness, bad reactions to fertility etc or when your baby has medical problems during labor.

Based on these articles and how much postpartum PTSD, I know of mothers who experienced things that these exact women experienced during giving birth and how it has had such a long term effect on them. At the time I did not consider their symptoms to be associated with PTSD but I know how it made them feel, even looking at some women who can't produce milk for their children through their whole pregnancy and it makes them feel like a failure of a mother and as if they aren't able to provide for their child. For some women this is such a traumatic event, especially as a mom. Which makes some women afraid to have more children because of some of the complication they experienced with their first kid.

Overall, my purpose of this article was to just to shed light on how PTSD is being overlooked in many different aspects. And so many people go without getting help because you have experts that make comments like the one above not wanting to dilute the word PTSD and neglecting the many that suffer. What may not be considered a life-threatening traumatic event to some" can seem like the end of the world to many.

References:

Blum, D. (2022, April 4). A private war: Why PTSD is still overlooked. The New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/04/well/mind/ptsd-trauma-symptoms.html

Strauss, I. E. (2015, October 2). The mothers who can't escape the trauma of childbirth. The Atlantic. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/10/the-mothers-who-cant-escape-the-trauma-of-childbirth/408589/

Indigenous Generational Trauma

The concept of trauma and its aftereffects have long been little understood. People deal with traumatic situations differently and what may not affect some can scar others for life. Its complexities are still not entirely understood and the aftereffects of trauma, even less so. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other disorders that develop as a result of experiencing a traumatic event are at the forefront of this class. I chose to delve into the effects of intergenerational trauma in individuals. Specifically, looking into the effects of intergenerational trauma on indigenous groups piqued my interests. My mother is Ecuadorian and natively indigenous to that country, so many of the experiences of Canadian Native Americans and are similar to hers and that of her family. Trauma, in this context, is not an isolated event or incident. Rather, it spans decades and even centuries starting with distant ancestors and accumulating to the experiences of the individual today. It’s a tragic inheritance and the cyclical nature of it means that generational trauma is one of the most devastating results of racism and colonialism present today.

In class, we learned about genocide and the devastating effects on individuals who have lived through genocides of their people, along with the effects that this is bound to have in their lives after survival. The Holocaust was a recent infamous example of this and the way it has shaped the Jewish population throughout the world is profound. Another form of genocide that has more recently been accepted is cultural genocide, which, according to the European University Institute, is “the systematic destruction of traditions, values, language, and other elements that make one group of people distinct from another” (Novic, 1970). Indigenous peoples across the world, and specifically in the Americas, have experienced both traditional genocide and cultural for centuries. Across generations, they have had to deal with the attempted erasure of their very selves, their culture, their traditions and what makes them a distinct race. The very fabric of their generational beings has been threatened and abused. Native Americans deal with psychological issues, including “depression, substance abuse, collective trauma exposure, interpersonal losses and unresolved grief and related problems within the lifespans and across generations, along with having higher health disparities than any other racial group in the United States (Brave Heart et. al, 2011, pg. 282). Substance abuse and suicide rates are also significantly higher among indigenous populations than any other, with the suicide rates being a shocking 50% higher than the national average (Brave Heart et. al, 2011, pg. 283). The effects of generational trauma, including forced assimilation and genocide, are more devastating and pertinent for this ethnic group than perhaps any others in the Americas.

(Image of Indigenous people from Bolivia https://southamericamission.org/donate/ministries/indigenous-rural-outreach/)

I think the profound trauma inflicted on indigenous groups is something that needs to get far more mainstream attention than I feel it does. Indigenous peoples are such a high-risk group that more programs and the like need to be directed toward them. They carry the weight of ancestors’ traumas that cannot truly be put into words. The burden must be astronomical, and the horrifying part is that it’s not over. This isn’t simply past trauma that they must cope with, but ongoing. Ideally, I would like to see more scholarly work done on the topic in the future and particularly, on South American indigenous populations. Throughout my preliminary search on the topic, it quickly became clear that there is far less material available and beneficial infrastructure for South American indigenous population as compared to their North American counterparts.

References:

Brave Heart, M. Y., Chase, J., Elkins, J., & Altschul, D. B. (2011). Historical trauma among indigenous peoples of the americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.628913

Novic, E. (1970, January 1). The concept of cultural genocide : An international law perspective. Cadmus Home. https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/43864

Adolescent Trauma-Informed Care

Trauma-Informed Care is a vital tool to use in helping individuals cope with trauma, especially adolescents. Here is an infographic to visually share some key aspects of trauma-informed care when working with adolescents.

Unpacking Psychopathy

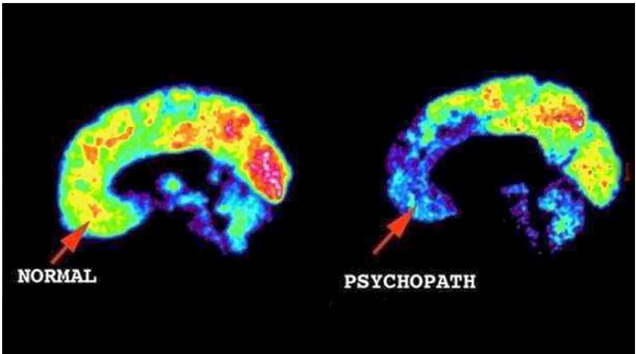

Psychopathy is a disorder that has encapsulated the minds of societies around the world. You may be wondering, what makes psychopathy so interesting? Depending on who you ask you will probably get a different answer. Some people believe that it is because they are able to tap into the egos that most people would rather and probably chose to stay hidden. Looking back at the research done by Sigmund Freud on psychoanalytical theory, he postulated that the mind is composed of three elements: The Id, Ego and Super-Ego. An average person’s Ego “ensures that the impulses of the id can be expressed in a manner acceptable in the real world” (Cherry, 2020). Part of what makes psychopathy interesting is that, the parts of the brain that are responsible for emotions such as empathy, guilt, fear and anxiety are still present but reduced. With advancements in technology we now have the ability to scan people’s brains (as seen below in the image by Dr. James Fallon) and take a more introspective glimpse into what the minds of people. A study done the University of Wisconsins School of Medicine shows that “both structural and functional differences in the brains of people diagnosed with psychopath and those two structures in the brain, which are believed to regulate emotion and social behavior, seem to not be communicating as they should” (Koenigs, 2017). This study opens so many doors for researchers from all different disciplines to explore psychopathy. It is important for psychopathy to be explore by numerous disciplines because not only it is imperative that we know the medical side of psychopathy because it allows us to view this disorder from multiple angles. Including different disciplines such as education and psychology into the world of psychopathy allows a more effective and ethical approach to psychopathy. Another essential disciple is education, which is vital because it allows it allows us to learn what causes psychopathy, who may be more susceptible too and knowing these things can be substantial in reducing a problem before a larger one arises.

I think another large part of what makes people so fascinated by psychopathy is that on the outside they are just like anybody else, they have an ability to turn on and off their charm and their cunningness. They walk, talk and dress like us which allows them to blend into the rest of society. Characteristics such as charm and cunningness often lead to them being attractive to others and being able to advance in the world. They know how to get what they want and they are smart and know how to manipulate others. The idea of having a so-called “hidden personality” is what makes people so interested in psychopathy. Also, the idea that we may not even know someone is a psychopath, they could be standing right next to us, a friend, a family member or really anybody. This has transcended into them being popular topics in media, film, television, writing and more.

Sources:

Fallon, J. (2005). Control v. james fallon’s brain. CNN: UC Irvine. accessed 16 April 2022.

https://www.cnn.com/videos/bestoftv/2014/05/28/erin-intv-fallon-inside-the-mind-of-a-young-killer.cnn

University of Wisconsin-Madison: School of Medicine. (2017). Psychopath’s brain show differences in structure and function.

https://www.med.wisc.edu/news-and-events/2011/november/psychopaths-brains-differences-structure-function/#:~:text=The%20study%20showed%20that%20psychopaths,of%20brain%20images%20were%20collected.

Cherry, K. (2020). Freud’s id, ego and superego. Very Well Minded.

https://www.verywellmind.com/the-id-ego-and-superego-2795951

Erasing the mental health stigma for law enforcement

Therapy is often seen as taboo, especially in certain job fields. Police officers are perhaps one of the most important groups that should be seeking support, but the stigma surrounding therapy stops them. Many departments, however, are trying to defeat this stigma. In Washington D.C., a grant of $7 million dollars was created. The Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act would be used for access to better mental health care for law enforcement (Justice Department Announces Funding to Promote Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness, 2021). The funding would allow training, demonstration projects, new practices related to peer mentoring, mental health, wellness, and sucicide prevention programs (2021).

This isn’t the first act, and it definitely won’t be the last act, that aims to provide mental health resources to law enforcement. The more acts/grants that are created, the more the stigma around mental health will be erased for this field and others. Law enforcement professionals have hard jobs. They handle danger, pressure, and the responsibility of protecting the public. This alone creates a lot of stress on them. The global pandemic had only increased the amount of stress and worry on officers, nurses, etc. Now more than ever, we as a society should be focused on promoting mental health, not stigmatizing it in a negative way. Seeking therapy should be no different than going to the doctor for an illness. We need to be mentally healthy just as much as we do physically, especially when carrying out a job like police officers do.

Sources:

Justice Department Announces Funding to Promote Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness (2021, October 14). In Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-funding-promote-law-enforcement-mental-health-and-wellness

Person-Centered, Trauma Informed Care for Holocaust Survivors

All “Holocaust survivors have endured trauma” according to Kavod, a journal dedicated to survivors (2018). Results of their trauma are physical, neurological, psychological, social, and cultural impacts. Physical impacts include, but are not limited to poor dental care and diabetes, and if the Holocaust survivor lived in the Former Soviet Union near Chernobyl, they faced all kinds of problems due to the radiation (benign tumors, heart disease, pulmonary disease, etc.). Neurological impacts include Dementia and Alzheimers. Psychological impacts include, but are not limited to hoarding (afraid of not having enough because they had nothing during the war), PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Social impacts include, but are not limited to trust issues, 2nd and 3rd generation intergenerational trauma, living below the poverty line, etc.. And the cultural impacts of the trauma mostly have an effect on religion. Some Holocaust survivors become culturally religious because they feel as though God have saved them, while others become anti-religious because they question “why did God allow this tragedy to happen?” With all of these impacts of their trauma in-mind, the Jewish Federations of North America (JFNA) knew that Holocaust survivors needed more than regular trauma-informed care. So in 2015, JFNA came up with Person-Centered Trauma-Informed Care (PCTI) that would address all the needs of survivors that are not just limited to therapy. PCTI is a “holistic approach to providing services. It would promote dignity, strength, and empowerment of trauma victims by incorporating knowledge about trauma in victims’ lives into agency programs, policies and procedures” (ACL 2021). In addition to therapy, other services will be provided that focus on mental, cognitive, and physical health, education and training to caregivers and people who will routinely interact with the survivor, socialization with support groups, and support for families of survivors and their caregivers. JFNA awarded over 80 plus sub-grants to nonprofit organizations like Jewish Family & Children Services. The goals and services of the program include: “reduce social isolation among survivors; improve the physical, emotional, mental, and cognitive health of survivors; increase survivors’ access to supportive, legal, and financial services; and train and educate professional staff, family caregivers, and volunteers about caring for survivors in a PCTI way” (Kavod 2018).

Person-Centered Trauma-Informed Care is unique in the sense that all services are catered toward the patient, meaning that no treatment plan or interaction is the same. The environment will adjust in accordance to the patient’s needs and their triggers. Services are meant to be given in a safe, non-threatening, and non-traumatizing manner. Yesterday, I was able to interview a social worker from Jewish Children & Family Services who offered me an example of how the environment adjusted to her client. One of her clients, a Holocaust survivor, was a widower who had trouble sharing his story and had a lot of anxiety coming into the office. She asked him, “what makes you relaxed before going to bed?” He described that listening to classical music and dancing relieved his anxiety. So for every meeting with him, she would play classical music when he walked in and danced in the room for 5 minutes with the door open. Once that idea had occurred, the following session he was able to share his story. In a typical therapy session, it is unusual to do this, but in PCTI, everything is based on the individual’s comfort in their environment and the people they surround. Jewish Children & Family Services also train staff, volunteers, caregivers, and family members how to interact with the survivor and how to recognize signs of post-traumatic stress. In one year of the program, 98% of trained participants of PCTI felt that “they can now identify potentially traumatizing situations that may impact survivors” while 94% felt that “they are competent in creating a trauma-informed environment for Holocaust survivors” (Kavod 2018).

Overall, the recently established PCTI care program has been proven effective, and according to the social worker I had interviewed, she sees a great deal of improvement in her patients, many of whom turn their trauma into a positive thing by sharing their stories to others.

Works Cited

Person-centered, trauma-informed service. ACL Administration for Community Living. (2021, November 8). Retrieved from https://acl.gov/programs/strengthening-aging-and-disability-networks/advancing-care-holocaust-survivors-older

Teaching about trauma: Models for training service providers in person-centered, trauma-informed care. Kavod. (2018, February 27). Retrieved from http://kavod.claimscon.org/2018/02/teaching-about-trauma-models-for-training-service-providers-in-person-centered-trauma-informed-care/