Home

Community Trauma

As this course, along with the rest of the courses for this term close to an end, I’m often thinking about how my courses relate to each other and the real world. One thing that I have been left thinking of is trauma, and how traumatic events affect the community. In one of my other courses, I am looking at aggravated assault incidents, drug related crimes and poverty within a city. Looking at all of this data has left me wondering how communities that are constantly experiencing traumatic events cope, or if they just view it as their new normal. Communities who experience traumatic events once, whether that be neighborhoods that are experiencing an act of violence such as a homicide, or on the larger scale such as the events of 9/11 or the Boston Marathon, seem to be shocked to their core after the events that have happened, and these are usually broadcasted all throughout the media. What about communities who constantly, or on a more continuous basis, experience trauma? Do they build their own subculture around this trauma, and have it become their new normal? Or is it still traumatic every time an event happens, even though they happen frequently?

If you look at this on an individual basis, everyone reacts to trauma differently. With constant exposure to traumatic events, some people continue to view these events as traumatic, while others become desensitized to them. When looking at the community level, how do we support them as a whole? If a whole community is desensitized from all of the trauma they have experienced, how do we treat that at the community level, especially if that is the only normal that the community has ever known? Some responses to this might be to maybe open a neighborhood center where the kids within the community have somewhere to go, or to work on lowering the crime rates in the area.

Going Hand in Hand: Homelessness and Trauma

The subject of trauma is one that can have a significant impact on an individual no matter what point or chapter they are at in their life. Whether a person is living their best life in a LA penthouse, traveling the world and visiting Europe, or sitting on the corner of a street begging for spare change or a bottle of water- we all experience trauma on a daily basis. Homelessness is defined under several factors of having no place to call home- thus resulting in being on the streets seeking assistance from others. Many people feel trapped once they are out on the streets, as it is considered a chronic stressor that cannot be escaped due to a lack of motivation and assistance (Rousseau, 2023). There is a negative stigma brought along with this, as many individuals think that homelessness is a result from drug abuse, not searching hard enough to find a job, overwhelming financial burdens, or simply doing it to themselves and not caring about their future. This is in fact not accurate for every individual, as we see this with veterans struggling to find an income when back from war, a traumatic event that left them in a state of shock, losing or getting fired from a job, and much more. Being homeless in itself is more than traumatizing, and advocating for more awareness and opportunities to reduce the rate of people sleeping on streets under cardboard boxes is something that should be prioritized.

The first step of implementing more programs and resources starts with individuals grouping together and brainstorming ideas in which we would see a positive difference in the percentage of homeless people. Homeless shelters are a great place to bring in additional help from volunteers, psychiatrists, and therapists. There tends to be a common variable of PTSD in homeless people- in which this goes along with anxiety and depression from how impactful their trauma was (Rousseau, 2023). We see an example of this with a case study spotlighting “Ms. Harris”, a “middle-aged woman with a history of PTSD and alcohol use disorders who is currently receiving substance use treatment at a local homeless shelter” (Williams, 2022). With an extremely challenging time growing up, along with a rough adulthood and getting divorced, which resulted in a big loss of financial savings, she had nowhere to turn to besides a medical unit for treatment because she was not helping herself in any shape or form. Like herself, “some studies show the prevalence of alcohol dependence of homeless patients to be upwards of 55%, and similar rates of drug dependency” (Williams, 2022). She had gotten prescribed for PTSD and her alcohol use disorder, and as time goes on there has been a remarkable change in her life due to having all these resources at the shelter. Psychiatrists who have the opportunity to be that one person for these struggling individuals is not only rewarding for both of them, but allows outsiders in society to see that these programs are worth it and are beneficial to whoever utilizes them.

Ways in which there has been improvement in the mental health and trauma concentration for homeless people can be shown throughout multiple examples in society. Focusing on trauma and how an individual can perform their daily routine while coping with it is important, especially when trying to get back on your feet and find a place to work/live. The Treatment for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness helps those who are homeless and struggling with mental and substance abuse disorders, as the “goal of the program is to increase access to evidence-based treatment services, peer support, services that support recovery, and connections to permanent housing” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023). The program excelled so much in helping individuals that the SAMHSA announced 31 awards with the total contributions adding up to $15.8 million dollars (SAMHSA, 2023). Another rewarding program was the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, founded in 2001 with a “network of more than 150 centers nationwide” (Van der Kolk, 2014). The different projects were placed in shelters, group housing units, juvenile justice systems, correctional facilities, and any place where an individual might be fighting trauma on a daily basis on top of the hardships stemming from homelessness. The constant use and dedication of these two programs alone has made such an impact on homeless people and their constant trauma, making for a brighter future and a place to call home.

References:

Rousseau, D. (2023). Trauma and Crisis Intervention. Module 1. Introduction to Trauma. Metropolitan College Boston University.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2023, December 5). Homelessness Programs and Resources. SAMHSA. https://www.samhsa.gov/homelessness-programs-resources

Van Der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Williams, J. (2022, September 1). “I have no one”: Understanding homelessness and trauma. Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/i-have-no-one-understanding-homelessness-and-trauma

Bounce Back Program

Children can suffer severe psychological distress when they have experienced adversity, and it is crucial that we make programming to treat child PTSD. To begin treating child PTSD in school settings, “Bounce Back” was created by the UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior (Blueprints, 2023). The “Bounce Back” Program is a cognitive-behavioral group intervention meant to assist in relieving symptoms of childhood PTSD, anxiety, depression, and functional impairment for elementary school children ages 5-11 (CEBC, 2015). The program serves children who are affected by community, family, or school violence, natural disasters, or traumatic separation from a loved one due to death, incarceration, deportation, or child welfare detainment (CEBC, 2015).

The goals of Bounce Back are to reduce symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety, build skills to enhance resilience to stress, enhance students coping and problem-solving strategies, impact students’ academic performance by improving their attendance and ability to concentrate, and build peer and caregiver support (CEBC, 2015). The program is made up of 10 one-hour group sessions, three individual sessions, and one to three parent education sessions over the course of three months. Group sessions are held during school hours and focus on topics like relaxation training, cognitive restructuring, social problem solving, positive activities, trauma focused intervention strategies, emotional regulation and coping skills (Blueprints, 2023). Many of the topics are tailored for the age group that receives them, utilizing storybooks, and games in engagement activities.

The outcomes of the program were very positive, with the Bounce Back program posttest treatment yielding results of significantly improved PTSD symptoms (parent and child reported), anxiety symptoms (child reported), emotion regulation (parent reported), and emotional and behavioral problems (parent reported) (Blueprints, 2023).

Cited limitations for the initial study were a small sample size, lack of control group at three month follow up, and length of follow up (CEBC, 2015). Something that could be added to this program is assessment of ACE scores for the children who are receiving treatment, to identify what kind of care plan they may need. High ACE scores leave children more at risk for PTSD and other conditions, so it may be beneficial to assess risk by administering the ACE test to the elementary school participants. However, from a round table view, “Bounce Back” could be what school systems need to treat childhood trauma and support at risk students who face adversity.

References:

Blueprints. (2023). Bounce Back. Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. https://www.blueprintsprograms.org/programs/1074999999/bounce-back/

CEBC. (2015). Bounce Back. CEBC " Bounce Back ’ Program ’ Detailed. https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/bounce-back/detailed#:~:text=Bounce%20Back%20directly%20provides%20services,attendance%20and%20inability%20to%20concentrate

The Trauma of Incarceration

One of the readings I found to be most interesting this semester was The Trauma of the Incarceration Experience as it discusses a topic I had previously written about in my documentary review. This reading describes the trauma inmates face in the prison system. With over 10 million individuals being incarcerated at any given time world wide, the rates of traumatic experiences and mental health issues that prisoners face are quite high (Piper & Berle, 2019, pg. 1). It is common for people who have been incarcerated to describe unimaginable violence and horrors that they have witnessed during their time in jail. Both DeVaux and Browder described witnessing violence, and both had experiences where defending themselves from violence led to them facing solitary confinement. These experiences that inmates face can lead to things such as PTSD, as an article from 2019 found that “Research examining PTSD in incarcerated populations reported estimates at a staggering 48%, compared to lifetime prevalence rates of 8.7% in the general US population” (Piper & Berle, 2019, pg. 2). These rates emphasize the need for trauma informed care in the carceral system in the United States. Providing trauma informed care to people who are incarcerated could be incredibly beneficial to their mental health, and decreasing recidivism rates.

For the documentary review I watched Time: The Kalief Browder Story. It’s a documentary about Kalief Browder who was 16 years old when he was falsely accused and arrested for stealing a backpack. He was sent to Rikers Island where he was frequently beaten and put in solitary confinement for a majority of the 3 years he spent in jail. He struggled immensely after being released due to the trauma he faced while being incarcerated, and at the age of 22 he committed suicide. His story highlighted the trauma inmates face in prison, and this article also describes a first hand experience of trauma in the carceral system. A quote that I found incredibly important from The Trauma of the Incarceration Experience was that “The experience of being locked in a cage has a psychological effect upon everyone made to endure it. No one leaves unscarred.” (DeVaux, 2013). Kalief also described the impact that incarceration has on everyone that faces it, and the lack of support given to him while he was incarcerated during his as an activist. This article by DeVaux explains how “people in prison may be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorders, as well as other psychiatric disorders, such as panic attacks, depression, and paranoia; subsequently, these prisoners find social adjustment and social integration difficult upon release” (DeVaux, 2013). Prison can cause long lasting mental health issues, and oftentimes these issues are not treated while in prison, making the adjustment back into the community more difficult.

During Browders time at Rikers Island, he experienced a severe mental health decline, and despite begging prison officials for help and treatment, his pleas were ignored. Despite the fact that treatment for him could have been life saving, he was denied help multiple times, causing his suffering to worsen. Kalief spent 700 days in solitary confinement, which accelerated the rapid decline of his mental health. According to Chadick et al, those in solitary confinement “typically spend 22–24 hrs of isolation with approximately 1 hr allotted for exercise or shower each day; some facilities only allow shower time three to 4 days a week” (Chadick et al, 2018, pg. 2). As social creatures, this isolation can have severely detrimental impacts on inmates and their mental health. A study from 2001 looking at the impact that solitary confinement (SC) has on mental health found that the “Incidence of psychiatric disorders developed in the prison was significantly higher in SC prisoners (28%) than in non-SC prisoners (15%). Most disorders were adjustment disorders, with depressive disorders coming next” (Anderson et al., 2001). They found stress to be a major contributing factor, which oftentimes prisoners in solitary confinement experience extreme levels of stress in isolation. Chadick et. al stated that prisoners in solitary confinement often “experience a myriad of mental health concerns and symptoms, including appetite and sleep disturbance, anxiety (including panic), depression and hopelessness, irritability, anger and rage, lethargy, psychosis, cognitive rumination, cognitive impairment, social withdrawal, and suicidal ideation and self-injurious behaviours” (Chadick et al, 2018, pg. 2). Implementing trauma informed care in our prison systems could be beneficial because “ all staff can play a major role in minimizing triggers, stabilizing offenders, reducing critical incidents, de-escalating situations, and avoiding restraint, seclusion or other measures that may repeat aspects of past abuse” as the prison setting is full triggers that could be impacting the mental health of inmates (Miller & Najavits, 2012).

Kalief also described post-release how difficult it was for him to adjust and integrate back into society. He was enrolled in college before his passing, but it was something he really struggled to adjust to due to the trauma that he faced. With trauma-informed care and better support during his transition from jail back into the community, Kalief could have had the support he needed in order to adjust smoothly and thrive post release. He struggled for the remainder of his life due to the trauma and lack of support he faced during his time in jail, but spent the remaining time after his release advocating for better treatment of those who are incarcerated. The trauma that both of these men faced during their time in jail is something that impacted them for the rest of their lives. I had watched the Kalief Browder documentary when it first came out in 2016, and it was just as impactful to watch now as it was the first time I saw it. Devaux’s experience in the system is incredibly similar to Browder’s, and unfortunately many others have had similar experiences. Kalief described the same paranoia that Devaux had, and both also described witnessing and experiencing unimaginable violence. Kalief’s story was one of the first times I had realized the trauma inmates face in the system, and this article gave me an even better insight and understanding as to how the carceral system facilitates traumatic environments for inmates.

Resources:

Andersen, H. S., Sestoft, D., Lillebaek, T., Gabrielsen, G., Hemmingsen, R., & Kramp, P. (2000). A longitudinal study of prisoners on remand: psychiatric prevalence, incidence and psychopathology in solitary vs. non-solitary confinement. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102(1), 19–25.https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.10200

Chadick, C. D., Batastini, A. B., Levulis, S. J., & Morgan, R. D. (2018). The psychological impact of solitary: A longitudinal comparison of general population and long‐term administratively segregated male inmates. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 23(2), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12125

DeVeaux, M. (2013). The trauma of the incarceration experience. Harvard Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Law Review, 48

Miller, N. A., & Najavits, L. M. (2012). Creating trauma- informed correctional care: a balance of goals and environment. European journal of psychotraumatology, 3, 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17246. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17246

The Importance of Self-Care for Law Enforcement Officers

Matthew S. Paradis

It is no secret that law enforcement officers are repeatedly exposed to stress and trauma throughout their careers. The cumulative stress and/or PTSD can wreak havoc on the overall health of an officer, especially if left unmanaged. Police officers generally experience higher rates of depression, PTSD, burnout, and anxiety when compared to the general population (NAMI). They also commit suicide 54% more than the general population (Violanti, 2020). This number is exacerbated when considering small departments, as this rate increases to over three times the national average” (NAMI).

There are many contributing factors to these statistics and yet despite knowing the statistics, the underlying problems persist. Police officers are tasked with solving or addressing many societal problems and yet they are hesitant to address their own. Barriers exist that discourage or prevent officers from seeking out help, even if they recognize that they are having difficulties with PTSD or some form of mental illness. More importantly, there is a stigma surrounding officers and emotional and/or psychiatric conditions, such as fear of losing their job, having their ability to carry a firearm taken away, reassignment to a less “stressful” position, and being labeled as weak and eliciting ridicule, humiliation, and retaliation from fellow officers or administration (Rousseau, Module 6).

In light of the ominous statistics previously discussed, there are viable options to help address the underlying issues at hand, mainly in the form of self-care. While officers are hesitant to seek assistance, exercising various forms of self-care can be incredibly beneficial to an officer’s overall health and well-being. Simplistically, officers should do their best to get adequate sleep, exercise regularly, eat well, do their best to relax, and connect with those who they have meaningful relationships with, particularly significant others. These areas need to be prioritized by officers who wish to continue to enjoy their lives and their careers rather than just going through the motions. These things must be done with purpose and in doing so, officers may find themselves in a better position to serve others to the best of their ability.

When the oxygen masks come down in an airplane during an in-flight emergency, flight attendants advised passengers to take care of themselves first before taking care of others. This same principle holds true with police officers prioritizing their own health (Cordico). Whether it be yoga or some other type of physical exercise, practicing mindfulness, journaling, finding a hobby, speaking with a mental health professional or peer support, or some combination of these strategies or others, police officers need to champion their own health and in doing so, they will be better suited and equipped to effective manage what the job will throw at them and be in a position to serve their families and communities to their best of their abilities. Self-care can provide a sense of personal control in an otherwise chaotic world, allowing us to pursue meaningful endeavors and engage in healthy lifestyle choices, supporting personal growth and furthering our resilience to the stress and trauma inherent in policing (Rousseau, Module 1).

Greco, N. (2022, March 4). The importance of self-care for law enforcement. Cordico. https://www.cordico.com/2021/05/21/take-care-of-yourself-why-law-enforcement-officers-need-self-care/

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2023). Law enforcement. NAMI. https://www.nami.org/Advocacy/Crisis-Intervention/Law-Enforcement

Rousseau, D. (2023). Module 1 - Introduction to Trauma. MET CJ720. Boston University.

Rousseau, D. (2023). Module 6 – Trauma and the Criminal Justice System. MET CJ720. Boston University.

Violanti JM, Steege A. Law enforcement worker suicide: an updated national assessment. Policing. 2021;44(1):18-31. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2019-0157. Epub 2020 Oct 21. PMID: 33883970; PMCID: PMC8056254.

Can Playing Dungeons & Dragons Be a Trauma Treatment Tool That Bridges the Victim-Offender Overlap?

It’s close to midnight when your party enters the roadside inn half a mile outside of the town of Waterdeep. You’re a rogue and thief wanted for murder, so you conceal your face. While your friends make their way over to the bar, you slink into a booth in the darkest corner of the dining room. As you note all the possible exits in the building, a waitress meets your gaze and begins to make her way over to where you are sitting. Before she can get close, two strangers block her path and start speaking to her in hushed but insistent tones. You succeed in rolling a perception check. The waitress seems extremely distressed, and you hear her say, “I said ‘no,’ now leave me alone.”

You’re a rogue and a thief. It would be best if you didn’t make a scene, but your character sheet also says that part of your background is that your family abused you, and you vowed never to let an innocent person be hurt by someone else. Your friends are distracted at the bar and don’t see the woman who needs help. It’s up to you. You roll a successful intimidation check and put a hand on the shoulder of one of the aggressors. “She asked you to leave,” you say. Thankfully, the strangers leave the inn, only looking a little annoyed. “Thank you,” the waitress says, stopping short when she sees you more clearly. Recognition flashes across her face. “It’s you!” Well, here it comes, you think. Off to jail, again. “Everyone, everyone!” she says, “It’s The Savior of Baldur’s Gate! Get this hero a drink!!” Oh yeah, you remember, I guess we did save that city a few sessions ago. Word travels fast.

~

In the first discussion post for this course, I was instantly drawn to van der Kolk’s (2015, p. 17) observation about imagination: “Imagination is absolutely critical to the quality of our lives [and] it is the essential launchpad for making our hopes come true.” From victims of child abuse using sand to play and act out narratives that they may not remember the words for (Rousseau, 2023b, p. 16) to veterans of war struggling to see peaceful images in inkblots (van der Kolk, 2015, p.16) to offenders of horrific crimes having to live with the trauma of institutionalization on top of learning to live a crime-free life (Rousseau, 2023c, p. 15), imagination is the most essential tool to build resilience in environments where inspiration is in short supply.

While the story I wrote above might seem goofy to you as the reader, I believe that as the player, and as your own main character, the choices you make and the actions you take can be exhilarating, and important at the very least. This is why I think we love knowing a little bit about our star sign, and why we take all those surveys that tell us which character of whatever TV show we would be. This can be a fun reverie for anyone, if, of course, your horoscope says you’re going to win the lottery and you’re most like the protagonist, hot girl, cool guy, etc. For people who may avoid their past or find that they are unable to leave their past behind them, I believe games, like trauma-informed Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), can be used to practice imagination, act as a complex form of talk, group, and exposure therapy, and instill a long-lasting resilience in people who have experienced many different forms of trauma and chronic stress.

If you’re unfamiliar with D&D, this is a great synopsis of the game, written by Blakinger (2023), who interviewed inmates on death row who used the game to cope with their death sentences: “[D&D is a] tabletop role-playing game known for its miniature figurines and 20-sided dice. It combines a choose-your-own-adventure structure with group performance[.] Participants create their own characters — often magical creatures like elves and wizards — to go on quests in fantasy worlds. A narrator and referee, known as the Dungeon Master, guides players through each twist and turn of the plot [with] an element of chance.”

Before you discount me completely, remember that playing games that improve our “physical, mental, emotional, and social resilience” can add years to our lives (McGonigal, 2012; Rousseau, 2023a, p. 8) and individuals who have experienced trauma and chronic stress may already have had the physical effects of stress take years off their life (Rousseau, 2023a, p. 4). Rousseau (2023a, p. 4) lists “uncertainty, loss of control, and a lack of information” as factors that trigger stress. It is unrealistic to imagine a future in which none of these factors occur, but the human body’s response to stress (van der Kolk, 2015) calls for treatment in safe spaces where we can learn how to deal with this natural response to past trauma. With every roll of the dice, the success of your decisions in this game is left completely to chance, but the player is always in control of what they decide to do and how they respond to successes and failures. While there is a lack of information, the Dungeon Master knows everything about this fantasy world. There are boundless opportunities to learn, explore, and discover the unknown.

In addition to the safe space that this game creates as a practice zone to cope with stress and possibly even face one’s fears, I believe that D&D can also be used as a tool for reclaiming positive narratives and labels, particularly for offenders. Labeling theory states that “people become stabilized in criminal roles when they are labeled as criminals” (Cullen et al., 2022, p. 7). A tool known as “redemption scripts” (Cullen et al., 2022, p. 248-250) has been used in efforts for people to discover their “true selves” or the best parts of them that could be the foundation for a crime-free life. I believe with guidance from a therapist or other trained mental health professional, the character creation portion of this game, which often takes place one-on-one and before the roleplaying part of the game, could be beneficial to offenders seeking a personal label change.

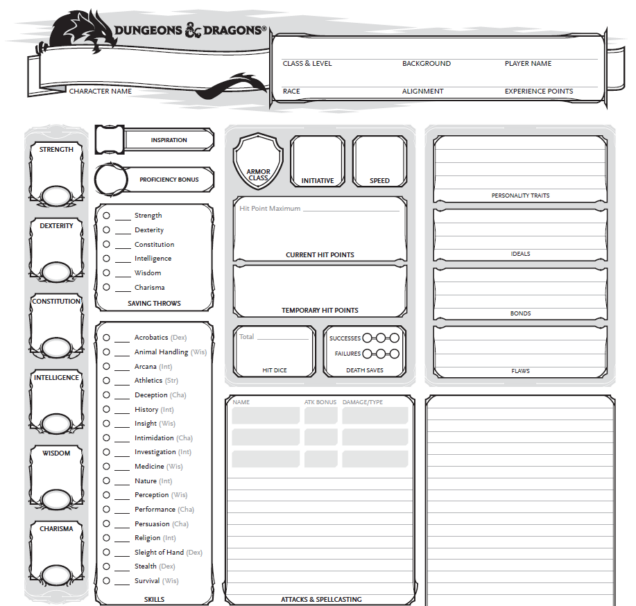

While this is just a brief exploration of this idea, it would be very interesting to see how resilient trauma-impacted individuals both inside and outside of prisons were after just a few sessions of playing D&D, and if they thought about their fantasy adventures outside of the sessions at all, and in what way. If you’ve never played D&D, I understand it might be confusing to think about how powerful this game can be. But, before you go, please look at the picture below. This is a D&D character sheet. It’s what you fill out for the character you play during the game. This is where you list your character’s strengths, weaknesses, background, personality, and if you’re inherently good, bad, or just straight chaotic. If you have a moment, read the categories on the sheet, and think about two things: 1. What would this sheet look like if I were the character in the story? Particularly, what would the four categories on the righthand column say? And 2. If I could be anyone, my true self, what would it say then?

Thank you very much for keeping an open mind, maybe learning more about something new, and considering my perspective!

(D&D Blank Character Sheet, 2023).

References

Blakinger, K. (2023, August 31). When Wizards and Orcs Came to Death Row. The Marshall Project. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://www.themarshallproject.org/2023/08/31/dungeons-and-dragons-texas-death-row-tdcj

Cullen, F. T., Agnew, R., & Wilcox, P. (2022). Criminological theory: Past to present (7th ed.). Oxford University Press.

D&D Blank Character Sheet [PDF]. (2023). Wizards of the Coast. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://dnd.wizards.com/resources/character-sheets

McGonigal, J. (2012, June). The game that can give you 10 extra years of life. TEDGlobal 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://www.ted.com/talks/jane_mcgonigal_the_game_that_can_give_you_10_extra_years_of_life

Rousseau, D. (2023a). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 1. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from Blackboard [url].

Rousseau, D. (2023b). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 2. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from Blackboard [url].

Rousseau, D. (2023c). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 6. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from Blackboard [url].

van der Kolk, B. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, And Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

Student Athletes & Self-Care

For my blog post, I want to focus on self-care tactics specific to student athletes. While we've explored the topic of self-care more broadly in this course (with specific emphasis on criminal justice professionals), being a full-time college student, I want to explore the burden on student athletes as that is a much closer population group to me and my friends. Self-care for student athletes is crucial for maintaining physical, mental, and emotional well-being while managing the demands of both academics and sports.

While speaking to my friends, they highlighted a few self-care strategies they implement in their own lives. Among these strategies is ensuring proper nutrition for peak athletic performance. They note that athletes should focus on a well-rounded diet that includes carbohydrates, proteins, healthy fats, vitamins, and minerals. When available, meal planning and consulting with a school-appointed nutritionist can help ensure they get the right balance they need. Additionally, another recurring theme in my conversations with the college athletes was the need for adequate rest and sleep. Quality sleep is vital for recovery and overall health. The Children’s Hospital of Colorado notes that athletes should aim for 9-10 hours of continuous sleep per night to support muscle repair, mental focus, and overall well-being (Children’s Hospital Colorado).

However, in my exploration of this topic, the athletes I spoke to noted several barriers to maintaining good mental health. These barriers included time constraints due to busy schedules, lack of support regarding their social lives, and limited access to healthy food. In my additional research, I found this was a recurring theme in regards to the self-care of student athletes more generally. One such study I found noted that collegiate athletes often feel pressure to prioritize their athletic performance over their health, which could lead to neglect of important self-care practices (Rensburg, 2014). Another study found that the student-athletes who asked for mental-health support experienced stigma surrounding mental health issues in more ways than one, including a lack of understanding and/or support from coaches and teammates, and a general perception that seeking help for mental health issues was a sign of weakness. Many participants reported feeling pressure to hide or ignore their struggles with mental health, which often worsened their symptoms and made them feel isolated. However, when student-athletes did receive the support and understanding needed, they reported feeling empowered and more willing to seek help in the future (Marques & Martins, 2018).

Moving forward, I would love to see a world where the fullness of student athletes' mental well-being is considered. Similar to the issues faced by criminal justice professionals, for student athletes to perform at the highest level they are capable of, they need intensive support systems and strong self-care strategies. In the future, I hope this includes strategies not only to strengthen them as athletes and students but also as people.

References

Children’s Hospital Colorado. (n.d.). How Does Sleep Impact Athletic Performance?. Sleep for Student Athletes. https://www.childrenscolorado.org/conditions-and-advice/sports-articles/sports-safety/sleep-student-athletes-performance/#:~:text=Nine%20to%2010%20hours%20of%20continuous%20sleep%20helps%20with%20muscle,split%2Dsecond%20decision%2Dmaking.

Marques, L., & Martins, O. (2018). Scholarworks.edu. Exploring Mental Health Needs of Student Athletes. https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/rr172364v

Rensburg, C. (2014). Researchgate.net. Exploring wellness practices and barriers: A qualitative study of university student-athletes. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272458815_Exploring_wellness_practices_and_barriers_A_qualitative_study_of_university_student-athletes

Navigating the Healing Path: Unveiling the Intricacies of Trauma

In the realm of understanding trauma, Bessel Van Der Kolk's groundbreaking work in "The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma" has become a guiding light for those seeking to fathom the profound complexities of trauma and its impact on the human experience. As we delve into Part Three: The Mind's of Children, this insightful masterpiece, the journey into the interconnected realms of brain, mind, and body unveils a roadmap for healing that challenges traditional perspectives.

The Importance of Brain Development:

Van Der Kolk's emphasis on the interconnectedness of the brain, mind, and body prompts a deeper exploration into the significance of brain development, as highlighted in our course readings. Neuroscience continues to unravel the mysteries of the brain, shedding light on the profound impact of trauma. The illustration on page 53 intricately details the interplay between brain regions, particularly emphasizing the pivotal role of the prefrontal cortex, aptly referred to as the timekeeper (Van Der Kolk, 2014). "The more neuroscience discovers about the brain, the more we begin to understand the impact of trauma,"(Dr. Rousseau, 2023). The prefrontal cortex, crucial for normal human development, acts as the guardian of emotional regulation, fear comprehension, and the delicate balance between hyperarousal and hypoarousal. Van Der Kolk's insights invite us to contemplate the implications of early trauma on the development of this critical brain region.

Early Trauma and the Prefrontal Cortex:

In a healthy individual, the prefrontal cortex matures fully around the age of 25, making adolescence a period of developing maturity and turbulence. However, severe trauma during formative years can disrupt this process, leading to a smaller volume or developmental issues within the prefrontal cortex (Van Der Kolk, 2014). This disruption manifests as hypersensitivity to stressors, an impaired ability to self-regulate emotions, and heightened levels of fear and anxiety. "Individuals who have experienced severe trauma may have a smaller volume of or developmental issues with the prefrontal cortex," (Dr. Rousseau, 2023). The consequences are profound. Trauma victims often find themselves in a perpetual "stress" mode, where the oldest part of the brain reacts, shutting off conscious thought and triggering instinctual responses of fight, flight, freeze, or hide. Understanding this physiological response is crucial in comprehending the challenges trauma survivors face in their journey toward healing.

Stages of Adolescent Development and Trauma:

Normal human development follows a systematic progression, with each stage building upon the last. However, trauma introduces disruptive elements, impacting factors vital for healthy development. Van Der Kolk's work encourages a nuanced exploration of the stages of adolescent development and how trauma can impede these processes. Trauma disrupts the expected sequence of milestones, creating a tumultuous environment that challenges the very foundations of growth "as it relates to child development, can take the form of very disruptive and often problematic harm," (Dr. Rousseau, 2023). For an example an infant must first learn to sit, then crawl, and finally walk, with each stage building essential skills for the next. However, trauma can skew this sequence, leading to delays or deviations in the expected progression. This misalignment has cascading effects on cognitive, emotional, and social development, hindering the acquisition of crucial skills necessary for navigating the complexities of adult life.

Understanding the intricate interplay between trauma and adolescent development is paramount for effective intervention strategies. Van Der Kolk's insights underscore the need for a holistic approach that addresses not only the immediate consequences of trauma but also the long-term implications on an individual's developmental trajectory. By recognizing the ways in which trauma disrupts the natural order of growth, we can tailor therapeutic interventions to foster resilience, restore developmental pathways, and empower survivors to reclaim agency over their narrative. In doing so, we inch closer to a trauma-informed paradigm that recognizes the unique challenges faced by individuals navigating the delicate terrain of adolescence in the aftermath of trauma.

As we navigate the intricate landscape of trauma with Bessel Van Der Kolk, the importance of understanding brain development, especially the role of the prefrontal cortex, becomes evident. Integrating these insights into our discourse on trauma allows for a more comprehensive and compassionate approach to healing. Van Der Kolk's work not only challenges our existing paradigms but also urges us to reevaluate and innovate in our quest to support survivors on their journey towards recovery.

References:

Rousseau, D. (2023). Trauma and Crisis Intervention. Module 2. Childhood Trauma. Metropolitan College Boston University.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Haitian Resilience, Natural Disasters & COVID-19

During the course, I read a piece by Guerda Nicolas about Haitians coping with the traumas associated with natural disasters and their resilience. Several post-disaster studies have found that there was notable prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression in the Haitian population. They have faced many political, economic, and environmental storms to include natural disasters (Nicolas et al, 2014, p. 93). Nicolas (2014) argues that the sociocultural traditions and customs of the Haitian people, family, religion, and community, are the reason for their resilience in the face of disaster.

Some refer to the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath as a “collective trauma,” defined as the “psychological response of an entire group to a traumatic event, such as the Holocaust” (Kaubisch et al, 2022, p. 28). From a psychological point of view, the threat of serious illness or death, the loss of jobs, the increased stress, the disruption in daily lives, the growing uncertainty, and the disconnect and isolation generated by the pandemic led to the consideration of COVID-19 as a traumatic event. Research suggests that one in five people could experience psychological distress post-COVID-19, such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Kaubisch et al, 2022, p. 27).

Prior to COVID-19, Haiti had just lifted restrictions from a political lockdown that had lasted almost a year and the country was also experiencing violent civil unrest triggered by an abrupt increase in fuel prices, a movement that became known as Peyi Lòk (Blanc et al, 2020). “When the first case of COVID-19 arrived in March 2020, the country was just beginning to regain a certain sense of normalcy despite the socio-economical and psychological ramifications of being on lockdown” (Blanc et al, 2020). Majority of the Haitian population continued to live their daily lives, as they were desensitized to the effects of disruption and forced isolation and distancing. Within three months, COVID-19 in Haiti had reached its peak and there was a decrease in the number of detected cases, predicting that the damage of the pandemic would not be too devastating to the country (Blanc et al, 2020).

It is argued that other countries, such as the United States, could learn from the Haitian experience of coping with traumatic events. Resilience is possible after exposure to trauma. Factors that promote posttraumatic growth are “positive social support, gratitude, strong family ties, attachment, and meaning making, or the way in which a person interprets or makes sense of life events” (Rousseau, 2023). The country of Haiti was created after the only successful slave insurrections in history and the resilience of that revolution threads through its history of tremendous struggles.

References:

Blanc, J., Louis, E.F., Joseph, J., Castor, C., & Jean-Louis, G. (2020). What the world could learn from the Haitian resilience while managing COVID-19. Psychological Trauma, 12(6), 569–571.

Kaubisch, L.T., Reck, C., von Tettenborn, A., & Woll, C.F. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic as a traumatic event and the associated psychological impact on families – A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 319, 27–39.

Nicolas, G., Schwartz, B., & Pierre, E. (2014). WEATHERING THE STORMS LIKE BAMBOO: The Strengths of Haitians in Coping with Natural Disasters.

Rousseau, D. (2023). Module 1: Introduction to Trauma. Blackboard.

Self-Care for Trauma Victims

People across the globe face traumas on a daily basis that leave long-lasting impacts. Some individuals rise above the occasion and overcome the travesties they’ve endured; however, some people are left not knowing how to properly cope. Trauma forever changes our brains. We face a devastating event, and our brains go into fight, flight, or freeze mode and some never leave those stages. This is where trauma and its negative consequences create problems in one’s day to day life. So, how do we move forward and past our traumas? How do we return to a state of homeostasis and mental stability to live a fulfilling life? Well, self-care is one of the most important practices one can utilize to help overcome their traumas.

Self-care is all about establishing practices to ensure one’s overall well-being, something trauma victims have difficulty achieving. There are many ways to accomplish this and there isn’t a “one size fits all” form of this. Many self-care practices are available as some work better than others depending on the person. Some common self-care methods are reading, taking a bath, watching your favorite TV show, spending time with friends and family, all things that would make you feel good (Hood, 2018). While important to remember to do things that make you happy, it is also important to remember to allow oneself to feel all emotions as they come (e.g., rage, sadness, defeat, grief).

One method of self-care found to be beneficial is journaling. Journaling allows oneself to express themselves and their emotions in a non-biased environment (van der Kolk, 2014). It creates a space for us to process our traumas and our feelings around it and further work through it. In fact, journaling has been shown to reduce rumination, the unhealthy practice of replaying painful events over and over again in your mind (LivingUpp, 2023). Using the pages of a journal give you a dumping ground for negative emotional energy creating some relief in the end. Journal also helps identify patterns; when you journal frequently about the same person, situation or worry, it clues us in to what need some further investigation (LivingUpp, 2023). This would further help us work through that specific problem area and move on with our healing.

Another helpful form of self-care is meditation. This is something we often see used in yoga, too. Meditation has been shown to not only calm someone, but also helps with anxiety and depression, cancer, chronic pain, asthma, heart disease and high blood pressure (Mental Health America, 2023). This self-care practice presents a state of peaceful mindfulness, allowing us to channel our energy into healthy lifestyle practices. This, again, is another tool that effectively allows trauma victims to work through their traumas and go on to live a happy and healthy life (van der Kolk, 2014). Meditation gives us the space to begin healing again.

Overall, there are several forms of self-care practices in which are effective and beneficial to those utilizing them. Those mentioned above just barely touch the surface. However, simple practices as those are a great way to begin the journey to healing. Trauma is a forever life-changing thing, and it takes a lot of work and time to heal from it. Starting the process with something as simple as reading your favorite book or treating yourself in another way, is just the beginning of the good to come when one practices self-care.

References

Hood, J. (2018, December 20). The importance of self-care after trauma. Highland Springs Clinic. https://highlandspringsclinic.org/the-importance-of-self-care-after-trauma/#:~:text=You%20can%20do%20this%20by,during%20the%20trauma%20healing%20process.

LivingUpp. (2023, December 10). Journaling as self-care. https://www.livingupp.com/blog/how-to-journal-for-self-care/#:~:text=Health%20Benefits%20of%20Journaling,-Journaling%20has%20many&text=Expressing%20your%20thoughts%2C%20fears%2C%20and,over%20again%20in%20your%20mind.

Mental Health America. (2023). Taking good care of yourself. https://mhanational.org/taking-good-care-yourself

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.