CJ 725 Forensic Behavior Analysis Blog

Institutional Betrayal Trauma and Peer Victimization

" [Institutional courage] is an institution’s commitment to seek the truth and engage in moral action, despite unpleasantness, risk, and short-term cost. It is a pledge to protect and care for those who depend on the institution. It is a compass oriented to the common good of individuals, the institution, and the world. It is a force that transforms institutions into more accountable, equitable, healthy places for everyone." - Center for Institutional Courage

Bullying as a form of aggressive behavior can elicit traumatic responses in many different populations. The most commonly addressed forms of bullying are school or childhood bullying and workplace peer victimization. Betrayal trauma theory addresses the traumas experienced by victims that are not always clinically recognized as traumatic. There are different types of betrayal trauma such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse committed by a caregiver, cultural betrayal, and institutional betrayal. Peer victimization, or bullying, can play a part in these experiences. Peer victimization on its own is exacerbated by institutional betrayal. Reports of peer victimization often go unaddressed by those in power at schools, and if they are addressed it is not usually an effective response. This ineffectiveness on account of the people and institutions that hold the power to address bullying poses as a form of institutional betrayal; thus leading to many victims of bullying to also experience a second form of trauma in institutional betrayal.

Both peer victimization and betrayal trauma are linked to post-traumatic stress reactions, but neither institutional betrayal nor peer victimization are officially listed in the criteria required for a clinical post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. This has opened up research that questions the clinical implications for people who experience traumas not listed in the PTSD criteria and possible solutions. Institutional betrayal exacerbates peer victimization which shares symptomatology with PTSD; it should be considered for either inclusion of the PTSD diagnosis or grouped with other forms of childhood betrayal trauma to form a new diagnosis.

Peer Victimization and PTSD

Peer victimization in children, commonly called “school bullying,” takes place during sensitive periods of development. PTSD symptoms are often reported in victims of bullying (Idsoe et al., 2012). Bullying is a highly interpersonal event and it is known that experiencing an interpersonal trauma is linked with significantly higher levels of PTSD symptoms compared to other kinds of trauma (Lancaster et al., 2009 as cited in Idsoe et al., 2012). The relationship was originally established in workplace peer victimization, but is branching out towards school bullying. This is important to note because school bullying takes place during adolescence, an important developmental period of biopsychosocial systems. This presumes that bullying may have an adverse effect on biopsychosocial development.

Among the post-traumatic stress symptoms reported by people who have experienced bullying is dissociation. Dissociation is a very common symptom of PTSD. Gušić and colleagues (2016) conducted a study about different types of trauma in adolescence and their relation to dissociation. They found that emotional traumas, like bullying, showed stronger associations with dissociative experiences (DEs). Girls reported both higher levels of DEs and bullying. Betrayal traumas are also a kind of emotional trauma, and research shows that women experience more betrayal traumas than men do (Freyd, 2020). These associations between peer victimization and PTSD argue that the incidents of bullying can lead to symptoms that meet the clinical threshold of distress, for peer victimization to be officially recognized as an inciting traumatic event.

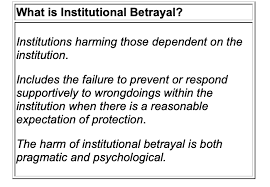

Institutional Betrayal

If peer victimization on its own results in post-traumatic stress symptoms and is perpetuated by academic institutions, then peer victimization is further complicated by institutional betrayal. Institutional betrayal is defined as transgressions perpetrated by an institution upon individuals dependent on that institution, including failure to prevent or respond supportively to transgressions by individuals committed within the context of the institution (Freyd, 2020). Institutional betrayal plays a part in peer victimization as most school bullying takes place in the context of the school by a peer also enrolled at that institution. This betrayal extends further into the institution when a victim’s disclosure is not responded to effectively.

There is relatively limited research on what characteristics define an adult’s response as “helpful or supportive” to an adolescent’s disclosure of bullying (Bjereld et al., 2019). First it is important to acknowledge that, yes, there are preventive and interventive strategies that produce positive outcomes. The problem is presented when school officials (assuming the victims’ parents have attempted effective communication, if they are aware of the bullying) fail to implement these strategic responses. These are similar to some of the responses that survivors of sexual assault receive, such as minimization or invalidation of the incident and a sense of abandonment when no steps are taken to address the issue once disclosed. Bjereld and colleagues’ (2019) study found that teachers often found a student’s disclosure as them misinterpreting the event or debated whether the victim was to blame. Once a student had disclosed and determined that the response was ineffective, they were less likely to report future incidents.

Clinical Implications

The clinical implications of peer victimization and institutional betrayal are apparent in that neither falls under the official PTSD Criterion A requirement. This may lead to multiple obstacles such as an onslaught of diagnoses that impede treatment, incorrect or incomplete treatment, and incorrect or incomplete diagnoses. One of the main uses of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) is for insurance purposes. This allows for affordable treatment, and official recognition and documentation of the outcome of a victim’s experience. Both of these are important in relation to receiving treatment, but also working on easing another betrayal trauma from healthcare institutions. Not being acknowledged by another set of officials who have the power to provide assistance can constitute another institutional betrayal.

Clinical implications may cascade into policy implications as well. Official documentation may also require the school to respond to an incident as effectively as possible, such as amendments to codes of conduct and disciplinary actions. This in turn could reduce the extent of institutional betrayal on a case by case basis, but also work toward resolving the root issue of peer victimization.

Diagnostic Solutions

There are multiple considerations in searching for possible solutions concerning an official diagnosis. There is debate about the limitations of the PTSD diagnosis, especially the constitution of Criterion A. Other commonly explored diagnostic solutions are complex PTSD and developmental trauma disorder (DTD).

Complex PTSD refers to the experience of survivors of prolonged and repeated traumas, and can consist of symptomatology that differs from PTSD (McDonald et al., 2014). While symptoms include the amplification of PTSD symptomatology, survivors of complex PTSD may also experience changes in relationships (i.e., fluctuations between healthy and unhealthy attachment and withdrawal). Bullying is defined as a kind of aggressive behavior involving repeated negative actions over time by a perpetrator against an individual who cannot defend themselves (i.e., a power imbalance) (Idsoe et al., 2012). This supports the notion that peer victimization is not only linked to the current PTSD diagnosis, but common reactions to peer victimization fulfill requirements for a new or revised PTSD criteria implementing consideration of complex PTSD.

DTD is a proposed clinical diagnosis that was previously considered but ultimately denied inclusion in the DSM-5. The American Psychiatric Association’s defense was that the idea that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) could lead to substantial developmental disruptions was more “clinical intuition” than evidence-based fact (van der Kolk, 2014). However, research has shown that ACEs, which include bullying, can have negative effects on brain development. Other research on ACEs have shown that distressing events can lead to symptoms similar to PTSD (Ossa et al., 2019). Previous targets of school bullying are at a higher risk for poor general health and have greater difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships.

In the DSM-5, there are specifications for children under six in the PTSD diagnosis. These include slightly different symptoms or presentation of PTSD symptoms. Van der Kolk (2014) writes that PTSD symptoms along with the specifications for early childhood trauma can be fully explained by a diagnosis of DTD. McDonald and colleagues (2014) conducted a study measuring potentially traumatic experiences (PTEs), and whether these experiences were predictive of a distinct set of symptoms characteristic of DTD. Bullying (physical, relational, verbal, and cyber) was included on the list of PTEs. Results confirmed a substantial amount of distressing life events that occur during childhood and adolescence. They also support future revision of the DSM-5 to include a developmentally-focused diagnosis for PTSD-like symptoms that do not necessarily meet PTSD Criterion A.

Conclusion

Institutional betrayals reach as far as one’s local schools. Peer victimization has been further impacted by institutional betrayal and is a national problem. Reports of peer victimization often go unaddressed, and if they are addressed it is not usually an effective response. This ineffectiveness on account of the people and institutions that hold the power to address bullying poses as a form of institutional betrayal. This leads to many victims of bullying to also experience a second form of trauma in institutional betrayal.

Both peer victimization and betrayal trauma are linked to post-traumatic stress reactions, but neither are officially listed in the criteria required for a clinical PTSD diagnosis. This has led research to explore the clinical implications for people who experience traumas not listed in the PTSD Criterion A requirement, and possible solutions. Possible solutions include three revisions of the DSM-5 to include at least one of the following: 1) a revision of PTSD Criterion A to include traumatic events not currently listed, 2) the addition of complex PTSD, or 3) the addition of a developmentally-focused diagnosis for post-traumatic stress reactions that do not fall under PTSD Criterion A.

References

Bjereld, Y., Daneback, K., & Mishna, F. (2019). Adults’ responses to bullying: The victimized youth’s perspectives. Research Papers in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1646793

Freyd, J. J. (2020). What is a betrayal trauma? What is betrayal trauma theory? Freyd Dynamics Lab. http://pages.uoregon.edu/dynamic/jjf/defineBT.html

Freyd, J. J., & Birrell, P. (2013). Blind to betrayal: Why we fool ourselves we aren’t being fooled. John Wiley & Sons.

Gordon, S. (2020, April 02). How bullying can lead to ptsd in kids. Very Well Family. https://www.verywellfamily.com/bullying-can-lead-to-ptsd-460614

Gušić, S., Cardeña, E., Bengtsson, H., & Søndergaard, H.P. (2016). Types of trauma in adolescence and their relation to dissociation: A mixed methods study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(5), 568–576. http://dx.doi.org/doi/10.1037/tra0000099

Herman, J. L. (1997). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence-from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Idsoe, T., Dyregrov, A., & Idsoe, C. E. (2012). Bullying and ptsd symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 901-911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9620-0

McDonald, M. K., Borntrager, C. F., & Rostad, W. (2014). Measuring trauma: Considerations for assessing complex and non-ptsd criterion a childhood trauma. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(2), 184-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.867577

Ossa, F. C., Pietrowsky, R., Berin, R., & Kaess, M. (2019). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among targets of school bullying. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(43). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-019-0304-1

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). Developmental trauma: The hidden epidemic. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

The Lone Child (Children at the Southwest Border)

The Lone Child

Fall of 1995, my two (2) brothers and I came to this country from the Dominican Republic with my late grandmother. I remember that day as if it was yesterday. Waking up bright and early, driving to the airport, and going inside that plane was exciting but scary. I remember my grandmother clenching my hand as the airplane took off from the runway and my ears popping as the airplane reached a higher elevation. Once we landed, I was amazed with the airport and size of the buildings around New York city. It was one of the best days of my life.

Unfortunately, not every child has had the same experience. The United States’ southwest border has seen a spike in families attempting to cross the border into the United States from South America. These families leave their homes, walk hundreds of miles, and even pay “coyotes” to smuggle them across the border. A “coyote” is an individual who works for an organization who are dedicated to smuggling humans across the border. These families risk everything they have and leave their homes in a pursuit of a better life. Unfortunately, after paying the coyote a quantity of money, the families are either defrauded or just dumped somewhere near the border to fend for themselves. These families are then forced to walk and go through dangerous situations that can cause negative lifelong effects on their children and themselves.

When crossing the border, families also risk being detained by Homeland Security agents guarding the border and risk having their children separated. Some children have been seen arriving to the border with no adult present. These children have been known to suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders, that affect their mental health in the long run. According to the American Psychological Association, “PTSD symptoms were significantly higher for children of detained and deported parents compared to citizen children who parents were either legal residents or undocumented without prior contact with immigration enforcement. (Nami,Martinez, 2021)” Further research shows that these children remain fearful that there will be another time where they are separated from their parents.

The detainment of migrant children and separation from their parents has caused heated debates amongst Americans. As mentioned above, the separation of a child from its parents can cause long lasting effects but how do we prove that these children belong to these individuals identifying themselves as the parents or guardians? Coyotes have also been known to sexually traffic juveniles into the United States for profit. Our society has seen many Human Trafficking cases coming from different countries and entering the United States. What do we need to do to better handle migrant children entering the country without a parent or guardian present?

(National Alliance Mental Illness, 2021)

(National Alliance Mental Illness, 2021)

As of now children who are separated from their parents are held at in holding facilities with other children. While in detention, Custom Border Protection agents determine if the child qualifies as an unaccompanied child. While waiting, these children can be placed into shelters, foster homes, group homes, etc.

While the government attempts to figure out what the child’s verdict should be, I believe we should invest into these holding facilities, group homes, foster homes, etc to make sure these children are receiving the care they need. Providing a good nutritional meal, exercise, living conditions, and education, can alleviate the PTSD or trauma a child may be dealing with. Providing video conference calls with families back home or in the United States can also assist in the process while they wait for the courts to proceed. We should further invest in counseling for these children who are held in these facilities. Attempting to figure out the problems and motivation for attempting to cross the border will help us understand how to help these families. Another way to help alleviate the stress and trauma in these children is to provide better funding for the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR).

The ORR is an organization where migrant children are sent to. Unfortunately, these facilities are separated and miles away from where the child’s parents might be being held. Providing funding for more southwest border locations will prevent children from being separated and keeping them closer. The farther away a child is from their parents, the better chance for that child to lose contact. Another way to alleviate the trauma is to transform these holding facilities into more welcoming, hospital like locations and not so much like a prison.

In conclusion, while I understand that migrants are attempting to enter the country at record breaking numbers, the United States must do their best to understand why these people are attempting to enter. Let’s provide better funding for the facilities near southwest border. Turn these facilities into hospitals and triage centers that better evaluate family relationships and the vetting process. Evaluating family relationships as fast as possible will prevent families from having to be broken up. This is an issue that is never going to stop, so instead of trying to stop it, let’s figure out a way to make it better and less harming.

References

Children are still being separated from their families at the border. Vera Institute of Justice. (n.d.). Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.vera.org/news/children-are-still-being-separated-from-their-families-at-the-border

Council on Foreign Relations. (n.d.). U.S. detention of child migrants. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/us-detention-child-migrants

Trauma in children of Latinx immigrants. NAMI. (n.d.). Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/February-2021/Trauma-in-Children-of-Latinx-Immigrants

Trauma…the good, the bad, and the ugly

What comes to mind when you hear the word “trauma”? Most often we associate it with negative feelings/emotions of pain, sadness, harm, and struggle. What if I told you that the trauma experiences that I have dealt with in life have enabled me to grow and learn about myself? I would like to talk about post traumatic growth. In my experience trauma can either disable you or motivate you. I experienced trauma as a child which had formed my outlook on life. Sometimes those habits are hard to break. However, it wasn’t until my adult trauma’s that I began to understand what makes Meredith tick. Trauma experiences as a child are not easy to process as children don’t have the knowledge and coping mechanisms that can be developed in adulthood.

In 2013, I traveled by commuter train to Boston to watch a friend run the Boston Marathon. I had run it the year before. I had taken up a “home base” at the Atlantic Fish Company on Boylston Street very near the finish line. In the passing time, I had unknowingly walked by both bombs within a very close time of them detonating. I had only been inside the restaurant for a minute or so when I heard the first bomb explode and felt the ground shake. My first inclination about what it may have been was maybe the catwalk or stands had collapsed at the finish line. That first explosion drew my attention out the plate glass window in the front of the restaurant and that is when I saw a flash and heard another explosion. Right then, from my training and experience, I knew they were bombs, and it was terrifying.

Through my fears, my training and experience as a State Trooper took hold. I immediately went into work mode and ushered people into the basement floors of the restaurant. People were streaming in from the street outside and were hysterical, I tried to provide them comfort. I subsequently exited the restaurant and saw a man with no leg. I assisted in grabbing tablecloths and ice from inside the restaurant, bringing them outside to aid the injured. I saw a man sitting over young Martin Richard. He looked at me and I looked at him and we knew he was dead. That picture is forever engrained in my mind. I then saw two men carrying his sister, toward an awaiting Rescue. The response to the tragedy was extremely fast as there were Rescue personnel already on standby at the finish line for runners. As a law enforcement officer, we call this “controlled chaos”. This controlled chaos are the situational conditions that we have been trained to handle. Rescues, doctor, nurses were right at the finish line to assist the finishing athletes, little did they know they would have a much different task that day.

Although I sought out therapy for what I experienced, I didn’t do enough work. I was back to work quickly to avoid watching the media attention, and subsequently dealing with the stressors of work on top of what I had experienced in Boston. A couple years later I found myself in an abusive relationship and it was during this time I can now see that I fell into a steep downward spiral. In 2017 I had to have shoulder surgery from a dislocated shoulder suffered while hiking in Vermont. I had been in Vermont at a program for first responders suffering from addiction/substance abuse. Yes, I had found solace in the bottom of a liquor bottle like many first responders. After surgery, I voluntarily admitted myself into a 30-day residential treatment program in Michigan for those suffering from addiction and co-occurring disorders. It was the best decision I have ever made. For those of you that have never experienced an inpatient treatment program, you are essentially cut off from the rest of the world. No cell phones, no internet, no television. Your immediate job is to address yourself while removing outside influences and stressors so that you can concentrate on yourself. Often throughout life, addressing our inner being is the last thing on a list of many things to do. Yet it is the most crucial thing for our overall wellbeing.

Post Traumatic Growth (PTG) can occur from any experience that challenges your core values and beliefs about the world: what you’re capable of, the nature of the world, the nature of others, and your philosophy about life. (HPRC, 2022) Studies have found that more than half of all trauma survivors report positive change—far more than report the much better-known post-traumatic stress disorder. (Rendon, J., 2015) Post-traumatic growth (PTG) is a theory that explains this kind of transformation following trauma. It was developed by psychologists Richard Tedeschi, PhD, and Lawrence Calhoun, PhD, in the mid-1990s, and holds that people who endure psychological struggle following adversity can often see positive growth afterward. (Collier, 2016)

People who have experienced trauma must decide whether that trauma will define them or control them. That decision is most often made unconsciously. I would argue that part of PTG is bringing that unconscious thought to conscious action. That decision is made based on the experience at the time and place that the individual occupies. The decision is often uncontrollable, until you figure out what makes you “tick”. Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and freedom. (Pattakos, A., Dundon, E., 2017) Tedeschi, the leading psychologist in PTG, stated, “we’ve learned that negative experiences can spur positive change, including a recognition of personal strength, the exploration of new possibilities, improved relationships, a greater appreciation for life, and spiritual growth. (Tedeschi, 2020)

In my experience, I have grown to learn more about myself in my 40’s then I have in my entire life. That is not to say that it didn’t take work. When you find yourself stuck and realize that it is time to take time for you, I can say it is a freeing experience. Like many others, I found it extremely difficult to say “no”. Learning to say “no” can be exhilarating. PTG is life changing. It’s important to understand and accept that our life experiences may influence our actions and beliefs, but they don’t need to control us. Having a clear mind to rationally attack life’s “bumps in the road” is necessary for this growth. In my experience, PTG has forced me to try new things, brought what is important into perspective, gave me a new perspective on things, allowed me to grow as a person, forced me out of my comfort zone, provided me with a new understanding on others experiencing trauma, and made me realize that I am human. Through PTG you begin to understand just what resilience is and how we can increase our tolerance of uncomfortable things. Resilience is a crucial protective factor in the individual that resists the influence of multiple risk factors. (Bartol & Bartol, pg. 37, 2021) Resilience defined is successful coping with or overcoming risk and adversity, the development of competence in the face of severe stress and hardship, and success in developmental tasks or meeting societal expectations. (McKnight & Loper, 2002, pg. 188)

Furthermore, we all need to learn to listen to our bodies. It is the first indication that something is amiss, and we all too often ignore the signs. Being able to detect even slight changes in our bodies can help us to recognize what we are experiencing and assist us in making better decisions. Learning through mindfulness to be present in the moment. It is imperative that we make time for ourselves, however small time that may be. It is crucial to our wellbeing.

Bartol, C., & Bartol, A. (2021). Criminal behavior: A Psychological Approach (12th ed.). Boston.

Collier, L. (2016, November). Growth after trauma. Monitor on Psychology. Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/11/growth-trauma

Human Performance Resources by CHAMP (HPRC), 5 benefits of post-traumatic growth. (2020, September 11). Retrieved August 11, 2022, from https://www.hprc-online.org/mental-fitness/mental-health/5-benefits-post-traumatic

McKnight, L.R., & Loper, A.B. (2002). The effect of risk and resilience factors on the prediction of delinquency in adolescent girls. School Psychology International, 23, 186-198.

Pattakos, A., & Dundon, E. (2017). Prisoners of our thoughts: Viktor Frankl's principles for discovering meaning in life and work. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Rendon, J. (2015, July 22). How trauma can change you-for the better. Time. Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://time.com/3967885/how-trauma-can-change-you-for-the-better/

Tedeschi, P. G. (2020, August 31). Growth after trauma. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://hbr.org/2020/07/growth-after-trauma

Transitional Shift in Criminal Justice Proceedings

Criminal justice and the study of deviant behaviors has seen many paradigms shifts since its inception. From the pseudo-science of phrenology to the cruelty of the Pennsylvania prison model, these non-evidence based approaches to criminal justice has brought tangible harm countless victims.

If we presuppose that the aim of criminal justice is to reduce the likelihood of offender recidivism then this premise will provide us with some indicia of how the current systems are performing. The adversarial model of criminal justice is widely accepted in western societies as both familiar and entrenched in tradition. In this model, criminal matters are deemed settled when the offender in question is assigned a specific punishment for their respective transgressions. (Maschi, 2014) Punishment is nearly universally limited to housing individual offenders within a prison facility based on their respective criminal offence and risk based demeanor. This punishment serves the dual purpose of incapacitating a specific offender for a determinate period of time and acting as a deterrent to the overall public. Administratively, this process of criminal justice is unaffected by the desires of the victims, it does not seek to make the community whole nor does it attempt to make the offender understand the deleterious nature of their action. The most damning condemnation of the adversarial model of criminal justice is that it fails to transform offenders into law-abiding citizens after their institutionalization. Statistically, once a prisoner has been released from an in custody facility there is an approximately 50 percent chance that they will be reconvicted of a criminal offence within 3 years. (Nagin et al., 2009) This data is relatively consistent over multiple countries that employ a western model of criminal justice. Within the United States, the issue of recidivism is further exacerbated by the mass incarceration rates, which shows that around 2.3 million Americans are in some form of custody. (Nagin et al., 2009)

As presently constructed, the adversarial model of criminal justice employed in the United States has undoubtedly failed in its raison d’etre. Based on the statistics mentioned above, we can extrapolate that the economic burdens along with the sheer concentration of human suffering produced far outweighs any actual benefits derived.

So where do we go from here? If we concede that rehabilitation is the central component to the process of obtaining justice, we have no alternatives but to evoke a radical paradigm shift towards a truly restorative justice model.

Restorative Justice Principles as imagined by early proponent Howard Zehr is based less in the procedure of jurisprudence and focuses more on the communal effects of crime. (Maschi, 2014) Victim Offender Mediation open up the pathway of healing for both parties involved in a crime. The victim who was wrong is allowed to speak their feelings and the offender is able to see how their actions affect the community as a whole. Contrary to popular opinion, this system of justice produced through a sentencing circle provides both accountability of offenders and can utilize punishment other than imprisonment. Evidence surrounding restorative justice system shows strong reduction in decreased recidivism and an increase compliance with other forms of restitution. (Maschi, 2014)

Critiques against transitioning to a Restorative Justice System can come from multiple approaches. Pragmatically, an overhaul of the current system is seen by many as unnecessary given the presence of the adversarial model. However, this argument is academically inadequate because it is rooted in a lack of understanding rather than conveying any tangible benefits of the current systems. As a scientific field, criminal justice should seek to continuously improve upon it systems based on evidence supported by new research. Furthermore, with shifts towards specialized courts for individuals of the following categories veterans, drugs and mental health patients we are seeing a natural progression towards restorative justice practice as a society.

Another common critique levied by advocates against restorative justice model is that this type of proceeding is suitable only for minor offences. However contrary to this belief, New Zealand operationalized restorative justice conferences for serious violent offenders with police diversion reserved for minor offences. (Morris, 2002) Research results demonstrates that in comparison with a control group of similar offenders a marked improvement is observed from the conventional criminal justice proceeding. (Morris, 2002)

Moving towards new systems of criminal justice can be daunting however, this alone should not be the reason progress is halted. There is an ethical imperative for practitioners and professionals to call for a reformation of the current criminal justice system towards an institutionally restorative model.

Work Cited

- Maschi, T., Leibowitz, G., & Mizus, L. (2014). Restorative Justice. In L. Cousins (Ed.). Encyclopedia for Human Services and Diversity (pp. 1142-1144). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Wenzel, M., Okimoto, T. G., Feather, N. T., & Platow, M. J. (2008). Retributive and restorative justice. Law and Human Behavior, 32(5), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-007-9116-6

- Nagin, D. S., Cullen, F. T., & Jonson, C. L. (2009). Imprisonment and reoffending. Crime and Justice, 38(1), 115–200. https://doi.org/10.1086/599202

- Morris, A. (2002). Critiquing the critics: A brief response to critics of restorative justice. British Journal of Criminology, 42(3), 596–615. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/42.3.596

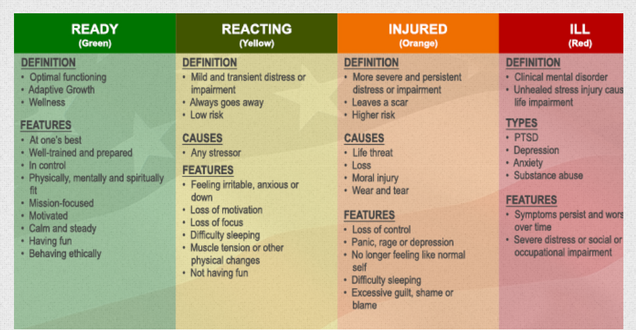

Self Care In the Criminal Justice Field: Pushing for Support

"Dark humor- it's just how we cope".

If you were to mention the topic of "self-care" to a room full of varying Criminal Justice professionals, chances are you will be laughed at. Immediately, and not necessarily openly, many would cite their coping skills and self-care methods as dark humor, drinking, and a lack of steady relationships and it would be welcomed and just considered to be part of the "norm". Self-care certainly has not been made a top priority in several areas of the Criminal Justice field such as within law enforcement, corrections, and even dispatch.

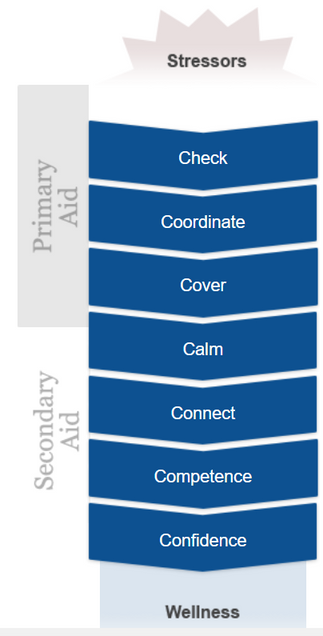

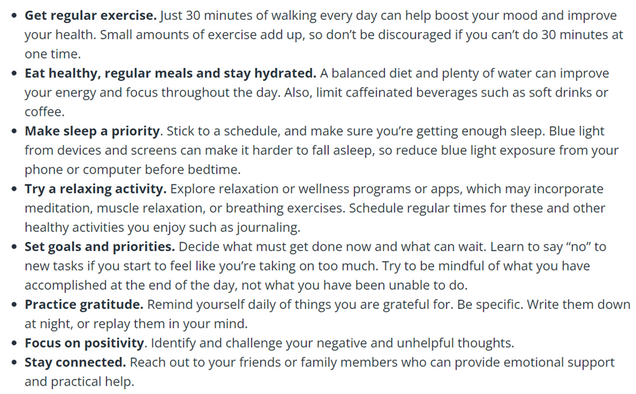

While this course has been aimed at better understanding forensic psychology, it has also given students the opportunity to take on and recognize the topic of self-care, hopefully instilling its importance in the long run. We know how deeply trauma can affect humans, and we often are taught to look for the signs in the people we work with. What isn't emphasized, however, is how to recognize the residual effects of the trauma we see and work within our lives. That is why self-care is so important! What is self-care, anyway? Well, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, self-care is "...taking the time to do things that help you live well and improve both your physical health and mental health" (NIMH, 2022). Some ways to achieve self-care include exercising, getting enough sleep, engaging in positive activities that promote deeper connections, and more. One of the biggest steps to self-care is recognizing the need for it and actively making the choice to pursue it! By making self-care and your mental health a priority, we hope to see less burnout and fewer people actively struggling, which then impacts their work, personal lives and so much more.

A FOCUS ON SELF CARE DOES NOT MAKE YOU WEAK.

Please see some of the below links for resources on mental health and self care.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Caring for your mental health. National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved August 14, 2022, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/caring-for-your-mental-health

https://www.everydayhealth.com/self-care/

https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/res-rech/p5.html

Megan Downing

Addressing the Victim to Offender Cycle

Throughout this semester in our class discussions, I have spoken in fragments about my experience working with child victims of sexual abuse. In one particular post, I spoke with another classmate about the unfortunate cycle of victim to perpetrator, which I would like to address later in this post. To first provide some background on my experience, a few summers ago I interned with my prosecutor's office special victims unit. As this was during the height of COVID, my responsibilities as an intern were unconventional. My primary responsibility was to help digitize old case files from previous years. As a result, I spent a lot of time handling files of cases from years prior. During this assignment, I came to the frightening realization of how commonplace these occurrences are. To that extent, my entire worldview began to shift when I realized I was in one county, of one city, of one state, of an unfathomably large world.

As a second responsibility, I was tasked with sitting in on victim interviews. To be more specific, while an SVU detective would interview a victim, I and one or two other staff would sit in another room that provided a live visual and auditory feed of the interview. I was charged with taking notes and documenting body language or subtle cues that the detective may have missed. As I sat in on these interviews and heard in real time these emotional and unsettling testimonies from children, a callous and apathetic outlook of offenders began to form.

I have often heard and echoed the notion that children, boys in particular, who are the victims of sexual assault, are now at a greater risk of committing the same act. Upon further research into the subject, I have learned that this sentiment actually does more harm than good to survivors of sexual abuse. The “victim to offender cycle” is complex and can not be simplified to such a degree. To understand the complexity and nuances of the cycle, we must review the research on sexual offending. First, the gender of the offender: males commit roughly 80% of offenses among boys and 96% of offenses among girls (2018). Second, risk factors of adults who have offended, these individuals tend to:

“Show greater aggression and violence, non-violent criminality, anger/hostility, substance abuse, paranoia/mistrust, and have diagnosable antisocial personality disorders… Be more likely to show anxiety, depression, low self-esteem… Generally have more problematic sexual patterns (including fantasies and sexualized coping strategies)... Have low social skills/competence… Have poorer histories of family functioning, including more harsh discipline, poorer attachment or bonding, and generally worse functioning of their family of origin, including physical abuse, and sexual abuse…” (2018).

The reality is, there are many factors at play regarding sexual offending. Significantly, research suggests that most men who have committed an offense were not sexually abused previously. Therefore, an important distinction must be emphasized between “risk” and “causation” — for those who are at a “higher risk” for later offending does not mean their victimization will be the one and only “cause”. A study in the UK that examined future offending in boys who were sexually abused found that 88% did not go until commit any sexual offenses (2018).

The streamlined ideology of “victims are now likely to be offenders later in life” is ubiquitous in our society. This creates a stigma for survivors. If you are the victim of abuse, in speaking about your experience, you may also be labeled as “someone who is likely to offend”. As a result, a victim might refrain from disclosing their abuse due to the fear of being viewed as a potential offender (2018). This ideology can also generate thoughts and feelings in survivors of being “contaminated” or the “vampire effect”. Specifically, boys and young men may feel the need to be hyper-vigilant of their own thoughts or feelings for fear that they may become “possessed” (2018). Besides being victimized, this dread of later offending has interpersonal ramifications such as “developing intimate relationships, marrying, having children, becoming fully involved in parenting, bathing or changing the nappy of their children, playing with or coming into contact with children, from relaxing, and from trusting in themselves” (2018).

As I mentioned previously, I too have contributed to this misconception. Unfortunately, it is a widely uncontested and accepted notion. However, the propagation of this idea does harm to actual survivors. This idea continues to persist because of its simple form factor. Unfortunately, it is easier to tolerate and believe this idea rather than the fact that we live in a world where people make the intentional decision to sexually abuse a child.

References

Addressing the victim to offender cycle. Living Well. (2018, February 13). Retrieved August 14, 2022, from https://livingwell.org.au/managing-difficulties/addressing-the-victim-to-offender-cycle/

Inherent Racism in Lack of Preventative Programming for At-Risk Youth

“It Is Easier to Build Strong Children than to Repair Broken Men” – Frederick Douglass

The seeds of crime are sown long before the first dollar is stolen, drug is sold or life is taken. Risk factors such as poverty, peer rejection, antisocial peers, inadequate after-school care and poor academic performance – not mention abusive or neglectful parenting and psychological maladies – can set a child on a course to antisocial and/or criminal behavior. The combination of multiple risk factors working together further compounds the probability; the developmental cascade model helps illustrate just how the interaction of negative and often traumatic experiences carve out a trajectory to crime by strengthening, influencing or informing subsequent skills and deficits (Bartol & Bartol, 2017). Sadly, children across the country are wrestling with plural risk factors every day. A national sample of children recently found that nearly 40 percent of children in American had been direct victims of multiple violent acts (2020b), one in five students report being subjected to bullying (2020a) and 11.6 million children just two years ago were found to have been living in poverty (2021). That is a lot of children with a lot of risk factors. And that is the bad news.

The good news, however, is that protective factors can create a metaphorical U-turn in this pathway, providing positive intermediaries for the negative conditions. One such factor is early childhood education. Quality education has been proven to reduce the likelihood of future criminal behavior, with children in satisfactory schools exhibiting no more behavior issues at age eight than those with college-educated mothers (2018). The Perry Project is one such program, an educational intervention first established as a study examining the effects of high-quality preschool on at-risk children and their communities. Based on the HighScope strengths-based learning approach, the analysis concluded that by age 40, low-income children who attended competent preschool programs enjoyed greater financial earnings, had greater potential for employment, experienced less criminal involvement and were more likely to have completed high school (2004). Conversely, research on government-funded Child-Parent Centers in Chicago found children excluded from the program 70% more apt to be arrested on charges of violent crime by age 18 and five times more likely to experience chronic crime-involvement by adulthood (2018).

This buffering effect of early education on children with developmental risk factors is widely accepted, roughly nine out of ten police chiefs agreeing that expanding quality childcare programs would significantly reduce crime (2018). Additionally, Sanford Newman, president of anti-crime organization Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, stated, “Law enforcement leaders know that to win the war on crime, we need to be as willing to guarantee our kids space in a pre-kindergarten program as we are to guarantee a criminal a prison cell” (2004). And as Joe Biden’s $775 billion child and elder care plan proposes universal preschool for three-and four-year-olds (2020d), things should be looking up for both children and the criminal justice system.

But there is a catch. A report by the Education Trust shows only one percent of Latino and four percent of Black children in 26 U.S. states are enrolled in “high quality” state-funded early learning programs (Ujifusa, 2019), blaming accessibility and affordability for the imbalance. The problem, it argues, is that states with better programming fail to reach their BIPOC children, and other states with higher percentages of children of color provide relatively lower-quality services. Meanwhile, nationwide statistics show that 30 states sustain a significant imbalance between enrollment of white children versus lower percentages of Latino children, and 18 states wherein white children are enrolled significantly higher than Black children (Hardy & Huber, 2020). The disparity is exacerbated by the fact that peer enrollment often has an impact on participation of other children (Hardy & Huber, 2020), so barriers to some can often mean barriers to many.

The question remains: why are adequate early learning resources less available to marginalized communities? Author Linda Darling-Hammond explains that it is a common fallacy that children of color and/or from disadvantage simply do not have the capacity to make good use of education (Darling-Hammond, 2001); from as long ago as the 1960s, Black children were viewed as socially, culturally and financially bereft, and, thus, in need of “fixing” (Allen, 2021). So affordable, accessible preschool for the BIPOC community has not gotten the funding nor attention it so desperately needs. And the very reason these resources remain sparse is the same reason why they are so needed; the Education Trust concluded in its report, “Systemic racism causes opportunity gaps for black and Latino children that begin early—even prenatally, which makes it crucial for these families to have access to high-quality [early childhood education] opportunities as a pathway to success into their K-12 education” (Ujifusa, 2019).

The need is becoming increasingly more urgent. As of last year, Black children were more than four times as likely to be held in juvenile facilities than their white counterparts (Rovner, 2021) and Latino youth 28 percent more likely (Bagley, 2021), even though adequate early education could help reduce this inequity and give children of color the possibility of success they have deserved all along. Naysayers argue that the cost of investment is simply too high, a familiar fallback excuse to continue inaction. But according to the Justice Policy Institute, incarcerating a single youth currently costs $588 per day, or $214,620 per year (2020c), whereas quality prekindergarten would virtually pay for itself by 2050 by yielding $8.90 in benefits for every dollar invested, $304.7 billion in benefits in total (Lynch & Vaghul, 2015). While these numbers may be overwhelming (to digest, not to mention decipher), the key point is this: quality, government-funded early childhood education would ultimately pay its taxpayers back in total, and the societal boon would manifest in reduction of crime, less incarceration and more citizens contributing to the welfare and economy of their communities.

The arguments are sound, the numbers add up, but racism rarely hears more than a dog whistle. It is up to those in the criminal justice field to implement these changes to give youth – and the adults they will become – a chance to thrive.

References:

Allen, R., Shapland, D. L., Neitzel, J., & Iruka, I. U. (2021). Viewpoint. creating anti-racist early childhood spaces. NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/summer2021/viewpoint-anti-racist-spaces

Bagley, N. (2021, July 23). Latinx disparities in youth incarceration. Youth Today. https://youthtoday.org/2021/07/latinx-disparities-in-youth-incarceration/

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2017). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach (Eleventh). Pearson.

Bullying statistics. PACER Center - Champions for Children with Disabilities. (2020, November). https://www.pacer.org/bullying/info/stats.asp

Children exposed to violence. Office of Justice Programs. (2020, January 8). https://www.ojp.gov/program/programs/cev

Darling-Hammond, L. (2001). Inequality in teaching and schooling: How opportunity is rationed to students of color in america. In B.D. Smedley, A.Y. Stith, L. Colburn & C.H. Evans (Eds.), The right thing to do, the smart thing to do (pp. 208-366). National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223633/ Doi: 10.17226/10186

Hardy, E., & Huber, R. (2020, January 15). Neighborhood preschool enrollment patterns by Race/ethnicity. diversitydatakids.org. https://www.diversitydatakids.org/research-library/data-visualization/neighborhood-preschool-enrollment-patterns-raceethnicity

Highscope Perry Preschool study. HighScope. (2004, November). https://highscope.org/highscope-perry-preschool-study/

The link between early childhood education and crime and violence reduction. Economic Opportunity Institute. (2018, October 17). https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/early-learning/ELCLinkCrimeReduction-Jul02.pdf

Lynch, R., & Vaghul, K. (2015, December 2). The benefits and costs of investing in early childhood education. Equitable Growth. https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/the-benefits-and-costs-of-investing-in-early-childhood-education/?longform=true

New Child Poverty data illustrate the powerful impact of America's safety net programs. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2021, September 20). https://www.aecf.org/blog/new-child-poverty-data-illustrates-the-powerful-impact-of-americas-safety-net-programs

Rovner, J. (2021, July 15). Black disparities in youth incarceration. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/black-disparities-youth-incarceration/

Sticker shock 2020: The cost of youth incarceration. Justice Policy Institute. (2020, July 30). https://justicepolicy.org/research/policy-brief-2020-sticker-shock-the-cost-of-youth-incarceration/

Ujifusa, A. (2019, November 6). Kids of color often shut out of high-quality state preschool, research says. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/kids-of-color-often-shut-out-of-high-quality-state-preschool-research-says/2019/11

USAFacts. (2020, October 16). Pre-primary enrollment statistics among three- and four-year olds. USAFacts. https://usafacts.org/articles/how-many-children-attend-preschool-us/

Testimony From a Child

The Sixth Amendment is the constitutional right for all offenders within the United States to be afforded the right to a trial with very specific requirements. Specifically, an offender has the right for a public trial without delay, the right to a lawyer, the right to face your accusers, and the right to an impartial jury. A portion of the rights afforded for a fair trial are having a witnesses testify as to the facts of the case, but what happens when the testimony is elicited from a child?

In the court of law, a subpoena holds the power to mandate any individual testify in situations that the court deems necessary. If a situation arises where the witness is a child, a subpoena can legally be used identically as if the witness were an adult. Respectively, “a parent who fails to bring a child to court after the child has been subpoenaed can be found to be in contempt of court, which can result in fines or even jail time” (Criminal Defense Lawyer). In this sense, serious concerns of responsibility arise when exposing children to the stressors of testimony in a courtroom, let alone recalling memories which are sensitive in nature that may induce trauma and horrific memories. Parents of these children have legitimate concern if their children become testifying witnesses which may hold weight in sentencing dangerous people. Witness intimidation, threats, or even violence is a serious issue when dealing with witness testimony in high profile cases.

In certain situations, “children can take the stand and testify in court, and the Judge has the ability to decide whether this is a good idea or not” (Rosen). Children can be called upon to testify in a multitude of situations. Often children are in the wrong place at the wrong time, viewing horrific incidents that their recollection is needed for. Homicides, vicious assaults, and car accidents resulting in death, are just a small list of criminal offenses that may be witness by a child. Most commonly, children are called to testify at divorce proceedings involving their own parents. The stress, anxiety, and trauma that is associated with taking the sides of your parents is a situation that no child should have to bear. Children of a young age are still mentally developing and are often unaware of the consequences of the words they are saying. It is understood “that infants and children differ in activity, emotionality, and general sensitivity to stimuli” (Module 1.3), thus creating varying and inconsistent reactions to depicted trauma. The testimony of a child can also be considered non-credible, considering their perception is that of an individual with no life experience or understanding of parental conflict.

The trauma of recalling sensitive events is authentic. Testifying in front of a large group of strangers, in a new and intimidating environment, about a topic that is disturbing in nature, is a recipe for trauma. Luckily, courts in certain states have enacted laws which have demonstrated sensitivity to these situations. Specific jurisdictions have allowed courtrooms to be closed to any audience members during the times of a child’s testimony. In some states, “child witnesses can also visit a courtroom before testifying to familiarize themselves with the surroundings and with court proceedings” (Criminal Defense Lawyer). Certain jurisdictions have even allowed testimony to be recorded to be played at a later date, further removing a child from in person testimony.

Ultimately, situations will arise where children are needed to testify. Legislation should be adopted which is accepted within all jurisdictions, prioritizing the potential trauma that is experienced by a child during testimony at court. Universal safeguards and protocols must be enacted which will be legally binding for all courts, prosecutors, and defense counsels to adhere to. Parents have the horribly difficult task with keeping their children safe, and unfortunately in the court of law, this protection can be ripped from them at a moments notice.

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 1: Thinking Like a Forensic Psychologist. Boston University Metropolitan College Forensic Behavioral Analysis. Blackboard.

Rosen Law Firm (2022) The Child’s Preference and Testimony in Court. Retrieved on August 8, 2022 from https://www.rosen.com/child-custody-course/childs-testimony-in-court/

Criminal Defense Lawyer (2022) Can A Judge Order My Child to Testify? Retrieved on August 9, 2022 from https://www.criminaldefenselawyer.com/resources/criminal-defense/juvenile/can-a-judge-order-my-child-testify-a-criminal-case

Waltrip Firm (2018 May 31) The Child Witness. Retrieved on August 9, 2022 from https://waltripfirm.com/child-witness-competency/

Times of Malta (2016 Oct 23) When Children Take the Witness Stand. Retrieved on August 9, 2022 from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/when-children-take-the-witness-stand-what-support-do-they-receive.628766

The Native American Children

LAWS MUST BE DEVELOPED FOR STATES

TO PUNISH

Sexual Abuse in the Native American Population

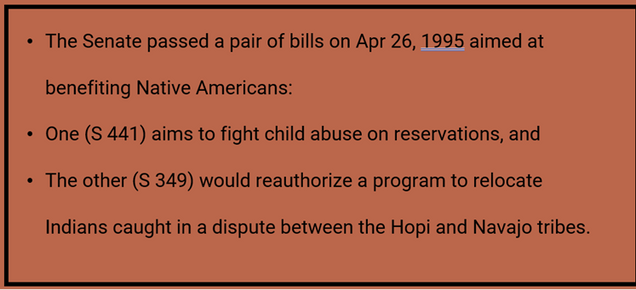

In 1786, the United States established its first Native American reservation and approached each tribe as an independent nation. This policy has remained intact for over one hundred years. Since the establishment of the reservations, State laws have been restricted to State territory. If there is a charge of sexual child abuse on a reservation, the State law enforcement cannot intervene.

Child sexual abuse is defined as an adult's use of a minor to satisfy sexual needs. Child sexual abuse is defined as a crime within State law. However, on Native American reservations, tribes create definitions within their own tribal codes to satisfy their community and law enforcement standards. It is also illegal for state authorities to enforce state laws on reservations. Most cases of child sexual abuse develop gradually over time, and the offender is known to the child in 90 percent of cases (Miller-Perrin & Perrin, 2007). According to the CDC defines obese kids as students who were greater than the 95th percentile for body mass index, based on sex-and-age specific reference data from the 2000 CDC growth charts (CDC.gov).

According to the CDC, the group that “Had Sexual Intercourse For The First Time Before Age 13 Years Among American Indian or Alaska Native Students United States, High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2019”

| Year % | Total % | Total Lower CI Limit | Total Upper CI Limit | Total N | Female % | Female Lower CI Limit | Female Upper CI Limit | Female N | Male % |

| 2019 | 4.7† | 1.5 | 13.9 | 109 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 54 | N/A |

| Male Lower CI Limit | Male Upper CI Limit | Male N |

| N/A | N/A | 55 |

The results were 109 students that were identified for this survey (CDC.gov). The confidence intervals for males these children were 1.5 to 13.9. These stats are not representative of the population. Mainly, this group is underrepresented because of the barriers to the reservations

The Deindividuation on Reservations

There are many theories that can be applied to this social issue. Here, Social Learning and Deindividuation are explored. Social Learning is a progressive advancement from classical and operant conditioning. Social Learning theorizes that human behavior is “based on learning from watching others in the social environment. On the reservations females and males alike learn than the sexual violation of little girls has a small risk value (Rousseau, 2022). Violators of children cannot be punished by state law enforcement officers. Reservation authorities are not usually contacted when a child sexual abuse occurs. Watching children being sexually abused without punishment, encourages others to repeat the same behavior (Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. 106). Deindividuation is the encouragement by others that a person is not present. Their anonymity can lead a factor of their victimization. A sexual predator can lose their identity and becomes part of the violating pack. This feeling generates a "loss of self-awareness, reduces concern over evaluations from others, and a narrowed focus of attention" (Baron & Byrne, 1977, as cited in Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. 120). When combined, these process may lead to the high rate of sex crime against children on the reservations.

Confirmed Maltreatment

The Impact Of Culture

- The article focuses on the impact of culture on the response of Native American parents to interventions concerning child abuse and neglect and child protection.

- It has been noticed that Native American parents react in a manner that cause childcare protection practitioners to view them as resistant and uncooperative.

Foster Care

- In some of the cases where the abused child is placed in foster care,

- it is not unusual for the parents to abandon their child and discontinue contact with the foster care agency.

A complicated legal arrangement

Out of the 574 American Indian Tribes in the U.S., only 200 are under the FBI's jurisdiction. This jurisdiction is a collaboration between the FBI and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Justice Services. "The federal government has a unique political and legal relationship with the 573 federally recognized tribes. The tribes are sovereign and have jurisdiction over their citizens and land, but the federal government has a treaty obligation to help protect the lives of tribal members" (FBI, 2022). This "trust responsibility," can be extended to give rights to children in the State that the incident occurs.

The array of Supreme Court decisions and federal laws that followed resulted in a complicated legal arrangement among federal, state and tribal jurisdictions, making it difficult for survivors of sexual assault to find justice.

You know the signs that you need to take better care of yourself when: You feel mentally or physically exhausted, overwhelmed or stretched too thin. Friends and family tell you you're working too hard, or have to remind you to take a break. You've worked 70- or 80-hour weeks.

Reference:

FBI, (2022). Indian Country. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/violent-crime/indian-country-crime

Pope, N. LMSW (2009) Miller-Perrin, C. L. & Perrin, R. D. (2007). Child maltreatment: An introduction, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 475 pp., Journal of Public Child Welfare, 3:1, 109-110, DOI: 10.1080/15548730802694918

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 1: Thinking Like A Forensic Psychologist. Boston University Metropolitan College Forensic Behavioral Analysis. Blackboard.

Stop Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is a significant global human rights issue, and sadly since human trafficking is covert, and since reporting is inconsistent, accurate data is scarce. People who are victims of human trafficking can be of any race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or nationality. Trafficking occurs to adults and minors across American communities, whether in the suburbs, rural areas, or urban areas. Various reasons may contribute to the victimization of these individuals, such as homelessness, runaway status, abuse, neglect, and a lack of safety at home due to violence. Millions of people across the globe are trafficked every year - including here in the United States (Department of Homeland Security, 2022).

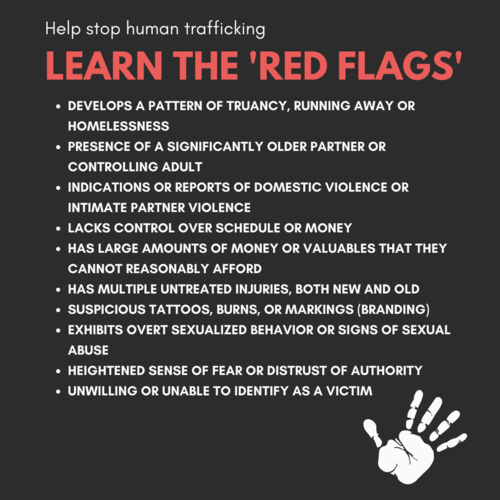

In the meantime, human trafficking is something that everyone is capable of discovering. There are many red flags and indicator signs that can help identify a human trafficking situation, such as; signs of physical abuse, poor living conditions, is the person fearful, timid, or submissive, does the individual appears to be coached on what to say, or does that person have freedom of movement (Department of Homeland Security, 2022). In light of this, there are numerous ways to support these victims of human trafficking once you have noticed these red flags and indicators. For instance, initiating a conversation in private, providing support and empowerment, listening to their comments and concerns, supporting their decisions, offering to help, and finally, if you believe that you have identified someone in the trafficking situation, alert law enforcement immediately (Supporting Victims of Human Trafficking-Valley Crisis Center, 2022). The National Human Trafficking Hotline is 1-888-373-7888, a 24-hour, toll-free, multilingual anti-trafficking hotline.

Nevertheless, there are simple ways to get involved and make a real difference: raise awareness of the issue on a local, regional, and national level, fundraise for anti-trafficking organizations, volunteer for anti-trafficking organizations, and promote anti-trafficking legislation (Public Service Degrees, 2020). The trauma suffered by survivors of human trafficking can often last a lifetime, both psychologically and physically. All anti-trafficking efforts should incorporate trauma-informed efforts to support survivors effectively, including the criminal justice system and victim services. When deploying prevention strategies and engaging with survivors, trauma-informed coping strategies and media reporting should also include a trauma-informed approach—getting trauma-informed means responding to the impacts of trauma on a person's life on a strengths-based approach. Human trafficking victims should be treated to minimize the likelihood of re-traumatizing them by recognizing signs of trauma and designing all interactions with them accordingly. To address survivors' unique experiences and needs, this solution focuses on creating a sense of physical, psychological, and emotional safety and well-being (US Department of State, 2021).

Sources:

Department of Homeland Security. (2022, April 13). What Is Human Trafficking? | Homeland Security. DHS. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/what-human-trafficking

Supporting Victims of Human Trafficking – Valley Crisis Center. (2022). Valley Crisis Center. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.valleycrisiscenter.org/supporting-victims-of-human-trafficking/

US Department of State. (2021, January 10). Identify and Assist a Trafficking Victim. United States Department of State. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.state.gov/identify-and-assist-a-trafficking-victim/

Public Service Degrees. (2020, August 14). Be the Change: How You Can Help End Human Trafficking. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.publicservicedegrees.org/403.shtml/