CJ 725 Forensic Behavior Analysis Blog

Adolescent Trauma-Informed Care

Trauma-Informed Care is a vital tool to use in helping individuals cope with trauma, especially adolescents. Here is an infographic to visually share some key aspects of trauma-informed care when working with adolescents.

Unpacking Psychopathy

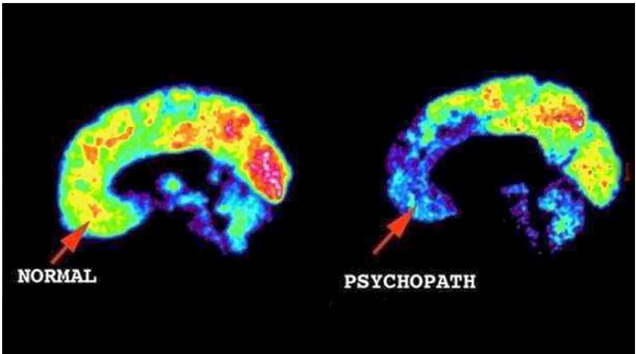

Psychopathy is a disorder that has encapsulated the minds of societies around the world. You may be wondering, what makes psychopathy so interesting? Depending on who you ask you will probably get a different answer. Some people believe that it is because they are able to tap into the egos that most people would rather and probably chose to stay hidden. Looking back at the research done by Sigmund Freud on psychoanalytical theory, he postulated that the mind is composed of three elements: The Id, Ego and Super-Ego. An average person’s Ego “ensures that the impulses of the id can be expressed in a manner acceptable in the real world” (Cherry, 2020). Part of what makes psychopathy interesting is that, the parts of the brain that are responsible for emotions such as empathy, guilt, fear and anxiety are still present but reduced. With advancements in technology we now have the ability to scan people’s brains (as seen below in the image by Dr. James Fallon) and take a more introspective glimpse into what the minds of people. A study done the University of Wisconsins School of Medicine shows that “both structural and functional differences in the brains of people diagnosed with psychopath and those two structures in the brain, which are believed to regulate emotion and social behavior, seem to not be communicating as they should” (Koenigs, 2017). This study opens so many doors for researchers from all different disciplines to explore psychopathy. It is important for psychopathy to be explore by numerous disciplines because not only it is imperative that we know the medical side of psychopathy because it allows us to view this disorder from multiple angles. Including different disciplines such as education and psychology into the world of psychopathy allows a more effective and ethical approach to psychopathy. Another essential disciple is education, which is vital because it allows it allows us to learn what causes psychopathy, who may be more susceptible too and knowing these things can be substantial in reducing a problem before a larger one arises.

I think another large part of what makes people so fascinated by psychopathy is that on the outside they are just like anybody else, they have an ability to turn on and off their charm and their cunningness. They walk, talk and dress like us which allows them to blend into the rest of society. Characteristics such as charm and cunningness often lead to them being attractive to others and being able to advance in the world. They know how to get what they want and they are smart and know how to manipulate others. The idea of having a so-called “hidden personality” is what makes people so interested in psychopathy. Also, the idea that we may not even know someone is a psychopath, they could be standing right next to us, a friend, a family member or really anybody. This has transcended into them being popular topics in media, film, television, writing and more.

Sources:

Fallon, J. (2005). Control v. james fallon’s brain. CNN: UC Irvine. accessed 16 April 2022.

https://www.cnn.com/videos/bestoftv/2014/05/28/erin-intv-fallon-inside-the-mind-of-a-young-killer.cnn

University of Wisconsin-Madison: School of Medicine. (2017). Psychopath’s brain show differences in structure and function.

https://www.med.wisc.edu/news-and-events/2011/november/psychopaths-brains-differences-structure-function/#:~:text=The%20study%20showed%20that%20psychopaths,of%20brain%20images%20were%20collected.

Cherry, K. (2020). Freud’s id, ego and superego. Very Well Minded.

https://www.verywellmind.com/the-id-ego-and-superego-2795951

Unpacking Psychopathology

Psychopathy is a disorder that has encapsulated the minds of societies around the world. You may be wondering, what makes psychopathy so interesting? Depending on who you ask you will probably get a different answer. Some people believe that it is because they are able to tap into the egos that a most of us would rather and chose to stay hidden. Looking back at the research done by Sigmund Freud on psychoanalytical theory, he postulated that the mind is composed of three elements. The Id, Ego and Super-Ego. An average person's Ego "ensures that the impulses of the id can be expressed in a manner acceptable in the real world" (Cherry, 2020). What makes psychopathy interesting is that psychopathy is that, the parts of the brain that are responsible for emotions such as empathy, guilt, fear and anxiety are still present but reduced. With advancements in technology we now have the ability to scan people's brains (as seen below in the image by Dr. James Fallon) and take a more introspective glimpse into what the minds of people. A study done the University of Wisconsins School of Medicine shows that "both structural and functional differences in the brains of people diagnosed with psychopath and those two structures in the brain, which are believed to regulate emotion and social behavior, seem to not be communicating as they should" (Koenigs, 2017). This study opens so many doors for researchers from all different disciplines to explore psychopathy. It is important for psychopathy to be explore by numerous disciplines because not only it is important to know the medical side of psychopathy because it allows us to view this disorder from multiple angles. Including different disciplines such as education and psychology into the world of psychopathy allows a more effective and ethical approach to psychopathy. Education is vital because it allows it allows us to learn what causes psychopathy, who may be more susceptible too and knowing these things can be substantial in reducing a problem before a larger one arises.

I think another large part of what makes people so fascinated by psychopathy is that on the outside they are just like anybody else, they have an ability to turn on and off their charm and their cunningness. These characteristics often lead to them being attractive to others and being able to advance in the world. They know how to get what they want, they are smart and know how to manipulate others. The idea of having a so-called "hidden personality" is what makes people so interested in psychopathy. Also, the idea that we may not even know someone is a psychopath, they could be standing right next to us, a friend, a family member or really anybody. This has transcended into them being popular topics in media, film, television, writing and more.

Sources:

Fallon, J. (2005). Control v. james fallon's brain. CNN: UC Irvine. accessed 16 April 2022.

https://www.cnn.com/videos/bestoftv/2014/05/28/erin-intv-fallon-inside-the-mind-of-a-young-killer.cnn

University of Wisconsin-Madison: School of Medicine. (2017). Psychopath's brain show differences in structure and function.

https://www.med.wisc.edu/news-and-events/2011/november/psychopaths-brains-differences-structure-function/#:~:text=The%20study%20showed%20that%20psychopaths,of%20brain%20images%20were%20collected.

Cherry, K. (2020). Freud's id, ego and superego. Very Well Minded.

https://www.verywellmind.com/the-id-ego-and-superego-2795951

Reducing Burnout: The Importance of Quality Self-Care

Everyday living in 2022 is stressful and balancing family, work, and free time is no easy task. In an economy with record high inflation rates, and a healthcare system burdened with the many implications of the pandemic, rest and recovery is of utmost importance now more than ever. With the US dollar having significantly less purchasing power than last year, many people are attempting to overcome this by working longer hours. More hours spent at work means less hours spent on other aspects of our lives that we value much more personally. The cognitive dissonance that a person experiences because of this work-life imbalance can lead to feelings of burnout.

Burnout is the central theme of an article published by the Harvard Business Review. Author Monique Valcour characterizes burnout by three symptoms: exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Exhaustion is described as profound physical, cognitive, and emotional fatigue and is the primary symptom of burnout. Cynicism is psychologically distancing oneself from one's work because of feelings of disengagement and lack of pride. Inefficacy is having feelings of incompetence and lack of achievement or productivity. If you have experienced a multitude of these symptoms then there’s a good chance you've experienced burnout.

So what can we do to address or prevent burnout? Valcour suggests making changes to some situational factors in our lives that could yield positive results. For example, we must be better at prioritizing self care. Valcour states, “It’s essential to replenish your physical and emotional energy, along with your capacity to focus, by prioritizing good sleep habits, nutrition, exercise, social connection, and practices that promote equanimity and well-being, like meditating, journaling, and enjoying nature.” In my opinion, this is the most effective, yet also most overlooked method for criminal justice professionals to take care of their physical and mental energy.

One of the main expectations of criminal justice professionals is to put others first before themselves. This mindset is vital in the line of duty, however it can be problematic when it trickles into our day to day lives. Law enforcement officers don’t have the option of taking it easy because they are sick or they are having a rough week. It’s highly stressful to work in situations where every move you make is scrutinized and one mistake could cost you your job or even worse, someone’s life. Research indicates that law enforcement is a particularly stressful occupation due to a number of sources from within the organizational structure itself, such as role ambiguity, role conflict, lack of supervisor support, lack of group cohesiveness, and lack of promotional opportunities (Anderson et al., 2002; Gaines and Jermier, 1983; Toch, 2002). So not only do officers have to deal with on-the-job stressors like exposure to violence and suffering, but they also have to deal with organizational stressors as well. That’s why it is imperative to leave as much of the stress at work as possible and practice good self care while off the clock.

It's necessary to delineate the differences between good self care and bad self care. Dietrich and Smith (1984) shed light on the nonmedical use of drugs and alcohol among police officers, “alcohol is not only used but very much accepted as a way of coping with the tensions and stresses of the day” (p. 304). Reducing the norm of officers turning to these maladaptive coping mechanisms is an important step in the right direction towards practicing better self care. Having worked as a first responder for several years now, I’ve experienced how stress has trickled into my daily life and how I manage my own self care through effective coping strategies. One way I do this is by leaving work at work. Some examples of how I manage to leave work at work are by muting my email while off-duty, not overanalyzing the decisions I made and what I could’ve done better, and using my time off whenever I physically or mentally need a break. I also value my health very seriously as this is another way I manage my own self care. I try my best to eat well, get adequate sleep, and exercise daily. Even when I don’t feel like lifting weights or running, I make sure I get out for at least a 30 minute walk. During this time I will usually throw on a podcast on a topic I am interested in learning about so I am essentially learning while exercising.

In summary, work burnout is a very serious and common problem for a lot of people, especially criminal justice professionals. In order to prevent burnout from occurring we must prioritize effective self care through healthy practices rather than maladaptive ones. Even though I’ve listed what I’ve found to be successful for myself, it's important to note that every individual is different so they must find what works best for them. After all, we all have different needs and there's no one particular strategy that universally works for everyone.

Anderson, G.S., Litzenberger, R. and Plecas, D. (2002). “Physical evidence of police officer stress”, Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 399-420.

Dietrich, J., & Smith, J. (1984). The nonmedical use of drugs including alcohol among police personnel: A critical literature review. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 14, pp. 306.

Gaines, J. and Jermier, J.M. (1983). “Emotional exhaustion in a high stress organization”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 26 No. 4, pp. 567-86.

Toch, H. (2002). Stress in Policing, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Valcour, M. (2016, November). 4 Steps to Beating Burnout. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/11/beating-burnout

Animals Help Us Heal

I have experienced significant trauma in my life. I didn't talk about it much when I was younger. I didn't want the attention. I don't want the attention now either. I talk about it now because it's part of who I am. I am a survivor who still tries every day to navigate her way through the jungle.

My pets have always been good for my mental health. Because of them, I am rarely lonely. The discipline of having to care for an animal keeps me moving forward, one step at a time. During times of intense stress, they calm me and focus me. These days I have two big dogs - Charlie and King. I couldn't be more grateful. The things I need, they need as well. They need to eat, go to the bathroom, and sleep. But, they also need to play. Today was a day without enough play. I am stressed and they can feel it. I will make it up to them tomorrow. I will allow myself time to play.

Halm, M. A. (2008). The healing power of the human-animal connection. American journal of critical care, 17(4), 373-376.

When Specialty Courts Fail

It is well documented that the United States incarcerates more of its population than any other developed country in the world. This fact alone has driven the need among criminal justice administrators and court systems to look at possible causes for the increase in incarceration rates and to find alternatives to prison terms. The solution in many jurisdictions has been the implementation of “specialty courts” that address societal issues that have made their way into the courtroom. These specialty courts involve working with defendants that have ended up in the criminal justice system due to drug or substance abuse issues, mental health issues, or co-occurring disorders. The premise of these courts is that these individuals are not criminogenic by nature and are instead stuck in a cycle of committing crime to support their substance abuse or their behavior is due primarily to an untreated mental illness. The court provides these individuals with the treatment they need and would likely not receive in prison in order to reduce criminal behavior and ultimately recidivism rates.

The first specialty court was established in Dade County, Florida in 1989 (Frailing, 2016). It was created as a specialty drug court to help individuals who found themselves in the court system for crimes such as possession, trafficking, or even theft to support a drug habit. Instead of these people pleading to their crimes and being sentenced to a prison term where they would receive little if any substance abuse treatment and counseling, the court brought all the parties together as a team to incentivize the individual into getting help for their underlying issues. What made this so unique was that it brought prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys, treatment providers, and defendants into a room to work together in a system that has always been at its core, adversarial in nature. Since this first court was implemented, it has seen incredible success rates prompting other courts to launch programs of their own. As of 2020, there are now over 3,848 different specialty courts in the United States that are working to address the underlying issues behind criminal behavior (Center, 2020).

Despite the successes these courts have seen in the past 30 years, there are always some that fail. What these failing courts have in common is that they often require defendants to plead to the crimes they have been charged with and offer very little sentence or probation reduction. For example, the federal court in the District of Maine currently has a program called SWiTCH (Success With the Court’s Help). This program has been known to be incredibly unsuccessful since it was established, and many people feel the program should be abolished. I investigated why this program was so unsuccessful when other specialty courts across the country have had the opposite results. Here is what I found:

The SWiTCH program is not a part of the actual court system and instead is a drug treatment program that individuals can enter while on supervised release. They must have plead guilty to their charges in court and served their entire prison sentence first before ever being considered for the SWiTCH program. This means their criminal record remains unchanged and the amount of prison time served is not altered. The only incentive for individuals entering the program is that if completed successfully, they will receive one year deducted from their supervised release. Meetings are held on a monthly basis where individuals check in with the judge, prosecutor, defense counsel, and their treatment provider (Justice, 2021).

As you may have guessed, this program offers little incentive for individuals to complete the program successfully, and the frequency of check-in meetings provides very little oversight for those struggling with substance abuse addiction. Fundamentally, this program was set up to fail. This program is the only type of specialty court offered in the federal court system in the District of Maine and demands a complete overhaul in order to be effective.

It is important for courts and communities who wish to address societal causes of criminal behavior to explore successful and unsuccessful specialty court programs to ensure they don’t encounter the problems seen within the SWiTCH program in Maine. As with most social justice programs, it is important that all facets are well researched prior to implementation in order to achieve success. Without it, you are doomed to failure.

Resources:

Center, N. D. (2020). Treatment Courts Across the United States. Retrieved from National Drug Court Resource Center: https://ndcrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2020_NDCRC_TreatmentCourt_Count_Table_v8.pdf

Frailing, K. (2016, April 11). The Achievements of Specialty Courts in the United States. Retrieved from Scholars Strategy Network: https://scholars.org/contribution/achievements-specialty-courts-united-states

Justice, D. o. (2021). SWiTCH (Success With The Court’s Help). Retrieved from United States Probation and Pretrial Services - District of Maine: https://www.mep.uscourts.gov/switch-success-court%E2%80%99s-help

Women Incarcerated: Basic Right Inequity

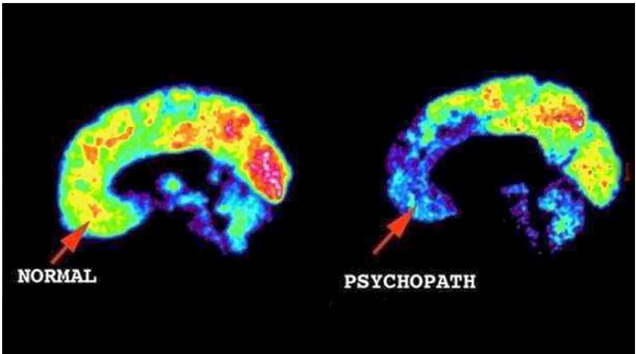

I think it is important to analyze and discuss the trauma that woman face within the carceral system. We always discuss the trauma that individuals go through before prison, but I think it is time we talk about the trauma that surfaces within the facilities. When it comes to women, they have different situational needs that differ from men. Before incarceration woman face many adversaries and it continues in prison. For women, it is important to realize that the most common reasons for women to commit crimes are based on survival of abuse and poverty and substance abuse. Their actions can be results of many different issues, including mental illness, trauma, substance abuse and addiction, economic and social marginality, homelessness, and relationship issues (1). Programs need to be focused on individualized reformation and focus on rehabilitation. A larger percentage of women are diagnosed with major depression and anxiety disorders, especially PTSD. Most women in the system (up to 70%, possibly even more) report histories of abuse as children or adults. Additionally, a greater percentage of women have histories of substance abuse than men (2). Statistics like these are reasons why women need equality but needs specialized focused programs. Unfortunately, women face trauma before, during, and after, it is an endless cycle.

I think it is important to analyze and discuss the trauma that woman face within the carceral system. We always discuss the trauma that individuals go through before prison, but I think it is time we talk about the trauma that surfaces within the facilities. When it comes to women, they have different situational needs that differ from men. Before incarceration woman face many adversaries and it continues in prison. For women, it is important to realize that the most common reasons for women to commit crimes are based on survival of abuse and poverty and substance abuse. Their actions can be results of many different issues, including mental illness, trauma, substance abuse and addiction, economic and social marginality, homelessness, and relationship issues (1). Programs need to be focused on individualized reformation and focus on rehabilitation. A larger percentage of women are diagnosed with major depression and anxiety disorders, especially PTSD. Most women in the system (up to 70%, possibly even more) report histories of abuse as children or adults. Additionally, a greater percentage of women have histories of substance abuse than men (2). Statistics like these are reasons why women need equality but needs specialized focused programs. Unfortunately, women face trauma before, during, and after, it is an endless cycle.

Within the correctional system there is still many states without legislation or mandates on period products. In 2017, only 12 states and the District of Columbia have passed menstrual equity laws that require no cost menstrual products in state prisons, which means most incarcerated people in the United States still have limited access to the period products they need.

Many of these women must beg, borrow, or make their own sanitary products, this proves that there is no dignity, compassion, or humanity in the system. Over the years pads and tampons have become weaponized in the system. “I know women who made products out of shreds of clothes or stuffing from inside their state-issued mattresses and were subsequently penalized for destroying public property.” This isn’t only embarrassing but it carries great health risks as well. These makeshift products can lead to toxic shock, infections, and infertility (3).

In Connecticut, commissary sold a pack of pads for $2.63. Prison jobs in Connecticut they pay as low as 30 cents per hour. “Assuming that a woman has a five-day menstrual period, each month and changes her tampon at 8-hour intervals, the maximum time suggested by gynecologists, a woman using tampons at NCCW is spending 25% of her annual salary on feminine hygiene products” (3). With that wage any of these individuals cannot afford it on top of other necessities like doctor’s visits, acetaminophen, or a phone call to a loved one. Some women even turn down visits with their family or even turn down visits with their attorneys, which can have a huge impact on their time incarcerated within the whole process (3).

In Connecticut, commissary sold a pack of pads for $2.63. Prison jobs in Connecticut they pay as low as 30 cents per hour. “Assuming that a woman has a five-day menstrual period, each month and changes her tampon at 8-hour intervals, the maximum time suggested by gynecologists, a woman using tampons at NCCW is spending 25% of her annual salary on feminine hygiene products” (3). With that wage any of these individuals cannot afford it on top of other necessities like doctor’s visits, acetaminophen, or a phone call to a loved one. Some women even turn down visits with their family or even turn down visits with their attorneys, which can have a huge impact on their time incarcerated within the whole process (3).

When it came to asking guards for a menstrual product, there is a certain power dynamic between the guards and inmates that created a sense of humiliation even thought this is a basic need. Sometimes guards would use manipulation and blackmail against the inmates and used their power to go above them. According to a 2019 Period Equity and ACLU report, a Department of Justice investigation found that correctional officers at Tutwiler Prison for Women in Alabama coerced incarcerated people to have sex with them in exchange for access to period products (3).

This even is affecting young women too, there is a youth rehabilitation and treatment center in Geneva. This place houses girls anywhere from age fourteen to nineteen. Even they had to pay for their own feminine hygiene products. The young girls can’t earn money while in the home, so it is entirely up to the families. The problem rests on the fact that some families are poor and cannot afford to travel to visit them let alone afford these sanitary products for them.

Every individual has a right to personal hygiene whether you're incarcerated or not. Giving woman sanitation products and focusing on women health is a major factor that needs to be included in personal treatment plans for women in prison. The deny of these basic rights reinforces any kind of powerlessness you have ever felt in your life.

Resources

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2021). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach.

Lee, J. (2021, July 1). 5 pads for 2 cellmates: Period products are still scarce in prison. The 19th. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://19thnews.org/2021/06/5-pads-for-2-cellmates-period-inequity-remains-a-problem-in-prisons/?amp

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 4: Implementing Psychology in the Criminal Justice System. [Lecture Notes]. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Is it trauma-informed?

In some of my previous discussions, I have described my experiences as a juvenile detention officer and what kind of programs the facility has. It seemed that the more I learned throughout this course, the more surprised I was with the lack of trauma-informed programs and practices at my place of work. Considering the frequency with which I see kids who have a plethora of traumatic experiences and mental health problems, I wanted to examine one program we run in the facility and analyze how trauma-informed it truly is.

Generally speaking, the programs that are run within our facility are a means to occupy the minors, keep them active, or fulfill some type of school-based requirement as a primary goal. It appears that having well-rounded, trauma-informed, and healing programs is secondary to that. Along with programs such as sex education and big brothers big sisters, our facility has a yoga instructor come in every week day to lead an hour-long class. Sometimes, the hour of yoga is the only structured physical activity the minors have throughout the day, and therefore, it fulfills their physical education requirement. At times, the youth aren’t engaged in the yoga. Often times, especially if yoga is in the morning, they will just lay there and sleep- claiming that they are “meditating.” Personally, I think it would be helpful to have more discussion with the kids about what kind of impact the yoga has on them and how they can use the time to be mindful, as “Even though a yoga instructor may try to proceed with the best of intentions, they may not realize that without proper training on trauma-informed yoga, they could be leaving certain youth feeling disempowered and marginalized” (OGyoga).

The TIMBo program has three objectives of: providing accessible tools for coping, gain awareness of the body, and begin a process of transformation (Rousseau & Jackson, 2014). The program I am familiar with is essentially just a yoga class, without identifiable objectives, and rarely any discussion with the participants or indication that the class is meant to do more than help them be relaxed or flexible. Benefits of trauma-informed yoga include emotional awareness, increased self-esteem, improved ability to identify negative behavior, improved conflict resolution (OGyoga), decreased anxiety, decreased trauma symptoms, and increased self-compassion (Rousseau & Jackson, 2014). Our current program could provide those same benefits if instructors and staff were trained and youth were engaged in a more meaningful and knowledgeable way.

Trauma-informed services are safe, predictable, structured, and involve repetition in order to avoid triggering trauma reactions, support coping capacities, and provide some kind of benefit from the service (Rousseau, 2021). Overall, I think taking the time, efforts, and resources to update the existing program would be worth it. Often, we are told to be mindful of trauma that the kids experience, but we are given training that seems inadequate and do not provide them with programs that are substantial enough to address their trauma. Especially since incarceration itself can be traumatizing, we need to maximize the potential of existing programs and implement others in order to best serve the youth and help them heal. Although the current program is safe and structured, I do not think it is trauma-informed. The purpose of the program and structure of it was not made to intentionally respond to and aid the youth in this way, therefore, the youth cannot gain the same benefits they would from a truly trauma-informed yoga class.

References

Burrell, S. (n.d.). Trauma and the environment of care in juvenile institutions. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources/trauma_and_environment_of_care_in_juvenile_institutions.pdf

OGyoga. (2018). Benefits of yoga for youth who have experienced trauma. Retrieved from https://www.ogyoga.org/resources/2018/2/8/benefits-of-yoga-for-youth-who-have-experienced-trauma

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 4: Implementing psychology in the criminal justice system. Retrieved from https://learn.bu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-9312167-dt-content-rid-57732979_1/courses/21fallmetcj725_o2/course/w4/metcj725_ALL_W4.html

Rousseau, D. & Jackson, E. (2014). yogaHOPE: Healing ourselves through personal empowerment. Retrieved from https://learn-us-east-1-prod-fleet02-xythos.content.blackboardcdn.com/5deff46c33361/3915210?X-Blackboard-Expiration=1639450800000&X-Blackboard-Signature=%2FsKuLigz%2FZWXITxDNSLpkjtyQsl%2FBRRz2u1Ua8JV5wo%3D&X-Blackboard-Client-Id=100902&response-cache-control=private%2C%20max-age%3D21600&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%2A%3DUTF-8%27%27w4_read_TIMBo2014.pdf&response-content-type=application%2Fpdf&X-Amz-Security-Token=IQoJb3JpZ2luX2VjEGcaCXVzLWVhc3QtMSJHMEUCIDbX7i4%2FUdN1FyWpa4YvUA9OXdUWl4PbvWyihcCdYrTbAiEAgzEuYiNoBEETgHcE5W%2FAIfLBVCtk44SAPgoZLEr8BXsq%2BgMIUBACGgw2MzU1Njc5MjQxODMiDOWGmjYfScfEwRbnZyrXA%2BUpqWiEio%2FC%2BaPuLxxgnsNDeuROz8TDyhwPRSZP8%2BgarYqIVnP%2BJQ1H08%2Be23OZkZRCFEDk%2FlL%2BCq%2BSpwrv7hdrE8Mw6ZYFwZigud6ucpTF9HdSTOdW6OWsViAZlfBQcjE0SVMtSmdMo5BSkONjpgTbvrZNZ1pJQCPAQ6KWtOsnLUwfyFAf1srlwDrWe1aakVRaNpkJVTFEnt4PIciappAAGDW4p2ZbRuualWc0%2BAY4GSAFjFoC24n%2FdGM6GTgm5c1dP%2BildfpepwI6pmGDWlpxkRp2bv755IKUFkx5SSsXnoL9V%2F2sDCeWlSNnvWcnfsMLEZpz3Bx0wSKqBwHkvpMdSOUfj0oeEudLKErXYI5rOvwvUSOPlEqJbOPDYdQC2oZqOCYSZZRwrTApECD%2Bsze5WVuRhtViQ7msg6Rzu39WNB%2BzK8sxPAEtbHrzTWUbZds08QFicUXoi6dUsP9GYfZBCAt%2BTeVTO6Iv8rKCtawxjhC3Sl7qGJM5b3Jjo2hSTq%2FGwg8qE%2BOlWV82QhKrL7WAT0n6LWAzjdrVdJ9uT8d%2F7CNU%2FAc27B%2F8PC8s5ZYQJmZfD0cNwxle1Fl9GWOMtVFZwL8Tl%2BZeK6SbFZCeMfBgVF99dSy5ADCeoN%2BNBjqlAe5F9vyFs%2FXdR47oEzyIn3tB4ex%2FZQgbrWMPtFJEO1nvgeH%2BCM58RVLGBpreCahDgI%2F2fZUyBvvtiUtK78cGNk28xgyhU1FAlIi6faiErKlXRkxeTTkyFY72M8ZL8%2Bn2jsDt%2F%2F44%2BRzD389ka3tygofYS9fikZe4B17XSxM%2BQXpm2BPsPu1Zu8g2CPadYi8Hs0nOZKZ%2Feur%2BftQVw1LLz7NeUjArMQ%3D%3D&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Date=20211213T210000Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=21600&X-Amz-Credential=ASIAZH6WM4PL7XQYCGEE%2F20211213%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Signature=ccfca75afac21ad3161a33d2f1a6ec305280acea1baa94efe52aab641f2a2314

Grief: Is It Possible to Have a Worthwhile Life After Sexual Abuse?

Rape, by definition, is an attack or an attempted attack that involves unwanted sexual contact with penetration, in a relationship between an offender and a victim, where the victim lacks the consent (Bartol, 2020). This definition seems to be very straightforward, however, it does not fully explain why a plethora of victims never report this act of sexual violence but go through mental, physical or both traumas and grieve. What does stand behind this complicated grief? Why are some treatments not effective? What are those psychological tricks that sexual offenders apply to their victims so that they question whether it is possible to live a worthwhile life or not after the sexual abuse they were exposed to?

Before shedding some light on the complexity of sexual-related crimes, it is worth it to look at some important facts: the victimization data on adult females within relationship factors. Precisely, 24.4 % of sexual assaulters are strangers, 21.9 % are husbands or ex-husbands, 19.5 % are boyfriends or ex-boyfriends, 14.6 % are acquaitances such as friends or neighbors and 9.8 % are relatives (Bartol, 2020). Thus, one can conclude that the majority of rape cases are indeed conducted by strangers and those who victims might have a relationship with. That being said, there is a puzzle being raised: why don’t rape victims report to the police about what happened to them and prefer to grieve in silence? Clearly, those rape cases that involve intimate partners might have a logical explanation since victims have fear to confess that their husband or boyfriend has exposed them to sexual violence, especially if an offender and a victim turn to have a family together, and a raped woman is willing to protect her children. However, what about those cases when a stranger is involved? What does stop a female to report the sexual crime if there is no personal connection to the perpetrator? To answer these questions, it might be informative to analyze the tapes of 911 calls that were made despite the unwillingness of victims to report.

Now, if we refer to 911 calls, it might be noticed that the relationship between a perpetrator and a victim is not that complete and obvious as it seems from the first sight. To illustrate this, an array of 911 calls show that a victim usually blames herself for the sexual violent acts occurred because, first, most likely this victim meets her perpetrator in the bar, next, typically the rape itself happens in the victim’s house, and finally, the victim emphasizes her fault since she was drinking alcohol that led to these adverse consequences (Sexual Assault, Media Education Foundation). From the tapes’ perspective, it becomes clear that the victim’s role in this relationship tends to get dual. In others words, we get a victim, a woman who realizes that she was exposed to sexual abuse and violations of her rights, and an “unnamed conspirator” who keeps whispering to this woman “listen, this is you who drank with him, invited him to your house, drove with him in your own car, and eventually brought him to your house”. The concept of an “unnamed conspirator” (Munch, 2012) is not new, it was developed by Anne Munch, an advocate for victims of sexual assault and stalking, who discovered the presence of the third side existing in the relationship between a victim and an offender. This theoretical discovery in the field of sexual-related crimes and trauma is very crucial because it demonstrates a strong influence of this “unnamed conspirator” that we can call as some sort of moral rules “follower” that dictates a victim to obey them, and since they were infringed, a victim experienced a terrible feeling of fault and sacrifices herself as a martyr who is exposed to suffering. And this is the moment when the grief comes into play. A victim is convinced by this “unnamed conspirator” that she has broken the moral code, and she prefers to isolate herself from society, thinking that this society will actually judge her since she was this initiator of the sexual act, she is convinced that it was not sexual assault or rape, it’s her who should be blamed in every single consequence. Thus, applying this theory we can conclude that a perpetrator exposes his victim not only to physical violent acts but also to psychological traps knowing in advance that the victim will “interact” with the “unnamed conspirator” and this element of their relationship will contribute to putting the victim into endless cycles of fault and grief, meaning there is a potential guarantee that she won’t report about him to the police. This scenario serves as a example of a violent culture that keeps growing especially in the community of young females who study at college (indeed, this victim profile is the most frequent one for perpetrators to deal with since young females find themselves irresponsible in a sense due to drinking in a bar and as a result going through basically negative consequences they have created themselves - this is a typical logic of a victim that was exposed to sexual violence by a stranger). This leads us to horrendous traumas that young women experience by binding themselves with “grief handcuffs” from their young age.

After this theoretical analysis, one should refer to traumas themselves. Particularly, this can be the rape trauma syndrome or post-traumatic stress disorder (Bartol, 2020). “Grief” argument is exactly related to this psychological traumatic experience because the main syndromes go around anxiety, feelings of helplessness, shame, depression or the development of phobias. However, it also does not exclude the physical malfunction either since rape trauma sydnrome includes sexual dysfynction as well. Now, the treatment for traumas linked to sexual abuse might seem to be simple to follow as it is usually advised to seek for a trauma therapist; join some supporting groups in order not feel alone or disclose to those ones who a victim trusts in order to feel support and overcome this crisis. This is why it is worth it to look at the Survivor Therapy Empowerment Program that was elaborated by Dr. Walker (2013). This program is based on the principles of trauma and feminist theories where she claims that the trauma healing should be based on safety planning, empowerment via self-care since it is a priority to take the power back to a survivor, overcoming depression to optimism and developing cognitive clarity (Walker, 2013). This treatment approach seems to be quite essential to apply for the victims of rape or domestic violence, and it was successfully developed within verbal therapeutic approaches that indeed can be a decent treatment for those who needs support and sense of belonging to the community to eradicate the feeling of loneliness.

However, these techniques are not necessarily effective and simple to apply for those victims who are trapped inside the “grief cycle” shaped by the “unnamed conspirator”. In order to find the proper treatment for these specific cases, one should understand what the grief cycle is. For example, the model of Kubler-Ross (1969) includes 5 stages of grief which are denial (the stage that helps the victim to survive “loss”), anger (the stage when the victim lives the terrible reality), bargaining (the stage of false hope), depression (the stage that represents the emptiness the victim feels) and acceptance (the stage when the victim tries to start living with what has happened). Having this knowledge in mind, it might be possible to consider another type of trauma treatment that involves 2 phases of therapy: medical and psychological. From the medical perspective, the prescription of medications such as sedatives or anti-depressants influences the victim inside while assisting in functioning the nervous system properly via supporting the sleep process and suppressing the grief during the day time. When it comes to the psychological approaches, counselling still might be a beneficial verbal therapy that as we can see from the above mentioned programs is capable of producing positive results. Nevertheless, an amalgam of both approaches should be applied since the grief cycle is not just a complex phenomenon consisting of different stages but also a mental trap that victims are exposed to in sexual violence and it requires a complex treatment that doesn’t leave aside neither the physical nor mental elements of a female body.

Works cited

- Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2020). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach.

- Kubler-Ross E. (1969). On Death and Dying. 50th Anniversary Edition.

- Munch A. (2012). Sexual Assault: Naming the Unnamed Conspirator. Media Education Foundation.

- Walker L. (2013). Domestic Violence and Survivor Therapy Empowerment Program.

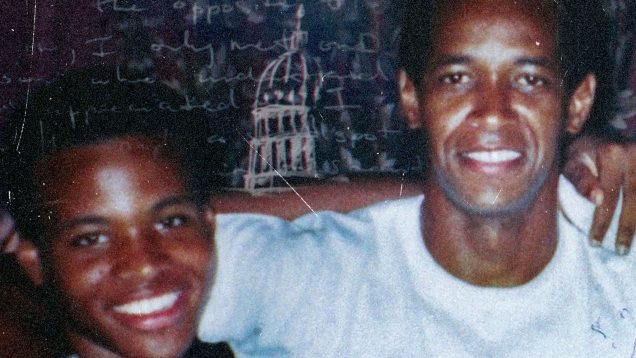

Was “DC Sniper Sidekick” Manipulated into Crime Spree?

On October 2, 2002, five people were gunned down by a long range rifle in a fifteen hour span in Montgomery County, MD. Over the next three weeks, these sniper-style shootings were occurring all throughout the DMV area, terrifying everyone. These shootings were happening in broad daylight and the victims were randomly selected. Age, race, and gender did not seem to mater. Locals were hiding behind their vehicle's while pumping gas, school recess was being held indoors, and sports practices were cancelled because no one wanted to be the next victim. Finally, the attacks came to an end with the shooters, John Allen Muhammad (41) and Lee Boyd Malvo (17) were arrested while sleeping in their car, without incident, at a rest stop in Maryland. The dark blue Chevrolet Caprice was found to have a hole in the trunk that was able to fit a sniper-rifle barrel through it. The prime suspect, John Allen Muhammad admitted that the motive of the shootings was to eventually kill his ex-wife by making it look like it was apart of these random shootings. Muhammad was a former US Army sniper and Gulf War Veteran. He was awarded the highest award for marksmanship in the Army (Washington, D.C. sniper John Muhammad convicted 2009). The upbringing of his accomplice, Lee Boyd Malvo was a little bit different.

According to The Atlantic, "he became wrapped up in John Allen Muhammad's wickedness...the older man controlled his understudy, controlled him to the point of hypnosis. All the kid wanted was a decent father, and when his own dad failed to be there for him, he allowed another man, a truly evil man, to play the part. The result is a mournful story with a Shakespearean arc" (Cohen, 2012). Malvo was born in Kingston, Jamaica to a single mother and bounced from family member to family member while his mom worked. His mother moved them to Antigua in hopes of a better life for her and her soon. It was in Antigua that Malvo first meet Muhammad where he quickly became a father figure. “The groundwork was laid in Antigua because I leaned on him, I trusted him, Malvo said. I was unable to distinguish between Muhammad the father I had wanted and Muhammad the nervous wreck that was just falling to pieces. He understood exactly how to motivate me by giving approval or denying approval. It’s very subtle. It wasn’t violent at all. It’s like what a pimp does to a woman” (White, 2012). Throughout Malvo's life he claims to have been sexually abused starting from the age of five by a babysitter, throughout his life by family members, and also by Muhammad. The three of them moved to Florida where Malvo's mother practically gave him away to Muhammad. Three years after moving to Florida is when the murder spree began. After their arrest, Malvo was so manipulated by Muhammad that when he found out the death penalty was more prevalent in Virginia, he originally took the blame for all of the shootings (White, 2012).

In an interview conducted by Matt Lauer with the Today Show, Malvo was quoted saying, “The main reason I'm coming forward now is because I am more mature. As far as the guilt that I carried around for several years, I dealt with that to a large extent for years. And now, I can handle this. In here, there's no therapy. Rehabilitation is just a word. In solitary confinement, in a cell by yourself, I am priest, doctor, therapist. So, it just worked out that I just took it off piece by piece. That I could handle it" (Sager & Stump, 2012). It seems now that Lee Boyd Malvo is no longer under the spell of John Allen Muhammad and understands the amount of damage that he has caused. After a six week trial, John Allen Muhammad was given the death penalty and Lee Boyd Malvo was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Do you think this was a fair sentence for Malvo? If it were not for Muhammad how much different would Malvo's life have been?

References:

A&E Television Networks. (2009, November 13). Washington, D.C. sniper John Muhammad convicted. History.com.

Cohen, A. (2012, October 1). The making, and unmaking, of D.C. sniper Lee Boyd Malvo. The Atlantic.

Sager, I., & Stump, S. (2012, October 25). D.C. sniper Lee Boyd Malvo: I was sexually abused by my accomplice. TODAY.com.

White, J. (2012, September 29). Lee Boyd Malvo, 10 years after D.C. area sniper shootings: 'I was a monster'. The Washington Post.