Solitary Confinement, Mental Illness, and Trauma

The utilization of solitary confinement in prisons is extremely harmful mentally, physically, and socially. Moreover, the effects of this extreme isolation for those with mental illnesses is especially damaging, and can cause further trauma and worsen the mental disorder. Despite the vulnerability, those with mental illnesses are both over represented in prisons and in solitary confinement units. Furthermore, solitary confinement is particularly dangerous when utilized on one with trauma of any kind, whether from past abuse, a mental illness or prison itself. Efforts must be taken to remove solitary confinement from being used on those who are mentally ill, and only enforced if a crime within prison is heinous, or the inmate is a specific threat to others or him/herself. The confinement itself is not worth the trauma it creates, as it is largely neither cost effective, nor solves problems only exacerbates them. Moreover, there is an argument to be made that solitary confinement, specifically for those who are mentally ill violates the eight amendment, and that it should be removed. Overall, solitary confinement, specifically for those who are mentally ill or have undergone extreme trauma can be likened to torture and worsen mental health symptoms.

Solitary confinement is defined as “the physical isolation of individuals who are confined to their cells for 22.5 hours or more per day” (Leonard, 2020). The inmates are “encased in concrete and steel” with enforced steel walls, and doors (Skibba, 2018). The cell contains a metal bed, small toilet and often not even a window for natural light. The entirety of the cell is about the size of a small elevator where the inmates are locked up like animals in a cage (Skibba, 2018). It is common for inmates to loose their grip on reality, experiencing the same smells, slights, and limited range of motion every day on repeat (Skibba, 2018). The length of time one can be confined can range anywhere from a couple of hours to days, to weeks and even to years. One inmate even spent 40 years in solitary confinement (Leonard, 2020).

The use of solitary confinement is used as a form of punishment for three main reasons. The first is disciplinary segregation, or punishment for breaking rules, the second is temporary segregation, or being isolated due to a physical altercation, and the third is administrative segregation, or isolation of one who presents an ongoing threat to the safety of themselves and, or others (Leonard, 2020). Further, while its original use was for protective custody or housing violent prisoners, the use of solitary confinement is now used predominantly for minor crimes. While nations such as Germany utilize isolation for serious acts of violence only, the United States frequently uses isolation to punish for minor offenses and inmates breaking basic rules. A study conducted in Illinois in 2015 found that 85% of those incarcerated who had been placed in solitary confinement had been done so for minor offenses. Moreover, the United States uses solitary confinement for longer periods of time than any other nation, with up to 80,000 people in isolation per day, not including juvenile facilities (Leonard, 2020)

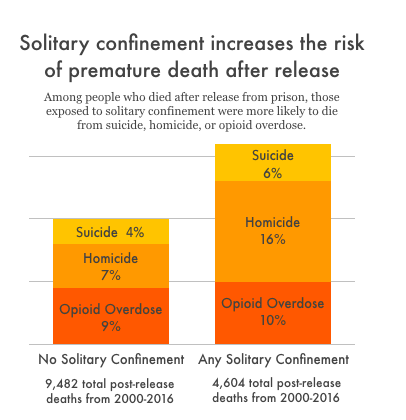

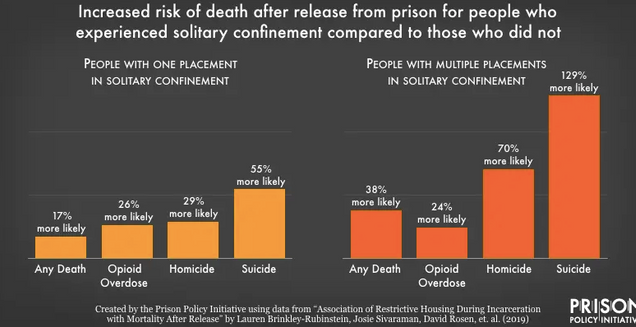

The effects of solitary confinement range from physical, to emotional and mental problems depending on the length of time one is isolated for. Mental health problems can include: anxiety and stress, depression, hopelessness, anger, irritability, hostility, panic attacks, hypersensitivity to sounds and smells, hallucinations, paranoia, poor impulse control, social withdrawal, violence, psychosis, fear of death, and even suicide and self harm (Leonard, 2020). Suicides occur more in segregation units than anywhere else in the prison (Metzner, 2010). In fact, around half of what is deemed, “successful suicides” occur housed in solitary confinement. Due to the limited methods for suicide in both isolation regular cells, creative and often gruesome methods of suicide are utilized and attempted (Dillon, 2019). Furthermore, even if the inmate is both sane and has no mental disorder entering solitary confinement, some have been stated to leave with mental health symptoms and paranoia that were not present prior (Dingfelder, 2012). While, “Prisons and jails are already inherently harmful, and placing people in solitary confident adds an extra burden of stress that has been shown to cause permeant changes to peoples brains and personalities” (Herring, 2020). Studies have even stated that after release from prisons, those who have undergone time in solitary confinement are more likely than others to either die via suicide, or reoffend and come back to prison. The data from the JAMA study in North Carolina found that those in isolation were 24% more likely to die within the first year of release from prison. Specifically, those in isolation were 78% more likely to commit suicide and overall 127% more likely to die of an opioid overdose (Stagoff-Belfort, 2019).

An extensive problem one endures in solitary confinement is the obvious presence of social isolation. People are not created to be alone, and be isolated beings. Emotional, social and physical contact are largely necessary for one to live. Without the comfort of others, and constantly being alone, ones risk for depression and anxiety due to the intense loneliness increases. Researchers note the powerful connection between isolation and psychiatric illnesses, in addition to worsening one’s current mental illnesses (Cruel, 2019). Social isolation can also lead to elevated cortisol levels which are related to an increase in blood cholesterol and blood pressure (Dillon, 2019) The extreme loneliness, and solitary confinement itself “requires people to learn to live in a world without people…It is the medial of meaningful social engagement with others” (Skibba, 2018). When released they are often incapable of living back in either normal society or amongst the general prison population. “They are overwhelmed with anxiety…they become frightened of other human beings” (Dingfelder, 2012).

Moreover, there are many physical health problems that can result from isolation. These physical health effects include: chronic headaches, deteriorated eyesight, digestive problems, dizziness, lethargy and fatigue, heart palpitations, hypersensitivity to light and noise, loss of appetite, sleep problems, weight loss, and muscle and joint pain. Further, due to the lack of natural light, vitamin D deficiency can occur leading to weakness, depression, and brittle bones. Further, confined to their cell, inmates undergo little to no physical activity. This often leads to a difficulty to manage high blood pressure, heart diseases and further, one becoming more anxious, hopeless and depressed (Leonard, 2020). Moreover, researchers Jules Lobel and Huda Akil state that the utilization of solitary confinement can alter various brain components such a the hippocampus which is involved in stress and memory. The damage can lead to a loss of emotional stress control, decreased cognitive processes, and severe depression. Research has found that even being in solitary for only a few days, ones electroencephalogram test results demonstrate abnormalities that reflect states of delirium and numbness (Cruel, 2019). Jack Abbott, who spent a large amount of time in solitary confinement stated that “the lethargy of months that add up to years…alone…entwines itself about every physical activity in the living body and strangles it slowly to death” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1781).

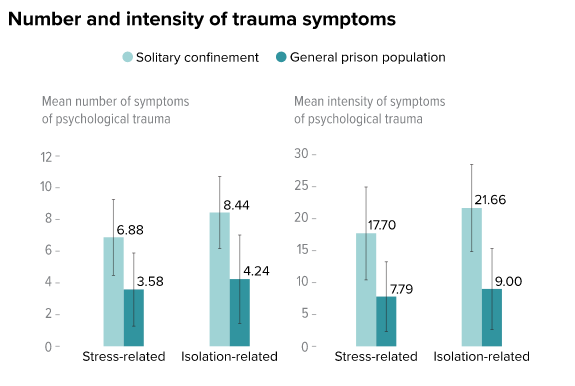

While the effects of solitary confinement contain traumatic elements that impact even regular prisoners, its effects are worsened when one has already undergone trauma or has a mental illness. One study cited that the effects of solitary confinement “are analogous to the acute reactions suffered by torture and trauma victims” (Hagan, 2017). The implementation of a traumatic event on top of one who has undergone intense trauma can lead to self harm and possible suicidal attempts (Hagan, 2017). Studies have identified that various aspects that occur in isolation and the psychological stressors that occur are similar to and “can be as clinically distressing as physical torture” (Dillon, 2019). Similarly, those who are mentally ill experience elevated rates of their symptoms including anxiety and hallucinations after solitary confinement (Hagan, 2017). The lack of social contact, stress, isolation and trauma from solitary confident can “exacerbate symptoms of illness or provoke recurrence” (Metzner, 2010). All in all, the risk of “something more permanent and disabling” in terms of trauma is exacerbated if one has preexisting mental trauma (Dillon, 2019). Furthermore, in addition to worsening symptoms access mental health treatment options are limited and often unavailable while in isolation. There is no group or individual therapy, life skill activities, or other interventions allowed. The most a mental health professional can discuss with the inmate is asking if they are okay and coping with the isolation (Metzner, 2010). Those who are mentally ill are also more likely to commit suicide or engage in self harm acts after being released from isolation.

Moreover, excessively problematic is the amount of those who are mentally ill who are sent to solitary confinement. As stated, they are at greater risk for suicide and exacerbating mental health issues that other inmates, however continue to be sent to isolation. Due to various mental illnesses, prisoners can often act and “exhibit bizarre, annoying, or dangerous behavior and have higher rates of disciplinary infractions than other prisoners” (Metzner, 2010). This is often seen as said individual both breaking the rules and acting out. Instead of understanding and assessing whether the behaviors are a result of a mental disorder, the inmate is often sent straight to solitary confinement. Furthermore, once in isolation, the inmate can exhibit further misconduct due to the further trauma and isolation, lengthening the time in solitary confinement (Metzner, 2010). Moreover, the NCCHC stated that the “placement of inmates with serious mental illness in settings with extreme isolation is contraindicated because many of these with psychiatric conditions will clinically deteriorate or not improve” (Metzner, 2010). Similarly concerning trauma, those sent to isolation due to misbehaviors bizarre behavior may be due to fear and anxiety not the anger and frustration that corrections believes they are identifying. Along these lines, more than 43% of women as opposed to 12 percent of men have been sexually assaulted and undergone sexual trauma, and the stressors and further trauma in prisons often worsens their conditions and anxiety (U.S Department of Justice, 1998). For example acts of self violence in women have been declared as criminogenic and are often punished with said isolation as they are declared difficult and untreatable (Hannah-Moffat, 2006). Staff see acts of self harm as an attempt to manipulate staff or simply acting out due to anger, and send them straight to isolation, instead of seeing the issue for what it really is, a cry for help, a response to trauma, or extreme symptom of a mental illness (Dillon, 2019).

The severity of psychological harm has been even been described as being more “debilitating than physical harm” (Dillon, 2019, 291). In addition to this, the physical and emotional harm and trauma should trigger a necessary response in law makers to rid of solitary confinement as it largely violates the eight amendment, or the utilization of “cruel and unusual punishment.” In utilizing the word “cruel,” the courts “implied that cruel meant something inhumane and barbarous” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1761), and it can be argued that the combination of all the factors presented to an inmate in solitary confinement make this form of isolation uniquely devastating” (Cruel, 2019 , pg. 1773). Specifically concerning those with mental health issues, these individuals are undergoing punishment that denies them from access to life changing treatment and help. In putting those who are mentally ill in isolation, “confinement causes consistent, and sometimes irreversible psychological and physical harm” (Dillon, 2019, pg. 268), which can constitute as a cruel and unusual punishment, no matter the crime committed (Dillon, 2019). Further, the use of long term solitary confinement has been deemed both cruel and unnecessary and can lead to “irreparable human damage” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1783). When visiting Cherry Hill Prison, Charles Dickens noted that the use of solitary confinement and the “slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the mind to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1775), holding its usage to be both “cruel and wrong” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1773). While it does not involve torture to the body specifically, using “whipping, the breaking wheel, [and] disembowelment” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1778), “it is a quiet and invidious form of punishment that amounts to torture” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1779). Further, the use of solitary confinement when reintroduced in the 1980s can be declared unusual, as it “never became a “usual” practice after it first arose…nearly every date explicitly rejected the practice after they saw the detrimental effects it had” (Cruel, 2019, pg. 1759).

Significantly, there is “no evidence that administrative uses of segregation have any positive effect reducing or controlling gangs in prison” (Skibba, 2018). Further, the solitary confinement is not cost effective, often worsens the issues that are attempted to be solved, including aggression and hatred towards guards and other inmates, and does not achieve the overall outcomes (Leonard, 2020). The effects of solitary confinement on general inmates and specifically those with mental illness and distinct trauma is massive, and largely not worth the costs it creates. Due to research and analysis regarding this topic, many mental health professionals have attempted to eliminate solitary confident for mentally ill inmates. Instead these inmates who violate the rules inside prisons will be moved to a clinical setting where they will be treated at high levels consistently with the aim of “promoting treatment adherence and prosocial behaviors”(Venters et al, 2014). Moreover, this plan, created by the NYC Department of Corrections and Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, planned to establish mental illnesses in terms of serious to mild and moderate in order to create specific plans of violating prison rules. Those with mild behavioral problems will have more specific rules and regulations while in prison such as no outside time and recreational activities, instead of lengthily solitary confident (Venters et al, 2014). While, there is some credence to solitary confinement being utilized for dangerous criminals who are a danger to others and themselves, said confinement should be limited to inmates whose actions are as such. Isolation should not be given for minor offenses and small outbursts, and moreover the inmate responsible for each act thought to be punished should be assessed thoroughly and screened for prior intense trauma or mental illness that may have been responsible for said action. Standards of assessment should be rigid and programs such as the STAIR model are taking a step in the right direction. This model includes screening, triage, assessment, intervention and re-intervention, with a large focus on screening for mental illnesses and trauma, before intervention and treatments are implemented (Simpson, 2022). While efforts such as these are being considered, studied, and understood as growing in necessity, more needs to be done to remove and place restrictions on solitary confinement in prisons.

Resources:

Bartol, C., & Bartol, A. (2021). Criminal behavior: A Psychological Approach (12th ed.). Boston: Pearson. https://reader.yuzu.com/reader/books/9780135618813/epubcfi/6/2[%3Bvnd.vst.idref%3Dcover]!/4/2%4054:44

Calloway, K. (2019). I Spent 16 Months in Solitary Confinement and Now I’m Fighting to End It. Retrieved 11 August 2022, from https://www.aclu.org/blog/prisoners-rights/solitary-confinement/i-spent-16-months-solitary-confinement-and-now-im

CRUEL, UNUSUAL, AND UNCONSTITUTIONAL: AN ORIGINALIST ARGUMENT FOR ENDING LONG-TERM SOLITARY CONFINEMENT. (2019). American Criminal Law Review, 56(1759), 1759-1783. Retrieved from https://www.law.georgetown.edu/american-criminal-law-review/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2019/06/56-4-Cruel-Unusual-and-Unconstitutional-An-Originalist-Argument-for-Ending-Long-Term-Solitary-Confinement.pdf

Dillon, R. (2019). Banning Solitary for Prisoners with Mental Illness: The Blurred Line Between Physical and Psychological Harm. Northwestern Journal Of Law & Social Policy, 14(2), 266-292.

Dingfelder, S. (2012). Psychologist testifies on the risks of solitary confinement. American Psychological Association, 43(9).

Fenster, A. (2020). New data: Solitary confinement increases risk of premature death after release. Retrieved 11 August 2022, from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/10/13/solitary_mortality_risk/

Hagan, B., Wang, E., Aminawung, J., Albizu-Garcia, C., Zaller, N., & Nyamu, S. et al. (2017). History of Solitary Confinement Is Associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms among Individuals Recently Released from Prison. Journal Of Urban Health, 95, 141-148. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0138-1

Hannah-Moffat, K. (2006). Pandora’s Box: Risk/need and gender responsive corrections. Criminology & Public Policy,5(1), 183–192

Herring, T. (2020). The research is clear: Solitary confinement causes long-lasting harm. Retrieved 10 August 2022, from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/12/08/solitary_symposium/

Leonard, J. (2020). Effects of solitary confinement on mental and physical health. Retrieved 10 August 2022, from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/solitary-confinement-effects

Metzner, J., & Fellner, J. (2010). Solitary Confinement and Mental Illness in U.S. Prisons: A Challengefor Medical Ethics. Journal Of The American Academy Of Psychiatry And The Law, 38(1), 104-108.

Simpson, A., Gerritsen, C., Maheandiran, M., Adamo, V., Vogel, T., & Fulham, L. et al. (2022). A Systematic Review of Reviews of Correctional Mental Health Services Using the STAIR Framework. Front Psychiatry, 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.747202

Skibba, R. (2018). The Hidden Damage of Solitary Confinement. Retrieved 10 August 2022, from https://knowablemagazine.org/article/society/2018/hidden-damage-solitary-confinement

Stagoff-Belfort, A. (2019). Study Links Solitary Confinement to Increased Risk of Death After…. Retrieved 10 August 2022, from https://www.vera.org/news/study-links-solitary-confinement-to-increased-risk-of-death-after-release

U.S Department of Justice. (1998). Women Offenders: Programming Needs and Promising Approaches. National Institute of Justice

Venters, H et al. (2014). Solitary Confinement and Risk of Self-Harm Among Jail Inmates. American Journal Of Public Health, 104(3), 442-447.

2 comments

Hello Jessica,

I always knew that solitary confinement could have a negative effect on the prisoner’s mental state but I never realized to what extreme. Your post really shed some light on the realities of what being confined to a small cell can do for a person who is already suffering some sort of trauma or mental illness. Overall it seems as thou it can has way more negative effects than positive. You may have sent a prisoner to solitary confinement being of their behavior but when they get out of that confinement there is no positive change to the behavior so in reality, it could make the situation worse long term. More focus on mental health and a prisoner’s mental state should be incorporated in prisons in order to rehabilitate.

Great blog post, Jessica. Your use of information and graphics made it informative but easy to comprehend. Your post enlightened me as to the physical trauma inmates endure during solitary confinement. The alteration of brain matter, such as the hippocampus, surprised me at first, but upon further examination, it made sense due to the fight-or-flight response while living alone.

Overall, an insightful post!

Cady

Comments are closed.