American Systems of (In)Justice

The United States’ systems and mechanisms for law enforcement, incarceration and punishment, and post-conviction supervision, and social support are unique in all the wrong ways.

Over-policing policies and practices of the late twentieth century targeted, harassed, arrested, and imprisoned predominantly poor and Black Americans for non-violent crimes at an unprecedented rate. This legacy endures today when one in eighty-one Black Americans are currently behind bars (Nellis, 2021), a rate five times that of White Americans. The coincident dismantling of public health and education institutions and many social safety nets created tremendous wealth inequity in the world’s biggest economy, placing severe economic pressure on the poorest and most marginalized communities. Generations were lost to mandatory minimums or three-strikes life sentences.

Many White American exurbanites feigned surprise at this crusade and subsequent humanitarian mass incarceration crisis while tuning in to cheer on maverick police on prime time shows like COPS with no regard for those “criminals” who were hunted and vilified before charge or trial. Premiering in 1989, 8 million viewers (Chiu, 2020) participated in exploiting unwitting reality television participants representative of the most vulnerable and marginalized communities (e.g., sex workers, substance users, those living with mental illness, and the homeless). The show endured for twenty-five seasons, as hundreds of suspects referred to in the opening credits as “bad boys” were chased, tackled, and shackled into the back of police cruisers, easily written off by millions of viewers as wholly expendable, and disappeared into the criminal punishment system. COPS rebooted and then was dropped amidst protests following the murder of George Floyd, only to be rebooted again on the Fox streaming service for a new generation of sycophantic viewers. Fox afforded police a complimentary year-long subscription.

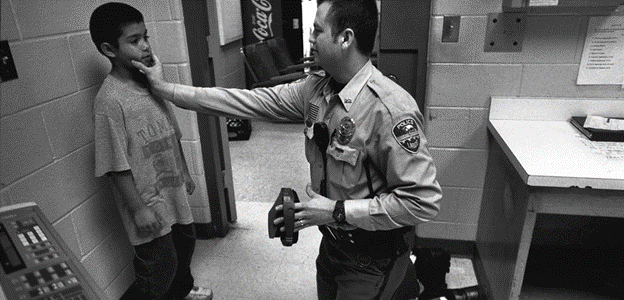

Children as young as 6-years-old have been detained and taken from their school in handcuffs, placed in the back of a police cruiser while outraged teachers live-stream this childhood trauma on social media. Viewers tune in to watch in shock and then apathetically scroll on.

Police in the US target and arrest children at a rate of 1,995 per day (728,280 in 2018) (2021, May 4), and thirteen states have no minimum age for adult prosecution of children (2019, December 11). Police can legally question minor detainees in these states without a guardian present and are free to use the same interrogative pressures as they would on an adult suspect.

Children as young as eight-years-old have been tried and punished as adults, and sent to adult prisons prior to and after conviction, where they are especially vulnerable to sexual, physical, and psychological abuse (2019, December 11). Black children are two-and-a-half times more likely to be arrested than White children and represent 41% of incarcerated minors. They are nine times more likely to have their cases transferred to and tried in adult court, (54% of minor cases) despite constituting just 15% of the American youth population (2021, May 4).

At least one in three incarcerated minors has a disability, qualifying them for special education services. Those in adult prisons are unlikely to receive adequate if any educational services. Rikers Island houses hundreds of children, roughly one-fourth of whom are in punitive segregation at any one time, mostly during pre-trial detention (Franklin, 2014). The common and accepted use of solitary confinement (both punitively and preventatively for those deemed to be especially vulnerable) is devastating when levied on minors, as it deprives them of social interaction and mental stimulation during a crucial period of adolescent brain development. Children housed in adult prisons are more likely to suffer permanent trauma and are five times more likely to die by suicide than children held in juvenile detention centers (2021, May 4). Developmental psychologist Bruce Perry noted that most incarcerated children have already suffered significant loss and trauma, making them particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of isolation.

“[t]hey end up getting these very intense doses of dissociative experience… They end up with a pattern of activating this dissociative coping mechanism. The result is that when they’re confronted with a stressor later on, they will have this extreme disengagement where they’ll be kind of robotic, overly compliant, but they’re not really present…The interpretation by the staff is that they’ve been pacified. “We’ve broken him.” But basically what you’ve done is you’ve traumatized this person in a way that if this kid was in somebody’s home, you would charge that person with child abuse” (Franklin, 2014).

The United Nations has classified solitary confinement as a form of torture, overly harsh, and contrary to rehabilitation. International law prohibits the use of solitary confinement on children (2011). UN Special Rapporteur on torture Juan E. Méndez has warned,

“Considering the severe mental pain or suffering solitary confinement may cause, it can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment when used as a punishment, during pre-trial detention, indefinitely or for a prolonged period, for persons with mental disabilities or juveniles” (2011).

Although the number of people behind bars in US jails and prisons is now the lowest since 1995, it is still the largest percentage of incarcerated citizens of any country in the world, and for disproportionately long terms of imprisonment. As of 2018, 639 out of every 100,000 people in the US were incarcerated, a rate 13% higher than the next highest rate in El Salvador (564:100,000), and astronomically higher than England and Wales (131:100,000), France (93:100,000), and Germany (69:100,000) (Gramlich, 2021). One in seven people incarcerated in US prisons is serving a life sentence (Nellis, 2021). Since the 1970s, US carceral systems do not purport to be rehabilitative, and recidivism rates in the US (76.6%) are among the highest in the world (Benecchi, 2021).

If policing does not prevent crime and carceral punishments do not rehabilitate, what is the function of mass incarceration but the preservation of White supremacy and domination? The suffering of Black children and adults in America is etched deeply onto every bloodied page of our history that it should be known and felt by every living person. Yet, generations of passive onlookers have turned to indifference, accepting a system of punishment and cruel and unusual solitary confinement practices as unfortunate but necessary to insulate them from perceived danger and abate fear. The cost of indifference is too high, and the pace of reform too slow. We have a moral responsibility to wake up to the reality of profound suffering and enduring trauma which survived for our indifference. We have a moral duty to say, “no more.”

References:

Benecchi, L. (2021, August 8). Recidivism imprisons American progress. Harvard Political Review. Retrieved December 14, 2021, from https://harvardpolitics.com/recidivism-american-progress/.

Chiu, A. (2020, June 10). ‘Cops’ hooked viewers and angered critics for decades. now it’s canceled amid protests over police brutality. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 14, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/06/10/cops-tv-reality-cancel/.

Franklin, K. (2014, April 14). How locking kids in solitary confinement became normal. How Locking Kids in Solitary Confinement Became Normal. Retrieved December 14, 2021, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/witness/201404/how-locking-kids-in-solitary-confinement-became-normal.

Gramlich, J. (2021, August 18). America’s incarceration rate falls to lowest level since 1995. Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/16/americas-incarceration-rate-lowest-since-1995/.

Nellis, A. (2021, November 1). The Color of Justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project. Retrieved December 14, 2021, from https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/.

The State of America’s Children 2020 – youth justice. Children’s Defense Fund. (2021, May 4). Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.childrensdefense.org/policy/resources/soac-2020-youth-justice/.

Thirteen states have no minimum age for adult prosecution of children. Equal Justice Initiative. (2019, December 11). Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://eji.org/news/13-states-lack-minimum-age-for-trying-kids-as-adults/.

United Nations. (2011, October 18). Solitary confinement should be banned in most cases, UN expert says. United Nations. Retrieved December 14, 2021, from https://news.un.org/en/story/2011/10/392012-solitary-confinement-should-be-banned-most-cases-un-expert-says.

Figure 1: retrieved from: https://eji.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/mugshot-little-kid-by-steve-liss-1.jpg