Galia Petkova

Galia Petkova is a professor of literature at Eikei University of Hiroshima. She has been teaching and conducting extensive research on Japanese traditional performing arts and Japanese culture at universities in Europe, Canada, Indonesia, and Japan for over 20 years. She earned her PhD in Japanese Studies from SOAS, University of London. Her doctoral dissertation, “Performing Gender in Edo-period Kabuki,” explores the processes of construing ideals of femininity and masculinity on the stage and the fluidity of gender in premodern theatre and society that has influenced contemporary Japanese pop culture. Dr. Petkova has received numerous grants, including from the Japan Foundation and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and has undertaken research at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies for four years between 2014 and 2018. She has lived in Kyoto for 12 years, immersing herself in local culture. Her investigative interests are performing arts in Asia, focusing on Japan, and gender studies – cultural re/presentation of gender and construction of idea(l)s of femininity and masculinity in performative space. Dr. Petkova’s two more recent projects focus on regional performing arts in Japan and the female versions of all-male traditional performing arts and masculine kabuki heroes in Japanese culture.

https://www.eikei.ac.jp/english/academics/researcher/details_00328.html

Full conference abstract:

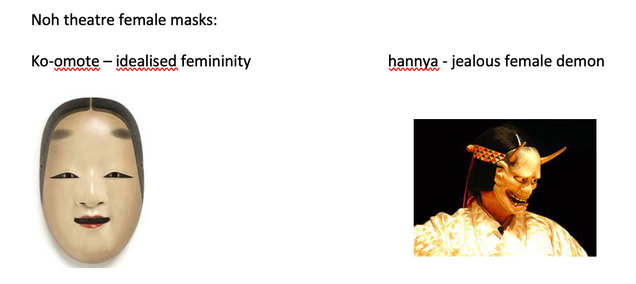

Similarly to other patriarchal cultures where masks were attributed a sacred nature, in Japan women were also excluded from the use of masks in traditional performing arts, which, moreover, were mostly male-dominated. Accordingly, the female masks were created and used by men, expressing specific visions of “ideal,” or “demonic,” or “plain-looking” femininity. Two of the mainstream genres employ masks. Bugaku, imported from the continent in the 6th-7th century and adopted as the performing art of the imperial court, features only supernatural masks that are not gender based and are generally deemed “foreign” and “exotic.” It was the noh theatre, which developed during the 14th-15th century as the performing art of samurai aristocracy, that gave birth to what is today considered representative Japanese masks. Of these, ko-omote, a symbol of idealised femininity, and hannya, the jealous female demon, are the most well-known and have even become representative of noh. This presentation focuses on one more female mask produced in Japanese culture – Okame, which is both ubiquitous, in the sense it could be found in various settings, and obscure, in the sense it is somehow undervalued and under-researched. The reason is in Okame’s origins in folklore and popular culture, of which it has remained a vital part, as opposed to the highly valued noh masks. Visually Okame is also drastically different from the latter – it features a broad brow, swollen round cheeks, and appears as always smiling. The mask is also called Otafuku “many fortunes” and is believed to bring good luck. Regarded as good omen, it can be often seen at markets and in agricultural settings. I will explore the legends of Okame’s origin and its usage throughout the centuries and today, focusing on the shifting significations of this “plain-looking woman’s” mask.