Chapter Summaries

Ch. 1: Golden Boy“My father used to tell me, as I tell my journalist son about news work, that lawyers don’t know anything, but have to be quick learners in a case in a new field.” Born 1910, Charlie grew up in New York City during the Roaring Twenties, which came to an end with the stock market crash of 1929, blighting his ambition for a career in international banking. Eager to avoid following his father into the law, instead he went to graduate school in economics at Columbia, starting spring 1933 just in time for Roosevelt’s March 1933 bank “holiday”. |

|

Ch. 2: Columbia“I have a strong impression that economics is a countercyclical industry that attracts adherents when times are troubled. Some are drawn to the subject by the opportunity to do good, to save the world so to speak by curing depression. The stronger drive in my view is curiosity. How does the economy work, and what has gone wrong?” At that time, Columbia was the center of American institutionalism. Within that frame, the main influences on Charlie were two: Henry Parker Willis who had played a key role in the founding of the Fed, and James Angell who was a key figure at the Council on Foreign Relations, a group of internationalists united by disappointment with the US failure to join the League of Nations. Charlie’s PhD dissertation International Short-term Capital Movements (1937) builds from both influences, in the direction of the key currency approach of John H. Williams, who was then splitting his time between Harvard and the New York Fed. |

|

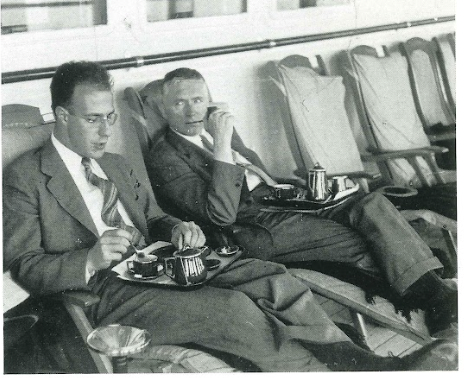

Ch. 3: Hot Money“This much is evident: governments propose, markets dispose.” The breakdown of the international monetary system in the aftermath of Britain’s 1931 devaluation of sterling produced ongoing instability as speculators shifted from one currency to another in a doomed search for safety. Finally in 1936 the Tripartite Agreement introduced a bit of stability between the dollar, sterling and the franc, whereupon Charlie joined the New York Fed with the task of providing statistical support for the US role in the Agreement. This first taste of central banking continued in 1939 when he shifted to the Bank for International Settlements in Basel. His three year commitment however ended prematurely when Paris fell, and he returned to the US, now to the Board of Governors in DC. |

|

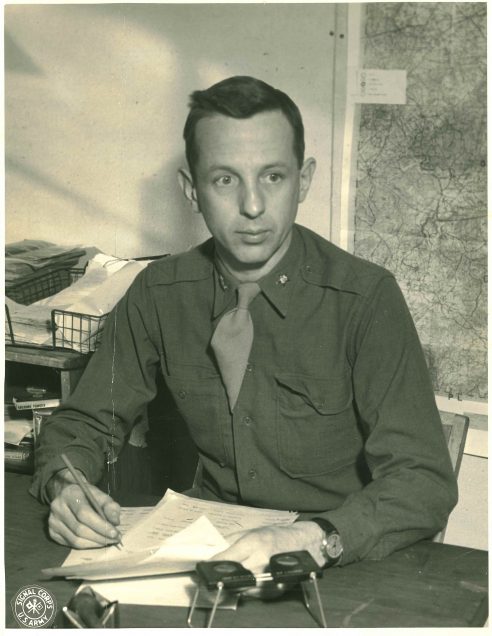

Ch. 4: A Good War“If one processes enough hay, one can find a few needles.” After working at the Fed with Alvin Hansen on postwar planning for the event of a possible German victory, Charlie joined the war himself as an intelligence officer for the Office of Strategic Services, stationed in London and then, after the successful D-Day landing, in the European theater, traveling with General Bradley. Grinding victory finally achieved, he shifted back home to the State Department and shifted his concern to postwar reconstruction, first in Germany and then in Europe more generally as the lead in drafting the Marshall Plan for Congressional approval. |

|

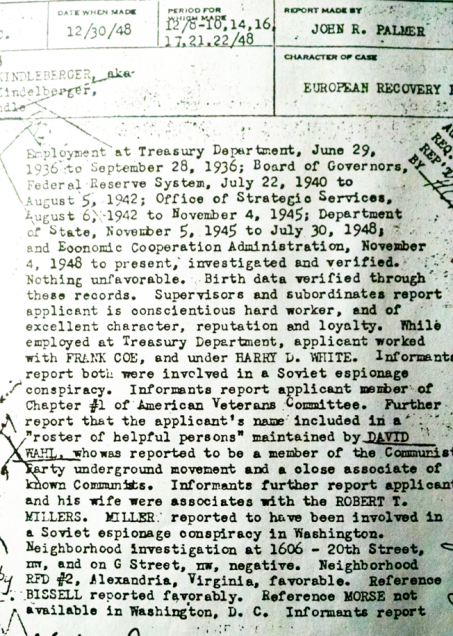

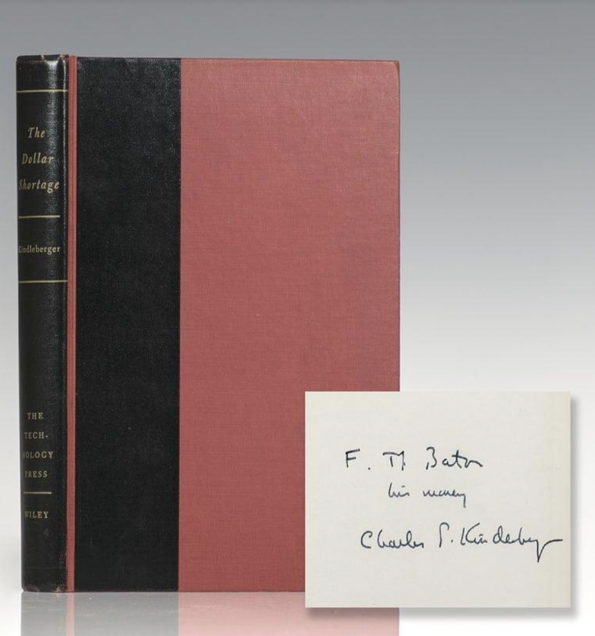

Ch. 5: Tech“A friend of mine was fond of enunciating, “What doesn’t kill, strengthens.” But that is not true either. Something that might not kill you might nevertheless leave you crippled.” Exhausted by his State Department gig, and anticipating Truman’s defeat, in 1948 Charlie made a shift to academia at MIT, where he would remain until 1981, shifting to half-time in 1976 after mandatory retirement at age 65. When security clearance troubles in 1951 blighted his original plan to keep a foot in the world of government policy, he turned to textbook writing for money and to economic history for material subject matter. Eventually, he got his clearance back, but by then the world had moved on, and Charlie found himself increasingly on the outside. His famous 1966 article for The Economist “The Dollar and World Liquidity: A Minority View” embraced that outsider status. |

|

Ch. 6: The Dollar System“The economically efficient system of a dollar standard may serve the cosmopolitan interest in a national frame. Its demands on world sophistication are excessive.” Instead of Charlie, it was Charlie’s contemporary Robert Triffin who captured the attention of the Kennedy administration, and so also of the economists who staffed that administration, including Charlie’s MIT colleagues. The papers in Charlie’s 1966 Europe and the Dollar trace his struggle against Triffinism, and the papers in his 1981 International Money trace his personal evolution from gloom, after Nixon’s precipitous devaluation of the dollar in 1971, to cautious optimism after Volcker guided the dollar back into the global system starting in 1979. |

|

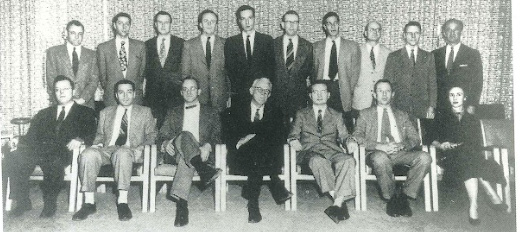

Ch. 7: Among Economists“In academic life, slow cooking works better than the microwave.” The embrace of floating exchange rates in the 1970s by economists both monetarist and Keynesian left Charlie once again in the minority, even as the work of Robert Mundell, Charlie’s sometime student, emerged as the dominant model that economists used to understand the new floating rate world. International monetarism, promoted by Harry Johnson, was his main target during these years. |

|

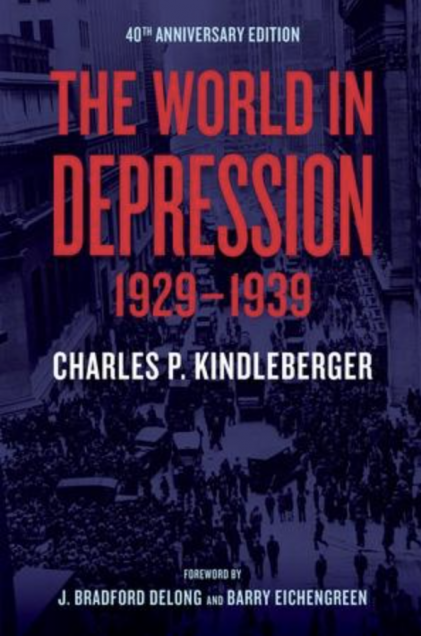

Ch. 8: Independence“Anything can happen and often does. The day of positive economics useful for prediction, is still some distance away.” Released from the duty of team loyalty by mandatory retirement in 1976, Charlie embarked on a third career as economic historian, starting with the best-selling Manias, Panics, and Crashes (1978) which built on and extended the argument of his earlier World in Depression (1973). Reading these books afresh, in the context of Charlie’s own intellectual formation and agenda, we can understand them as works of comparative political economy. |

|

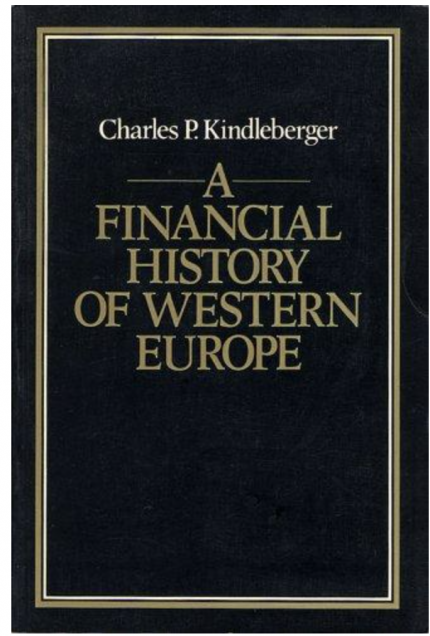

Ch. 9: Chef d’Oeuvre“A competent military officer is a generalist who can solve all kinds of problems.” In his 1991 autobiography, Charlie referred to his last big book A Financial History of Western Europe (1984) as his “chef d’oeuvre”. Reading this book afresh, in the context of all that came before, we can understand it as essentially Charlie’s treatise on money. The book tells a story of the Darwinian coevolution of an integrated world market with an international lender of last resort, the end result being a world market for commodities and also for capital, both short term and long term. |

|

Ch. 10: Leadership“Muddling through in Darwinian fashion is my preferred solution.” Honored by surprise election as President of the American Economic Association, Charlie organized the 1984 annual conference program and then gave the 1985 presidential address, more or less on the theme of money and empire, i.e. the challenge of providing the public good of international money in a world without international government. Shifting from his beloved Lincoln home to assisted living in Brookhaven, he continued watching the world and writing about it up to his death in 2003. |