Yu Gil-jun (1856-1914): A Bridge-Person of Korea to the West and the First Korean Student in the United States

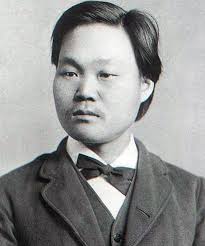

Yu Gil-jun was a Korean intellectual, writer, politician and reformist of the late Joseon Dynasty. Born in Hanseong (today’s Seoul) to a yangban family[1], Gil-jun adhered to the strict discipline of the Cheng-Zhu School (성리학 性理學), one of the major philosophical schools of neo-Confucianism. Although he excelled in his studies of neo-Confucianism, western culture and technology ultimately captured his interests. In 1871, when he was 16-year-old, Gil-jun became a student of Pak Kyu-su (1807-1877), a Joseon diplomat to China and a reformist. Gil-jun’s life changed when he saw a globe in his new teacher’s library and realized that the earth was round. After that incident, Gil-jun was fascinated with western studies, absorbing Pak’s reformist ideas. As Pak’s pupil, he became connected to a larger network, which included Pak Yeong-hyo, Kim Ok-kyun, Seo Gwang-beom, and others, who became leading figures in the Korean Patriotic Enlightenment Movement after the Japanese Annexation of Korea in 1910.[2]

Yu Gil-jun was a Korean intellectual, writer, politician and reformist of the late Joseon Dynasty. Born in Hanseong (today’s Seoul) to a yangban family[1], Gil-jun adhered to the strict discipline of the Cheng-Zhu School (성리학 性理學), one of the major philosophical schools of neo-Confucianism. Although he excelled in his studies of neo-Confucianism, western culture and technology ultimately captured his interests. In 1871, when he was 16-year-old, Gil-jun became a student of Pak Kyu-su (1807-1877), a Joseon diplomat to China and a reformist. Gil-jun’s life changed when he saw a globe in his new teacher’s library and realized that the earth was round. After that incident, Gil-jun was fascinated with western studies, absorbing Pak’s reformist ideas. As Pak’s pupil, he became connected to a larger network, which included Pak Yeong-hyo, Kim Ok-kyun, Seo Gwang-beom, and others, who became leading figures in the Korean Patriotic Enlightenment Movement after the Japanese Annexation of Korea in 1910.[2]

At the time, however, Korean politics were not focused on Japan, but on the fluctuations caused by the tension between conservatives and the reformists. The Joseon Dynasty’s prolonged policy of seclusion was challenged by an enlightenment movement, which offered foreign countries a good opportunity to enter Korea. In 1882, the Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce and Navigation was negotiated between the representatives of the United States and the Joseon regime of Korea.[3] Based on the Treaty, the first U.S. diplomatic envoy Lucius H. Foote arrived in Korea in May 1883. For his part, King Gojong of Korea dispatched Bobingsa (보빙사 報聘使), the first official Korean delegation to the United States in July 1883.

The official Korean delegation consisted of 10 members, led by the Chief Minister, Min Yeong-ik, Vice Minister Hong Yeong-sik, and Percival L. Lowell, who acted as the foreign secretary and counsellor.[4] By virtue of his international experience by studying at Keio University in Japan in 1881, Min Yeong-ik recommended Gil-jun be included among the 10 delegates sent to the United States. The Korean delegation arrived in New York on September 17, 1883, having travelled across the country from San Francisco. The next day they met the American President Chester A. Arthur at 11 o’clock in the morning.[5] Stopping in New York only to meet the President, the group travelled on to Boston. They spent a week in the city, visiting schools, companies, and industrial exhibitions, before leaving for Washington, D.C.

The third person from left in the second row is Yu Gil-jun.

After the completion of the diplomatic mission, Gil-jun petitioned the Chief Minister, Min Yeong-ik, to remain in the States in order to study mathematics and science. The Chief Minister approved and arranged for Gil-jun to receive a national scholarship for his study abroad, thereby making him the first Korean student in the United States.

Percival L. Lowell, the delegation’s foreign secretary and translator, was crucial in Gil-jun’s decision where to study. Lowell connected Gil-jun to his friend Edward Sylvester Morse (1838-1925), the director of the Peabody Academy of Science. As a matter of fact, Edward Morse and Yu Gil-jun were already known each other because Morse had lectured at Keio University in Japan as a professor of Biology when Gil-jun studied abroad there in 1881. Through the bridge of Lowell, they met again in Boston two years later.

Under the mentorship of Edward S. Morse, Gil-jun studied at the Governor Dummer Academy in Byfield, Massachusetts.[7] While at the Academy, Gil-jun exchanged letters with Morse and their correspondence continued even after Gil-jun returned to Korea. Their letters, along with Yu Gil-jun’s donation of his Korean clothing and accessories, which he had put aside in favor of Western dress during his stay in America, formed the core of the Peabody Essex Museum’s collection of Korean art and culture.[8]

Gil-jun felt English was difficult in school, but he was a passionate and smart student. A letter revealed that, “I am very happy to tell you about that, because it please you, and you are always anxious to see my improvement on my study. I have an examination yesterday afternoon, and get 87 percent that was 16 percent higher than anybody else and 13 percent less than hundred. Teachers, at first, told me that, they would excuse me for I do not take an examination because I am a newcomer and foreign born, moreover fresh student. So I answer them that I would and ought to have an examination like another student. Then they say ‘all right, and very glad to have you’ and I commence to feel anxiety so got to study somewhat a little harder than last week and fortunately make no mistake except one that I have not studied yet.”[9]

Some Korean news clips and Internet-based bibliographical sketches suggest that Gil-jun entered Boston University in the fall semester of 1884 after graduating from the Governor’s Academy. No such record, however, exists to confirm his attendance at Boston University.[10]

Yu Gil-jun’s studies in the United States could not be sustained very long. The political situation in Korea forced his return. The Gapsin Coup, a failed three-day coup d’état, resulted in the arrests of Gil-jun’s reformist friends and the Joseon government ceased giving him financial support. Thus, he suddenly had to go back to Korea. He wrote that “my homeward voyage is taken suddenly, rather unexpectedly, so I have no time to excuse my will, except the preparation of my journey, even so necessary as to pay you visit for bidding you a farewell.”[11] Once Gil-jun decided to go back to Korea, he took the European route instead of crossing the Pacific Ocean. From Boston he went to Japan via London, passing through the Suez Canal. It was a way to travel to diverse countries and see many new things.[12]

In the wake of the Gapsin Coup, pro-Chinese officials (Sugupa, 수구파 守舊派), the conservatives, took power over Joseon government, ruling from 1885 until 1894. When Yu Gil-jun arrived in Hanseong, he was accused of supporting the Gaehwadang (개화당 開化黨), the enlightenment party which had led the Gapsin Coup, and therefore was detained under house arrest from 1885 to 1894. After 1895, when the reformist (or some said, pro-Japanese officials) gained power, Gil-jun was appointed as the Vice Minister of State for the Home Office. In that role, he pushed for the modernization of Korea by reforming its governmental system.

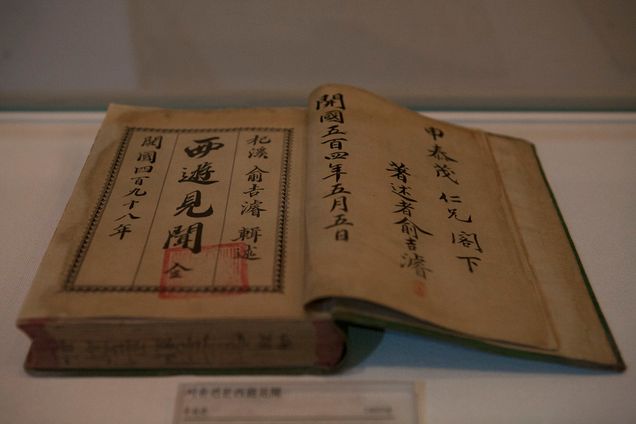

Yu Gil-jun’s experience in the greater Boston area was critical in fueling his enlightenment, or modernizing ideas. First, his experience gave him a good impression of Christianity. Though Gil-jun was an atheist, he thought that Christianity was the best religion. He believed it could teach Koreans something important, because Christians “never revolt to their government and always lived in a peaceful life.”[13] Second, he highly prized the importance of human equality that he heard emphasized in modernized societies. Based on his experiences of studying abroad in Japan and the United States, Gil-jun wrote several books and proposed ideas for political reform. While under house arrest he wrote Seoyu Gyeonmun (서유견문 西遊見聞), Observations on a Journey to the West. As one of the few Koreans who had traveled abroad in the nineteenth century, his book was one of the first works in Korean that described Europe and the United States. Consisting of twenty volumes in 556 pages, his book introduced the general outline of the global world, geographical information about Western countries, and the characteristics of major cities, including the monetary and education systems of each city. On top of that, it also introduced American and European perspectives on the concepts of sovereignty, independence, and equality. Using a combination of the Korean and Chinese characters to disseminate it to the wide audience, Yu Gil-jun especially emphasized the Western belief of the individual rights of all people regardless of their gender, age, or race. This idea was the basis of his conviction for the enlightenment of Korean society. He wrote that “enlightenment entails not only learning the advanced skills of others but also preserving what is good and admirable in one’s own society… a person who is insufficiently enlightened lacks judgment about the reality of the case due to his stubborn nature.”[14]

Yu Gil-jun’s experience in the greater Boston area was critical in fueling his enlightenment, or modernizing ideas. First, his experience gave him a good impression of Christianity. Though Gil-jun was an atheist, he thought that Christianity was the best religion. He believed it could teach Koreans something important, because Christians “never revolt to their government and always lived in a peaceful life.”[13] Second, he highly prized the importance of human equality that he heard emphasized in modernized societies. Based on his experiences of studying abroad in Japan and the United States, Gil-jun wrote several books and proposed ideas for political reform. While under house arrest he wrote Seoyu Gyeonmun (서유견문 西遊見聞), Observations on a Journey to the West. As one of the few Koreans who had traveled abroad in the nineteenth century, his book was one of the first works in Korean that described Europe and the United States. Consisting of twenty volumes in 556 pages, his book introduced the general outline of the global world, geographical information about Western countries, and the characteristics of major cities, including the monetary and education systems of each city. On top of that, it also introduced American and European perspectives on the concepts of sovereignty, independence, and equality. Using a combination of the Korean and Chinese characters to disseminate it to the wide audience, Yu Gil-jun especially emphasized the Western belief of the individual rights of all people regardless of their gender, age, or race. This idea was the basis of his conviction for the enlightenment of Korean society. He wrote that “enlightenment entails not only learning the advanced skills of others but also preserving what is good and admirable in one’s own society… a person who is insufficiently enlightened lacks judgment about the reality of the case due to his stubborn nature.”[14]

His efforts for the enlightenment of the nation blossomed through the Gapokyeongjang (갑오경장 甲午更張), the Gapo Revolution in 1894. The Korean government sponsored it as a reformation movement for the modernization of society. Through the Gapo Revolution, the Korean government initiated modernized systems in almost every part of society. It abolished the class system, replaced the lunar calendar with the Gregorian calendar, advocated the cutting of top-knots, modernized the military system, instituted a government-led immunization system, and the like.[15] Yu Gil-jun’s ideas of political reform played an important role in the revolution.

In a letter to Morse, Yu Gil-jun described his intentions:

- Clear distinction shall be drawn between Nation and Royal House.

- No distinction shall be mentioned between nobles and commons, in appointing to official positions.

- No taxes shall be taken without consent of the king and should be fixed by law about the rate and collector.

- No one shall be arrested and punished without an open trial.

- All the soldiers put together under one head.

- Primary School must be opened.

- The expenditure of the Royal House was fixed at a sum of $500,000 a year, preventing an unlawful squandering of national money by the royal family.

- The Rule of District must be published to the public, aiming to establish the constitutional country. [16]

Ultimately, the Japanese colonial regime exploited the reformers’ dream to modernize Korea. Japanese officials used the refromers’ call for Korea’s rapid modernization to justify their own expansion into the Korean peninsula. Yu Gil-jun, however, was not fooled. He opposed the Japanese annexation of Korea in 1910, and joined a movement against it. The Japanese colonial government tried to placate him by offering him a senior government office, but he refused it. Instead, he put his energy into the Korean Independence Movement. While an independence activist, Yu Gil-jun passed away in 1914 from heart disease. He was 58 years old.

By Gun Cheol Kim

[1] Yangban refers to the noble class of Joseon Dynasty.

[2] Dong-Chun Yu, Yu Kil-Chun Jeon [A bibliography of Yu Kil-Chun], Vol II (Seoul: Ilchogak, 1987), Chapter 1,2,3.

[3] John H. Haswell ed., Treaties and Conventions Concluded Between the United States of America Since July 4, 1776 (United States. Dept. of State, 1889), 216-221. The final draft was accepted at Chemulpo (today’s Inchon) in May 1884.

[4] Percival Lawrence Lowell (1885-1916) was an American businessman, mathematician, and astronomer. Born in Cambridge, MA, into the famous Lowell family of New England, he graduated Harvard University in 1876 majoring in mathematics. In the 1880s, Lowell traveled extensively through the Far East. During his two month stay in Japan, Lowell was approached to serve as a foreign secretary for the special Korean diplomatic mission to the U.S. For details, see Percival Lowell, Choson, the Land of Morning Calm: a Sketch of Korea (Boston: Ticknor and Company, 1888).

[5] “The Embassy From Corea”, The New York Times (September 18, 1883).

[6] Yu Kil-Chun to Edward Morse, December 3, 1896, Yu Kil-Chun Collection in the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.

[7] The Governor Dummer Academy (now the Governor’s Academy) was an independent boarding school for grades 9 to 12, 33 miles north of downtown Boston. The school was established in 1763 by the will of William Dummer (1677-1761) who had served as a governor of Massachusetts for many years. In order to advance to university, Kil-Chun had to pass secondary school.

[8] For details, see Yu Kil-Chun (1856-1914) and the Korean Collection at PEM (Peabody, MA: Peabody Essex Museum, 2009).

[9] Yu Kil-Chun to Morse, November 1884. All his letters were written in English.

[10] In a letter to Edward Morse written in January 28, 1885, Kil-Chun informed his friend that “the term of this school will be closed at the end of next March.” He finished the letter with “South Byfield, Mass,” not Boston. The school almost certainly referred to the Governor’s Academy. Furthermore, the Boston University Year Book of 1884 and 1885 does not have Yu Kil-Chun in its list of students.

[11] Yu Kil-Chun to Edward Morse, September 1885.

[12] Yu Kil-Chun to Edward Morse at the Port Said, October 8, 1885.

[13] Yu Kil-Chun to Edward Morse, September 1885.

[14] Yongho Choe et al., From Sources of Korean Tradition, Vol. 2: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Centuries (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 252.

[15] Top-knot was a Korean traditional hairstyle for married men.

[16] These are direct quotations from “The Reformation We Made,” in a letter to Morse, December 3, 1896.