Home

A Court that is Making a Difference

By Annemarie E. Hollenback in CJ 725

As a nation, we are making strides towards removing the stigma from mental illness. For many years, defendants in the criminal justice system were not afforded the same care or compassion. It became apparent that there was a need for an alternative to ‘traditional’ criminal court when it came to individuals dealing with mental illness. In response to this, mental health courts have begun to emerge in response to the inability of jails to treat properly and effectively those with mental illness. Their goal is to rehabilitate and treat the offender for their illness, as opposed to using punishment as the only deterrent. Punishing someone for their crime without treating the mental illness that led them to that behavior leaves the offender facing a high percentage of recidivism in their future.

There have been mental health courts in existence for over 20 years. However, in the beginning, not every offender had access to one. They were not in every state or every jurisdiction. As time has gone on, they are becoming more and more prevalent thanks in large part to the criminal justice professionals who recognized a need for this alternative to conventional court for this segment of the population.

The first mental health court in New York City was the Brooklyn Mental Health Court (BMHC). In existence since 2002, when this approach to mental health care vs. incarceration was still a somewhat new idea, the BMHC began to see defendants (called ‘clients’) in their courtroom. There was an approach towards treating the whole person. According to the presiding judge, Matthew D, Erric, defendants with mental health issues had two choices facing them after arrest – they could plead insanity or go to trial/enter a guilty plea and go to prison. Mental health courts provided the defendants with a third option – come to court and agree to treatment. By admitting their mental condition played a part in the commission of their crime, they would receive treatment for their illness and be offered the chance at rehabilitation and a more positive outcome at the end of their treatment program. The participants are still held accountable for their actions but instead of incarceration, they receive appropriate long-term treatment and community-based support.

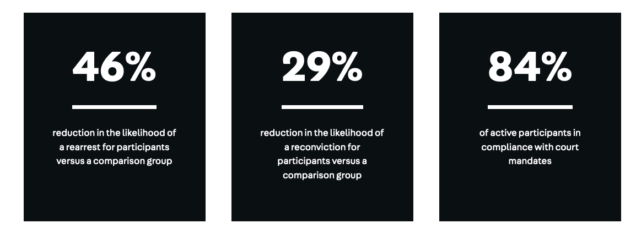

One of the basic tenents of the BMHC is to treat all clients with respect and dignity, seeing them as individuals with problems that can be addressed within the community as opposed to languishing in prisons. It’s a successful model, boasting the following statistics.

One of the goals of the BMHC is to reduce hospitalizations/arrests and help the clients achieve and maintain psychiatric stability. Not only does the client benefit from this, but this gives their families (spouses, children, etc.) a sense of hope that they would not have if their family member was incarcerated and not receiving any treatment. By diverting clients into treatment vs. prison, the whole family benefits and can heal.

Accountability towards the program is achieved through rewards for positive achievements and sanctions for setbacks. The client is motivated to comply with their treatment plan and treatment plans are tailored to help the client maintain a sense of stability. There is regular monitoring of not only the progress of the client but also the agencies/service providers who are a part of the treatment plan.

As part of the treatment program, the client receives help with health care issues, homelessness, life skills, job searches and they are provided with the tools to become and remain successful outside of the program. The BMHC works with many government and non-profit service providers to address these needs. Instead of serving time and being released, the clients of the BMHC ‘graduate’ from the program. Just the use of the word ‘graduate’ implies they have achieved something in their life. It leaves them with a positive outlook moving forward as well as a feeling of accomplishment. Successful outcomes can result in the client having their criminal charges dismissed or reduced.

The following video offers a glimpse into the BMHC – its mission, its compassion, as well introducing the viewer to some successful graduates of the program.

A successful mental health court can help reduce overcrowding in prisons, reduce the percentage of recidivism and change lives. It provides access to mental health treatment to those who lack the proper insurance to seek treatment. At the time the above documentary was made (2019) the BMHC was celebrating the graduation of the thousandth client from their program. That is no small feat.

The Brooklyn Mental Health Court serves as a model for other mental health courts. They are striving to not only remove the stigma from mental illness but to treat those who are struggling with compassion, dignity, and a desire to help improve lives for both the clients and their families.

Resources:

“Mental Health Courts” in Slate, R.N., & Johnson, W. W. (2008). The criminalization of mental illness. Carolina Academic Press

Center for Justice Innovation: Brooklyn Mental Health Court. https://www.innovatingjustice.org/programs/brooklyn-mental-health-court

YouTube. (2019). Transforming Lives: The Brooklyn Mental Health Court. YouTube. Retrieved February 27, 2023 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IB42mdkOXCs

Learning Theories

As I have mentioned before, Learning theories have always been my favorite ones to understand crime. Not only can they explain crime, but they also leave the door open to change. I wanted to extend our discussion about theories and put together some research that I have previously done on learning theories. "A scientific theory of crime should provide a general explanation that encompasses and systematically connects many different social, economic, and psychological variables to criminal behavior" (Bartol & Bartol, 2021. p, 4).

Sutherland's Differential Association Theory (DAT) states that behavior is learned through interactions while communicating with our closest groups. Sutherland's DAT has nine principles (Cullen et al. 2018):

- Criminal behavior is learned.

- Criminal behavior is learned through our communication processes.

- Criminal behavior is learned from our intimate groups.

- Learning criminal behavior involves techniques and the motives to commit a crime.

- The legal code is seen as favorable or unfavorable, which is how motives to commit criminal behavior are learned.

- A person becomes a criminal when the consequences of violating the law are more favorable than unfavorable.

- Differential association varies in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity.

- Learning criminal behavior entails the same ways in which we learn any other type of behavior.

- Criminal behavior is not excused by general needs and values.

Aker's Social Learning theory (SLT) states that behavior is learned and reinforced by those groups closest to us through instrumental conditioning. There are four significant concepts (Cullen et. al 2018. p, 81):

- Differential association: the primary groups we associate with expose us to definitions and models to imitate.

- Definitions: are the meanings we give to behavior.

- Imitation: This is engaging in behavior after seeing others.

- Differential reinforcement is the balance of rewards and punishments, depending if we see them as positive or negative.

A study by John K. Cochran, Jon Maskaly, Shayne Jones, and Christine S. Sellers (2017), Using Structural Equations to Model Aker’s Social Learning Theory With Data on Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). The study included people that were in a relationship or had a relationship before. The results in both models proved that SLT could explain IPV in prior and current partners, especially the variables for differential reinforcement, definitions, and imitations. Akers's Social Learning theory has proven to be true when tested and has also shown that it is a general theory that can explain different types of crimes.

The code of the street by Elijah Anderson. “The code of the street is a set of informal rules governing interpersonal public behavior, particularly violence. The rules prescribe proper comportment and the proper way to respond if challenged” (Anderson, 2000. Pag. 33). The code has existed for years in different forms through different civilizations, but it has always been there. The perpetuation of the code continues in those societies that are often at a disadvantage. We can see street and descent families and how the children are influenced and learn from those around them.

Learning theories explain how people can learn criminal behavior from those around them. But they can also explain why people change or do not commit criminal acts when they are not accepted or committed by those closest to us. Specific theories can explain some crimes better than others. For example, developmental and trait theories can explain life-course-persistent offenders and adolescent-limited offenders. But, intersectionality between theories exists, and it helps to understand crime better and to put more pieces together, as there is not only one reason why crime happens. Regarding learning theories, nature vs. nurture and strains are essential to remember.

References:

Anderson, E. (2000). The code of the street. Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. Norton & Company Inc.

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2021). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach (12th ed.). Pearson.

Cochran, J. K., Maskaly, J., Jones, S., & Sellers, C. S. (2017). Using Structural Equations to Model Akers’ Social Learning Theory With Data on Intimate Partner Violence. Crime & Delinquency, 63(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128715597694

Cullen, F. T., Agnew, R., & Wilcox, P. (2017). Criminological Theory: Past to Present. 6th edition. Oxford University Press.

Geographic Profiling for No-Body Homicides

Investigative psychology, or more commonly known as profiling, has become very popular in recent years due to popular TV series like Criminal Minds (Bartol and Bartol, 2021). The basis behind investigative psychology, coined by David Canter, involves the application of psychological research and principles to the investigation of criminal behavior (Bartol and Bartol, 2021). Our textbook breaks down profiling into five categories, one of which is geographical profiling (Bartol and Bartol, 2021). Bartol and Bartol (2021) describe geographical profiling as a technique used to help locate geographical locations related to a serial offender’s residence or base of operations as well as where the next crime by this perpetrator may take place. This process tends to be highly actuarial and generally involves sophisticated computer software programs, like Criminal Geographic Targeting Program (CGT), Crimestat, or Dragnet, that apply statistical probabilities to areas that seem to fall within the perpetrator’s territory based on their known movement patterns, comfort zones, victim-searching patterns, and the location of the previous crimes (Bartol and Bartol, 2021). Although geographic profiling does not lend to the demographic, motivational, and psychological features of the crime or the perpetrator, it focuses more on how the location of the crime relates to the residence and/or base of operations for unknown offenders of both violent crimes and property crimes (Bartol and Bartol, 2021).

Another form of geographical profiling that was not mentioned in our textbook was brought to my attention about a year ago and it involves the inverse process of what is described above – instead of finding the offender, it focuses on finding undiscovered clandestine graves, body dumps, or scattered remains when the offender is known or still at large but their behavior has revealed a pattern (Moses, 2019). For no-body homicides, or cases in which the victim is suspected to be deceased, but their remains have not been located, with known offenders, investigators can gather all the areas the perpetrator is familiar with, their personality preferences, and risk factors, like risk of being discovered when disposing a body, to try to narrow down where the body may be located (Just Science, 2022). This type of profiling is very important to the field because it helps to allocate resources appropriately, converge manpower on areas that have the highest chance of reaping success, and increases the odds of proper prosecution (Just Science, 2022).

This type of profiling is primarily actuarial and based on statistics, or base rates, gathered by the FBI regarding body disposal (Bartol and Bartol, 2021; Just Science, 2022). For example, people who kill their own children or close family members (not including spouses) often dump the bodies in a one to five mile radius from the home where they were likely killed (Just Science, 2022). This is evident in the death of Caylee Anthony, where her remains were found in a wooded area close to the family home prosecution (Just Science, 2022). In cases where the victim is an intimate partner or spouse, the offender will likely move the body further away, usually 30 miles or more from where they were killed (Just Science, 2022). This is evident in the death of Laci Peterson and her unborn child, where they were dumped in the San Francisco Bay about 90 miles from their home (Just Science, 2022). If the victim was a friend or acquaintance, they are usually found within a radius of ten miles from where they were killed (Just Science, 2022). Additionally, if the victim was a stranger, they may be found closer to the offender’s known area than an acquaintance, but the offender may not try to hide the body, whereas for acquaintances and friends they might (Just Science, 2022).

With humans, sometimes their motivations may vary. For example, some people may try to hide the body so it won’t be found, while others, like serial killers, may want the body in a place where it will be found fairly quickly or in a place where they can return to it easily (Just Science, 2021). Additionally, distance is understood differently among different groups of people (Just Science, 2022). For example, people who live in rural areas travel long distances without a lot of traffic to conduct business, so their perception of distance may be quite different than someone who lives in a metropolitan area (Just Science, 2022). Lastly, in spur of the moment type homicides, the offenders may leave the body where they are or make a haphazard attempt to move it (Just Science, 2022). These differences in perceptions, personality, and motivations are calculated into geographic profiling, so inconvenient areas can be excluded (Just Science, 2022).

If you’re interested in learning more, I interviewed Dr. Sharon Moses in a Just Science podcast episode about this topic here: https://forensiccoe.org/podcast-2022casestudies-part1-ep3/.

References:

Bartol, A. and Bartol, C. (2021). Criminal Behavior: A Psychological Approach. (12th Edition). Pearson.

Moses, S. K. (2019). Forensic Archaeology and the Question of Using Geographic Profiling Methods Such as “Winthropping”. In Forensic Archaeology: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 235-244). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03291-3_15.

Just Science. (2022). Just Forensic Archaeology and Body Dump Sites. Forensic Technology Center of Excellence. https://forensiccoe.org/podcast-2022casestudies-part1-ep3/.

Police Officer Suicide and Suicide Prevention

Tony Ford

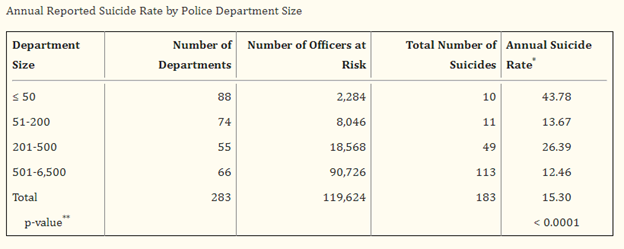

It is a sad fact that police officers are more likely to die from suicide than in the line of duty. In 2020, 116 police officers died by suicide while 113 died in the line of duty (Stanton, 2022). In 2021, that number rose to 150 officers dying by suicide (Leone, 2022). Tragically, law enforcement officers have a 54% increase in suicide risk when compared to the civilian population (McAward, 2022). The problem seems to be even worse in smaller departments, which may not have an extensive support system or peer support resources. A 2012 study published in the International Journal of Emergency Mental Health found that departments with less than 50 full-time officers had a suicide rate over triple that of departments that had over 500 full-time officers (Volanti, et.al, 2012). This is concerning, as 49% of the police departments in the United States employ less than 10 full-time officers (Volanti, et.al, 2012).

Figure 1 Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine. Figures are per 1,000 officers.

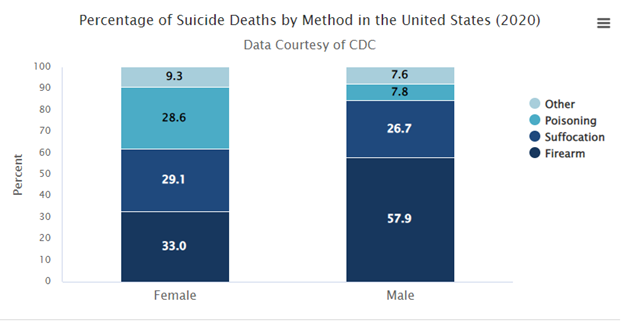

In the United States, most suicide attempts among the general population are not fatal (McAward, 2022). Yet, when a firearm is used, the chances of a suicide attempt becoming fatal skyrocket. Suicides that involve a firearm have a fatality rate greater than 82% (McAward, 2022). Police officers nearly always have a firearm available. In fact, the majority of law enforcement suicides happen at home, using the officer's own service weapon (McAward, 2022).

Figure 2 Data courtesy of the CDC

Though more study is needed, the lower suicide rate in larger departments may indicate that many of the mental health and peer support programs in use are having a beneficial effect. My department, which is over 500 sworn officers, has a robust peer support system that has officer volunteers. These volunteers go out to officer-involved shootings to offer support for officers that may need them. In addition, in 2021 we hired an on-staff clinician. She also comes out to deadly-force incidents and is available to speak with the officers. No officer is forced to take advantage of either resource, but they are there if needed. The peer support system has become more robust over time, with more and more offices volunteering to serve in the program. The clinician is also available for counseling services, and officers may go for a session either on or off duty. They do not have to involve their chain of command in the scheduling, and the clinician provides nothing other than a work excuse note. The clinician will also likely become more effective as she spends time with officers and learns the stressors of the job. The support is welcome, as we have lost three officers to suicide since I started in 2002.

There are other things departments can do for suicide prevention. John Becker, a former police officer turned clinician in Pennsylvania, recommends programs for positive stress relief, such as softball, basketball, or bowling leagues (Becker, 2016). He also says that supervisors have a role to play in ensuring open communication (Becker, 2016). Support, he says, doesn’t have to be a group hug. Simply asking a subordinate how their shift went that day would encourage communication (Becker, 2016). He also points out the numerous benefits of better mental well-being in a police force, benefits that extend beyond suicide prevention (Becker, 2016). A healthy department will have fewer complaints and lawsuits, fewer officers calling in sick, fewer grievances and resignations, and even fewer on-the-job injuries (Becker, 2016).

There is no field quite like policing. The higher occurrence of suicides in the field should be met with programs and professionals who understand what officers are going through. Many times the best professionals for that task are other police officers. Departments should strive to have a holistic approach to officers' mental well-being, and show officers that they care about their mental health. A department that ignores this important aspect of employee care is doing a disservice to their officers and the public that they serve.

Juvenile Delinquency and Mental Illness

Many times, juvenile delinquency is dismissed as just troubled teen behavior until it increases to more serious crimes. For most of these juveniles, however, there are many factors that lead to delinquent or criminal behavior. In fact, almost 70% of juveniles that commit criminal behavior have at least one diagnosable mental illness (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2017). Many of these disorders include anxiety or depressive disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, conduct disorders, or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Within the population of juveniles that have one of these or other diagnosable mental health disorders, more than 60% have been shown to also have substance use disorders at their young age (Rousseau, 2023). This means that there is not only a need for mental health services within juvenile justice populations, but also a need for addiction screening and treatment services. Currently, our criminal justice system does not have enough evidence-based and trauma-informed resources for adult or juvenile services within the general or carceral populations. There needs to be a higher focus on these services for both adult and juvenile populations, but especially within juvenile settings at first signs of antisocial or delinquent behavior to help prevent future criminal or violent behaviors. This can be accomplished through further application of trauma-informed and evidence-based practices in schools and in juvenile diversion programs.

One such strategy deploys day treatment programs rather than incarceration. This allows the juvenile to be treated for mental health disorders, substance addictions, and remain in their familiar home environments rather than have to experience incarceration at an early age or leave their support systems, and are only incarcerated if they fail to meet the requirements for attending and participating in the community program (Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. ). Another important factor in both juvenile delinquency and mental health disorders is the family system and environment. For juvenile offenders that have serious crimes or behaviors, there are certain therapy approaches that are used to be able to address these concerns. One is Multisystemic Therapy (MST) that focuses on the whole picture of factors, including the family unit, peer groups, neighborhood, and school performance (Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. ). Another similar therapy method is Functional Family Therapy (FFT) while focuses specifically on the family unit and setting to identify the strengths and resilience of the family members, especially the juvenile (Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. ).

There are many risk factors that can be present in a child's life that can lead to either mental illness, antisocial or criminal behaviors, or both. Patterson's Coercion Developmental Theory discusses some of these particular psychosocial factors that can lead to early delinquent behaviors that are typically followed by more serious criminal acts in juveniles. These include poor parental monitoring, inconsistent parental discipline, abusive household, and disruptive family transitions, such as multiple moves to new places or divorce (Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. 186). Since these risk factors, along with other factors in the individual's neighborhood and school settings, provide a high correlation to juvenile offenders and also mental health disorders, it is important that schools and family units are able to provide correct resources and programs for juveniles to prevent possible criminal behavior. Juvenile programs to prevent delinquency and criminal behavior are characterized by several factors that are based in research for a successful outcome. The programs have to begin early, with behavioral screening and treatment for aggressive, disruptive, or noncompliant behaviors as early as age 4 or 5 for children who display antisocial tendencies at an early age. They also have to take into consideration differences in gender between juvenile offenders, and implement gender-specific programming. These preventative programs must focus on the family unit and parental support, abuse, monitoring, and other factors within the household first, then on the behavior with peers, teachers, authority, and friends (Rousseau, 2023). These preventative programs for signs of juvenile antisocial behavior, if implemented correctly, can screen for mental health issues and signs of potential substance reliance before it turns into criminal acts or substance abuse.

Once a juvenile offender is involved in the criminal justice system, the focus needs to be on rehabilitation and treatment, not punishment. The first step is consistency in screening and treatment referrals. Case studies have shown that different jurisdictions have different procedures for when youths are evaluated for mental illnesses and when they are referred for treatment, with some starting at intake by police, some at holding awaiting court, and some after court once appointed by the judge (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2017). There are also then factors of if treatment is offered and how effective the treatment is based on where the individual is placed, whether it is a juvenile correctional facility, a residential setting, detention center, community program, or outpatient program. With differences in the availability of treatments and access based on not only the jurisdiction, but also the type of facility that individual is held in, research has shown that those inconsistencies can easily lead to higher likelihoods of mental illness symptoms while in custody as well as higher recidivism rates once released if not properly treated while incarcerated, due to the increased risk factors for both mental health disorder symptoms and overall behavioral patterns in potentially overcrowded and mentally challenging environments of correctional facilities for juveniles (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2017). This is why juvenile mental health issues, along with trauma-informed screening and treatment programs for juvenile antisocial behavior, are incredibly important to implement with more accessibility and prevalence in order to prevent delinquent or criminal actions through assessment and treatment of mental health issues along with family and environmental risk factors in a juveniles' life.

References:

Bartol, A. & Bartol, C. (2021) Criminal Behavior: A Psychological Approach. (12th Edition). Pearson.

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2017).

Juvenile Diversion: Can these programs be improved?

The current trends in juvenile crime and addiction appear to have skyrocketed and the capabilities of the diversion programs seem to be struggling to keep up. This is similar in many ways to the struggles law enforcement is having in prevention efforts with juveniles. Many of the relevant studies that were completed are outdated and do not carry current information on juvenile delinquency as it pertains to addiction and crime. Unfortunately, the U.S. is in the midst of an opioid epidemic where easy access to drugs can be found on social media, through social groups and in schools. I share this insight from 18 years of law enforcement experience and personal observations.

The purpose behind juvenile diversion is to provide an opportunity to move juvenile offenders away from formal judicial processes. Some of these programs are offered prior to entering the judicial process while others are offered following adjudication or an admission of guilt (2017) In the later portion of entering diversion these efforts are considered in lieu of detention or incarceration in hopes that diverting the juvenile to a program will assist in prevent further criminogenic behavior and deeper penetration in the juvenile justice system (2017).

In an article by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, they provided two relevant theoretical perspectives that can be utilized to justify the purpose of diversion. The first being “labeling theory, which contends that processing certain youths through the juvenile justice system may do more harm than good, because it inadvertently stigmatizes and ostracizes them for having committed relatively minor acts that may have been more appropriately handled outside the formal system” (2017). The second perspective is “differential association theory that suggests that system involved youths will adopt antisocial attitudes and behaviors from their delinquent peers. Exposure to and fraternization with more advanced delinquent youths and adults is thought to have a criminogenic effect that increases the probability of youths reoffending” (2017).

When taking these two perspectives into consideration it becomes imperative for the juvenile criminal justice system to continue to pursue prevention and early intervention through a variety of diversion programs. It is also important to understand that research is showing that the most cost-effective place to stop recidivism among juveniles is as early as possible (Youth.gov, 2000). A brief from the National Conference of State Legislature advises that it costs approximately $588.00 a day to keep a juvenile incarcerated where diversion programs typically cost $75.00 a day (Diversion in the Juvenile Justice System, n.d.). Cost cannot be the only driving factor, but if funding could be directed towards programs that work to prevent recidivism it would be more beneficial to everyone involved in the juvenile system.

When taking all of that into consideration, diversion is the obvious direction to take, but should the juvenile system take into account that youth are becoming more involved in dangerous behavior like auto theft and robbery. I believe diversion can still work with juveniles involved in more dangerous behavior to move them away from continued criminal behavior. A lot of this can start in the schools by providing programs like social competence, conflict resolution, violence prevention, social competence and mentoring programs to teach juveniles that their social dynamic does not define them (Youth.gov, 2000). Besides programs that can be provided in schools or for minor offenses I believe the diversion programs should include intensive programs for repeat offenders that are not a safety risk for the community. As an example, a juvenile who has been arrested multiple times for auto theft could be entered into an intensive program to work towards reducing future recidivism.

One issue that has been identified is the lack of consistency among diversion programs and that every state has a different approach to how diversion is utilized. This includes when diversion takes place, who decides eligibility of diversion, if services will be provided, if a juvenile must admit guilt before being admitted to a program and if sanctions can be imposed for failing to complete diversion (Foundation, 2020). Some argue that imposing sanctions for violated rules is counterproductive to the diversion process and results in a formal delinquency record (Foundation, 2020). I would argue that diversion needs to have consequences associated with failing a program. I don’t know if that means they receive the full punishment for the offense they committed or if it should increase the intensity of the program, they are a part of, but we cannot just expect them to complete a program without an incentive.

Equity is another issue that has come up regarding diversion. How does the diversion process ensure consistent equity among offenders selected for a program? In an article by the Annie E. Casey Foundation minorities are given diversion much less than their white counterparts (Foundation, 2020). There are policies in place that should maintain that equity, but due to the way diversion is decided by individual decision makers this disparity seems to be prevalent starting in the selection process (Foundation, 2020). This is one area having consistent regulations can assist in promoting racial equity. The offense should play a greater role in the juvenile system when it comes to diversion and more attention should be given to offenders and their individual needs. This could easily be accomplished by the use of assessments similar to what is used during entry into probation.

Ultimately, there is no argument that diversion has its purpose and can be a very effective tool, but improvement is needed in the selection and compliance processes. More effort should be placed on understanding a juvenile offender's specific needs and the diversion program providing subjects that will help offenders succeed. I don’t know if there is a perfect answer, but diversion programs should include mental health assistance, and addiction treatment along with the current available programs. Diversion has to adjust to the current juvenile culture and find ways to not only succeed with juveniles who commit minor offenses, but also include the juveniles who have a more significant history as long as they do not present a risk to society. I firmly believe that no juvenile is completely lost to a life of crime and law enforcement, policy and law makers along with the judicial system can work together to save as many juveniles as possible.

Resources:

(2017, February). Diversion from Formal Juvenile Court Processing [Review of Diversion from Formal Juvenile Court Processing]. Https://Ojjdp.ojp.gov/. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/model-programs-guide/literature-reviews/diversion_from_formal_juvenile_court_processing.pdf

Diversion in the Juvenile Justice System. (n.d.). Www.ncsl.org. https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/diversion-in-the-juvenile-justice-system

Foundation, T. A. E. C. (2020, October 23). What Is Juvenile Diversion? The Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://www.aecf.org/blog/what-is-juvenile-diversion#:~:text=Does%20juvenile%20diversion%20work%3F

Youth.gov. (2000). Prevention & Early Intervention | Youth.gov. Youth.gov. https://youth.gov/youth-topics/juvenile-justice/prevention-and-early-intervention

Appropriate Response to Evaluating and Treating Trauma in Incarcerated Women:

The percent of incarcerated women has skyrocketed by 750% from 1980 to 2017 (Park, 2022). Women have grown as prison population, however, the profile of a female offender is significantly different than that of a male. Specifically, most female inmates have experienced some form of trauma prior to their time in the facility. In addition, the prevalence of PTSD is at 53% for incarcerated women in comparison to 10% in the general population. Further, female offenders are more likely to have experienced sexual violence and/or victimization both prior to their time in the facility, as well as, within the correctional establishment. Women represent 22% of assaults imposed by other incarcerated persons and 33% of assaults imposed by staff in state and federal prisons (Heidi, 2022).

In addition, many young girls in jails report physical and sexual assault prior to getting arrested and engaging in prostitution and living on the streets in an attempt to escape violent interpersonal interactions (Cowan, 2019). Altogether, it is apparent that trauma in the form of physical and/or sexual abuse is not only prevalent as a mental health issue in female prison populations, but may be a significant contributing cause to criminal behavior (Rousseau, 2023). Therefore, it is imperative to address trauma within correctional settings not only as a means of mental health rehabilitation but also a remedy for recidivism.

Although many institutions are lacking adequate resources to combat the issue of trauma, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration identifies the following pillars in combating the issue of trauma; peer support, collaboration and mutuality, empowerment voice and choice, physical and psychological safety, trustworthiness and transparency, and cultural, historical, and gender issues. In addition, many departments of corrections (DOC) leaders have adopted evaluation strategies to properly assign inmates to appropriate treatment strategies. Some of the assessment tools include; Womens’ Risk and Needs Assessment, Service Planning Instrument for Women, and Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions. These efforts attempt to deal directly with the topic of trauma in an attempt to provide adequate interventions for women in need. Lastly, institutions that have recognized the issue and impact of trauma on mental health and rate of crime in female populations have provided the staff with training, policies, and procedures to recognize and approach trauma-based behaviors in an evidence-based manner (Park, 2022).

Heidi. (2022). Women in prison suffer trauma before and during incarceration. Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://www.endfmrnow.org/trauma-and-women-in-prison#:~:text=Trauma%20and%20Women%20in%20Prison&text=Incarcerated%20women%20have%20histories%20of,and%20post%20traumatic%20stress%20disorder.

Park, Y., & About the author Yunsoo Park. (2022, March 11). Addressing trauma in women's prisons. National Institute of Justice. Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/addressing-trauma-womens-prisons

Cowan, B. A. (2019, April). Incarcerated women: Poverty, trauma and unmet need. American Psychological Association. Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/indicator/2019/04/incarcerated-women

Rousseau, D. (2023). Module 4: All Pages. Black Board. Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://learn.bu.edu/bbcswebdav/courses/23sprgmetcj725_o1/course/w3/metcj725_ALL_W3.html

War on Drugs

Lyly Mai

February 26, 2023

MET CJ 752 O1 Forensic Behavior Analysis.

Blog Post - War on Drugs

The war on drugs within the United States became prevalent leading up to the 1970s. Since then President Richard Nixon decided to declare war against drugs to eradicate the illegal use of drugs. In the following decades, there have been military and police teams dedicated to fighting this war. In 1971, Nixon tells Congress that, "If we cannot destroy the drug menace in America, then it will surely in time destroy us." After saying this, it was like Nixon had predicted the outcome of how dire this situation would entail and the results would be deemed catastrophic if not dealt with. The drug war led to many other consequences that led to violence around the world.

Here are a few impacts that affected the U.S. negatively:

- mass drug offense incarcerations

- proliferated violence

- Smuggling/illegal trading

- overdoses/drug-related deaths

Although you can crackdown on drug use on one area, because of the market is prevalent for making profit on selling drugs, another area will certainly pop up to take its place instantly. Someone else will take up the job to manufacture and distribute somewhere else. The U.S. had put in over $1 trillion to the war on drugs thus far. But nothing has made a serious dent on improving the conditions. The results were but failures to improve on the four impacts stated above. Many drug policy experts attempted to call for reforms. Some of these reforms to appease the conditions are as follow:

- focus on rehabilitation programs

- decriminalization of some illicit substances

- legalization of certain drugs

In 1973 and then again in 1977, eleven states took the initiative to decriminalize marijuana possession. However in the 1980s, during the Ronald Reagan presidency period the rate of incarceration for drugs drastically increased by tenfold. The number of people who were arrested and incarcerated during this time period went from 50,000 to 400,000 from 1980 to 1997. Everywhere around the word, the prisons and jails were overcrowded with inmates in for this offense. This led to another huge problem within the prison system. There weren't enough beds and housing to place these inmates. Violence increased, tension amongst the prisoners and toward the officers increased in hostility.

According the to text, in 2010 there were nearly 8 million individuals who needed to be treated for illicit drug use. However only 1.5 million people actually received the necessary treatment at a facility for drug use. It was stated that about 65% of inmates are addicted or currently abusing drugs. On top of that, in 2010 65% of inmates had met the criteria for substance abuse. That's an alarming percentage of the population of inmates. Some possible solutions could be:

- Dealing with the drug crisis in the prison sentence; crackdown on drug users, heavier penalties on those dealing drugs in prison

- Rehabilitating those inmates who are currently addicted to drugs

- Counseling/Therapy

- Courses on life skills in order to work their way back into society

Resources

Rousseau, 2023. Module 2.

Lopez, G. (2016, May 8). The War on Drugs, explained. Vox. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.vox.com/2016/5/8/18089368/war-on-drugs-marijuana-cocaine-heroin-meth

A history of the Drug War. Drug Policy Alliance. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://drugpolicy.org/issues/brief-history-drug-war

Trauma in Law Enforcement Professionals

Joshua Hoskins

Blog Post

CJ725

How to Support Law Enforcement Professionals That Deals with Distressing Material

Law Enforcement professionals are often exposed to terrible atrocities. Whether it be a dead body, child pornography, vehicular accidents, etc., law enforcement professions are often exposed to secondary trauma (Denk-Florea et al. 2020).

Researchers stationed in the United Kingdom expanded on the research into the effects of secondary trauma on law enforcement professionals. They interviewed and studied 22 law enforcement professionals on how they felt and coped (Denk-Florea et al. 2020). Additionally, they discussed the personal strategies these individuals attempt to mitigate the high chances of falling into disassociation mindsets.

The researchers primarily concentrated on the effects of child pornography on the mental fortetitude of the law enforcement profession. What they discovered was that over time was that they were becoming apathetic towards the material they were viewing (Denk-Florea et al. 2020). The researchers discovered there existed an increase need for mediation in the field to better develop recilient law enforcement professionals (Denk-Florea et al. 2020). In conjunction with apathetic mindset, burnout was an increase risk factor for most of the test subjects.

The subjects discussed their personal approaches to selfcare and what helped them before they had to view the material. Some discussed they mentally prepared; while others felt better after talking to a trained professional or a close friend about the incident (Denk-Florea et al. 2020).

When asked what the subjects wished to see for improvement, they wanted an increased in supervision involvement, better psychological help, and other methods to build resiliency. (Denk-Florea et al. 2020).

The study was thorough and a quick read. It shone light on different methods to mitigate risks for mental health issues within law enforcement personnel. It was interesting to see that other countries had similar issues to that of the U.S.A when it regards secondary trauma for our first responders.

References:

Denk-Florea C-B, Gancz B, Gomoiu A, Ingram M, Moreton R, Pollick F (2020) Understanding and supporting law enforcement professionals working with distressing material: Findings from a qualitative study. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0242808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242808

Trauma in Female Juvenile Inmates and Delinquents

Yasmin Sobrinho

February 26, 2023

MET CJ 752 O1 Forensic Behavior Analysis.

Blog Post

For my blog post I am going to discuss trauma in juvenile inmates, more specifically, female juvenile inmates. In module 4 of the course, we discussed female inmates and how treatment differs from males to females in the prison system. I mentioned in the discussion board for Module 4 that effective treatment for female inmates is unique because policy makers need to consider several factors: “mental illness, trauma, substance abuse, and relationship issues” (Rousseau 2021). The same applies to female juvenile involved in the justice system. According to Bartol & Bartol (2020), “justice-involved girls have been shown to have higher rates of trauma, more mood disorders, and sometimes more substance misuse than justice-involved boys” pp. 176). As most research and statistics has supported, there is a disparity among gender in our criminal justice system. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons (2021), there is a major gender imbalance in our system, with females accounting for only 7% of inmates and males 93%.

I came across a study by Salisbury & Van Voorhis (2009), which highlights the difficulties women face that cause them to offend: unhealthy relationships, trauma, mental illness, and substance abuse. The first pathway based on childhood victimization showed that child abuse does not directly affect women’s recidivism, but it did indirectly affect five pathways to continued offending due to psychological and behavioral effects. Researchers found that symptoms from depression and anxiety coupled with substance abuse did have a direct effect on imprisonment for women, regardless of the measure of childhood victimization.

The first pathway discussed in this study was based on childhood victimization, which has policy implications to address these issues for young women to help reduce imprisonment or offending in women. This model implies that the most effective treatment for women who struggle with child abuse along with mental illness and/or substance abuse are programs that help them develop strong coping skills from past trauma. When the effects of early victimization are left untreated, it is easy to assume that those women will most likely never recover from their mental illness or substance abuse and place them at a higher risk for engaging in criminal behavior or recidivism. If policies are set in place to have women go through therapeutic programs that focus on prior trauma, then it’s important to ensure that the woman is emotionally prepared for that process and not forced into it (Salisbury & Van Voorhis 2009). Most of the policy implications for this gender-specific pathway can also be based on the ideas discussed from strain theory (pp.5).

The relational model shows a similarity on the findings of social bond and strain theories discussed in Module 1. This model suggests that it is important to increase a woman’s ability to self-manage unhealthy relationships, because it would stabilize their emotions and reduce substance abuse. If the goal is to reduce overall offending or the likelihood of imprisonment, then programs that target addiction and mental illness should also consider a more holistic approach (addressing underlying life circumstances) such as childhood trauma. As mentioned before, based on strain theory, family-based programs can play a positive role in dealing with previous trauma.

Overall, the research I have done indicates the importance of changing our current criminal justice system to merge both evidence-based applications with gender-specific responses. If gender-specific theories are developed, we can analyze the gendered experiences that are critical in helping us understand how trauma effects criminality. There is overlap in the variables that explain the reason for committing crime for both genders, such as delinquent peers, criminal subculture or environment, lack of social skills, social strains, or the perceived cost and benefit of crime. However, there is still a need for reforming those approaches to reduce recidivism among young women. Most research does support the idea of women committing crimes based on emotional/mental issues, gender inequality, and relational/sexual abuse; meaning that policies should be reformed to address those underlying issues that are more likely to encourage crime in women when compared to men.

References:

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2020). Criminal Behavior: A Psychological Approach (12th ed.). Pearson Education (US).

Federal Bureau of Prisons. (2021, October 16). BOP Statistics: Inmate Gender. Retrieved February 2023, from https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_gender.jsp

NO ONE SIZE FITS ALL IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM. Danielle Rousseau. (2021, April 27). © 2023 Boston University. https://sites.bu.edu/daniellerousseau/2021/04/27/no-size-fits-all-in-the-criminal-justice-system/

Rousseau, D. (n.d.). Module 1. Learn.bu.edu.

Rousseau, D. (n.d.). Module 4. Learn.bu.edu.

Salisbury, E. J., van Voorhis, P., & International Association for Correctional and Forensic Psychology. (2009, June). Gendered Pathways: A Quantitative Investigation of Women Probationers’ Paths to Incarceration (No. 6). Criminal Justice and Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854809334076