CJ 725 Forensic Behavior Analysis Blog

Is being a Cop ok today?

Hi, my name is Officer Wynter and I decided to become a Cop in today's world. Law enforcement today is not looked at the same as it used to be. Back in the day, being a Cop was one of the most well-respected careers someone could get into. The job demands someone to risk their lives after all and be a hero. However, today if you want to risk your life and be a hero, its recommended that you become a firefighter or soldier. Due to some bad eggs in the field of law enforcement, the job on a global level has had to suffer. The disconnect that has developed between the community and the police has grown over the past few years. Due to this, the question arises, is being a Cop ok today?

In my opinion, I think when you become a cop today, you are taking not only a great job; but also, the baggage that has been left before. The job itself is very stressful with all the cons within it. Then you add the baggage, and you are now in an environment that some may classify as unhealthy. Due to these things is it recommended to take up the mantel. Today if you go to a group of officers, there is a high chance if you ask them advice on joining the field; they would talk you out of it or have you second guess yourself. This is not because of the danger but due to the fact that the job is hated now by the police and the community. I won't get into the known details on why we are where we are, but to summarize; the job as a whole is suffering due to bad officers making bad decisions. This has caused an image issue that is hard to be fixed due to the struggle of regaining trust between the community and the police. With the lack of trust this has made the job even harder. It is known how often officers commit suicide due to the stress of the job. An article on US Today stated "In 2020, 116 police officers died by suicide and 113 died in the line of duty, according to researchers. While the number of suicides dropped from 140 in 2017, study co-author Hanna Shaul Bar Nissim noted that 2020 numbers are likely an undercount due to stigma and shame, lack of reporting and people needing time to come forward." (Stanton, 2022)

https://abcnews.go.com/US/video/record-number-police-died-suicide-2019-68046762

(News, 2020)

These numbers are due to what the job entails and due to how much harder it has become. Lexipol, which is a policy management software for public safety, has come up with a list of many ways that we can see police officers getting stressed or burned out. Some of these examples include:"

- Isolation and withdrawal

- Being disengaged or unmotivated

- Physical exhaustion

- Nightmares and flashbacks

- Poor hygiene or apathy about one’s physical appearance

- Loss of empathy or compassion

- Relationship issues, including divorce

- Substance misuse and abuse

- Recurrent sadness or depression

- Resistance to feedback

- Resistance to change

- Reduction in meaningful work product

- Reduced job satisfaction

- Increase in citizen complaints” (Fish, 2018)

In the end, this post is not to scare people away from the job of being a cop however it is to shine a light on the reality of what it has become. I still believe though time and hard work, the disconnect can be fixed. The job gives you the ability to help, protect, and impact people's lives in many ways. This gives me the hope that it is still a good job to be in. To prevent the high suicide rates and the low moral from within, Self-care is essential in my opinion. Finding a suitable coping method or some way to decompress is essential in the field of law enforcement. The three things one should do is:

1. Cultivate a life outside law enforcement.

2. Develop good physical health habits.

3. Practice meditation and mindfulness.

By striving to incorporate these things into your life, a form of joy and good health will start to cultivate itself. Giving yourself the ability to be mindful and meditate can help you understand and handle stress. Taking care of your body physically can promote good health. Finally, having hobbies and a life outside of work will help you decompress. Through good self-care and building a better community relationship, the job of being a cop can be the well-respected job it used to be.

Resources

Stanton, C. (2022, June 10). Police, firefighters die by suicide more often than in line of duty. why rates remain high. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2022/06/10/high-suicide-rate-police-firefighters-mental-health/7470846001/

News, A. B. C. (2020, January 2). Record number of US police officers died by suicide in 2019, advocacy group says. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/record-number-us-police-officers-died-suicide-2019/story?id=68031484

Fish, D. (2018, February 14). How Self-Care Can Reduce Police Officer Stress. Lexipol. https://www.lexipol.com/resources/blog/how-self-care-can-reduce-police-officer-stress/

Should I Be Worried About Meeting a Psychopath?

The short answer is no. Less than 2% of the population can be diagnosed as a psychopath (Iken, 2023). Even less than that will do physical harm. Of course, emotional damage is just as significant. If you work in politics or business, you most likely know a psychopath already. Business, along with temp jobs, is where many psychopaths choose to work. For temp jobs, this difference is that they can stay in one place for a short time. It is a short-term job where they are not expected to be the best in their field. So they can cause as much harm as they want and will not have to stay there very long (Raine, 2013).

If you are concerned that you could end up being friends with or dating someone who is a psychopath, you can learn the signs. You can not ideally prevent yourself from avoiding psychopaths because the functioning ones could be working alongside you. An example from 2016 was when within a business group, one member named Bob would always say he could take on new projects. The rest of the group knew they would end up doing all the work because Bob did not do it. It might seem to higher-ups or supervisors that he is getting the job done because he is at all the meetings and might even be running them. However, he will pass on all the work to someone else (Myron Beard, 2022).

As frustrating and stressful as this is, it could happen to you even if there is not a psychopath around. Some people do not want to put the work in. And if you know the signs you are looking for, you can mostly avoid them. The percentage is low, and once you know the signs you are looking for, you should not worry too much about running into a psychopath.

References:

Iken, H. (2023, May 2). 20 ways to spot the psychopath in your life. Ayo and Iken. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://www.myfloridalaw.com/twenty-ways-to-spot-the-psychopath-in-your-life/

Myron Beard, P. D. (2022, September 7). High-functioning psychopaths in the workplace. Myron Beard Executive Consulting. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from http://www.beardexecutiveconsulting.com/beware-the-charming-psychopath/

Raine, A. (2013). The Anatomy of Violence: The Biological Roots of Crime. Random House LLC.

Webb, C. H. (2022). The problem of psychopathy. Psychology Today. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/drawing-the-curtains-back/202203/the-problem-psychopathy

A pandemic inside a pandemic

Gender violence against women is one of the clearest manifestations of the subordination, inequality and power relations of men over women; this violence is caused by the difference between the two genders; in other words, women suffer violence simply because they are women, regardless of their social status, economic or cultural level.

Some types of this type of violence are the following:

- Psychological: this type of violence has as its main contexts the home, partner or family, however, it does not have to reach harassment or humiliation, but can manifest itself as restriction, manipulation or isolation, which causes emotional and psychological damage, harming the development of a woman.

- Physical: is any type of action that causes suffering or physical harm, affecting integrity. For example, a blow, a push, etcetera.

- Sexual: refers to any action that violates or threatens a woman's right to decide about her sexuality and includes any type of sexual contact without consent.

- Economic: corresponds to actions (direct or through the law) that seek a loss of patrimonial/economic resources through limitation. An example of this is that women cannot own property or use their money or property rights.

- Work: women's access to positions of responsibility in the workplace is hindered, or their development or stability in a company is complicated by the fact that they are women.

- Institutional: authorities or officials complicate, delay or prevent access to public life, adherence to certain policies or even the possibility for women to exercise their rights.

Unfortunately, nationally it is estimated that "approximately 94 percent of crimes committed against women go unreported" (Mata, 2019). Of the total number of women who were assaulted, only 4% filed a complaint or filed a report with an authority and 2% only sought help from an institution. Among the reasons why women do not report their aggressors are the following:

- They considered that it was something unimportant that did not affect them.

- Shame

- Fear of threats or consequences

- She thought they would not believe her or that they would say it was her fault.

- Did not know how and where to report

- The aggressor was someone influential or with a certain amount of power

Gender violence in Mexico has been invisibilized for many years and only about 5 years ago began to have the visibility it deserves, all thanks to the participation of feminist collectives and various non-governmental groups which focus on supporting the population at risk.

However, with the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in all parts of the world, women were indirectly forced by the government to remain locked in quarantine with their aggressor, which raised the levels of gender violence that were already high. COVID-19 highlighted the lack of government action and inefficiency in terms of health and protection for women suffering violence in any sphere.

Data show that the confinement derived from covid-19 led to the records of violence against women in the home to increase 60% in Mexico, according to figures from the United Nations (UN).

From January to May 2020, data given from the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System, showed that during the confinement there was 375 alleged victims of femicide and 1,233 female victims of intentional homicide were registered, giving a total of 1,608; that is, 6% more than in the same period of 2019.

Likewise, during the same year, 23,460 alleged female victims of intentional injuries were counted and 108,778 emergency calls to the 911 number, related to incidents of violence against women had been attended.

The COVID-19 emergency is deepening gender gaps and inequalities that already existed and were ignored, as well as increasing the risk of violence for millions of women in Mexico. Latin America is considered the most violent region worldwide, this is largely due to the prevailing patriarchal culture that governs all customs and practices of daily life, leading to the naturalization of violence against women, the production of stereotypes, and the perpetuation and reproduction of discrimination (Moreno and Pardo, 2018).

Emotional abuse, such as insults, humiliation, and threats, are also a widespread phenomenon in Latin American countries. Many women reported that their last or current partner used three or more controlling behaviors, including isolating them from their families and/or friends, insisting on knowing their location at all times, and limiting their contact with family and/or friends (Bott, et al. 2012).

In Mexico, a large proportion of violent deaths of women are femicide murders where the victims are attacked because of the social condition of their gender. This terrible trend is on the rise: from seven violent murders of women per day two years ago, there are currently 10, according to the UN Women Office in Mexico (Villegas and Malkin, 2019). These data refer only to the most serious type of gender-based violence; however, other dimensions of this phenomenon are also highly present in the country, among which one of the most worrisome is domestic violence.

In response to the announcement of the Jornada Nacional de Sana Distancia, several civil organizations declared that measures should be adopted to guarantee women's access to a life free of violence during the current health crisis, and also demanded to ensure that policies aimed at combating gender violence are not neglected as a result of the readjustment of priorities. In particular, Amnesty International, the National Network of Shelters and X Justicia for Women highlighted the need to:

- ensure the provision of resources to shelters,

- guarantee the functioning of the justice centers,

- guarantee access to justice for this sector of the population.

In this context, domestic violence has proven to be one of the most worrisome issues. Almost two months after the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Mexico, the Shelter Network observed an increase of 5% in women's admissions and 60% in cases of counseling via telephone, social networks and email. In addition, the integrated National Refugee Red centers are already at 80% or 110% of their capacity, especially in entities such as Guanajuato, State of Mexico and Chiapas (Castellanos, 2020).

It must be recognized that Mexico faces a double contingency consisting of a crisis due to gender violence and the expansion of COVID-19, and that both require the same level of attention. As of April 21, 100 women have died from the coronavirus since it entered Mexico on February 28, while in the same period 367 women have been killed (Global Health 5050, 2020; Castellanos, 2020).

The normalization of violence against women, as well as other gender-based inequalities, is unfortunately a persistent phenomenon. If we want to make this problem visible in the context of a pandemic, it is essential to take optimal and strategic measures immediately.

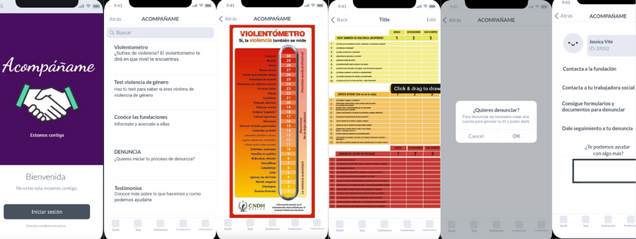

As a result, I began to develop an app to provide support to women who need help and receive it in an effective and efficient way without putting them at risk and at the same time eliminate the black number of complaints.

In collaboration with Casa Luna, a network of shelters in the Cuauhtémoc district of Mexico City, X Justicia and a network of colleagues from the university, I created the ACOMPÁÑAME application, which is a tool that facilitates women to receive psychological and physical help, as well as legal assistance and if necessary the opportunity to settle in a shelter, always taking into account their welfare in a comprehensive manner.

The app consists of first taking a test to find out if they are suffering violence and identify what type of violence it is in order to proceed in a better way. After that, women will have the option to contact specialized doctors to receive either physical or psychological treatment and as a final point they will be able to contact a network of lawyers to proceed legally against their aggressor.

This last point and the medical one are extremely sensitive points because of the information that is collected at the moment of contacting the victim, that is why all the data is treated with the utmost confidentiality giving the victim a folio number which also serves to prevent her aggressor from suspecting that something is going on. Both legal and medical actions being taken are given a film name so as not to raise suspicions and so that the victim is not at risk of further violence.

The pandemic created by COVID-19 came to an end, with the arrival of vaccines and movements of the different governments around the world; however, the pandemic of gender violence is far from coming to an end. It is necessary for each and every one of us to take action on this issue because, although it sounds cliché, the next woman who may suffer violence could be your mother, your sister or your daughter.

Initial layout of the app

References:

Mata, M. (2019). Cifra negra, 94% de delitos contra mujeres: JAPEM [Sitio web]. Retrieved may 2nd, 2023, from https://www.milenio.com/policia/cifra-negra-94-delitos-mujeres-japem

Inmujer. (2016). Definición de violencia de género [Sitio web]. Retrieved may 2nd, 2023, from http://www.inmujer.gob.es/servRecursos/formacion/Pymes/docs/Introduccion/02_Definicion_de_violencia_de_genero.pdf

Foreign affairs. (2020).La violencia contra las mujeres en Latinoamérica. Retrieved May 2nd, 2023. https://revistafal.com/la-violencia-contra-las-mujeres-en-latinoamerica/

New york times. (2019). ‘Not My Fault’: Women in Mexico Fight Back Against Violence. Retrieved May 2nd, 2023.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/26/world/americas/mexico-women-domestic-violence-femicide.html

Organización Panamericana de la Salud. (2020). Violencia contra las mujeres. Retrieved May 2nd, 2023.

International Center for Research on Women. (N/D). The Sex, Gender and COVID-19 Project. Retrieved May 2nd, 2023.

https://globalhealth5050.org/the-sex-gender-and-covid-19-project/

Can there be successful reform to our criminal justice system?

I am incredibly passionate about reforming our justice system and I think focusing on prevention, or an upstream model, to tackle crime is a great solution. To begin the process of prevention work, the roots of the problem needs to be uncovered. Knowing the histories and contexts of our justice system unlocks understanding on how foundational beliefs shape the experience and outcome of individuals involved. When evaluating the process and results of the US system it is clear that the concept of justice is defined in a unique way. Who decides how a community measures justice? Digging for the truth reveals what this system is effective in achieving. Unfortunately, in the US, the origins explain an intentional pattern of harm: a system born out of oppression, control, and racism. This punitive system was merely a method to destroy communities of color and establish a nation based on individualism and capitalism. Now we see how those national values stand in opposition of true justice.

The article “The Foundational Lawlessness of the Law Itself: Racial Criminalization & the Punitive Roots of Punishment in America”, tackles the topic of US Justice System reform. The topics discussed helped me recognize how the origins of our system make it almost impossible for reform. The author, Kahil Muhammad looks back at American history to discover how this society came to define the criminal and how a criminal was dealt with. This examination revealed that the US strategically criminalized certain identities: “As generation after generation of White colonists and later citizens moved West, the choice to define Native populations and Mexicans as savages or criminals by law, custom, and practice rationalized the eventual creation of the nation” (p. 109). The criminal system was created to punish communities of color for merely existing and to gain control. White settlers perpetuated the idea that “An individual's deviance was a result of ‘cultural pathologies’ and bad parenting ensured delinquency and crime, to which policing and incarceration were the most appropriate responses” (Muhammad, p. 117). When looking back, “Criminal anthropologists assessed female deviance, in part, by subjects’ proximity, or distance from, Western ideals of femininity, morality, and virtue” (Muhammad, p. 112). These racist perspectives still remain to this day, as the justice system has failed to evolve, rather we see that “crime and punishment, in other words, emerged as the platform for the racial inequities established during the colonial era to flourish” (Muhammad, p. 109-110). Even outside of the adult justice system, we often see for Black youths that “The denial of the special protections of the juvenile court … reflected a pervasive view that Black youth were ‘presumed criminal’” (Muhammad, p. 113-114). The criminal justice system was created to enforce and uphold racist ideals. The system conceptualized the criminal as any person of color, and this stereotype persists. There is no justice for all in a system made to maintain white supremacy.

Included in the article is a quote from the Union Major General Carl Schurz, “But although the freedman is no longer considered the property of the individual master, he is considered the slave of society, and all the independent state legislation will share the tendency to make him such.” He pointed out that although slavery was now illegal, the US found a way to legalize a new form of slavery. Years later this still remains the truth. Black men make up the majority of incarcerated individuals. The system that existed back then still exists now and because the intentions were to criminalize Black men this problem is very much alive and well. I found it interesting that “incarcerated White men saw themselves as Black-adjacent. ‘Some even identify themselves as marked by that history of racial discrimination in recognizing that anti-black lawmaking is behind the sweeping legislative changes that widened the net of the criminal justice system, eventually catching them”(Muhammad, p.111). It makes you question what it truly means to be “Black-adjacent”. It seems that in this context being Black is to be ‘unwanted’ in society or ‘deviant’. By existing in a Black body the US feeds you this message. And when White individuals feel this way, to them it is synonymous with Blackness.

In the book Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times, the author is “convinced that much crime and violence is a way of asserting personal identity and power” and that the violence perpetrated by offenders “feeds on low self-confidence and fractured self-esteem”(Zehr, ch. 3). Similarly, the article “An Abolitionist View of Restorative Justice”, describes crime as a “communicative act, expressive conduct, ‘a clumsy attempt to say something’”(Ruggiero). If you are a part of a society that places negative labels on members of your race, they raise you to hate who you are.

If we follow the logic established by these authors, there is no question as to why crimes will be committed. There is also no question as to why people will reoffend. If the current solution further instills self hatred, the problem is perpetuated. Instead of searching for the root cause of the violence or crime in our society, the criminal justice system locks away the symptoms to the “failings of economic, political, or social systems, which consequently deters the reform of these systems'' (Ruggiero).

This same article discusses Durkheim's theories on social order and presents three “Unity Patterns''. In my opinion, the most utopian patter is the Organic Unity Pattern which “is enacted when individuals develop feelings of reciprocity due to the role and social rewards they enjoy in relation to similarly satisfied individuals”(Ruggiero). If we strive for a society of community and social order, this is one healthy way to achieve it. Currently, we do not have this. Although it is a goal that may never be attained, it's one I think we should strive for. There is no reciprocity and this seems like the true root cause of criminal behavior. The US Justice System fails to function because it perpetuates, instead of addressing the problem.

Works Cited

Howard Zehr. (1995). Changing Lenses : Restorative Justice for Our Times. Herald Press.

Muhammad, K. G. (2022). The Foundational Lawlessness of the Law Itself: Racial

Criminalization & the Punitive Roots of Punishment in America. Daedalus, 151(1), 107–120. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48638133

Vincenzo Ruggiero, An abolitionist view of restorative justice, International Journal of Law,

Crime and Justice, Volume 39, Issue 2, 2011, Pages 100-110, ISSN 1756-0616, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2011.03.001. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/S1756061611000279)

Trauma and Suicide within Law Enforcement

Trauma is a serious thing that needs to be taken a closer look at, it is the third largest cause of death worldwide for males and fourth largest death worldwide for females, it was estimated to have caused 10% of all deaths in 1990 (Bourbeau, 1993; Girolami et al., 1999; Murray and Lopez, 1996). “Trauma is defined as one or more events perceived to the individual as harmful or life-threatening, usually causing adverse effects to the individual’s well-being” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019).

Law enforcement officers are at great risk of being exposed to trauma during their work, and the officers are also at a greater risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), increased suicidal risk, and increased substance use (Collazo, 2022). Police officers are at great risk of being exposed to multiple traumas throughout their careers, it has been estimated that they witness anywhere from 10 to 900 traumatic events throughout their career (Papazogulou & Tuttle, 2018; Rudofossi & Lund, 2009). It is estimated that 15% of male and 18% of female law enforcement officers develop PTSD compared to 1.3% to 5.5% of the general population (Berger et al., 2012, Frans et al., 2005, Hartley et al., 2013).

1.216 first responders ended their own life from January 1st, 2017 to February 27th, 2023, 811 of these individuals were law enforcement officers who majority were active officers at the time (Blue help, 2023). As of February 27th, 2023 16 law enforcement officers have committed suicide, 12 of those were active officers (Blue help, n.d). The trauma that these officers have been exposed to throughout their careers is the leading cause of their suicide and it is important that all officers have access to receive the help that they need without being judged for it. In 2020 there was a discussion on the topic in Dr.Phil who talked to the families of some of these officers and explained that there is a lack of help for them within the police department and that most officers do not seek help out of fear of being judged. In 2019 180 male and 16 female officers lost their lives because they were unable to seek help to the trauma that they were exposed to in their workplace, total of 197 law enforcement officers lost their lives that year which is unacceptable. It is important that not only law enforcement officers but all first responders have access to mental health services that can help them to deal with the trauma that they are exposed to while they are on duty because they are the ones who are responding to situations that most would run away as quickly as they possibly could.

In 2018 the Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act 2017 was signed into law, this act recognizes that law enforcement officers need support with their mental health. This act ignores the old way of thinking about mental health where only “crazy” people need help and it is taboo to seek help from a mental health professional. The act is a huge step in the right direction however, there are still approximately 150 law enforcement officers ending their own lives every year and it is clear that the stigmatization of mental health is still a problem and it needs to be changed. It is extremely important to understand that it is okay to talk about your problems and not to judge others who do because it should be encouraged especially for first responders who are often the first people on a scene that is traumatizing.

References

Becker, C. B., Meyer, G., Price, J. S., Graham, M. M., Arsena, A., & Armstrong, D. A. (n.d.). Law enforcement preferences for PTSD treatment and crisis management alternatives. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(3), 245-253. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.001

Bourbeau, R. (1993). Analyse comparative de la mortalite violente dansles pays developpes et dans quelques pays en developpe-ment durant la periode 1985-1989. World Health Stat Quart, 46, 4-32.

Collazo, J. (2022). Adapting Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to Treat Complex Trauma in Police Officers. Clini Soc Work, 50, 160-169. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1007/s10615-020-00770-z

Congress. (2017). S.867 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act of 2017. Congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/867

Frans, Ö., Rimmö, P., Åberg, L., & Fredrikson, M. (n.d.). Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111(4), 290-291. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00463.x.

Girolami, A., Foex, B. A., & Little, R. A. (1999). Changes in the causes in the last 20 years. Trauma, 3-11. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1177/146040869900100101

Hartley, T. A., Violanti, J. M., Sarkisian, K., Andrew, M. E., & Burchfiel, C. M. (2013). PTSD symptoms among police officers: Associations with frequency, recency, and types of traumatic events. International journal of emergency mental health, 15(4), 241-253. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4734407/

McGraw, P. C. (2020, September 11). Behind The Badge: Is 'Code Of Silence' Leading More Law Enforcement To Take Their Own Lives? Dr. Phil. https://www.drphil.com/videos/behind-the-badge-is-code-of-silence-leading-more-law-enforcement-to-take-their-own-lives-alt/

Murray, C. J.L., & Lopez, A. D. (1996). The global burden of disease. The Harvard School of Public Health.

The Numbers. (n.d). Blue H.E.L.P. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://bluehelp.org/the-numbers/

Papazoglou, K., & Tuttle, B. M. (2018). Fighting police trauma: Practical approaches to addressing psychological needs of officers. SAGE Open. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1177/2158244018794794.

Rudofossi, D., & Lund, D. A. (2017). A Cop Doc's Guide to Public Safety Complex Trauma Syndrome: Using Five Police Personality Styles. Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315225142

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administartion. (2022, September 27). Trauma and Violence - What is Trauma and the Effects? SAMHSA. https://www.samhsa.gov/trauma-violence

Mental Health and Mass Murders: The Connection between Trauma and School Shootings

Mental Health and Mass Murders: The Connection between Trauma and School Shootings

Almost every type of violent criminal has a motive or driving purpose that makes them want to commit an act of violence against another human being. A special type of violent criminal is the school shooter, who is an individual who takes it upon themself to target innocent children and adults in a classroom setting. One of the most influential factors of a school shooter’s development into a killer is the trauma that they experienced at an early age. Kristen Rowe from the American University Washington College of Law explains that “68% of school shooters witnessed or experienced some form of childhood trauma” (Rowe, 2022). Being exposed to emotional or physical trauma at an early age pushes these children, mostly young boys, to alienate themselves from their family. This makes it much more difficult for them to socialize with children at their school.

Even though the trauma that has been done on these children is most likely something they will have to live the rest of their lives with, intervention is a possibility and one of the best approaches to preventing a school shooting. Deborah M. Weisbrot, M.D. examined the family-life of multiple school shooters and made some interesting conclusions about the importance of spotting school-shooter behavior early. In fact, there were several recommendations that Weisbrot provided, which included: having a child/adolescent psychiatrist evaluate the threats of a school shooting, ensuring that the school consultant is prepared to interpret complex individual, family and group dynamics potentially leading to the expression of threats, such as retaliation for bullying and teasing, and that effective treatment options are made available to the troubled child and their family (Weisbrot, 2008).

Lastly, I’d like to talk about the efforts that should be made towards dedicating resources to victims of school shootings that survived the encounter. These individuals are victims because they have to carry the burden of witnessing others being killed and the stress of almost being killed themselves. This is a severe form of mental trauma that would weigh anyone down. Maya Rossin-Slater from Stanford University’s Institute for Economic Policy Research researched the rate of antidepressant medication prescriptions being written for residents that lived within five miles of a school shooting and discovered some interesting findings. Rossin-Slater’s results indicated “that the average monthly number of antidepressant prescriptions written to youth under age 20 by providers located near schools that experienced a fatal shooting was 21.3 percent higher relative to providers located farther away in the two to three years following a shooting than in the two years before” (Rossin-Slater, 2022).

References:

Rowe, K. (2022, July 24). Influence of childhood trauma on perpetrators of mass shootings. crimlawpractitioner. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.crimlawpractitioner.org/post/influence-of-childhood-trauma-on-perpetrators-of-mass-shootings

Rossin-Slater, M. (2022, June). Surviving a school shooting: Impacts on the mental health, education, and earnings of American Youth. Retrieved February 25, 2023, from https://siepr.stanford.edu/publications/health/surviving-school-shooting-impacts-mental-health-education-and-earnings-american

Weisbrot , D. M. (2008, August). Prelude to a School Shooting? Assessing Threatening Behaviors in Childhood and Adolescence. Retrieved February 25, 2023, from https://web.archive.org/web/20170829222303id_/http://www15.uta.fi/arkisto/aktk/projects/sta/Weisbrot_2008_Prelude-to-a-School-Shooting.pdf

Forensic Behavior Analysis: Self Care in the CJ Field

The criminal justice field is a difficult field to be involved with, whether you are an officer, a counselor, analyst, dispatcher, etc the list goes on and on. Within the criminal justice field, we see quite a high rate of burn out with jobs that are needed to have a functioning society. In today's society it is clear that it is imperative that the current working individuals in the criminal justice field have to make changes to our systems. I do believe that the criminal justice system has been broken and built on negative things that don’t represent our country. We want to build a fair, equal criminal justice system for everyone that resides in this country. That is quite a tremendous pressure on all of us and it can create burn out amongst this field. Not to mention in some law enforcement jobs we see high amounts of suicide rates, such as when you look at correctional officer jobs. In 2018, UC Berkeley did a study that showed correctional officers are at one of the highest risks for depression, PTSD, and suicide, as well as that suicides among law enforcement workers have been increasing over the years recently, (Barr and Thomas).

To combat the burnt out and poor work satisfaction we see in criminal justice workers, I think that we need to work on promoting self-care for individuals. Encouraging criminal justice workers to take time for themselves and to take a step away from the job is how we can ensure that we have the best version of ourselves working for others. It could highly reduce burn out rates and allow people to really enjoy their jobs by taking a step away and coming back to the job they love doing. Taking a long weekend, using time off to go do something you love or spending quality time with the people you love could improve job satisfaction as well. Fully stepping away from your job and doing things that make you happy is the best form of self-care. We cannot allow ourselves to lose ourselves to work as it's a disservice to the criminal justice system, as well as ourselves. The most important thing people need to realize is that putting yourself first and ensuring that you are feeling your best self is how to enjoy your job and not feel as though you're going to work against your will.

References:

Barr, L., & Thomas, P. (2019, October 17). [Review of Correctional officer suicides in 2019 tied for most in single year: Union president]. Retrieved February 28, 2023, from ABC News website: https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/correctional-officer-suicides-2019-tied-single-year-union/story?id=65828169

Learning Theories

As I have mentioned before, Learning theories have always been my favorite ones to understand crime. Not only can they explain crime, but they also leave the door open to change. I wanted to extend our discussion about theories and put together some research that I have previously done on learning theories. "A scientific theory of crime should provide a general explanation that encompasses and systematically connects many different social, economic, and psychological variables to criminal behavior" (Bartol & Bartol, 2021. p, 4).

Sutherland's Differential Association Theory (DAT) states that behavior is learned through interactions while communicating with our closest groups. Sutherland's DAT has nine principles (Cullen et al. 2018):

- Criminal behavior is learned.

- Criminal behavior is learned through our communication processes.

- Criminal behavior is learned from our intimate groups.

- Learning criminal behavior involves techniques and the motives to commit a crime.

- The legal code is seen as favorable or unfavorable, which is how motives to commit criminal behavior are learned.

- A person becomes a criminal when the consequences of violating the law are more favorable than unfavorable.

- Differential association varies in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity.

- Learning criminal behavior entails the same ways in which we learn any other type of behavior.

- Criminal behavior is not excused by general needs and values.

Aker's Social Learning theory (SLT) states that behavior is learned and reinforced by those groups closest to us through instrumental conditioning. There are four significant concepts (Cullen et. al 2018. p, 81):

- Differential association: the primary groups we associate with expose us to definitions and models to imitate.

- Definitions: are the meanings we give to behavior.

- Imitation: This is engaging in behavior after seeing others.

- Differential reinforcement is the balance of rewards and punishments, depending if we see them as positive or negative.

A study by John K. Cochran, Jon Maskaly, Shayne Jones, and Christine S. Sellers (2017), Using Structural Equations to Model Aker’s Social Learning Theory With Data on Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). The study included people that were in a relationship or had a relationship before. The results in both models proved that SLT could explain IPV in prior and current partners, especially the variables for differential reinforcement, definitions, and imitations. Akers's Social Learning theory has proven to be true when tested and has also shown that it is a general theory that can explain different types of crimes.

The code of the street by Elijah Anderson. “The code of the street is a set of informal rules governing interpersonal public behavior, particularly violence. The rules prescribe proper comportment and the proper way to respond if challenged” (Anderson, 2000. Pag. 33). The code has existed for years in different forms through different civilizations, but it has always been there. The perpetuation of the code continues in those societies that are often at a disadvantage. We can see street and descent families and how the children are influenced and learn from those around them.

Learning theories explain how people can learn criminal behavior from those around them. But they can also explain why people change or do not commit criminal acts when they are not accepted or committed by those closest to us. Specific theories can explain some crimes better than others. For example, developmental and trait theories can explain life-course-persistent offenders and adolescent-limited offenders. But, intersectionality between theories exists, and it helps to understand crime better and to put more pieces together, as there is not only one reason why crime happens. Regarding learning theories, nature vs. nurture and strains are essential to remember.

References:

Anderson, E. (2000). The code of the street. Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. Norton & Company Inc.

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2021). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach (12th ed.). Pearson.

Cochran, J. K., Maskaly, J., Jones, S., & Sellers, C. S. (2017). Using Structural Equations to Model Akers’ Social Learning Theory With Data on Intimate Partner Violence. Crime & Delinquency, 63(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128715597694

Cullen, F. T., Agnew, R., & Wilcox, P. (2017). Criminological Theory: Past to Present. 6th edition. Oxford University Press.

Geographic Profiling for No-Body Homicides

Investigative psychology, or more commonly known as profiling, has become very popular in recent years due to popular TV series like Criminal Minds (Bartol and Bartol, 2021). The basis behind investigative psychology, coined by David Canter, involves the application of psychological research and principles to the investigation of criminal behavior (Bartol and Bartol, 2021). Our textbook breaks down profiling into five categories, one of which is geographical profiling (Bartol and Bartol, 2021). Bartol and Bartol (2021) describe geographical profiling as a technique used to help locate geographical locations related to a serial offender’s residence or base of operations as well as where the next crime by this perpetrator may take place. This process tends to be highly actuarial and generally involves sophisticated computer software programs, like Criminal Geographic Targeting Program (CGT), Crimestat, or Dragnet, that apply statistical probabilities to areas that seem to fall within the perpetrator’s territory based on their known movement patterns, comfort zones, victim-searching patterns, and the location of the previous crimes (Bartol and Bartol, 2021). Although geographic profiling does not lend to the demographic, motivational, and psychological features of the crime or the perpetrator, it focuses more on how the location of the crime relates to the residence and/or base of operations for unknown offenders of both violent crimes and property crimes (Bartol and Bartol, 2021).

Another form of geographical profiling that was not mentioned in our textbook was brought to my attention about a year ago and it involves the inverse process of what is described above – instead of finding the offender, it focuses on finding undiscovered clandestine graves, body dumps, or scattered remains when the offender is known or still at large but their behavior has revealed a pattern (Moses, 2019). For no-body homicides, or cases in which the victim is suspected to be deceased, but their remains have not been located, with known offenders, investigators can gather all the areas the perpetrator is familiar with, their personality preferences, and risk factors, like risk of being discovered when disposing a body, to try to narrow down where the body may be located (Just Science, 2022). This type of profiling is very important to the field because it helps to allocate resources appropriately, converge manpower on areas that have the highest chance of reaping success, and increases the odds of proper prosecution (Just Science, 2022).

This type of profiling is primarily actuarial and based on statistics, or base rates, gathered by the FBI regarding body disposal (Bartol and Bartol, 2021; Just Science, 2022). For example, people who kill their own children or close family members (not including spouses) often dump the bodies in a one to five mile radius from the home where they were likely killed (Just Science, 2022). This is evident in the death of Caylee Anthony, where her remains were found in a wooded area close to the family home prosecution (Just Science, 2022). In cases where the victim is an intimate partner or spouse, the offender will likely move the body further away, usually 30 miles or more from where they were killed (Just Science, 2022). This is evident in the death of Laci Peterson and her unborn child, where they were dumped in the San Francisco Bay about 90 miles from their home (Just Science, 2022). If the victim was a friend or acquaintance, they are usually found within a radius of ten miles from where they were killed (Just Science, 2022). Additionally, if the victim was a stranger, they may be found closer to the offender’s known area than an acquaintance, but the offender may not try to hide the body, whereas for acquaintances and friends they might (Just Science, 2022).

With humans, sometimes their motivations may vary. For example, some people may try to hide the body so it won’t be found, while others, like serial killers, may want the body in a place where it will be found fairly quickly or in a place where they can return to it easily (Just Science, 2021). Additionally, distance is understood differently among different groups of people (Just Science, 2022). For example, people who live in rural areas travel long distances without a lot of traffic to conduct business, so their perception of distance may be quite different than someone who lives in a metropolitan area (Just Science, 2022). Lastly, in spur of the moment type homicides, the offenders may leave the body where they are or make a haphazard attempt to move it (Just Science, 2022). These differences in perceptions, personality, and motivations are calculated into geographic profiling, so inconvenient areas can be excluded (Just Science, 2022).

If you’re interested in learning more, I interviewed Dr. Sharon Moses in a Just Science podcast episode about this topic here: https://forensiccoe.org/podcast-2022casestudies-part1-ep3/.

References:

Bartol, A. and Bartol, C. (2021). Criminal Behavior: A Psychological Approach. (12th Edition). Pearson.

Moses, S. K. (2019). Forensic Archaeology and the Question of Using Geographic Profiling Methods Such as “Winthropping”. In Forensic Archaeology: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 235-244). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03291-3_15.

Just Science. (2022). Just Forensic Archaeology and Body Dump Sites. Forensic Technology Center of Excellence. https://forensiccoe.org/podcast-2022casestudies-part1-ep3/.

Police Officer Suicide and Suicide Prevention

Tony Ford

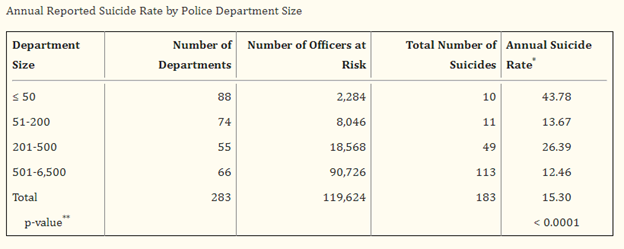

It is a sad fact that police officers are more likely to die from suicide than in the line of duty. In 2020, 116 police officers died by suicide while 113 died in the line of duty (Stanton, 2022). In 2021, that number rose to 150 officers dying by suicide (Leone, 2022). Tragically, law enforcement officers have a 54% increase in suicide risk when compared to the civilian population (McAward, 2022). The problem seems to be even worse in smaller departments, which may not have an extensive support system or peer support resources. A 2012 study published in the International Journal of Emergency Mental Health found that departments with less than 50 full-time officers had a suicide rate over triple that of departments that had over 500 full-time officers (Volanti, et.al, 2012). This is concerning, as 49% of the police departments in the United States employ less than 10 full-time officers (Volanti, et.al, 2012).

Figure 1 Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine. Figures are per 1,000 officers.

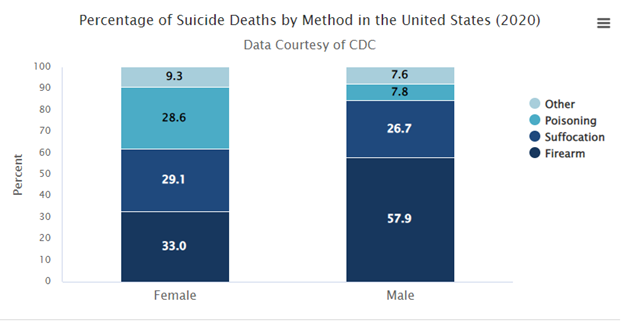

In the United States, most suicide attempts among the general population are not fatal (McAward, 2022). Yet, when a firearm is used, the chances of a suicide attempt becoming fatal skyrocket. Suicides that involve a firearm have a fatality rate greater than 82% (McAward, 2022). Police officers nearly always have a firearm available. In fact, the majority of law enforcement suicides happen at home, using the officer's own service weapon (McAward, 2022).

Figure 2 Data courtesy of the CDC

Though more study is needed, the lower suicide rate in larger departments may indicate that many of the mental health and peer support programs in use are having a beneficial effect. My department, which is over 500 sworn officers, has a robust peer support system that has officer volunteers. These volunteers go out to officer-involved shootings to offer support for officers that may need them. In addition, in 2021 we hired an on-staff clinician. She also comes out to deadly-force incidents and is available to speak with the officers. No officer is forced to take advantage of either resource, but they are there if needed. The peer support system has become more robust over time, with more and more offices volunteering to serve in the program. The clinician is also available for counseling services, and officers may go for a session either on or off duty. They do not have to involve their chain of command in the scheduling, and the clinician provides nothing other than a work excuse note. The clinician will also likely become more effective as she spends time with officers and learns the stressors of the job. The support is welcome, as we have lost three officers to suicide since I started in 2002.

There are other things departments can do for suicide prevention. John Becker, a former police officer turned clinician in Pennsylvania, recommends programs for positive stress relief, such as softball, basketball, or bowling leagues (Becker, 2016). He also says that supervisors have a role to play in ensuring open communication (Becker, 2016). Support, he says, doesn’t have to be a group hug. Simply asking a subordinate how their shift went that day would encourage communication (Becker, 2016). He also points out the numerous benefits of better mental well-being in a police force, benefits that extend beyond suicide prevention (Becker, 2016). A healthy department will have fewer complaints and lawsuits, fewer officers calling in sick, fewer grievances and resignations, and even fewer on-the-job injuries (Becker, 2016).

There is no field quite like policing. The higher occurrence of suicides in the field should be met with programs and professionals who understand what officers are going through. Many times the best professionals for that task are other police officers. Departments should strive to have a holistic approach to officers' mental well-being, and show officers that they care about their mental health. A department that ignores this important aspect of employee care is doing a disservice to their officers and the public that they serve.