CJ 725 Forensic Behavior Analysis Blog

Internet and Sexual Offenders

Back in model five it was discussed that technology has increased the numbers of sexually based crimes. Producers of child pornography is statically more likely to be someone the child knows, who has complete and legitimate access to the child. Technology has also led to more sexual grooming. Research into online sexual grooming has largely been focused on the stages of grooming, typologies of offenders, or comparisons with people who download abusive sexual images of children. Extraordinarily little attention has been paid to internet affordance and the role these might play in the offending behavior, the development of expertise, and the avoidance of detection. There was a qualitative study done on 14 convicted men, those convicted of online grooming. Analysis indicated that the internet served to create a private space to engage in purposive, sexual behavior with young people. The internet aided in the fantasy, and for some was precursor to an offline sexual assault. Grooming is the process by which an individual prepares a child and their environment of sexual abuse to take place, including gaining access to the child, creating compliance and trust, and ensuring secrecy to avoid detection. (Craven, Brown, and Gilchrist, 2006). Sexual grooming pre-dates the internet, Lanning (2001) described grooming activities in relation to the internet, individuals attempted to sexually exploit children by seducing their targets with attention, affection, kindness, and gifts. Between 2000 and 2006 showed a 21 percent increase in online predators.

Are online sexual offenders different than other sexual offenders? There are studies how argued that online sexual offending is simply what happens when conventional sexual offenders have access child pornography through mail-order services or through personal trades now access large volumes of child pornography online. Similarly, those who might have approached children in public such as malls, are now contacting children through social network sites, messaging, and other technologies. However, there is a counter study that states that the internet has created a different type of sexual offender. Specifically, the anonymity of the internet, accessibility of child pornography; and greater opportunities to trade child porn, contact potential victims, and engage in conspiracies to commit sexual offenses have facilitated illegal sexual behavior.

Quayle, Ethel, Allegro, Silvia, Hutton, Linda, Sheath, Michael, & Lööf, Lars. (2014). Rapid skill acquisition and online sexual grooming of children. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.005

Seto, Michael C, & Karl Hanson, R. (2011). Introduction to Special Issue on Internet-Facilitated Sexual Offending. Sexual Abuse, 23(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063211399295

What 9/11 Taught Us About Trauma

September 11, 2021 will mark 20 years since the terrorist attacks in New York City. Since then, we have learned how to communicate when phone and cable lines are down, and also what to do when evacuation routes are blocked as well as when roads to the nearest medical facilities are blocked. Not only did we learn important life saving lessons, but we also learned a lot about trauma and PTSD.

The powerful emotions that erupted from that day were not only felt in New York City or in surrounding states, but also across the United States and around the world. Two women who were in different parts of the city that day both experienced PTSD. Marcy Borders, who became known as Dust Lady, struggled for the decades following the attacks from depression as well as addictions to alcohol and crack cocaine. She is unfortunately one of many survivors who have struggled with mental illness and substance abuse since then. Esperanza Munoz witnessed the towers falling from a distance, but that doesn't change her experience. To this day, she still has flashbacks and nightmares as well as anxiety whenever she hears sirens or a plane flying overhead. She can't even step into New York City without panicking.

Many studies have been done on the affects of 9/11 and the first 9/11 trauma study was conducted on October 29, 2001. The team interviewed a huge range of survivors from the first responders, the recovery workers, those who survived the attacks themselves, and to those who lived in surrounding areas. They found that 96% of the survivors reported having experienced at least one symptom of PTSD 2 to 3 weeks after the tragedy. Of that 96%, a majority were still experiencing multiple symptoms 2 to 3 years afterwards. Another study on 9/11 focused on about 11,000 first responders and it was completed over a total of 8 years. They found that during the first year, at least 70% had actually never met the diagnoses criteria for PTSD but years later had many symptoms. Their study told them that the timelines of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder symptoms varied and hit people differently. They also found that these timelines are affected by the duration of the traumatic experience, the trauma-related medical experience, and also any prior psychiatric problems.

Not only have we learned in the almost two decades since then that PTSD symptoms rise up at different times for everyone and that trauma can be experienced by everyone, but psychologists themselves have learned new ways to react to major traumatic events like this one. Shortly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, psychologists themselves would ask those who were on Ground Zero or in the surrounding areas how they felt and if they were experiencing any symptoms. Years later, they have learned that not everyone is going to be traumatized and that everyone processes trauma differently. A new method that psychologists have come up with is called Psychological First Aid. Instead of asking the individual how they feel in the aftermath, the psychologist will offer the survivor services and give them information for the services. This not only allows flexibility, but it is also still reducing the distress caused by the event or events.

Unfortunately, that September day changed everything. Airport security is even tighter, rates of mental illness and PTSD have risen, and rates of substance abuse have risen. But at the same time, there have been positive changes that are allowing the country to prepare themselves for the next traumatic event or even to change the mental health field.

Resources

Cook, J. (2016, September 09). September 11th attacks: What we learned about trauma. Retrieved April 27, 2021, from https://time.com/4474573/911-september-11-trauma/

Pearson, C. (2011, November 09). 10 years after 9/11: What we now know about trauma. Retrieved April 27, 2021, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/911-and-mental-health-a-n_n_951060

Researcher finds 9/11 attacks led to new understanding of mass trauma. (2011, August 31). Retrieved April 27, 2021, from https://news.columbia.edu/news/researcher-finds-911-attacks-led-new-understanding-mass-trauma

Surviving 9/11: Trauma and substance abuse. (n.d.). Retrieved April 27, 2021, from https://www.drugrehab.com/featured/9-11-trauma/

NO SIZE FITS ALL IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

“Not all populations within the criminal justice system are the same, and in order to foster effective policy and programming, it is important to recognize this fact.” (Rousseau, 2021). This simply states that not every criminal is the same and not all resources are applicable to every inmate; more specifically inmates that are women. “Theory and treatment strategy… cannot and should not be applied … across—the–board.” (Rousseau, 2021). This is said because dealing with women inmates creates a different demand of an approach compared to men i.e., prison nurseries for pregnant inmates. Another example is that women are more likely to have a mental illness subject to anxiety, depression and PTSD compared to men inmates. This may be due to the different upbringing or life experiences such as women may encounter more of a chance of physical, emotional and sexual abuse. “A majority of women in the system, up to 70%, repeat a history of abuse as a child or adult … and a higher percentage of women have a history of substance abuse compared to men.” (Rousseau, 2021). Including, “The prevalence of sexual abuse reported among female offenders varies, although generally appears higher than figures reported in male offenders finding 85% of a sample of female offenders reported suffering childhood sexual abuse, and there have been other findings of 80% of a sample female offender suffering child-adult victimization.

Photo by: Frieda Afary

Photo by: Frieda Afary

The unique issues in working with female offenders is the highlighted overlap of “mental illness, trauma, addiction, and relationship issues.” (Rousseau, 2021). Additionally, it is notated that the “relative importance of sexual abuse in the criminal pathways of females, finding women who had been a victim of sexual abuse were significantly more likely to be arrested for a violent juvenile offense and an offense as an adult.” (McKeown, 2010). Simply, that it appears that women issues may stem from repeated sexual abuse from their past and/or currently. Moreover, there are findings that women are often subject to repeat victimization. Revictimization are consistent with the findings that half of women incarcerated are those who have been sexual abused in the past as opposed to 3% of men. It appears that revictimization is relatively more common in female offenders. Because “the grater the severity of abuse in terms of frequency and duration, the greater the level of trauma.” (McKeown, 2010).

What needs to be highly considered when determining strategies for women is that it is reported that women are more likely to have higher levels of psychological or mental illness. For example, research shows that women prisoners have a higher level of schizophrenia, 19%, compared to males, 7%, and 67% of woman have lifetime depression compared to 30% of men. (McKeown, 2010). Further, the difference may be due to the overlap of substance abuse that is also more common in female prisoners than males. Overall, it is important to draw the link between psychological help and violent behavior.

Such factors are examples of the developmental, social learning and biological. Biological theory focuses merely on the aspects of biology, this can be interpretated that you are born the way you are born. Social learning theory, that is, focuses on the aspects of human interaction and what is learned through such interaction. Meanwhile developmental theory focuses on the continuation of one’s nature and environment. Many factors are to be looked at when determining an incarcerated women’s treatment. One fit cannot fit all especially when comparing men and women because more women than men have been abused, involved in substance abuse and have mental issues. Biology comes into play within this discussion because many of these women may have been born with any psychology discrepancies. Moreover, this issue may overlap into the social learning theory because many women may feel isolated or have a hard time communicating with others. If the issue of miscommunication, isolation, or antisocial behavior is at issue then such factors will also overlap within their developmental environment because many women will then choose their nature/environment based on such factors. For example, a woman who is antisocial may get attached to a male who is abusive or one who may be the individual to introduce them to addictive drugs. When analyzing treatment for an incarcerated individual, you must take them as a whole to effectively solve their problems rather than pin point to a sole factor that may be contributing to their wrongful behavior.

Photo by: Jodee Redmond

With that being said the important components when establishing treatments should be of those that are gender responsive and help treat those with trauma and/or addictions. The purpose is to analyze from early life to sexual abuse and street life to measure the significant impact that the abuse had cause mentally, physically and emotionally. Ultimately this measurement has found abuse has led to, unhealthy sexual practices, early traumas and substance abuse. “Prevalence rates for physical and sexual victimization among female inmates were also found to be more significantly higher for inmates with a mental disorder than those without a mental disorder.” (Wolf, 2012). What I thought was interesting this week about this topic is that their trauma informed programming. Here, there’s a therapist for women prisoners. This tactic provides training for all staff within the correctional facticity. As I learned before that being able to incorporate the criminal justice system with medical professionals will help understand on how to treat individuals with mental illnesses. For example, “security staff… came to realize that a women’s reaction might not be out of aggression, but instead a trauma response.” (Rousseau, 2021). Further it’s important to incorporate mental health-based treatments like therapy to help reduce revictimization or reoffending.

I think women need to receive different treatment than men to it to be effective and more specifically each case is different amongst women themselves. There was a study conducted to examine the implementation and effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder amongst incarcerated women. The study has examined that majority of women have experienced childhood trauma and had serious mental illnesses. Guidelines has been put into place by the “National Institute of Corrections called for integrated interventions that target the co-occurrence of trauma, PTSD, and SUD among incarcerated women.” (Wolf, 2012). This manualized intervention is designed to address the individuals cognitive, behavioral, interpersonal and case management needs. This includes their deficiencies in antisocial behaviors, emotional regulation and impulsiveness. Such intervention is called Seeking Safety. This method was conduct therapeutically, as a clinical professional will conduct interviews to assess measurement of trauma. The first aim of this study is to provide group therapy session, where group cohesion was explored in the focus groups. Many of the participants state that being comfortable enough in the environment to share, open and get positive feedback.” (Wolf, 2012). I believe that this strategy to get women prisoners to open up and relate to one another can help reduce recidivism. That is said because this encourages women to be more open and results in improvements of their severity of social mental illnesses such as depression or anxiety they may suffer, including, PTSD from abuse. Moreover, the results show positive clinical outcomes in “females with early and complex trauma histories, substance abuse, high levels of psychiatric comorbidity, impaired functioning, and criminal justice involvement for violent offenses.” (Wolf, 2012).

It appears that group treatment to get women talking about their past experiences can help them mentally and emotionally. Not only that but the Seeking Safety initiative encourages strict compliance of their policies of attendance can help build responsibility which is needed when going back into society. Especially amongst those who have a history of adherence and compliance problems. I believe that therapy may not be a perfect treatment for women incarcerated but it is certainly headed in the right direction. Now these prisoners are able to relate to those who have been in similar situations, eliminating the isolation factors and encouraging those change their environment in order to reduce recidivism. Ultimately therapy is a very important aspect of getting to the route to prisoners simply because sentencing in itself does not impact an individuals life. The idea of locking and throwing away the key results in a reoffending. The purpose should be to try to help or reduce reoffending by providing counseling, therapy or rehabilitation.

Reference:

Afary, F. (2021, January 12). Video of Panel on Women in Prisons: U.S. & Iran. Iranian Progressives in Translation. https://iranianprogressives.org/video-of-panel-on-women-in-prisons-u-s-iran/.

Redmond, J. (2019, December 21). Military Veterans and Substance Abuse. Great Oaks Recovery Center. https://greatoaksrecovery.com/military-veterans-at-higher-risk-substance-abuse/.

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 4 Study Guide. Blackboard. [Lecture notes].

McKeown, A. (2010). Female offenders: Assessment of risk in forensic settings. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(6), 422-429. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2010.07.004

Wolff, Nancy, Frueh, B. Christopher, Shi, Jing, & Schumann, Brooke E. (2012). Effectiveness of

cognitive–behavioral trauma treatment for incarcerated women with mental illnesses and substance abuse disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(7), 703–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.06.001

Trauma on Death Row: Should Offenders Have Peace in Their Final Moments?

I decided to discuss how trauma impacts those on death row in their final moments. This is a bit of a different approach to the subject of trauma in forensic psychology, but the prison system is complex and we need to think of all angles, and it is important to analyze and understand traumatic capital punishment. I did a lot of research on this subject in my undergraduate institution, but I was not afforded the opportunity to discuss the psychology behind it. First, I want to give a brief overview of the death penalty in the United States, then I will go into more detail about the ways we can reduce trauma and botched executions. Personally, I support the death penalty because of its historical and deterrent aspect. I am not, however, a “fan” of painful deaths, like lethal injection primarily. You might think that it is strange to believe that lethal injection can be painful, but it truly is. Once I explain why, it will become more apparent.

The death penalty and capital punishment have stirred up controversy since their inception. Lethal injection in particular has become a popular topic in corrections and social justice discussions. Glossip v. Gross (2015) upheld that lethal injection cocktails that use midazolam are constitutional because they do not cause excess pain [3]. The Court (Justices Alito, Roberts, Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas) found that offenders can only challenge their method of execution if they can find a feasible alternative method. In Oklahoma, the offenders in this case were not able to provide an approved alternative. The burden of proof that the provided method would cause pain was weighed on the offender, not the state to provide, and this point was emphasized by the Court.

Since its inception, lethal injection has been thought to be the most humane method ever developed. In recent years, it has been challenged as more cases of botched executions come about. The botched executions of Clayton Lockett and Angel Diaz are recent well-known cases in the law community. Clayton Derrell Locket was executed in April 2014 in Oklahoma, when his execution by lethal injection went horribly wrong. At 38, he died of a heart attack after the lethal injection protocol failed. Witnesses recalled seeing him tense up and flinch multiple times throughout the execution [5]. It was reported that his veins had collapsed, and the staff had to use a vein in his groin area to administer the rest of the dose and complete the execution behind closed blinds in the death chamber.

Angel Diaz was executed in Florida in 2006 by lethal injection, when his execution was botched due to the needle missing the vein and injecting the execution cocktail into his soft tissue. He was awake for most of the execution and experienced chemical burns around the injection site, causing him to take more than a half hour to die while he remained in apparent pain [6]. Diaz’s skin turned black and peeled off at the burn sites. These “painful” deaths have brought the efficacy of lethal injection into question, like the cases discussed prior. Many alternative methods of execution are gaining momentum in states like Utah, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. In Tennessee, some offenders have actually been able to request another method like electrocution. Nicholas Sutton, like four other inmates before him, chose to die by electrocution in 2018 [7]. These men chose this method because of the “extreme discomfort” that could be caused by lethal injection drugs. Apparently, these inmates understand that there is a chance of regaining consciousness and that pharmaceutical companies are making it much more difficult to obtain the necessary drugs (usually midazolam, vecuronium bromide, and potassium chloride).

There have been multiple attempts to replace lethal injection with nitrogen hypoxia, a gas method where all oxygen is depleted in an enclosed chamber and replaced with nitrogen gas. This causes the offender to simply lose consciousness and die of oxygen deprivation. Bucklew v. Precythe proved that this method is not widely practiced and tested, and therefore cannot be approved as an appropriate method. Factually, many people use this method in unassisted or assisted suicides. Further research needs to be conducted to determine the efficacy of this method.

How does this tie into trauma? Humans like to feel in control of every aspect of their lives, even death if possible. Hearing horror stories from other inmates about what awaits them while on death row can lead to serious psychological issues like paranoia, major depression, anxiety, and other disorders. Feeling out of control of it all only exacerbates the issue at hand. This can make the end of the offender’s life rather unbearable and can even make them physically ill. I think a reasonable approach would be to develop a feasible program that would allow for the offender to pick his or her own method of execution. They should be able to protest lethal injection if they so choose. Though the Supreme Court ruled in constitutional and that a painless death is not guaranteed, I believe that in the 21st century, we should reassess the potential for comfortability in capital punishment and weigh the humanity of the suffering that occurs.

I used to be in favor of not “caring” about the efficacy of the death penalty, because I believed that every person who was put to death deserved to die painfully. Ever since I lost a close friend to a violent death, I have changed my stance on that. I do not believe that anyone should die painfully or violently. Obviously it seems senseless to care about whether or not someone who is sentenced to die will experience trauma or emotional distress in their final years, months, weeks, and days, and it seems a bit late to be concerned about it because it will not cause any more violence by that offender. This is not entirely true, because offenders are highly likely to lash out at other inmates and get violent if they are provoked by trauma and paranoia. Additionally, the prisons that death row offenders are placed in are unusually tough environments, which by themselves can attribute to unwanted psychological damage. We discussed in class that trauma is causal to violence, wherein offenders are much more likely to commit a crime or get violent if they have experienced trauma, as a way of coping and expressing their frustrations. Psychological care should be more emphasized in prisons, particularly on death row. Therapists and counseling should be offered more frequently and consistently for these inmates who are approaching the end of their sentence.

Sources:

[1] Amber Widgery, Karen McInnes. States and Capital Punishment, National Conference of State Legislatures, 24 Mar. 2020, www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/death-penalty.aspx.

[2] Baze v. Rees, 553 U.S. 35 (2008).

[3] Glossip v. Gross, No. 14-7955, 576 U.S. (2015).

[4] Bucklew v. Precythe, No. 17-8151, 587 U.S. (2019)

[5] Oklahoma Dept. of Corrections. “Clayton Derrell Lockett.” Clark Prosecutor, 30 Apr. 2014, www.clarkprosecutor.org/html/death/US/lockett1379.htm.

[6] Aguayo, Terry. “Florida Death Row Inmate Dies Only After Second Chemical Dose.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 15 Dec. 2006, www.nytimes.com/2006/12/15/us/15death.html.

[7] Rojas, Rick. “Why This Inmate Chose the Electric Chair Over Lethal Injection.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 19 Feb. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/02/19/us/electric-chair-tennessee.html?auth=login-google.

[8] “Ronnie Lee Gardner.” Utah Department of Corrections, Clark Prosecutor, 18 June 2010, www.clarkprosecutor.org/html/death/US/gardner1217.htm.

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2021). Criminal behavior: a psychological approach. 12th Edition. Boston: Pearson.

Rousseau, D. (2021). Study Guide. Forensic Behavior Analysis. Boston University.

The Impact of Mass Shootings on Survivors

Since August 1966, a total of 1,312 people have been killed in 187 mass shootings in the United States (Berkowitz & Alcantara, 2021). Those murdered came from nearly every race, age, religion, and socioeconomic background. However, thousands more have been injured - both physically and psychologically. Research suggests that most survivors of mass shootings show resilience, but others experience ongoing mental health problems, including post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse (Novotney, 2018). Psychologists have identified three phases of response experienced by survivors and witnesses and offer up strategies for immediate and long-term interventions. Public health, behavioral health, and emergency management professionals can use this evidence to improve their disaster behavioral preparedness plans and recovery from mass violence.

Bartol and Bartol (2021) define mass murder as “the killing [of] four or more persons at a single location with no cooling-off period between murders.” Although relatively rare, mass murders have increased in the United States over the past three decades, a reality commonly attributed to the widespread availability of guns. Following mass shootings, survivors or witnesses may go through phases where certain emotions, behaviors, and other reactions are relatively standard. According to SAMHSA (2017), these three stages of shock and healing are:

- Acute phase - characterized by denial, shock, and disbelief

- Intermediate phase - characterized by fear, anger, anxiety, transient panic, retaliatory attacks, difficulty paying attention at work or school, depressed feelings, and disturbed sleep

- Long-term phase - characterized by coming to terms with realities with alternating periods of adjustment and relapse

In the acute phase, it is most helpful to provide survivors with resources, information, debriefing, and social support. Connection over isolation has been supported by research as extremely beneficial immediately following mass shootings (Novotney, 2018). During the intermediate phase, psychologists can train the community about the importance of trauma-informed care in order to help survivors rebuild a sense of control as well as improving physical, psychological, and emotional health. If untreated by the long-term phase, behavioral health reactions (flashbacks, anxiety, self-medicating) can become mental health or substance abuse disorders that require more specialized care.

When determining which mass shooting survivors and witnesses will need long-term help, researchers point to their proximity to the incident. A meta-analysis examining post-traumatic stress symptoms discovered that those who were most directly exposed to the shooting (physically injured, saw someone else get shot, lost a friend or loved one), as well as those who perceived that their own lives were in danger, are at much greater risk for long-term mental health consequences than survivors who may have been hiding or farther from the shooting (Novotney, 2018). Prior trauma exposure and pre-existing mental health symptoms also predispose vulnerable survivors to post-traumatic stress.

Survivors’ long-term health and wellness are dependent on having strong social support systems - there is an innate human need to feel connected to their communities in the aftermath of a mass shooting. Memorial events, such as candlelight vigils, play an important role in community recovery. Continued education in schools, faith-based organizations, and recreation centers help survivors learn skills to manage their distress and enhance social connections. As Novotney (2018) so eloquently phrased it, “bringing people together to promote connections and collective healing after a tragedy is often what strengthens families and communities the most.” Survivors and witnesses of mass shootings need to know they are not alone in their pain and suffering, and that social support is crucial to coming to terms with the tragic event and reconstructing their lives.

References:

Bartol, C., & Bartol, A. (2021). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Berkowitz, B., & Alcantara, C. (2021, April 20). The terrible numbers that grow with each mass shooting. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com

Novotney, A. (2018, September). What happens to the survivors? Monitor on Psychology, 49(8). http://www.apa.org/monitor/2018/09/survivors

SAMHSA. (2017, September). Disaster technical assistance center supplemental research bulletin: Mass violence and behavioral health. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/dtac/srb-mass-violence-behavioral-health.pdf

Blog Post

Suicide is the leading cause of death among incarcerated individuals in the United States (Katsman and Jeglic 2020). This is nine times the rate of non-incarcerated adults. Some of the risk factors and explanatory mechanisms for this accumulation of maltreatment in childhood, feelings of hopelessness, and history of untreated depressive symptoms that lead to increased rates of impulsivity (Carli et. al. 2010; Wanklyn et. al. 2012; Ruch et. al. 2019; Katsman and Jeglic 2020). In a study of 1,118 incarcerated men Katsman and Jeglic (2020) found that 18% had attempted suicide at least once, and of those 51% had attempted suicide two or more times. An additional 16% had reported suicidal thoughts that they did not act upon. Additionally, they found that younger, white, divorced men were the group with the highest self-reported propensity toward suicide. Additionally, they find that those who grew up in the foster system were significantly more likely to attempt or consider suicide than those who did not. Similarly, those who reported having experience sexual abuse in childhood and those who grew up with at least one adult in the home abusing drugs or alcohol were also more likely to consider or attempt suicide. In another study, Carlie et. al. (2010) find that of their sample of 1265 male incarcerated individuals 42% report suicidal thoughts, with 13% attempting at least on time and 17% having a history of self-harm or mutilation. These men reported a history of substance use and scored higher on scales of aggression. They did not find impulsivity to be a factor.

This relates to research on juvenile offenders. Juvenile offenders who consider or attempt suicide while in custody are more likely to report physical and sexual abuse in the home, a parent or guardian who abused drugs and alcohol, and experienced a history of neglect and maltreatment (Wankyln et. al. 2012; Ruch et. al. 2019). In the case of juvenile offenders, the explanatory mechanism is related to a history of neglect and maltreatment that leads to depressive symptoms that go untreated or undiagnosed which leads to the development of low impulse control. This, when combined with incarceration, leads to feelings of hopelessness and suicidal thoughts and attempts (Wankyln 2012).

Tsopelas (2020) argues that the lack of privacy, overly rigid disciplinary tactics in prison, the constant fear of violence, and the guilt and hopelessness all lead to mental health crisis during incarceration that the prison and jail systems are unable and unwilling to focus on. From this we can see suicide prevention as an ethical issue to address in prisons.

Suicide is a major issue that is overlooked in the criminal justice literature. If suicide is the leading cause of death in the prison system, why does it get so little attention? I was interested in research this topic some because during my classes in this program, I have noticed the ethical issues of what care prisoners are entitled to come up many times. We have an attitude in this society that if someone has committed a crime, they should endure the consequences. Yet, if we treat their lives as not being important, that seems to lead to a situation where incarcerated individuals will be more likely to keep committing crimes because of hopeless and lack of other options. I think this is an issue that needs much more attention.

Cari. V. et.al. (2010). “The role of impulsivity in self-mutilators, suicide ideators and suicide attempters—A study of 1265 male incarcerated individuals.” Journal of Affective Disorders, 123(1): 116-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.119

Katman, K. and E. Jelgic. (2020). “An analysis of self-reported suicide attempts and ideation in a national sample of incarcerated individuals convicted of sexual crimes.” Journal of Sexual Aggression, 26(2): 212-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2019.1611959

Tsopelas, C. (2020). “Moral Obligation to Acknowledge and Prevent Suicide in Life Sentence Incarcerated Inmates.” European Psychiatry, 33(21). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.01.1662

Ruch, D. et al. (2019). “Characteristics and Precipitating Circumstances of Suicide Among Incarcerated Youth.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(5): 514-524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.911

Wanklyn, S. et. al. (2012),” Cumulative Childhood Maltreatment and Depression Among Incarcerated Youth: Impulsivity and Hopelessness as Potential Intervening Variables.” Child Maltreatment, 17(4): 306-317.

Self-Care Practices

Self-care is extremely important in the criminal justice field. We know that this career path is not easy but it is very fulfilling. As criminal justice professionals we are exposed to other people’s traumatic events and that can be stressful for someone to internalize. Self-care is also important to prioritize our well being to be our best selves while working our jobs.

Self care is extremely important for us as graduate students. Most of us are working full time while taking class. For me, reading has been a great stress reliever as a way to escape for a little while, I find it to be beneficial especially before I sleep. This article on practicing self - care, mentions having a buddy to keep you accountable in your self -care (Bartholomew, 2014). I think that this is a good idea in theory. It is hard if all of your friends are in other states but you could do zoom self-care sessions together. Like exercising over zoom to keep each other accountable.

I think police officers have the most stressful jobs. They interact with the mentally ill, the homeless, criminals and see individuals in crisis situations that will obviously have an impact on their own lives. If law enforcement officers do not deal with their stress or burnout, it can manifest itself into a few different ways (Fish, 2019). Some of these issues can be relationship issues, poor hygiene, nightmares, and substance abuse (Fish 2019). If we can’t take care of ourselves the way we need to be taken care of, we won’t be able to do our jobs correctly and help the public out.

Other self-care practices that could be beneficial is journaling. I like to journal just to get my thoughts out and how I’m feeling. I also like to call a friend to chat and talk about what is happening in our lives, i think getting another perspective, maybe a friend or a therapist, is always useful in my life. Even taking a walk to clear my mind I find it very peaceful and helps me relax a little bit.

Works Cited:

Bartholomew, N. R. (2014, August). Tips for practicing self-care. Retrieved April 26, 2021, from https://www.apadivisions.org/division-18/publications/newsletters/gavel/2014/08/self-care

Fish, D. (2019, August 27). How Self-Care Can Reduce Police Officer Stress. Retrieved April 26, 2021, from https://www.lexipol.com/resources/blog/how-self-care-can-reduce-police-officer-stress/

Feminism in the Penal System

Feminism in the Penal System

One topic of consideration from the class is the role of feminism in treatment options and the criminal justice system generally. Further, how new research, focused on the challenges women face in correction, has resulted in several beneficial treatment options with greater efficacy. This blog post will expand on several concepts from class, with a focus on the common thread of how the system is addressing women’s issues.

I want to further explore the field of Gender Responsive Programming. Dr Rousseau, synthesizing the work of Dr Gilligan, wrote: "women's distinct moral development results in an 'ethic of care' or a very relational way of decision making and interacting with the world. Relational theory is based on this idea that women interact with the world in an interconnected capacity. Women develop a sense of self and self-worth where their actions arise out of and lead back to connections with others. Here, theory suggests that women, more so than men, are likely to be motived by connect and relationships. For example, women are more likely to turn to drugs or to engage in drug-related crime in the context of a relationship. Women's psychological growth and health is tied to this sense of connection. Because of this, group treatment is frequently an effective strategy for women offenders" (2021, Rousseau). This is ultimately a theory based on evidence and one that is developed by mostly female practitioners in a women's prison to address the unique issues facing women. One of the best findings from this is how much more successful Group Therapy is for women than for men. And this is consistent with their theories of relational interconnectedness.

Women and children are particularly vulnerable to physical violence and unfortunately, more susceptible to trauma-related injuries. Women are twice as likely to get PTSD as men (VA, 2020). The American Psychological Association defines trauma as “an emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, rape or natural disaster. Immediately after the event, shock and denial are typical. Longer term reactions include unpredictable emotions, flashbacks, strained relationships and even physical symptoms like headaches or nausea.” (APA, 2020) The symptoms in children include phobia development, separation anxiety, sleep disturbance, nightmares, sadness, loss of interest in normal activities, reduced concentration, decline in school work, anger, somatic complaints, and irritability (APA, 2020). With the new research focusing the role of gender in susceptibility to trauma, more research should be done on ways to prevent such trauma and better ways to treat it with a focus on the new realities of the victims of trauma. It’s not just soldiers in war who get PTSD.

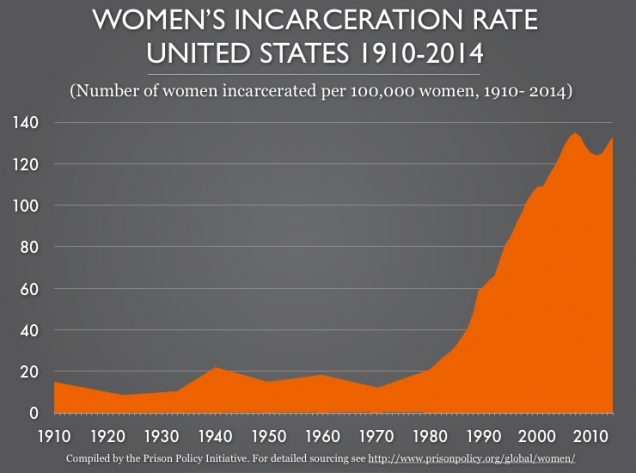

Another issue that is unique or more pronounced for women is what to do when a woman gets pregnant in prison. Naomi Riley notes in the article On Prison Nurseries that, “An estimated 6–10% of women are pregnant upon incarceration” and “are more likely to have been their child's primary caregiver before their last arrest” (Riley, 2019). Women are the fastest growing demographic to face incarceration (Goshin, 2013). Therefore, it is more important now than ever for states and the Department of Justice to have a proper solution that balances the needs of society, the mothers, and the children. Ultimately, prisons must retain their deterrent quality and should not be punishing innocent children. Criminologist Joseph Carlson was a supporter of prison nurseries. He wrote, "Many studies have shown that maternal deprivation affects children. Young children who are removed from their mothers for hospitalization or other reasons display immediate distress, followed by misery and apathy" (Carlson, 2000).

In conclusion, whether it is Group Therapy, Relational Theory, Gender Responsiveness Programming, PTSD in women, or prison nurseries, there are many developing and worsening issues that effect female populations that should be given greater consideration in research. It is one of the newest fields on criminological research. Nevertheless, it has already been incredibly fruitful.

References

APA. (2011). Children and Trauma. Accessed at https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/children-trauma-update

Bloom, B. E., & Covington, S. S. (2008). Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Women Offenders. In Women's mental health issues across the criminal justice system. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Bloom, B. E., Owen, B., & Covington, S. S. (2003). Gender-Responsive Strategies: Research, Practice, and Guiding Principles for Women Offenders. National Institute of Corrections. Retrieved from https://nicic.gov/gender-responsive-strategies-research-practice-and-guiding-principles-women-offenders

Carlson, Joseph. Prison Nursery 2000: A Five-Year Review of the Prison Nursery at the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women. US Office of Justice Programs. https://www.ojp.gov/library/abstracts/prison-nursery-2000-five-year-review-prison-nursery-nebraska-correctional-center

Gilligan, C. (1993). In a Different Voice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Goshin, L. S., Byrne, M. W., & Henninger, A. M. (2013). Recidivism after Release from a Prison Nursery Program. Public Health Nursing, 31(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12072

Riley, Naomi. On Prison Nurseries. (2019). National Affairs. https://www.nationalaffairs.com/publications/detail/on-prison-nurseries

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 4 Study Guide. Forensic Behavior Analysis. Boston University.

Vicarious Trauma and Burnout for Prosecutors and Investigators

I have been a prosecutor for almost eleven years now and I wish I could say that the job gets easier. For at least eight of those years, I have served as the child sexual assault legal advisor for my office. This role requires me not only to serve as a liaison with various agencies, including our district’s multi-disciplinary team, it also requires me to provide subject-matter expertise to other prosecutors in the preparation of their cases. This, in turn, requires me to attend various trainings and conferences to stay abreast on best practices and evidence-based research on a host of topics. Additionally, in handling internet crimes against children, I am often required to review images or videos of child sexual exploitation. In my role as a member of the multi-disciplinary team and as a prosecutor who has the final say in whether criminal charges will be pursued against a particular individual, I have often been called upon to referee disputes between law enforcement and child protective services or forensic interviewers. This is, of course, added stress on top of an already stress-filled job. I remember a conversation that I had with a forensic interviewer a few years back. I commented to her that I thought she had a tough job having to listen to kids recount the worst times of their lives every day. She replied that it was nothing compared what my job entailed. She noticed that I was puzzled by her response, so she explained. Her job requires her to listen to these children’s stories; mine requires me to do something about them and live with the consequences.

In recent years there has been a greater push among prosecutors, and lawyers in general, to educate about the dangers of vicarious or secondary trauma and burnout (Russell, 2010). Vicarious trauma has been referred to by several names, so it is important to understand the various nuances to these terms. Many are familiar with post-traumatic stress disorder as defined by the DSM-IV and later the DSM-5. However, research has also begun to focus on secondary traumatic stress, which is “the emotional duress that results when an individual hears about the firsthand trauma experiences of another” with symptoms that “mimic those of post-traumatic stress disorder” and may be “caused by at least one indirect exposure to traumatic material” (NCTSN, 2011, p. 2). Figley (1995) coined the phrase “compassion fatigue” to describe secondary traumatic stress. An individual affected by secondary traumatic stress “may find themselves re-experiencing personal trauma or notice an increase in arousal and avoidance reactions related to the indirect trauma exposure” and “may also experience changes in memory and perception; alterations in their sense of self-efficacy; a depletion of personal resources; and disruption in their perceptions of safety, trust, and independence” (NCTSN, 2011, p. 2). Vicarious trauma, though similar to secondary traumatic stress, “refers to changes in the inner experience of the [professional] resulting from empathetic engagement with a traumatized client” (NCTSN, 2011, p. 2). It is more a “theoretical term that focuses less on trauma symptoms and more on the covert cognitive changes that occur following cumulative exposure to another person’s traumatic material” (NCTSN, 2011, p. 2). Burnout, on the other hand, refers to “the psychological toll on a professional who works with challenging populations, specifically victims of trauma and abuse, which can include prolonged depression and/or anxiety, drug use, decreased desire to efficiently perform job responsibilities, diminished social activities, a desire to leave the job, or examining the meaning of life” (Hunt, 2018, p. 2). Figley (1995) cautions that burnout “emerges gradually and is a result of emotional exhaustion,” while secondary trauma or compassion fatigue “can emerge suddenly with little warning” (p. 12).

Here, I primarily want to give some practical advice for prosecutors and investigators on ways to deal with and guard against vicarious trauma and burnout. First, prosecutors and investigators should know their limits and surround themselves with a good social support team within their office that can help them spot the symptoms of secondary traumatic stress and the warning signs of vicarious trauma and burnout. This is not a lone-wolf industry, particularly when one is dealing with victims who have suffered traumatic experiences such as rape or sexual abuse. For instance, my colleagues on the internet crimes against children (ICAC) task force, who are required to review images and videos of child sexual exploitation and torture on a regular basis, are required to undergo periodic counseling sessions as a matter of policy. They also look out for one another. If you cannot trust the people you are working with to help each other with this issue, then it is time to find a new focus area. When I handled one of my first child pornography cases, I remember the investigator telling me to make sure I turned the sound off when viewing the videos. Sound is such a powerful memory trigger and it is one that does not go away quickly. For instance, my office handled a case where a husband in a drug-induced psychosis attacked his pregnant wife and attempted to cut their unborn child out of her because he believed it to be a demon. He knew something was wrong because he had called 9-1-1 prior to the attack, telling the dispatcher what he had ingested and that he was afraid that he was going to do something bad. When first responders did not arrive quickly enough for him, he proceeded to attack his wife, with the dispatcher listening the whole time. The first officer to arrive on scene overheard him asking his wife how she was still alive. After listening just to the 9-1-1 recording, I found myself unable to sleep that night. I could still hear the woman’s screams. All of the first responders in that case were required to submit to counseling.

Second, I often hear law enforcement, and some prosecutors, speak in terms of fighting against evil as if they are on a crusade. While I certainly do see my job as a calling, of sorts, it is important to not let your life or your job be defined by what you are fighting against. Instead, let it be defined by what you are fighting for. If it is defined by what you are fighting against, then you will see enemies almost everywhere. And every loss, every set-back, every struggle will eat away at you emotionally, mentally, even spiritually. If it is defined by what you are fighting for, on the other hand, then you will find much more to encourage you, to brighten your day, to make it all seem worthy. A little over a year into my tenure as a prosecutor, I was assigned a case in which both parents had been sexually abusing their four teenaged children. By the time the case came to light, the oldest had graduated high school, but the other three still had a year or two left. My team and I worked tirelessly for these kids. The youngest three were placed into foster care, which ended up being a traumatic process for them in the beginning. They were assigned to a foster family that turned out to be just as manipulative and emotionally abusive as their parents. So, we worked to get them placed elsewhere. Eventually, the parents pleaded guilty to their charges and the kids were placed in a much better environment. I can remember the day when these siblings started arguing over typical teenage sibling drama that had nothing to do with the trauma they had experienced. That, in itself, seemed like a small victory. Their foster care worker and I have stayed in touch with these kids over the years. We have watched them graduate from high school and then college. The oldest, who was too old to be placed into foster care, put herself through college, then nursing school. The youngest daughter now works with child protective services and advocates for improving conditions for other kids in foster care. I had the privilege of officiating her wedding in February. These are the moments we should be fighting for. Focusing on what we are fighting for is important in another respect: it reminds us not to lose the child just to win the case. While some prosecutors may disagree with me, I will not force a traumatized child to do what he or she is not ready to do, including testifying at trial. I will work with the child’s therapist to get them ready for court, but in the end, if the child is not ready or is not in a place emotionally or psychologically to endure the stress of trial, I will not force them to do so. I will try work out an acceptable plea agreement as best I can, but I will not re-victimize or re-traumatize a child for the sake of winning a case.

Lastly, learn to focus on the good in this world, not just the bad. If all we focus on is the negativity and stress that surround us, it will leave us depleted in the end. Learn to find healthy outlets or hobbies that allow you to see the good in other people. Being prosecutor or an investigator frequently exposes you to bad people doing bad things on a daily basis. It is easy to become jaded and lose objectivity. Overtime, this will eat away at you like running water to a boulder. For me, it is my commitment and service to my church that allows me to see the good in this world. It allows me to see people change. It allows me to see good people and not-so-good people do good things. It gives me a balance in my life. A few years ago I prosecuted a gentleman for drug possession and he was given a probated sentence. He struggled with his addiction during his probationary period and had to serve a few stints in jail as a result. Eventually, he started working with a small business that installs commercial playgrounds. As it turned out, the owner of that business attended the same church as me and started filling me in on his progress. Eventually, he started attending church with us. He has really turned his life around thanks to this couple and he even still comes to me to admit when the temptations to return to his addiction comes around again. He wants that accountability. I have seen his life changed and it gives me hope in others as well. I understand, religion is not everyone’s cup of tea, but we far too often ignore the spiritual side of humanity. So, if yoga or some other form of meditation works for you, go for it. In the process you will find even more people to support you emotionally, psychologically, spiritually, and mentally. Remember, this is not a lone-wolf profession.

References:

Figley, C.R. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. NY: Brunner/Mazel.

Hunt, T. (2018). Professionals’ perceptions of vicarious trauma from working with victims of sexual trauma [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7158&context=dissertations.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) (2011). Secondary traumatic stress: A fact sheet for child-serving professionals. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources/fact-sheet/secondary_traumatic_stress_child_serving_professionals.pdf.

Russell, A. (2010). Vicarious trauma in child sexual abuse prosecutors. Center Piece 2(6). Retrieved from https://www.zeroabuseproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/39255836-centerpiece-vol-2-issue-6.pdf.

911 Dispatchers

Trauma within law enforcement is talked about often along with how to combat the stresses faced on a daily basis. First responders stereotypically consist of medical personnel, police, fire, corrections and the military. A handful of states have recently passed legislation to include 911 dispatchers in the first responder classification due to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that is commonly diagnosed in the field. “According to the DSM-5, the essential feature of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is “the development of characteristic symptoms following exposure to one or more traumatic events” (American Psychiatric Association)

Dispatchers spend 10 hours a day answering your calls for help on what is possibly the worst day of your life. They hear the tremble in your voice as you hide while someone is breaking into your home; they hear your screams while you try to revive your family member or friend after they have been injured or killed; they hear your cries when your infant stopped breathing or your mommy and daddy are physically fighting; they play detective by pinpointing your location with nothing but screams in the background or while you were stranded on the river; and they have talked you out of suicide until help arrived. The amount of trauma faced by local dispatchers is enough to stoke fear, anger, distrust, and mental fatigue.

In module 3 of Forensic Behavior Analysis, the notion that forensic psychologists may have an allegiance to an agency or patient, is not limited to forensic psychologists. Many dispatchers face their own personal fears, through someone else, every day, and even several times a day. As a former dispatcher, I often felt an allegiance to the caller I was trying to help. Their safety was my priority as long as I was in contact with them. Once law enforcement arrived on scene, the officer’s safety became my priority and I had an allegiance to them, to protect them and guide them.

There are many risks that factor in to how PTSD will affect a dispatcher. For example, a dispatcher who has experienced sexual trauma at some point in their life will, in fact, take a sexual assault 911 call during their career. Calls like this often-led dispatchers to comfort the victims and cater to them versus building that barrier that is needed. “While the protocols can be useful for guiding dispatchers through stressful situations, in other circumstances, they can cause pain and discomfort when a dispatcher can tell that a situation is hopeless. Dispatchers are not trained to deal with each unique case differently; they are expected to follow through with the routine questions regardless of circumstances” (Muller, 2017). In many cases, the situation is helpless and all the dispatcher can do is keep the caller calm until help arrives. This feeling, alone, is enough to bring a dispatcher to their lowest point.

In an effort to promote self-care, law enforcement agencies have become increasingly aware of the trauma their personnel face and provide one-on-one counseling, group therapy and a healthy number of vacation hours each month. But to be honest, I don’t know a single dispatcher that doesn’t love going to work each day and helping the community they serve.

References

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth). (2013). American Psychiatric Association.

Muller, R. T. (2017, September 21). Trauma Exposure Linked to PTSD in 911 Dispatchers. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/talking-about-trauma/201709/trauma-exposure-linked-ptsd-in-911-dispatchers.