CJ 720 Trauma & Crisis Intervention Blog

Ketamine Infused Therapy for PTSD

Ketamine Infusion Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Written By Cady Balde

Over the last two decades, the anesthetic drug ketamine has become a popular new treatment approach for mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Derived from the psychedelic drug phencyclidine, commonly known as PCP or angel dust, ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic. Legally, ketamine is a F.D. Ketamine is an approved anesthetic that is commonly used in emergency rooms; however, when used recreationally, it causes mind-altering effects that are described as a "separation of mind from body even as the mind retained consciousness" (Witt, 2021). With regard to illicit drugs and human subject research, purposefully inducing these hallucinogenic properties has raised controversy within the clinical and psychiatric realms. However, in 2006, the National Institute of Mental Health, along with Yale clinician Dr. Gerard Sanacora, found schizophrenic patients experienced mood improvement after receiving a single intravenous dose of ketamine.

Patients who suffer from major depressive disorder, chronic stress, or PTSD experience synapse loss. Synapses are wire-like signals that regulate our brain's responsibility for behavior, mood, and cognitive function. Neurotransmitters such as cortisol, dopamine, and serotonin are brain chemicals that signal danger in our bodies. However, when an individual experiences a traumatic event, these chemicals become imbalanced due to the brain synapses thinking they are in a constant fight-or-flight situation. Ketamine therapy, administered intravenously, has shown promise in re-growing lost synapses. Chief Psychiatrist at Yale-New Haven Hospital, John Krystal, identified that "within 24 hours of a person’s first dose of medically supervised ketamine, those lost connections start to regrow. The more synapses they grow, the better the antidepressant effects of ketamine are for them" (Collins, 2022). Dr. Krystal did note that ketamine therapy should not be used as a sole treatment plan but should be used in conjunction with anti-depressant medication and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

A possible limitation of ketamine infusion therapy is the increased risk of psychosis due to its hallucinogenic effects and the possibility for individuals to develop drug dependence. However, I found ketamine infusion therapy overall to be an effective new treatment approach for those with medication resistant depression and treatment resistant PTSD.

References

Witt, E. (2021, December 29). Ketamine Therapy Is Going Mainstream. Are We Ready? The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-inquiry/ketamine-therapy-is-going-mainstream-are-we-ready

Collins, S. (2022, May 4). What is Ketamine? How it Works and Helps Severe Depression. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/depression/features/what-does-ketamine-do-your-brain

Warnings signs for suicide in the workplace

The holiday season can be a time of great joy, social support, gifts, and nostalgic traditions. However, the holidays can also be a challenging time for many people, being reminded of their grief and loss, effects of seasonal depression, and end of the year reflections. Some people might feel extremely joyous and hopeful for the new year, and some might feel great anxiety and hopelessness.

In this post, I want to share warning signs for suicidality that may show up in the workplace. Employees that are often sad. There may be changes in the appetites, extreme weight gain or weight loss, and they might be more agitated over time. A decrease in productivity could be an indicator of other issues. Some employees may have trouble concentrating, remembering things, and following through on tasks, and this may be a change in their regular work behavior. You might notice employees having a lot less energy, expressing changes in sleep patterns, showing up late, or not keeping up with their appearance in the same way. They may potentially come to work less, calling out sick, or not attending events as they used to. On the more dangerous spectrum, employees may be under the influence of drugs or alcohol at work and they may even just express thoughts or comments about suicide.

If you are a supervisor or another employee seeing these changes in someone you work with, I would encourage you to approach their behavioral changes with curiosity instead of judgment. An example could be “Hi, I just wanted to check in and see how you’re feeling or if there is any way I can help. I’m noticing that your tasks are being completed late when you used to complete them early.” Also, maintaining confidentiality. If any information is shared, sharing with the proper people in the workplace who can help provide necessary care. It would not help for someone’s mental distress to become workplace gossip. Lastly, reach out to people who can help. Encourage the employee to utilize appropriate hotlines, ask Human Resources for accommodations, or use EAP benefits to get mental health treatment. Don't feel that you have to manage someone’s suicidality alone.

988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline

Goel, C. (2022, August 8). Top 7 employee suicidal warning signs . Axiom Medical. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://www.axiomllc.com/blog/employee-suicidal-warning-signs/

When Routine Workplace Stress Is More Than Routine and More Than Stress – Secondary Trauma, First Responders, and the Case of Jeffrey Reynolds

October 23, 2012 started out like any other day for me at my office in Livingston, Louisiana. I had only been a prosecutor for a little more than two years and was expecting another quiet day in the office. Sometime that afternoon a police officer came by my office to drop off paperwork and informed the receptionist that there was a bad case developing in the City of Walker. The officer informed the receptionist of what he knew about the case and left. A few minutes later, the receptionist came to my office and informed me that a woman had been stabbed by her husband, killing their unborn child. She also informed me that she thinks the woman was a victim on one of my domestic violence cases. I decided that I would walk over to the Detectives Division of the Livingston Parish Sheriff's Office to gather more information. Speaking with one of the detectives, whom I know well, he apprised me of what was going on and we were able to figure out that this case was unrelated to anything my office was currently prosecuting. He also played me the 911 call of this dreadful incident. I will say, at this point, hearing the screams of this woman as she was being attacked by her own husband was traumatic in itself, but hearing the full details of what all transpired has left an indelible mark in my memory and in my career as a prosecutor. Still, what I experienced was nothing compared to what this woman was made to endure and what the first responders witnessed as they came on scene.

On that date 31-year old Jeffrey Reynolds ingested some sort of synthetic marijuana, which he claimed produced a hallucinating effect on him and led him to believe that the fetus inside of his wife Paula, who was 8 months pregnant, was actually a demon (Gaulden, 2015). Reynolds called 911 to tell them that he had ingested synthetic marijuana and that he was afraid that he was about to do something bad and they better send someone to stop him (Gaulden, 2015). While on the phone with 911 and while seeming very calm to the operator, Reynolds proceeded to grab a pairing knife, slash his wife's throat and proceed to attempt to cut the fetus from her womb (Gaulden, 2015). Paula Reynolds can be heard on the 911 call screaming as the attack first takes place and then yelling, "I'm dying! I'm dying!" (Gaulden, 2015). Reynolds can also be heard asking his wife why she is not dead yet. When first responders first arrived and observed the gruesome scene, some immediately apprehended Reynolds, one swaddled the child though it was clearly dead from a knife cut across its head, while others tended to Paula. None of these first responders would ever be the same. Sheriff Jason Ard agreed to have his department pay for counseling for all law enforcement, firemen, coroner's investigators, and medical personnel that were on scene that day.

Though he continues to blame a drug-induced psychosis for his actions that day, Jeffrey Reynolds was charged with and later pled to 15 years for the attempted second degree murder of his wife and 20 years for the first degree feticide of his child "baby Isaac" (Hardy, 2015). There were many who were upset with my office's decision to accept this plea deal. Unbeknownst to the general public and even misunderstood by many of the officers involved with this case, there was a legal technicality that may have resulted in no conviction at all or perhaps a finding of not guilty by reason of insanity. While Louisiana law states that voluntary intoxication is not a defense to any crime, it does vitiate specific intent. Both attempted second degree murder and first degree feticide require prosecutors to prove that the defendant acted with specific intent. Furthermore, a divided sanity commission could not agree whether Jeffrey Reynolds suffered from a drug-induced psychosis, such that he was deprived of the ability to distinguish between right and wrong, and therefore not guilty by reason of insanity. While we had very little doubts that a jury would find him guilty, this plea deal was, in effect, a compromise to avoid lengthy appeals that would not only re-traumatize Paula and her family, but also run the risk of an appellate court overturning the conviction on these legal grounds altogether. Though I was not the prosecutor in charge of this case, all of us in the office agreed with the decision; as did Paula and her parents.

While the criminal case may be over, the trauma inflicted that day has had a ripple effect that continues to this day, not only for Paula, who has since divorced her husband and remarried, though she still bears the scars (physically and emotionally), but also for the first responders who witnessed the horrors of that day. I have a hard time calling the trauma they experienced "vicarious" or "secondary," as if that somehow lessens the reality of what they went through. It is said that vicarious trauma "occurs when someone experiences a crisis secondhand" (Marin, 2021). Quoting Susan Ferrin, founder and executive director of First Responders Resiliency, Inc., Kate Marin (2021) writes in her blog: "'Research indicates that when you're exposed to things that are traumatizing to your brain, your brain spends an enormous amount of energy trying to sort it out, trying to make sense of it, trying to create reasons for this kind of thing.' This process is exhausting, particularly when an individual is emotionally invested in the people and events they work with." This is at the heart of vicarious trauma, particularly with criminal justice professions. While being a first responder is an inherently stressful occupation, including for law enforcement, when these routine work environment stresses are combined with traumatic experiences, the risk of developing PTSD symptoms increases (Maguen et al., 2009). While the first responders who came on that traumatic scene in October 2012 may have learned to deal with their experience and relieve any PTSD symptoms they were suffering, I know personally that they are still trying to understand why this happened emotionally, maybe even spiritually. While I doubt that I have been able to give to them a satisfactory answer, I have never let them doubt my support for them. So, keep the faith brothers and sisters and keep up the good fight. There will be more Paula's out there that will need you to hold their hand in their darkest hour. Just make sure there are people in your life who are there to hold your hand as well.

References:

Gaulden, T. (2015, Sep. 18). 911 call details brutal feticide attack. WBRZ Channel 2 News. https://www.wbrz.com/news/911-call-details-brutal-feticide-attack/

Hardy, S. (2015, Sep. 23). Livingston Parish man pleads no contest in feticide case; cut unborn child from wife's body while high on synthetic marijuana. The Baton Rouge Advocate. https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/communities/livingston-parish-man-pleads-no-contest-in-feticide-case-cut-unborn-child-from-wife-s/article_6352ade9-6f16-593f-9a08-33804bbb31b4.html

Maguen, S., Metzler, T.J., McCaslin, S.E., Inslicht, S.S., Henn-Haase, C., Neylan, T.C., & Marmar, C.R. (2009). Routine work environment stress and PTSD symptoms in police officers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(10), 754-760. doi:10/1097/NMD.0b013e3181b975f8.

Marin, K. (2021, Aug. 20). Vicarious trauma: Understanding traumatic stress in first responders [Blog]. Perimeter Platform. https://perimeterplatform.com/vicarious-trauma-understanding-traumatic-stress-in-first-responders/#:~:text=Experiencing%20vicarious%20trauma%20as%20a%20first%20responder&text=This%20process%20is%20exhausting%2C%20particularly,than%20to%20work%20through%20them.

Practicing Self-Care After Trauma

Trauma can have devastating effects on the body and mind; physically, trauma can cause lethargy, exhaustion, fatigue, and racing heartbeats, among others; emotionally, trauma can cause anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and dissociation, among others. In the aftermath of a traumatic event, one of the most vital things one can do for oneself is practice effective self-care strategies. The traditional forms of care and support for survivors include cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectic behavior therapy, EMDR therapy, and prolonged exposure therapy. In addition to these therapies, self-care strategies that survivors should practice outside of treatment are also essential to aid in the healing process.

Utilizing self-care strategies can help trauma survivors heal in a variety of ways:

- Breathing exercises: Several breathing exercises can calm an individual when experiencing a stressful situation or flashbacks. The applications "Calm" and "Headspace" are excellent for beginners interested in using breath work to relieve symptoms.

- Journaling: Writing down thoughts and feelings is a great way to safely express one's emotions and feelings. Trying to suppress feelings and emotions will ultimately result in an even more intense outburst; regardless of how hard you try, those emotions will eventually surface. Journaling can provide insight into why and how the individual is experiencing the feelings they are experiencing, as well as being a very introspective experience. It's also helpful for assessing situations and coming up with solutions.

- Physical self-care: Taking a hot or cold shower, applying a face mask, and exercising are excellent self-care strategies. By taking a hot shower, you can stimulate the release of oxytocin in the brain. In contrast, a cold shower and exercise will produce endorphins responsible for boosting happiness and reducing stress. Cold conditions also stimulate the vagus nerve, which regulates internal functions that promote calmness and clarity by slowing down the sympathetic nervous system and activating the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Spirituality: Practicing gratitude, breath work, meditating, yoga, manifesting, and self-reflecting can be powerful tools to foster a new sense of being, leading to a better quality of life. Spirituality has been a vital part of my life for the past few years.

- Healthy eating habits: Eating unprocessed whole foods is the key to fostering a healthy body and mind. There is a direct link between our gut microbiome and our mental health. Instabilities in our gut flora can lead to various health issues, including brain fog, depression, and anxiety. It is possible to alleviate those symptoms by improving gut health. There should always be a balance; it's essential not to restrict oneself, and occasionally indulging is fine. Maintaining a healthy relationship with food can be difficult, but it is necessary for our mental well-being.

- Goal setting: Goal setting and creating a plan for the future is a great way to stay focused and excited about the future. During times of distress, focusing on the positive aspects of life can be difficult. It is helpful to remain present when one is working toward a goal.

- Music: Music is an essential source of comfort when facing mental challenges. It is an excellent form of self-care and helps to relieve trauma and negative emotions. It's a great way to express feelings and improve your mood and mind.

We all find it difficult to remember to take care of ourselves. Trauma can exacerbate these difficulties, making it easy to fall into a vicious cycle of self-destruction. In addition to more traditional forms of therapy, these self-care strategies are incredibly beneficial for healing trauma and promoting long-term recovery.

References

Self-care after trauma. RAINN. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://www.rainn.org/articles/self-care-after-trauma

Self-care after trauma. RAINN. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://www.rainn.org/articles/self-care-after-trauma

Self-care for PTSD. Mind. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd-and-complex-ptsd/self-care/

An Unspeakable Horror

Traumatic flashback or stroke?

In her book, “Trauma and Recovery”, Dr. Judith Herman writes that, “remembering and telling the truth are two essential steps in the process of recovery”. Yet the neurobiological impact on the brain makes it nearly impossible for an individual to speak during or after the effects of a traumatic flashback. The phenomenon of a traumatic flashback operate as a vivid experience in which an individual is exposed to reliving some aspects of the traumatic event in the now. The composition of a traumatic flashback is said to be experienced as if watching a highlight reel of what happened but does not necessarily portray seeing images, events, and sensations in a chronological narrative.

An individual experiencing a traumatic flashback may experience any of the following:

- Seeing full or partial images of what happened

- Noticing sounds, smells or taste connected to the trauma

- Feeling physical sensations, such as pain or pressure

- Experiencing emotions that were felt during the trauma

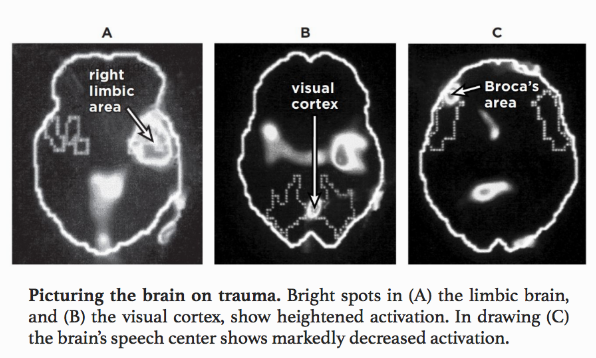

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, author of the critically acclaimed book, “The Body Keeps the Score”, recites results from a patient who was being medically observed at the time of their physiological reactions during a traumatic flashback. Van der Kolk expresses that the moment they turned on the tape recorder to play back an auditory narrative similar to the patient's traumatic experience, the patient’s heart began to race, and their blood pressure jumped immensely (van der Kolk, 2015). The sole exposure to hearing something remotely related to their trauma, despite occurring 13 years prior, activated specific areas of the left frontal lobe cortex of the brain, also known as Broca's area. The Broca's region is responsible for the functionality of speech and is often detrimentally affected in patients who have suffered from a stroke, an instance in which the blood supply to the brain region is cut off. Without the proper functioning of Broca's area, an individual is unable to emphasize their thoughts or feelings into words. The finalized results of the patient’s scan illustrated that Broca's area went off-line whenever a flashback was triggered. Highlighting the notion in which the effects of trauma are not necessarily different and can overlap with the effects of physical lesions like strokes (van der Kolk, 2015).

The holistic experience of trauma is curated through a variety of physical manifestations in the body. Even years later, individuals who have experienced trauma have enormous difficulty re-telling their story. A traumatized persons bodily composition becomes completely rewired and plagued with overwhelming emotions such as terror, rage and helplessness. The medical correlation between the physical complications of a stroke and the experience of a traumatic flashback is not to be understated. Strokes' effects on the body are often severe, similarly leaving an individual paralyzed or with the inability to speak for the remainder of their lifetime. Understanding the interplay between this phenomenon and the effects of trauma definitively highlights the intersectionality in which traumatic incidents have the ability to completely rewire the body's autonomy and in the worst cases, permanently.

References

Herman, J. (2015). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Music Therapy For Trauma

For this blog post I am going to be looking at a treatment approach for PTSD that was not mentioned in the modules or readings. However, I believe that this approach uses very similar concepts as approaches we have explored in the course. The treatment approach I will be focusing on is music therapy, specifically for individuals who suffer from PTSD or childhood trauma. Music therapy can be implemented in two different ways: passively or actively. Passive music therapy is the act of listening music to relax, improve mood or allow the listener to focus on something else besides a difficult or triggering memory (Robb-Dover, 2021). Active music therapy on the other hand is the act of creating music to relax or process negative emotions or memories (2021). In this post I will discuss these two different approaches to music therapy for trauma survivors and the concepts from the course that they have in common. I will also discuss some of the limitations and criticisms of music therapy as well as my personal thoughts on the approach.

Active music therapy, especially the actions of singing a song or singing along in a group can be very therapeutic for trauma survivors. Singing can create a sense of social reciprocity because it relies on being connected to the rhythm and lyrics of a song and to sing at the same time as others in a group (Hussey et al., 2008). Singing can also allow an individual to process trauma and re-contextualize it in a musical setting. For example, if an individual relates strongly to the lyrics of a particular song, singing this song can create an emotional outlet and a safe space to process trauma (Steward, 2018).

Passive music therapy allows listeners of music to momentarily lose a sense of time, space and even personal identity while maintaining an overall sense of being and feeling (Sutton & De Backer, 2009). This also allows listeners to process their trauma in a different context than originally experienced which can allow for growth and resilience. After hearing music or musical stimuli, a therapist can guide the listener through processing what they have heard and connecting it to personal experiences. While this process allows individuals to be mindful of musical patterns, it can also increase mindfulness of feelings and stimuli in the real world. Therefore, music therapy is often paired with cognitive behavioral therapy (Hussey et al., 2008).

Both approaches use theories that we have discussed throughout the course. Specifically, the fact that trauma affects neurobiological processes, especially those that recognize stimuli and discriminate between threats and non-threats (Rousseau, 2022). Dr. Van Der Kolk stated that this trauma is encoded in the brain as a physical sensation and becomes difficult to express vocally or verbally (2015). PTSD sufferers are also much more sensitive to dopamine reception which can leave them at risk of developing substance use disorders (Brodnik et al., 2017). Music allows a dopamine releasing activity that is much healthier than using controlled substances and can even promote the creation of new neural pathways that are necessary for healing from trauma (Bronson et al., 2018).

Music is of great interest to me as an area of study which I got to explore in some of my undergraduate courses. It is also of great personal interest to me as I play multiple instruments and my mother is a music teacher. Music for me has been a great source of both relaxation from stress and social connection by listening to or playing music in groups. The biggest obstacles of this approach from my perspective are lack of structure across approaches and the risk of exposure to inadvertently triggering stimuli. Lack of structure because becoming a dedicated music therapist is very difficult and creating personalized approaches to care for this type of therapy is very important. Therefore, if an individual is simply exposed to music or tasked with learning how to create music in an unstructured format, they are at risk of either becoming discouraged or even further traumatized by the stimuli around them.

Sources:

Brodnik, Z. D., Black, E. M., Clark, M. J., Kornsey, K. N., Snyder, N. W., & España, R. A. (2017). Susceptibility to traumatic stress sensitizes the dopaminergic response to cocaine and increases motivation for cocaine. Neuropharmacology, 125, 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.07.032

Bronson, H., Vaudreuil, R., & Bradt, J. (2018). Music therapy treatment of active duty military: An overview of intensive outpatient and longitudinal care programs. Music Therapy Perspectives, 36(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/miy006

Gooding, L. F., & Langston, D. G. (2019). Music therapy with military populations: A scoping review. Journal of Music Therapy, 56(4), 315–347. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thz010

Hussey, D. L., Reed, A. M., Layman, D. L., & Pasiali, V. (2008). Music therapy and complex trauma: A protocol for developing social reciprocity. Residential Treatment For Children & Youth, 24(1-2), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865710802147547

Robb-Dover, K. (2021, November 3). How music is therapy for PTSD and other mental illnesses. FHE Health – Addiction & Mental Health Care. Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://fherehab.com/learning/music-therapy-ptsd-mentall-illness#:~:text=Music%20therapy%20for%20PTSD%20can,positive%20part%20of%20self%2Dcare.

Rousseau, D. (2022). Trauma and Crisis Intervention

Stewart, K. (2018). All roads lead to where I stand: A veteran case review. Music and Medicine, 10(3), 130. https://doi.org/10.47513/mmd.v10i3.621

Sutton, J., & De Backer, J. (2009). Music, trauma and silence: The state of the art. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(2), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2009.01.009

CTE and Law Enforcement

Growing up in high school, one of my favorite movies was Concussion, which covers the issues of concussions, CTE and their effects on players in the NFL. When we started talking about the brain functions and how they correlate to traumatic events, I found some research that discussed how law enforcement can suffer from CTE as well. Understanding the long term effects of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) in law enforcement can help with strategies of improving officer mental health in the long run. CTE is a degenerative brain disease that is usually found in people who have suffered from concussions or other hits to the head which trigger a protein, Tau, to form in the brain. The protein, Tau, can deteriorate brain tissue which usually results in the individual suffering from side effects such as memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, impulse problems, aggression, suicidal tendencies, dementia, etc. When we talk about CTE its usually regarding professional athletes and military personnel, there is not much of a discussion regarding law enforcement personnel.

Technically, the only way to see if someone has suffered from CTE, is performing an exam on that person’s brain after they have died to see if the protein, Tau is present. When we think of people constantly hitting their heads or being a part of blasts, we think of athletes and military personnel. However, SWAT members experience exposure to low-level blasts, as well as law enforcement personnel can experience different exposure to gunshots from training and in the field. Subsequently, law enforcement personnel could be suffering from CTE, however it is going by undedicated and instead thought as PTSD.

CTE does need to be studied more inside the law enforcement community to see how the rates of it are impacting law enforcement. We are aware that law enforcement personnel suffer from mental health issues and that they struggle with reaching out for help. There are different interventions that can be made if CTE is more established as an issue. This includes medical interventions, critical incident management teams, and training/education to law enforcement. Medical interventions could include assessing who in law enforcement is more at risk of developing CTE. For example, in Florida a bill was passed in 2018 that basically established that for under certain circumstances, a first responder can medically retire under workers compensation for a PTSD diagnosis. Implementing a critical incident management team would be highly impactful to assist officers when they suffer from a traumatic event. It can remove the stigma surrounding asking for mental health therapy while also serving as a look at who could be showing early signs of PTSD and CTE. Lastly, educating officers on signs of PTSD and CTE could be greatly impactful on their awareness for themselves and their fellow officers. There are plenty of situations in this field where you could be exposed to PTSD or CTE and raising awareness of that could save officers lives. Overall, acknowledging the risk of CTE in law enforcement could reduce the number of officer suicides, not to mention self-destructive behavior that officers can develop and ruin not just their life but their families lives as well.

Reference:

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 6: Trauma and the Criminal Justice System

Walsh, M. (202, August 4). What is the prevalence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in law enforcement? Police1. Retrieved December 12, 2022, from http://www.police1.com/treatment/articles/what-is-the-prevalence-of-chronic-traumatic-encephalopathy-cte-in-law-enforcement-xdFEAJObPoByLM9y/

Our Bodies Reactions to Childhood Trauma

By Krystle Ramdhanie December 12,2022

*Warning* May contain some triggering information*

A time in our lives when we are in our most innocent stage of our life, our childhood. Most people hear the word childhood and think of all the wonderful memories like riding their first bicycle, ice cream trucks, birthday parties, playing in the snow or a fond memory of an activity with a parent that replays in their minds when they see or smell something familiar. Then there are some of us who hear the word childhood and we completely have a blank thought, our stomachs began to twist a bit, or we start to feel nervous, anxious, or angry. This is because CDC research shows more than 60 percent of American adults have as children experienced at least one ACE (Adverse Childhood Experience), and almost a quarter of adults have experienced 3 or more ACEs, likely an underestimate. Childhood or early childhood trauma can occur in many different forms from physical or sexual abuse, witnessing a traumatic event, witnessing domestic violence, bullying, mental abuse, and sometimes situations like refugee trauma or natural disasters. As children we often are unable to fully process what is happening to us, especially in cases of physical, mental or sexual abuse we tend to blame our selves as children or convince ourselves that the person did not mean to do it to us. As we develop and grow into adults our brains block out these horrific event until we are reminded of them in some way as adults. How does this trauma affect our bodies, well our bodies and our brains are built to protect us from imminent danger, we call this the fight or flight response where our brains release stress hormones like epinephrine, cortisol and adrenaline in response to it. The effects of childhood trauma can last well into our adulthood and effect our health and lifestyles choices. There is a higher likelihood of developing chronic illnesses in adults because of the trauma they experienced as children, they are more likely to engage in high-risk activities, poor dieting and more likely to develop depression. "Exposure to trauma during childhood can dramatically increase people’s risk for 7 out of 10 of the leading causes of death in the U.S.—including high blood pressure, heart disease, and cancer—and it’s crucial to address this public health crisis, according to Harvard Chan alumna Nadine Burke Harris, MPH ’02." Trauma puts so much strain on our bodies as we internalize the pain and events that happened to us as children. As this trauma is stored in our bodies it releases hormones at higher than normal levels that begin to impact our mental and physical health. Headaches, upset stomach, muscle tension, and fatigue are just a few of the other things that happen to our body as we store trauma in it. Research has proven that children who experienced severe trauma such as verbal, physical or emotional abuse or lived with drug or alcohol abusers were 50% more likely to develop cardiovascular disease later on in life than those who had low exposure to childhood trauma.

But why just blog about how trauma affects our bodies, while taking this course I began to face a lot of my own traumas. At the beginning of it I became very ill and was sick for weeks trying to recover but it just felt like my body would not bounce back from this illness. The more I read the more I realized that maybe because of the trauma I had experienced as a child and not properly facing it, I myself developed all these other physical health issues. Compromised immune system, hypertension, chronic migraines, sleeping disorder, eating disorder, heart palpitations and several autoimmune diseases, and depression are just some of the things I battle with daily. I grew up in Roxbury, an inner city town that people referred to as "the ghetto", young parents who barely knew what they were doing but trying to survive, I encountered my first trauma when I was just 4 years old. An older male cousin you molested me for 3 years until my parents moved to another part of Roxbury, and when I thought I had finally gotten away from the pain of that my father began using drugs and physically abusing me to punish my mom when she didn't give him money to support his habits. There were nights I would just pray to die and other night I would just forget about what happened, but after reading The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van Der Kolk, I started remembering about nights when I would get beat and I would go to the bathroom and stick my fingers down my throat to vomit just so I would forget the pain from the belt. I realized that in fact these health issue were indeed a direct response to my trauma. Van Der Kolk says “As long as you keep secrets and suppress information, you are fundamentally at war with yourself…The critical issue is allowing yourself to know what you know. That takes an enormous amount of courage.”. The more trauma we suppress the more danger we put our bodies through, our minds begin war with our bodies and lead to dangerous outcomes.

There are ways to prevent this from taking over your life and healing from the trauma. Therapy is at the top of the list, starting it as soon as possible is the best. Working through traumatic events with a therapist helps your body and brain understand and process the memories of your trauma. Practicing calming techniques or mindfulness practices like yoga, meditation or breathing exercises help with decreasing your anxiety and redirecting negative thoughts around your trauma. Establishing healthy lifestyles like introducing exercise routines, better sleeping habits, avoiding alcohol and drug consumptions also help your brain rewire giving you space to slowly process all you have been through. Working these into our lives help us find a way to make peace with the trauma we are at war with and helping our bodies recover to live longer and healthier lives.

“The essence of trauma is that it is overwhelming, unbelievable, and unbearable. Each patient demands that we suspend our sense of what is normal and accept that we are dealing with a dual reality: the reality of a relatively secure and predictable present that lives side by side with a ruinous, ever-present past.”

― The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma

https://www.heart.org/en/news/2020/04/28/traumatic-childhood-increases-lifelong-risk-for-heart-disease-early-death

https://www.cdc.gov/washington/testimony/2019/t20190711.htm#:~:text=CDC%20research%20shows%20more%20than,likely%20an%20underestimate%5B5%5D%20.

https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/childhood-traumas-devastating-impact-on-health/#:~:text=Exposure%20to%20trauma%20during%20childhood,Burke%20Harris%2C%20MPH%20'02.

https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/features/emotional-trauma-mind-body-connection

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Genocide, Slavery, and the Traumatic effects on the African American Community

It can be extremely difficult, as a black person, to reflect back on the atrocities that have taken place such as slavery on African American people in our country. The outrageous monstrosity of what has occurred and has been afflicted on the African American race for many, many years imprinted trauma in a ways that can not be removed. There are ways my people and I have been traumatized by the memories and are still having to navigate through injustices that still happen systemically in our Justice system. Police shootings, mass incarceration and even unfair opportunities when it comes to employment.

That said, my community still has more to work to do. At times I feel that we fall in line with what has been norm to us and don't take a stand on the mistreatment that is handed to us. Like the Reserve Police Battalion 101, discussed in our course readings, I have realized that although genocide was happening via Holocaust, these soldiers ended up overlooking, because of the trauma endured, ordinary men became murderers.

Aryanne

Service Dogs Blog Post

For my blog post, I chose to further my previous post on the therapeutic approach of having a service dog to help address trauma. The therapeutic approach to addressing the impact of trauma that I originally chose was service dogs. The purpose of having a service dog for someone with trauma is to help aid them in times where the owner's symptoms prevent them from being able to do a task. For instance, some of the more basic services that these dogs can provide are, "to guide a disoriented handler, find a person or place, conduct a room search, signal for certain sounds, interrupt and redirect, assist with balance, bring help, bring medication in an emergency, clear an airway, and identify hallucinations" (Rousseau, 2022). Service dogs not only help people with PTSD, but can help people with all different types of disorders, whether from trauma or other similarly mentally altering experiences. They are also commonly used for people who are blind, for those who have seizures, and for those with severe anxiety, from what I have witnessed.

Some people prefer to have their service dogs where a vest, so that people do not try and pet or distract the dog from doing its task (servicing his/her owner). These vests tend to say things like "working dog", "do not pet", or "service animal", etc. in hopes that people will leave the animal be while it is actively working. It is crucial that service dogs stay completely focused on their task while they are "on duty". However, some people have used the term "service animal" lightly and as an excuse to be able to bring their dog(s) from home and into stores with them. This could especially be concerning if the fake service dog reacts to the real service animal, and in turn, distracts the service dog from staying focused.

Although service dogs are great for aiding people with trauma, they are in no way capable of completing relieving one of the symptoms that they experience. Unfortunately, none of the therapeutic approaches addressing trauma can guarantee to completely cure someone of their trauma, but they most certainly can help a great deal. Overall, these dogs focus on ways to support their person before, during, and after a trigger may occur. In some instances, a service dogs actions could be the difference between life or death for someone who cannot get the help for themselves. Service dogs are very effective for many people who have trauma, and they can make for a great therapeutic approach in addition to other forms of therapy.

As mentioned before, even for people that are not diagnosed with PTSD, but who have mental health related issues, service dogs can be great. Additionally, other types of animals can be just as therapeutic, as we are continuing to learn about the benefits of animals with mental health. I personally have met people who struggled with trauma or their mental health, and had a service animal other than a dog. Although the animal may not be able to do certain tasks that a dog could, not everyone has the same opportunities to own a dog. Therefore, other (smaller) animals are still helpful in providing that 24/7 comfort to someone who struggles with their mental health and may need in order to function throughout their day.

References:

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 4: Pathways to Recovery: Understanding Approaches to Trauma Treatment. Blackboard

By: Cameron Kunkle