It is interesting to start with the idea that Denny put forward in his article, Radio Builds Democracy, through which he talked about how radio bridged people to conduct public education by providing different points of view (Denny, 1941). The dimension of the network, back then, was closely knitted and expanded with the growth of broadcasting and the radio industry. The “social network” was somehow not too personal, but being discussed between the audiences and the educators. “You and Your Government,” a widely discussed program led by the National Advisory Council of Radio in Education in 1931, was an exemplary put to talk about how people relate to their public life and society. The followed forum discussion bring audience participation in 1935 and consequently enabled the possibility of forming casual relationships. In short, broadcasting elicited the emergence of various kind of discussion groups, clusters of opinion leaders, hence the growth of social networks.

If scrolling down our Facebook page or other social media accounts, it is not so difficult to decipher the composition of our “sparsely knit” personal communities. Friends, relatives, neighbors, and workmates constitute most part of our personal network (Rainie & Wellman, 2012). It is studied that Americans have only an average of 2.1 close ties in their outspread network. The Oxford anthropologist Robin Dunbar also pinpointed due to the limitation of people’s “social brain,” the series of layers of embedded relationships set the peak value to 150 (Rainie & Wellman, 2012).

The widely circulated theory and frequently applied number indeed explained people’s limitation of building connections and sustain relationships. The Yale sociologist and physician Nicholas A. Christakis also argue that “we and others have done a bunch of work to show that if your real friends online say or do something, it affects you. But if your online acquaintances online say or do something, it does not. People, on average, have about 106 Facebook friends, but only five or six real friends.”

The discussion of the social network size is mostly conducted around the comparison between strong versus week ties, quality and quantity aspects of relationships. Not only Dunbar but also many other researchers mentioned the limitation of people’s cognitive information-processing capacity, Oulasvirta et al. brought the theory of Resource Competition Framework (RCF) in explaining the “context-triggered” cognitive limitations. Obviously, bigger network asks for greater attention and efforts, but that does not necessarily mean the “week ties” are meaningless. As Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg once said, “think about what people are doing on Facebook today. They’re keeping up with their friends and family, but they’re also building an image and identity for themselves, which in a sense is their brand. They’re connecting with the audience that they want to connect to. It’s almost a disadvantage if you’re not on it now.” Networks, of course, have connected people to a considerable amount of week ties, but that innate with possibilities of higher capacity to make use of when necessary.

Here, we look back on Denny’s idea of how radio leads to democracy, the theory “division of labor in society” that raised by sociologist Émile Durkheim could be adequately applied. The ties valid by the radio connect different social networks, connecting every dots to build an integrated society upon various social environments, lead to a stronger bonding overall (Rainie & Wellman, 2012). The more ties people possess, the higher the possibility they will have to reach a more extensive network. Consequently, a closer and tighter knitted human society will be made.

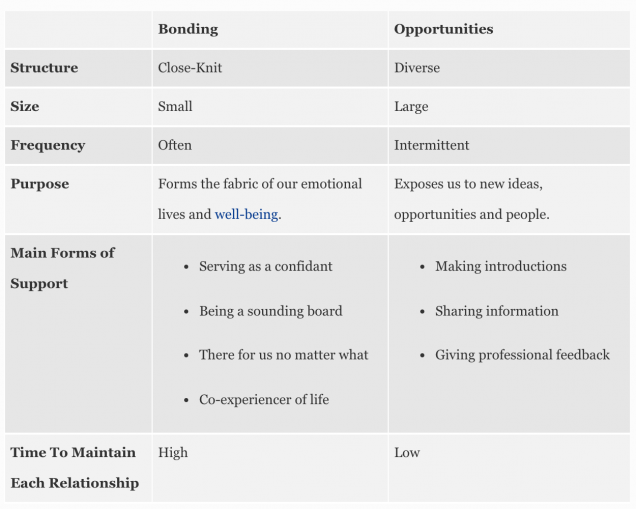

As what has been mentioned, it is not necessarily essential to choose from a closely-knit or widely developed network. Why can’t we have both? The small size of our close relationship serves special needs, and the specific personal communities cater to various scenarios. There could be more than one cores that do matter to people. Michael Simons also drew a table to summarize how the two aforementioned social networks serve our needs.

Besides, I would like to bring the chicken-and-egg discussion of whether there exists a causal relationship between social networks and neocortical growth. A study conducted by Jérôme Sallet and Matthew Rushworth of the University of Oxford in England in 2011 revealed a linear relationship between the size of a monkey’s social network and a growing of the neocortical grey matter relates to social cognition (Eric Johnson, 2011). They also had reverse experimented how individual variation in brain anatomy contributed to one’s success within the social group. The result in primates was positive.

Researchers from the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London carried the investigation into the specific realm of online social networking in 2011. They tested if the social behavior of social media users, mainly Facebook, relates to particular neocortical matters. The experiment has shown that the volume of an area called the “amygdala,” associate with the scale of one’s Facebook friends. Though there was no strong determination was made out of the research, Johnson suggested possibilities that online technologies facilitated people to expand social network and probably pushed the neocortical growth. If so, people who manage a sizable social network might potentially activate the part of their underutilized neocortical matter. Simply put, the more you social, the clever you will probably be.

Reference:

Denny, George. (1941). Radio Builds Democracy. Journal of Educational Sociology, Vol. 14, 370-377.

Rainie, Lee., Wellman, Barry. (2012). Networked: The New Social Operating System. The MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Oulasvirta, A., Tamminen, S., Roto, V., & Kuorelahti, J. (2005). Interaction in 4-second bursts: The fragmented nature of attentional resources in mobile HCI. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems (pp. 919-928). ACM.

Simmons, Michael. (2014). How Big Should Your Network Be?

https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelsimmons/2014/01/02/how-big-should-your-network-be/#769c062c3ddc

Johnson, Eric Michael. (2011). Social Networks Matter: Friends Increase the Size of Your Brain.

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/primate-diaries/social-networks-matter/