From Connectivity to Collectivity – Is Facebook a Fertile Ground for Social Movements?

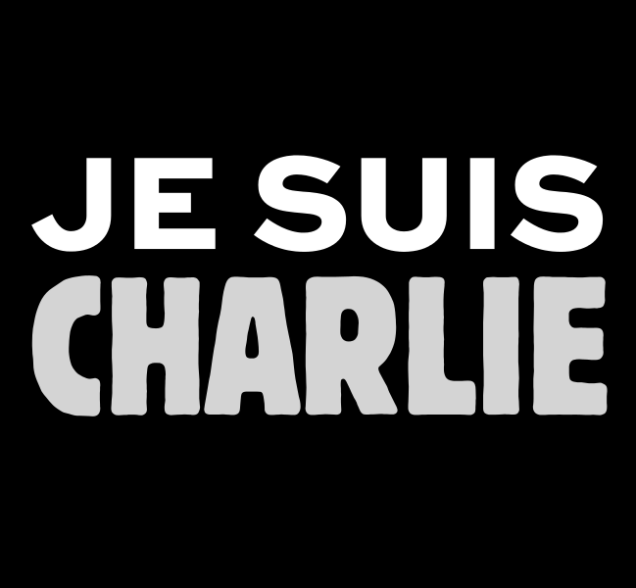

Thinking back to all the Facebook profile pictures you have ever used, did you change your profile picture to the image of the slogan “Je suis Charlie” (“I am Charlie” in French) after the 7 January 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting to show your empathy for those writers and editors attacked and to embrace freedom of expression? Or did you in contrast choose to put “I am not Charlie” on your profile picture to oppose the offensive humor in the Charlie Hebdo magazine? Did you “French national flagged” your profile picture after the bomb blasts and shootings in the P aris attack on the night of 13 November, 2015? Later in 2016, did you then change your profile filter to a rainbow flag to honor the victims of the Orlando gay nightclub shooting on June 12 or to show your support for LGBT community during the Pride week?

The solidarity filters have gain popularity among Facebook users since Facebook started to show compassionate gestures for the Paris attack in November 2015 but have also received criticism with people questioning why Facebook never promote national flag filters for crises in the third-world countries such as Lebanon and Syria. Facebook allows everyone to express themselves, which partly aligns with Hauben’s (1998) utopian description of democracy but still contains too much noise. When people have gradually gotten used to the civic engagement in form of changing Facebook profile pictures, adding sad and angry emoticons to news posts on terrorist attacks, or participating in street protests by commenting under its live video streaming, it brings the old “slacktivism or activism” question to debate.

How does online political participation contribute to the social movements? Breuer and Groshek (2014) measured how citizens’ online behavior is associated with their offline engagement in the Ficha Limpa campaign and found that the use of social networking sites in the promotion stage of the campaign lowered the cost and increased the efficiency of the mobilization. In addition, the decentralized nature and horizontalism of social networking sites such as Facebook enables the self-organization of social movements on Facebook without a formal organizer (Tufekci, 2017). According to Barberá et al (2015), the low commitment participants who are often considered as slacktivists actually acts as the critical periphery that is essential to help spread the word and raise awareness for social movements. Besides being a tool for a social movement campaign to reach a larger number of audience and diffuse information quickly within a huge peer to peer network, Facebook also breaks the information barrier between nation borders and helps brings the scale of influence and attention to a global level, which is the case of the role of Facebook in Hong Kong Umbrella Movement in 2014.

As powerful as Facebook can be in the mobilization of social movements, is it also an effective tool for persuading people with different opinions to change opinions and join the movement? This goal is probably a lot more difficult to achieve. When Facebook was launched in 2004, when Facebook was still called “Thefacebook”, it was designed as a place for users to disclose and update their personal information as well as connect with friends whereas now Facebook also functions as a public sphere where heated discussion about social issues take place. Among the initial features of Facebook, there was not a news feed feature to provide users with political and cultural digest from various sources. While Facebook has always insisted that its mission is promoting global connectivity, it is forming echo chambers and filter bubbles that prevent users from hearing different voices on the same issue from people who hold opposite opinions. The algorithms of Facebook personalize users’ news feed and expose users to targeted advertisements based on the analytics of users’ personal data collected both on Facebook and from external channels. With the polarization of views on issues especially political views, Facebook may not be the perfect tool for convincing people into abandoning their current opinion and adopting a new opinion.

Networked wearable technologies in the near future will certainly enhance the mobility of social networking platforms such as Facebook. Thinking from the internet of things aspect, will future social movements and protests utilize the internet of things to solve difficulties in transportation and to come up new ways to confront regulation forces of the government? In the era of online-mobile networks and potentially the coming future of ubiquitous computing, will the new generations of the growing geek culture with increasingly sophisticated hacking skills be the new impeccable weapon of future social movements?

By Minkuan Chen, BU Emerging Media Studies Master’s Student

References:

Barberá P, Wang N, Bonneau R, Jost JT, Nagler J, Tucker J, et al. (2015) The Critical Periphery in the Growth of Social Protests. PLoS ONE10(11): e0143611. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143611

Breuer, A. and Groshek, J. (2014). “Slacktivism or Efficiency-Increased Activism? Online Political Participation and the Brazilian Ficha Limpa Anti-Corruption Campaign.” In Y. Welp and A. Breuer (Eds.), Digital Opportunities for Democratic Governance in Latin America (pp. 165-182). Routledge.

Hauben, M., & Hauben, R. (1998). The Net and Netizens: The Impact of the Net on Peoples Lives (Chapter 1). First Monday, 3(7). doi:10.5210/fm.v3i7.607

Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. S.l.: Yale University Press.