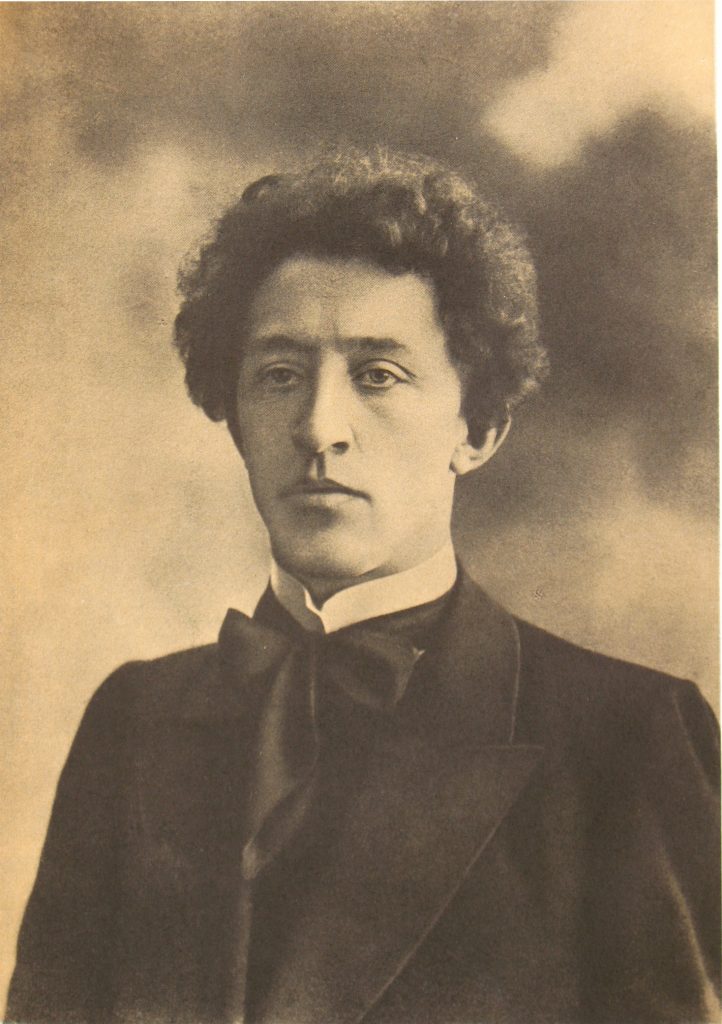

Biography Aleksandr Blok

Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Blok (1880-1921) was a leading figure in the Russian Symbolism, and had a huge influence on Russian poetry. He was born in 1880 into a family of a law professor of Warsaw University and a talented writer and translator. His parents separated soon after his birth; and he spent his childhood in the family of his maternal grandfather A.N Beketov, a botanist and Rector of Petersburg University, in Petersburg and Shakhmatovo, near Moscow.

Blok was educated at the Vvedenskaya Gymnasium in St. Petersburg, and then entered the Law Faculty of St. Petersburg University, before transferring to the History and Philosophy Department, where he completed his studies of Slavic and Russian languages.

He began writing poetry at age 17, and in 1903, some of his poems were published in D. S. Merezhkovsky’s magazine, the New Way. In 1903, Blok married a daughter of the famous chemist D. I. Mendeleev Lyubov Mendeleyeva, who would go on to become a professional actress and a historian of Russian ballet. By 1906, when he graduated from the university, Blok was a recognized author of Verses on a Beautiful Lady (1904). The collection of poems devoted to his wife reflected on the Beautiful Lady as incarnation of the Divine and the Eternal Feminine. Later Blok wrote several plays, including the lyric drama The Fairground Booth (1905-1906) with stock characters and forms of expression from the Italian Commedia Dell Arte, and The Rose and the Cross (1913), which was based on medieval French romances. Blok’s dramas were highly regarded for their literary value and responsiveness to history and to current social situation. It is believed that The Fairground Booth voiced the moods of loneliness and pessimism of the Russian intelligentsia in the aftermath of 1905. Blok’s second collection of poetry, Inadvertent Joy (1907) marked his spiritual crisis.

In his mature poetry, Blok concentrated primarily on political themes, pondering the messianic destiny of Russia and returned to classical models (the unfinished verse epic Retribution, 1910-21; My Country, 1907-16). In verses Russia and On Kulikovo Field (both 1908), the image of Russia rooted in its religious past, and searched for a way to the present.

From 1909 to 1916, despite his feelings of personal failure, Blok wrote poetry of high artistic achievement. The Terrible World, In the Restaurant, Night Hours, and Dances of Death are particularly indicative of his spiritual turmoil and difficult marital relationship. In 1909, during a temporary reconciliation, Blok and his wife traveled in Italy. This trip resulted in the Blok’s exquisite collection cycle Italian Poems (1909). The events of the same year — a journey to Warsaw at his father’s funeral and his 9-month-old son’s death made Blok to turn to the new themes — his aristocratic lineage and his relationship to Russia’s literary and cultural past, in particular, to the work of Aleksandr Pushkin. These themes are reflected in his semi-autobiographical unfinished epic poem, Retribution (1910-1921), which he began to write shortly after his father’s death.

In 1916, Blok was conscripted into the army and served behind the front lines in civil defense work near Pinsk. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he advocated the October Revolution, though less for its promise of social and political reforms, than for “the music of the Revolution” (Blok). Spurning a chance to emigrate, Blok worked for the Bolshevik government for a while. In 1917-18, he served as as stenographer during interrogations of Tsarist ministers, whose findings he later published under the title The Last Days of Imperial Power.

His last great poetic work, The Twelve (1918), was a complex allegory that cast twelve Red soldiers on the streets of Petrograd as the twelve apostles. Highly ironic and polyphonic poem employs colloquial talk, slang and language of slogans. Only much later, this experimental work was recognized as one of the first great poems of the literature of the 1920s. Almost simultaneously with The Twelve, Blok wrote The Scythians in which he expressed his views on Russia as a mediator between Europe and Asia.

Under the Soviet regime, Blok was a translator for The World Literature Publishing House, served as a member of the directorate of the state theaters and a chairman for the Petrograd section of the All-Russian Union of Poets. In 1919, he was briefly arrested and interrogated by the Petrograd Cheka. Blok’s heavy workload for various state institutions and his increasing disillusion with the Revolution left him spiritually and physically exhausted. He suffered from asthma and heart trouble, as well as chronic depression that prevented him from writing. By 1921, Blok did not write any poetry for three years. In one of his last published works, The Decline of Humanism (1921), he lamented the dissipation of European style and the loss of heroes who could persuade men to act rationally in true self-interest.

In 1921, Blok sought an exit visa to get medical treatment abroad, but his requests were denied until it was too late. He died on 7 August 1921 in Petrograd.

Sources

Berberova, Nina Nikolaevna, Aleksandr Blok: a life, New York: George Braziller, 1996.

Franklin D. Reeve, Alexander Blok: Between Image and Idea. Columbia University Press, 1962.