Manove’s Dissertation Advice for PhD Students

In my first year at college, I was assigned an adviser from the physics department. He was a senior professor, not too many years from retirement. “You can ask me anything you want,” he said in our first meeting, “but don’t ask me about sex—I don’t remember it.” I finished my own thesis more than 50 years ago, so perhaps I ought to adopt a similar attitude about dissertations. Instead, I will bother you with unsolicited advice. My advice is completely unofficial: it does NOT represent department policy in any way.

When to Get Started

“Anyone can write a good dissertation,” they say, “but not everyone can finish it quickly.” Yes, but it helps if you get an early start. If you want, you can sit around thinking, “I don’t have any ideas,” “I’m embarrassed to talk with a professor,” or “I have to put all of my energy into being a TA.” Those feelings are natural, but it’s in your self-interest to ignore them. Some students say to themselves, “Now that I’ve finished my coursework, I’ll relax for a year.” Sure, you deserve a rest, but the opportunity cost of a long rest is certain to be very high. In my view, you should start working on your thesis as soon as your second-year paper is finished and you have no more than one course left to complete. Normally, this means that you should start working on your dissertation by the end of the first semester of your third year, or sooner.

Choosing a Topic

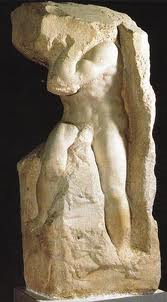

Michelangelo wrote: “Every block of stone has a statue inside it, and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.” Likewise, after years of coursework, after reading the newspapers, after listening to professors, preachers and politicians, you have a good idea for a dissertation topic somewhere inside your brain. You have only to find it. And a topic that you discover yourself is bound to be more motivating than one suggested by an adviser would be. Almost everything that goes on in this world, from sinning to soccer, has an economic aspect that can be explored. Inasmuch as pure theory and econometric theory aren’t exactly about what goes on in the world, the discussion below is probably less applicable to those fields.

Unless you are a true genius, a good thesis topic is a narrow topic, not one designed to revamp a field of economics. But narrow topics can help answer broad questions. For example, think about the topic “What Does Schooling Do?” A lot of work has been done in this area, but there’s a lot more to find out. Do students learn productive skills in their coursework? Or do they merely learn self-discipline and how to meet deadlines? Does schooling yield positive externalities to others in the community? Do people attend college as a signal of their ability? Or is college primarily a consumption activity? There’s room for a thousand new papers here alone.

To me, the most important question in development economics is “Why are poor countries poor?” There must be a large number of partial answers to that question. Can you find one of them? Or why did China get rich so fast? If you’ve lived in China, you may have a small idea that you can develop in this area.

Of course, if you like the idea in your second-year paper, you may want to continue to work on that topic. If you’re bored with it, choose something else. It’s hard to work when you are bored.

The department has many research seminars and workshops, some say too many. Check them out at http://www.bu.edu/econ/econcal/. Start attending them in your second year, and by your third year, try to attend at least two a week. In many of the workshops, PhD students are presenting their research. These are great places to see what others are doing and to help you find ideas for your own research. In recent years, PhD students have established a number of reading groups in which students present the work of established scholars or preliminary versions of their own work. Most PhD students find the reading groups to be very useful as well.

Keep in mind that “the best is an enemy of the good.” You don’t need a formal search model to know that it doesn’t make sense to search until you find the perfect topic. Start working on something quickly; you’ll have plenty of time to shift the topic as you go. After you find an idea of interest, write up a description of the idea in a few pages of prose—no math or econometrics allowed. Then go off to talk with faculty members. [Caution: some pure economic and econometric theorists dislike the verbal approach, but I myself believe in it.]

Finding Dissertation Advisers

All faculty members are busy. Some are busy working, and some are busy feeling guilty about not working enough. But that’s their problem, not yours. Your problem is to find several faculty members (normally three), busy or not, who can advise you on your dissertation. When you want to meet with a faculty member, send an email asking for an appointment. If she doesn’t answer within a day or two, just resend the email (no need to write another one). If the faculty member says, “I don’t have much time this week,” you can respond, “When will you have time?” Eventually, you will have an appointment.

Begin discussing your ideas with faculty as soon as you have written a few pages describing one or more of your ideas. This should happen by the end of the first semester of your third year. Talking with a person of the opposite sex (or the same sex if you prefer) doesn’t require you to marry him or her. Likewise, talking with a faculty member about a research idea, doesn’t require you to adopt her as an adviser. That can come later, after you have been meeting with the person on a regular basis. Meet with several faculty members. If you are working on health economics, for example, you may want to meet with someone who is knowledgeable about the institutions in your favorite country, someone else who knows theory, and someone else who has experience with empirical work and data (yuk). If you enter a faculty member’s office, and find it too messy or too clean, or if his shirt is the wrong shade of pink, then try someone else. Shop around.

Some faculty members already have a large number of advisees, and some, especially the younger set, may have very few. You can find out how many by asking around or by asking Andy Campolieto, who tends to know these things. As with most choices, there’s a tradeoff here. Having lots of advisees is a good signal about advising quality, but it may be a bad signal about available time. Younger faculty with few advisees may be able to give you more time, may have lots of fresh ideas, and may have very up-to-date knowledge of technical tools. Take a look at their CVs to see what they are publishing. And don’t forget that if you want to be a professor when you grow up, you might look for a primary adviser (first reader) who has lots of contacts and can help you get a good academic job.

Try to see your advisers on a regular basis, at least every week or two. The main reason for doing this is not to hear their penetrating comments, but rather to keep yourself working. It’s embarrassing to return to a professor’s office and say, “I haven’t done any research in the last two weeks.” You will have a strong incentive to work hard and avoid embarrassment, which is the most painful and best remembered of all emotions.

If you plan to write an empirical thesis, and most of you should, you will need data. The most important thing you need to know about data is that the word “data” is plural. If you accidentally say “this data” instead of “these data” you won’t sound like the pompous scholar that you want to be. The next most important thing to know about data is what data to get and how to get them. Good advisers can be especially helpful for this, though some of you may have special knowledge or connections with institutions in your home country that will permit you to acquire data on your own. In any event, you should start working on data acquisition as early as possible, because the process can be slow and sometimes costly. You may also have to clean the data before you use them, an activity that requires both the innocence of youth and the guiding hand of an adviser who wouldn’t want to do it herself.

The Dissertation Proposal

In recent years the dissertation proposal has become optional, but I strongly recommend it. Bart Lipman stated that the proposal “needs to be specific enough that your advisors [he means “advisers”] can say with a reasonable degree of confidence that at least most of what you propose to do can be done and is worth doing.” I would say it this way: the plan of research described in your proposal should be feasible and sufficient to qualify you for the degree. I recommend that you include a detailed table of contents in the proposal, and next to each item write “completed” if it has been completed or the date by which you plan to complete it. If your committee accepts your proposal, it serves not only as a research plan, but also as an informal contract that sets out what you are expected to do in the final dissertation. If you do what you say you will in the accepted proposal, your advisers are less likely to insist on more work later.

Some time ago, the GIC decided to impose a deadline for the proposal at the end of May of your fourth year. That deadline was far too late. If you begin working on your dissertation in the first semester of your third year, as you should, then May of your fourth year will seem very far away. You may be seduced into spending all your time teaching, talking with your mom on the phone, or worrying about your kids, none of which are productive activities. Find a commitment device that requires you to defend your proposal during the first semester of your fourth year. For example, you could give $1000 to Albert Ma, and tell him that he can keep $20 for each day that you are late.

The Job-Market Paper

If you want to obtain a good research-oriented job, you will need to complete a potentially publishable job-market paper by the end of October in the year you go on the market, normally in your 6th year nowadays. The October deadline is not a flexible one: every day that goes by after that deadline lowers your expected number of interviews at the Meetings. Without interviews you won’t have fly-outs, and no fly-outs, no-job. Yes, there are exceptions, and the Catholic Church recognizes miracles, but these are rare.

The job-market paper is usually a completed chapter of the doctoral dissertation. If you defend your proposal at the end of May, you will have five months to complete the paper, which isn’t a lot of time to get your first publishable paper ready. That’s another reason why I recommend an earlier December deadline for the proposal.

I’ve started to read many job-market papers, and I’ve read a few of them completely. The most important thing about a job-market paper (or any research paper) is the title. A good title is informative, though probably not cute. If the title sounds uninteresting, a potential reader is likely to move on to the title of someone else’s paper. Next comes the abstract. The abstract should explain in a few words what you have done and why it’s important or even surprising. If the abstract is dull or incomprehensible, the reader is likely to assume that the rest of the paper is the same way and place it gently into the recycle bin. (This is a bad thing, because recycled paper lowers the demand for wood pulp and reduces the incentive to grow trees.) Next in importance comes the introduction. Here you not only explain what you’ve done and why it’s important, but you also explain the intuition behind your idea in words. Provide examples wherever possible. If after reading the introduction, I don’t understand what the author is doing, I assume (correctly) that the author doesn’t understand what he is doing either, and I go no further.

As for the rest of the paper, you want to continue to emphasize intuition and examples. Put most of the nasty math and proofs of propositions in the appendix. Some economists think that lots of technical stuff will impress others in the profession. But the truth is that too much math interrupts the flow of your argument. In fact, very few economists like to read math, and those who do are likely to be rather strange—just think about my colleagues in theory. Be sure to finish your paper on time, be sure that your advisers read the paper and quiz you about it, and have it copyedited before you send it out.

The Doctoral Dissertation

The normal dissertation consists of three papers, related or otherwise. Two of the papers should be pretty good, and potentially publishable; the third paper can be a kind of filler so long as it doesn’t embarrass you or the department. The entire dissertation has a title and an abstract, which the dean reads (make sure it’s grammatical), and, normally, an introduction and conclusion. The thesis as a package isn’t very important nowadays—nobody but your mother or father is likely to pay any attention to it. It’s the papers inside the thesis that are of interest: you will put them online and eventually submit them for publication.

The Dissertation Defense

Before you can graduate with your PhD, you must describe your dissertation in a so-called dissertation defense. At BU (and in most US universities) the defense is an informal formality that takes place when the dissertation is substantially complete. You will have about an hour to review your work and answer questions from the examining committee. After that, the examining committee meets and decides whether or not you passed the defense (almost everyone does) and then decides whether or not a bit more work is necessary (it usually is).

The examining committee consists of five people: your three advisers and two other faculty members who serve as warm bodies. Your advisers are expected to read and comment on various versions of your thesis in advance of the defense; the warm bodies (fourth reader and chair of the examining committee) are expected to attend the defense and ask a question or two during your presentation. With the agreement of the DGI, you may be able to choose the warm bodies yourself, but be careful: they must be intelligent enough to write their initials on the required form and to sip the cheap champagne-like fluid they serve after they tell you that you’ve passed. I myself often serve as a warm body, and I enjoy the process.

Conclusion

The main ingredients for success in a PhD program are self-confidence, self-discipline and ambition. Intelligence has little to do with the process. I’m confident that I’ve given you good advice, even though some of my colleagues will undoubtedly think it’s disastrous. Fortunately, by the time you find out and decide to hold me responsible, I probably will have retired and gone off to enjoy the sunshine in Tenerife or some such place. This is odd, because I don’t like sunshine.