Cookbooks & History: Lemon Faludhaj

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to bring in to class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the final essay in this series, written by Salma Serry.

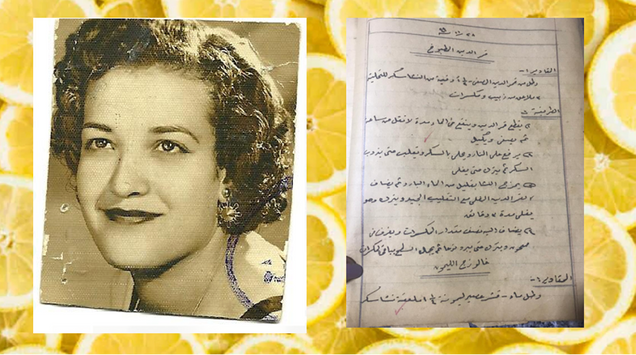

She was always the first one to wake up in the house. I would get up around 7’oclock in the morning -despite it being the summer holiday- and I would find teita Samira (teita: grandma) sitting in her bright little sewing room singing along with her little portable radio. She had a beautiful voice and she loved singing while doing chores in the house. After flipping through some German Burda fashion magazine for patterns or rummaging through her cookie-tin that turned into a sewing box, she would head to the kitchen to make breakfast and start with her lunch preparations. The kitchen was her empire. That was where she would spend hours tirelessly putting together wonderful creations for every day meals, big weekend family lunches and glorious birthday table spreads, the likes of which were- and still are- hard to find in bakery shops.

A few weeks ago, I called my mother in Dubai to ask her about some cookbooks that teita had given to my aunt before she passed away, and to my surprise, she remembered recently finding an old notebook which teita had given her when she first got married, about thirty years ago. She wrote the notebook herself when she was just about twelve years old in 1949 in school as part of her home economics subject. It was fascinating to know of its existence, having spent years searching around Cairo for old recipe collections and begging owners to let me take a look at them or borrow them for my research. Little did I know, I had one by my very own grandmother lying around in the house I grew up in.

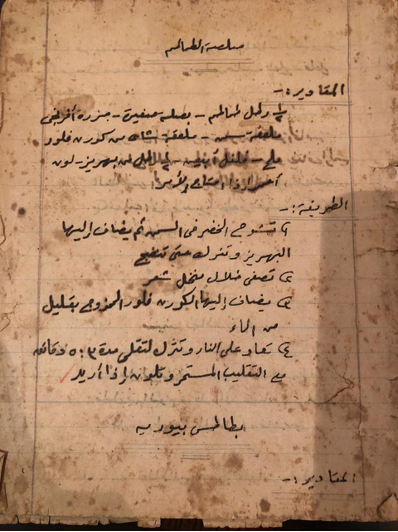

Forty-seven recipes. Every recipe is dated. Her handwriting is so neat and meticulous, one would never guess it’s by a twelve-year-old. Unfortunately, the notebook has lost its cover, so the first and last pages are barely hanging in place, with many tears and a lot of little splatter-stains that have turned a homogenous brown over the years. The insides are intact and in good condition. Almost all recipes are marked with a red check and, in some places, they read “well-done” and “your efforts are appreciated.” I suppose these comments must have been written by her teacher.

As I flipped through the delicate pages and the recipes that vary from French Baton Salé (localized with a sprinkle of cumin seeds) to traditional Eid Kah’k cookies, I stopped at a rather peculiar recipe title: Lemon Faludhaj (Faludhaj: starch-based pudding). You see, I have never seen it any of the modern or contemporary cookbooks of Egypt nor have I heard any Egyptian speak of it. My own limited knowledge of it is from two sources, each a thousand years apart from the other. The first is my experience having grown up in Dubai where Indian-style cafeterias sell a street dessert named Faloodeh/Falooda made up of thin starch noodles swimming in a semi-frozen syrup- and sometimes icecream- topped with fruits and nuts. I later came to know that it is widely popular in Iran, India, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. But my knowledge of it remained limited within these geographies until I found it in a 10th century medieval cookbook from Baghdad!

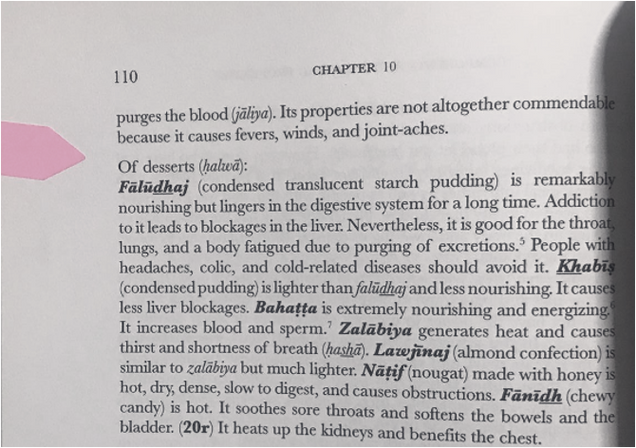

In fact, the 900-something-page book, which today is translated into English by Nawal Nasrallah, features an entire chapter dedicated to only faludhajs: Faludhaj for the Caliphs, Faludhaj for the Princes, Chewy Faludhaj, Thick Faludhaj and the list goes on. In her notes, Nasrallah explains how, etymologically, the word is derived from the Persian paluda, which means among other things “strained,” translucent, and of a jelly-like consistency. She notes that the chewy type of faludhaj is very close to today’s “Turkish delight” which we call in Arabic Rahat Al Hulkum (Arabic for throat’s comfort), and which I believe has been translated into Turkish to to “lokum” (note the phonetic similarities between hulkum, meaning throat in Arabic and Turkish name for the dessert,“lokum”).

The same book generously provides medicinal advice and food characteristics based on the humoral system (see Galen’s humoral theory). According to the book, Faludhaj has characteristics that are especially “good for the throat,” lungs, and fatigued bodies. And interestingly, my aunt tells me that teita used to make faludhaj whenever any of her children had a sore throat. She distinctly recalls a time when she was about 8 years old and had her tonsils removed when teita made her some in strawberry flavor. How can a piece of knowledge travel through a thousand years? And perhaps more interesting, how does it die out within two generations (between my grandmother and my rather clueless self) in a span of 50 years after having survived more than a thousand years? Almost no one I know in Egypt recognizes the recipe anymore.

In any case, I went ahead to try out teita’s recipe below which was incredibly quick to prepare with minimal ingredients, but for some reason it did not specify whether a tablespoon or teaspoon is needed for the amount of cornstarch. The unit used for measuring water is a pound (that was before Egypt changed to metric system later in the 70s)- which equates to almost two cups of water. I started out with one teaspoon and ended up having to use 4.5 tablespoons to get to a thick pudding consistency. Maybe they had a stronger type of cornstarch? In comparison to the 10th-century recipe, the starch used is wheat-based, it calls for sesame oil as well as honey instead of sugar in addition to infusing saffron for coloring and perfuming.

Lemon Faludhaj

Ingredients:

2 cups of water

Juice of 1 lemon and its zest

1.25 spoon of cornstarch (I ended up having to use 4.5 tbsp)

Sugar (recipe doesn’t specify amount but I used 5 tbsp)

Instructions:

Melt cornstarch in cold water.

Rub the sugar into the lemon juice.

Add the sugar and lemon juice mix into the water along with the zest and bring to a gentle simmer.

Add the cornstarch mix and stir well continuously under low heat until the starch is cooked.

Pour into bowls and garnish with nuts if desired.

After leaving it to sit overnight in the fridge, I tried it the next day and it had a good pudding consistency. It was really rather refreshing – good to pair after heavy dinners perhaps or as a summer snack. If I were to make a few tweaks, I would only use half the amount of zest as it was a little overpowering and slightly bitter, and I would also experiment with it again replacing sugar with honey and adding a little sesame oil or some fat as the medieval recipe calls for – something a colleague also pointed out that could enhance the thickening process (thank you Sarit!).

All in all, it was a fascinating experience. A reliving of the past. A reenactment of imagined histories. It made me think of my grandmother as a little girl in school perhaps learning to cook with starch for the first time. It made me think of my aunt finding cooling comfort in its soft and gentle texture after her tonsil operation, a medieval maid preparing it for a sick little prince, and an Abbasid caliph enjoying its saffron-perfumed silkiness in his palace garden after a hearty lunch. All these people and places connected with this creation that carries a name of a dish with variations still popular in the Arab Gulf, India, Turkey, and Iran. And I have my late teita, Samira, to thank for extending this link to me.

Bibliography

Attia, Samira. 1948-1949. Personal Home Economics School Notebook. Cairo.

Works cited

Ibn, Sayyār -W.-M. N, Nawal Nasrallah, Kaj Öhrnberg, and Saḥbān Murūwah. 2007. Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens: Ibn Sayyār Al-Warrāq’s Tenth-Century Baghdadi Cookbook. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill NV.