Cream Candy from La Cuisine Creole

This guest post is part of a continuing series written by students from Karen Metheny’s Cookbooks and History course. Kate Watson documents her recreation of a recipe for 19th century cream candy.

I’ve never tried to follow a pre-1900 recipe before, but for my Cookbooks and History class in the BU Gastronomy program, I chose to recreate a recipe for Cream Candy featured in La Cuisine Creole, an 1885 collection of New Orleans recipes collected by Lafcadio Hearn.

Although it was very hard to decide on just one recipe to recreate, I settled on this Creole recipe for Cream Candy. I chose this because I enjoy candy making— I’ve been gifting my special English Toffee to family and friends every year at Christmas for the past decade, and I enjoy experimenting with new candy types. I also love creamy flavored candies, so I imagined that this recipe would fit the bill.

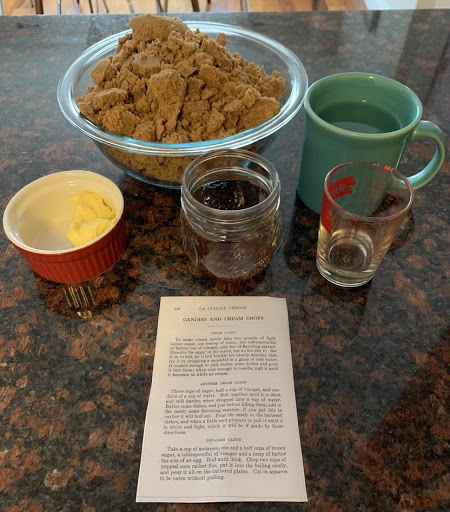

I assembled my ingredients. Luckily, the measurements were relatively standardized:

2 pounds light brown sugar (I actually used dark brown)

1 “teacup” of water (I used a mug- when I measured, it was ~1 cup)

2 “tablespoonfuls” of butter (I used salted Kerrygold)

1 tablespoon vinegar (I used plain distilled white vinegar)

2 tablespoons flavoring extract (I used Nielsen Massey Bourbon Vanilla Extract)

I added all the ingredients to my enameled cast iron pot and turned on the heat. Adding everything at once felt strange, as I would usually add vanilla last, but maybe that’s why there’s so much extract?

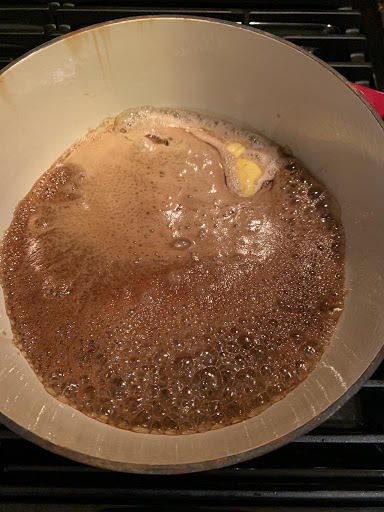

The recipe specifically said not to stir, so I knew I was working with a traditional caramel (something I’d never made before- I’ve always “cheated’ and used recipes that call for a bit of corn syrup). I decided to use a technique to prevent crystallization, even though it wasn’t specifically mentioned in the recipe: a brush to wash down the sides of the pot as the caramel cooked. It was really hard not to stir the ingredients! I was nervous about something burning as it was so dark.

When it came to a boil, I set the timer for 20 minutes and readied a jar of ice water, to test the doneness of the candy.

After 20 minutes, my house was filled with the rich smell of vanilla, butter, and cooking brown sugar.

At this point, it was at very soft ball stage. The recipe said that it would be ready when the candy is “cooked enough to pull” but I didn’t really know when that would be. I decided to cook it for a couple more minutes. I usually judge “doneness” of a caramel by color, but since this recipe used brown sugar, it was already so dark that it was impossible for me to judge. At about 22 minutes it had reached medium-hard ball stage, and I decided it was ready.

I poured the candy out onto a buttered rimmed baking pan. It was quite beautifully colored and smelled rich and delicious.

It was also scalding hot!

It quickly developed a skin, and after around 5 minutes had cooled enough for me to move it around with my finger.

I took a small piece off the edge and began to experiment.

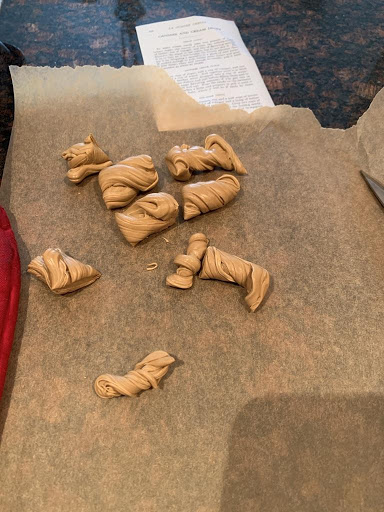

The candy began to lighten as I pulled. It was actually pretty hard to pull- my hands and arms were tired after a little while. It was very hot at first, but cooled after around 5 minutes of pulling, and the strands started to break. I decided to twist it and cut it into pieces with kitchen shears. It never became light as cream, but it did reach a nice café au lait color.

I still had the rest of the rapidly cooling candy to pull- it would definitely have been easier with a houseful of children to help me! I decided to pull the rest of the candy, all at once, before it cooled too much to work with.

Although it was difficult, it was also pleasurably tactile to pull the warm candy. The repetitive motion reminded me of the repetition of kneading bread. As I pulled, the strands became beautifully pearlescent. The colors progressed from the very dark brown of cooked sugar to a rich mahogany color and looked almost like wood grain as I continued to pull.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t fully pull all of the candy before it cooled to the point where strands began to snap, but I had plenty for my family and classmates to sample. I snipped strands into small pieces and wrapped them in waxed paper for my class.

These candies, to me, did not taste like what I would expect a “cream candy” to taste, though they were delicious. They mostly tasted like the rich tangy flavor of caramelized brown sugar, with some smooth dairy mouthfeel from the butter. The vanilla was only slightly detectable, but it did add a slight aroma. I couldn’t taste the vinegar at all, and I’m not sure why it was part of the recipe, although I’m sure that acid was needed for some scientific reason.

The texture of these candies was unique and interesting. They were very hard when fully cooled- hard enough to shatter. However, when you put them into your mouth, they softened and became smooth and chewy (dangerous-to-dental-work level chewy, I wouldn’t give these to my grandmother without a warning!). The closest thing I’ve had before is the texture of a See’s candy lollipop- quite hard, so you can bite off a piece, but then also chewy inside your mouth.

If I were to make this recipe again, I’d try it with different types of sugar- both light brown and white. I would also try to take it off the heat at a softer ball stage, to see if that would change the texture. I would add the vanilla after it was taken off the heat, as I usually do, though probably not 2 full tablespoons of vanilla.

Creating a historical recipe made me appreciate the tremendous knowledge cooks of the time must have possessed. Although this recipe was “easy” and used few, simple ingredients, I did need to call upon my knowledge of candy making techniques to understand when it was ready. As I’d never made pulled candy, I was definitely guessing. I wasn’t able to fully process the candy before it cooled- it would have been much easier with a large family full of children to assist me with the pulling process!

Bibliography

Hearn, Lafcadio. 1885. La Cuisine Creole: A Collection of Culinary Recipes From Leading Chefs and Noted Creole Housewives, Who Have Made New Orleans Famous for its Cuisine. New Orleans: F.F. Hansell & Bro., Ltd. https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa/19#page/247/mode/2up

Accessed November 10, 2019