Projects

Temporal attention

The dynamics and limitations of visual attention across short time intervals (~1 s) shape perception and our ability to interact with the world. In this ongoing project, we combine psychophysics, MEG, and computational modeling to understand the continuous interaction of voluntary (goal-directed) and involuntary (stimulus-driven) temporal attention. We have found:

- Voluntary attention to a specific point in time leads to perceptual tradeoffs: performance is better at the attended time but worse at unattended times. This finding indicates perceptual limits over short time intervals that can be flexibly managed by attention.

- Our model of temporal attention explains behavioral data and predicts that attentional resources are limited across time.

- Attending to a moment in time changes neural activity both leading up to and following an attended time, revealing unique neural mechanisms for temporal attention that may be driven by the distinctive demands of temporal processing.

- Small eye movements called microsaccades decrease in anticipation of an attended stimulus. This stabilization of eye position with voluntary temporal attention may help us see brief stimuli.

- Despite differences in visual processing across space, voluntary temporal attention affects perception similarly across the visual field.

Attention and uncertainty in perceptual decision making

Visual information is always uncertain. Sometimes that uncertainty comes from the external world – for example, on a foggy night. In this project, we ask how people make perceptual decisions when uncertainty comes not from the external world, but from their own attentional state. We found that people’s perceptual decisions and confidence take into account attention-dependent uncertainty, in a statistically appropriate way.

Perceptual awareness

Our lab is part of two large “adversarial collaborations” to adjudicate theories of perceptual awareness. One project aims to distinguish first-order vs. higher order theories of consciousness, while another aims to test multiple higher-order theories.

As part of these projects, we have found that spatial attention strongly decouples subjective awareness and objective perceptual performance, giving rise to the phenomenon of “subjective inflation” across a wide range of stimulus and task conditions.

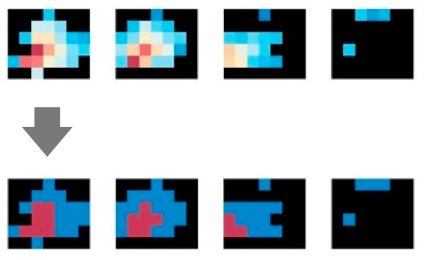

Pupil modeling

The pupil dilates not only when light levels increase, but also in response to many kinds of perceptual and cognitive events. But the dilation is sluggish, so if multiple events occur in quick succession, we must disentangle how each one affected the pupil. We developed and tested a pupil modeling framework to estimate how perceptual and cognitive events affect pupil dilation.

Code for our Pupil Response Estimation Toolbox (PRET) is avaiable on GitHub.

Human LGN M/P imaging

The lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) is the primary thalamic relay from the retina to the visual cortex. Its magnocellular (M) and parvocellular (P) subdivisions process complementary types of visual information, but they have been difficult to study in humans. We used 3T and 7T fMRI and specialized visual stimuli to functionally map the M and P subdivisions of the human LGN noninvasively for the first time.

Code for the M/P localizer is avaiable on GitHub.

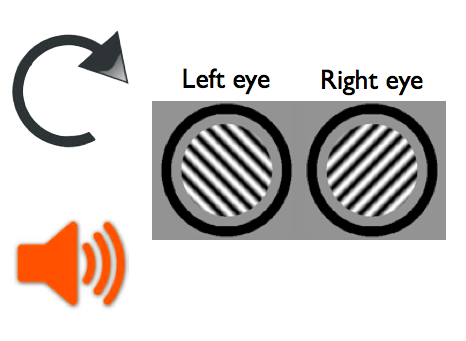

Prediction and perceptual selection

How do expectations affect what we see? We studied how predictive visual context, which contains information about what is likely to appear next, influences perceptual selection during binocular rivalry. Intriguingly, we found prediction effects (see what you expect to see) with a rotation sequence and newly learned audio-visual pairings, but surprise effects (see the unexpected) with newly learned natural image sequences. In this line of research, we try to understand when, how, and why perception prioritizes the expected vs. the surprising.

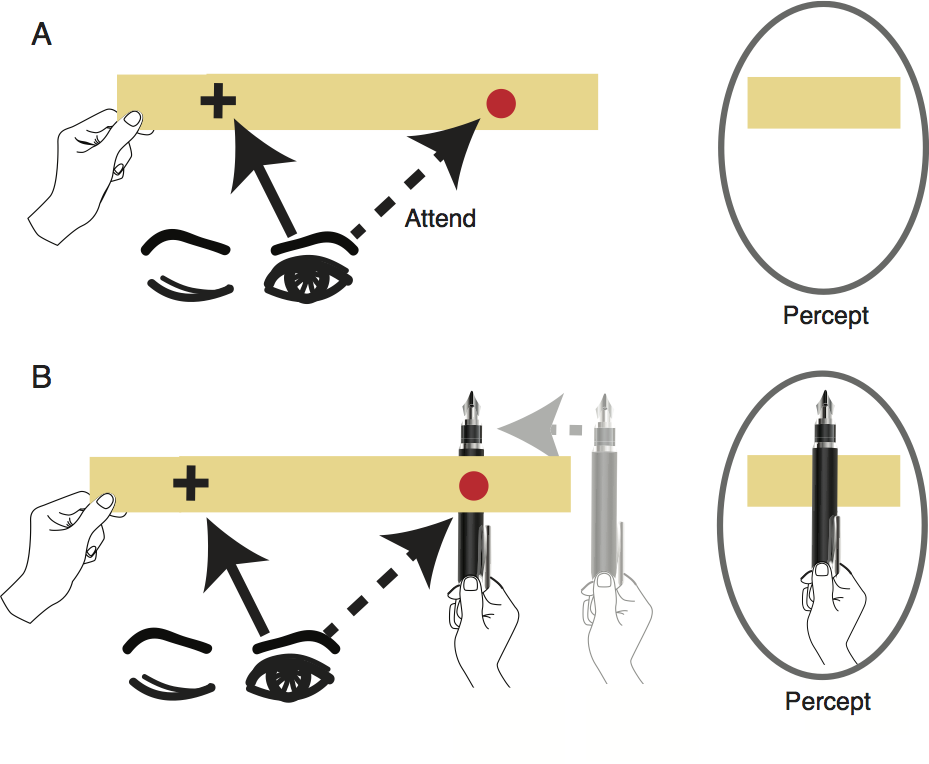

Perceptual selection of illusory content

We developed the Jumping Pen Illusion, which you can see for yourself with nothing more than a strip of paper and a pen. In the illusion, a pen held behind a strip of paper appears to jump in front of the strip! In lab experiments, this illusion helped us learn that classic dynamics of perceptual competition occur even between illusory percepts — here, percepts filled in across the retinal blind spot. Surprisingly, the filled-in percepts can affect depth perception of other objects in the scene that have unambiguous, disparity-defined depth.

Demo instructions! If you try it in your classroom, we’d love to hear.