Home

Volunteerism as Trauma Therapy

“The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.” – Gandhi

Trauma not only affects the brain, body and outlook, but also annihilates the perception of agency over one’s life. The abused child, the veteran struggling with memories of wartime horrors and the woman who dares not speak of what she experienced are often left feeling alone and impotent, vulnerable to the world’s ills. Mental health counseling is a time-honored technique for regaining a feeling of ownership over life, but supplements to these traditional therapies have been proven to help increase the efficacy of other methods and speed healing. When it comes to mental health, the more you give, the more you get.

Volunteerism is an alternative approach that researchers have discovered to be both personally empowering and socially productive. Studies have shown the practice to lower symptoms of PTSD, anxiety and depression while increasing life satisfaction and overall health. And frequency correlates with degree – the more hours, weeks and years devoted to service, the better the mental health outcome.

But why does an activity that focuses on others help the Self? Several theories have been floated about the power of volunteerism, but the correct one may be the sum of many, and personal accounts support that. Iraq war veteran Tim Smith credited his improved PTSD to being part of a team (Lett, 2018); Wisconsin Army National Guard veteran John Stuhlmacher appreciated his renewed sense of purpose and commitment to something “greater” than himself (Silver, 2019); meanwhile, Ricky Lawton, associate director at Simetrica Research Consultancy believes that social connection combined with the “warm glow” intrinsic to volunteering is what benefits the volunteers (Hopper, 2020). Ironic, but whether sorting cans at a food bank, walking animals at a shelter, reading to the elderly or tutoring a child, it is precisely the “escaping one’s own brain” that helps heal it.

The brain itself may play a part, as well, as the often-strenuous charitable activities (think painting houses and planting trees) relate to improved physical and, therefore, mental well-being. Research has yielded positive findings when studying the impact of healthy bodies on healthy minds, whether from the neurotransmitter dopamine released during exercise or merely the conscious satisfaction of a muscle burn.

But can volunteers absorb negative feelings from the people they help? A study out of Spain examined compassion fatigue which occurs when the compassion necessary to helping exceeds the capacity to regenerate, or “bounce back,” leaving caretakers feeling helpless (Gonzalez-Mendez & Diaz, 2021), akin to contagious sadness. The researchers explained that this arises from a “blurred self-other distinction” (Gonzelez-Mendez & Diaz, p.2); that is, the helper becomes compelled to withdraw from the situation in an effort to protect themselves from negative emotions. The answer: self-care. Altruism is admirable but going down with the proverbial ship is counter-productive, unhelpful to both the volunteer and the population in need. It is a delicate dance, deciding when to concentrate on the self or on others when overcoming trauma; self-awareness is key in finding the balance.

References:

Adams, R. E., & Boscarino, J. A. (2015, March 13). Volunteerism and well-being in the context of the World Trade Center Terrorist Attacks. International journal of emergency mental health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4358158/

Gonzalez-Mendez, R., & Díaz, M. (2021, September 1). Volunteers' compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and post-traumatic growth during the SARS-COV-2 lockdown in Spain: Self-compassion and self-determination as predictors. PloS one. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8409613/pdf/pone.0256854.pdf

Hopper, E. (2020, July 3). How volunteering can help your mental health. Greater Good. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_volunteering_can_help_your_mental_health

Lett, B. (2018, April 15). Study shows volunteering improves mental health in veterans. DAV. https://dav.org/learn-more/news/2018/study-shows-volunteering-improves-mental-health-veterans/

Ohrnberger, J., Fichera, E., & Sutton, M. (2017, December). The relationship between physical and mental health: A mediation analysis. Social science & medicine (1982). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953617306639?via%3Dihub

Silver, M. (2019, November 4). Veterans and PTSD: How volunteering can bring healing. WUWM 89.7 FM - Milwaukee's NPR. https://www.wuwm.com/news/2018-07-12/veterans-and-ptsd-how-volunteering-can-bring-healing

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (Reprint ed.). Penguin Publishing Group.

Reducing Burnout: The Importance of Quality Self-Care

Everyday living in 2022 is stressful and balancing family, work, and free time is no easy task. In an economy with record high inflation rates, and a healthcare system burdened with the many implications of the pandemic, rest and recovery is of utmost importance now more than ever. With the US dollar having significantly less purchasing power than last year, many people are attempting to overcome this by working longer hours. More hours spent at work means less hours spent on other aspects of our lives that we value much more personally. The cognitive dissonance that a person experiences because of this work-life imbalance can lead to feelings of burnout.

Burnout is the central theme of an article published by the Harvard Business Review. Author Monique Valcour characterizes burnout by three symptoms: exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Exhaustion is described as profound physical, cognitive, and emotional fatigue and is the primary symptom of burnout. Cynicism is psychologically distancing oneself from one's work because of feelings of disengagement and lack of pride. Inefficacy is having feelings of incompetence and lack of achievement or productivity. If you have experienced a multitude of these symptoms then there’s a good chance you've experienced burnout.

So what can we do to address or prevent burnout? Valcour suggests making changes to some situational factors in our lives that could yield positive results. For example, we must be better at prioritizing self care. Valcour states, “It’s essential to replenish your physical and emotional energy, along with your capacity to focus, by prioritizing good sleep habits, nutrition, exercise, social connection, and practices that promote equanimity and well-being, like meditating, journaling, and enjoying nature.” In my opinion, this is the most effective, yet also most overlooked method for criminal justice professionals to take care of their physical and mental energy.

One of the main expectations of criminal justice professionals is to put others first before themselves. This mindset is vital in the line of duty, however it can be problematic when it trickles into our day to day lives. Law enforcement officers don’t have the option of taking it easy because they are sick or they are having a rough week. It’s highly stressful to work in situations where every move you make is scrutinized and one mistake could cost you your job or even worse, someone’s life. Research indicates that law enforcement is a particularly stressful occupation due to a number of sources from within the organizational structure itself, such as role ambiguity, role conflict, lack of supervisor support, lack of group cohesiveness, and lack of promotional opportunities (Anderson et al., 2002; Gaines and Jermier, 1983; Toch, 2002). So not only do officers have to deal with on-the-job stressors like exposure to violence and suffering, but they also have to deal with organizational stressors as well. That’s why it is imperative to leave as much of the stress at work as possible and practice good self care while off the clock.

It's necessary to delineate the differences between good self care and bad self care. Dietrich and Smith (1984) shed light on the nonmedical use of drugs and alcohol among police officers, “alcohol is not only used but very much accepted as a way of coping with the tensions and stresses of the day” (p. 304). Reducing the norm of officers turning to these maladaptive coping mechanisms is an important step in the right direction towards practicing better self care. Having worked as a first responder for several years now, I’ve experienced how stress has trickled into my daily life and how I manage my own self care through effective coping strategies. One way I do this is by leaving work at work. Some examples of how I manage to leave work at work are by muting my email while off-duty, not overanalyzing the decisions I made and what I could’ve done better, and using my time off whenever I physically or mentally need a break. I also value my health very seriously as this is another way I manage my own self care. I try my best to eat well, get adequate sleep, and exercise daily. Even when I don’t feel like lifting weights or running, I make sure I get out for at least a 30 minute walk. During this time I will usually throw on a podcast on a topic I am interested in learning about so I am essentially learning while exercising.

In summary, work burnout is a very serious and common problem for a lot of people, especially criminal justice professionals. In order to prevent burnout from occurring we must prioritize effective self care through healthy practices rather than maladaptive ones. Even though I’ve listed what I’ve found to be successful for myself, it's important to note that every individual is different so they must find what works best for them. After all, we all have different needs and there's no one particular strategy that universally works for everyone.

Anderson, G.S., Litzenberger, R. and Plecas, D. (2002). “Physical evidence of police officer stress”, Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 399-420.

Dietrich, J., & Smith, J. (1984). The nonmedical use of drugs including alcohol among police personnel: A critical literature review. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 14, pp. 306.

Gaines, J. and Jermier, J.M. (1983). “Emotional exhaustion in a high stress organization”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 26 No. 4, pp. 567-86.

Toch, H. (2002). Stress in Policing, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Valcour, M. (2016, November). 4 Steps to Beating Burnout. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/11/beating-burnout

Utilizing Yoga as Treatment for PTSD

In this post, I will further the discussion that emphasizes the success of yoga as a treatment approach for individuals with PTSD. To start, I would like to express how I have personally seen yoga ease the tension that PTSD brings. As I have mentioned in many of my discussion posts, my parents are Bosnian genocide victims, and my mom still suffers from PTSD almost daily. She goes to yoga at least twice a week because she has really seen an improvement on her mental state. It allows her to disconnect from the world for an hour and focus on calming down her brain. Yoga is a powerful tool for all, but it is especially essential in treating PTSD.

For centuries, yoga has been used as a practice for the mind as well as the body (Rousseau, 2022). The process of directing your breath and energy to certain parts of your body is a beneficial skill to possess. In our book The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, Dr. Bessel van der Kolk (2014) discusses how yoga was more effective in treating PTSD than medicine (p. 209). This was my favorite part of the book to read. I consider myself more “holistic”. I will try every natural remedy for a headache before I take a Tylenol. I truly believe there are natural and holistic ways of healing what ails our bodies. Obviously, this is very dependent on the individual, and medicine is oftentimes needed. However, yoga can be used in combination with other treatments since it is a physical practice.

References

Rousseau, D. (2022). Module 4: Pathways to recovery: Understanding approaches to trauma treatment. Blackboard, https://onlinecampus.bu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-9960461-dt-content-rid-63971458_1/courses/22sprgmetcj720_o2/course/module4/allpages.htm

van der Kolk, B. A., MD. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin.

Embodiment and Breath Work as form of Therapy?

Embodiment and Breathwork as form of Therapy?

By Sarah Haas- April 16, 2022 CJ720

Although I certainly didn’t have a horrible childhood, as an adult, I can certainly look back and can say there were things of concern going on throughout my life. My parents were divorced and remarried and while there was undoubtedly love in the home there was also dysfunction. My mother was an alcoholic and Lord knows I love her (God rest her soul) the older she got, it seemed the meaner she got when she tied one on. She was intelligent, and a jack of all trades, there is literally nothing couldn’t fix, paint, decorate, refurbish etc... She went back to school in her 20’s and got her CNA but could never hold a job because of the alcoholism despite many of the Dr’s for whom she had worked, attempts to get her help because they believed in her and thought her work ethic (when not hungover) was impeccable. My stepfather, a man who liked to be in control of all things, ran the home with military structure, discipline (which I actually appreciate because it taught me to be structured and organized in my own life) and was the bread winner for our large blended family, he was very hard working in and out of the home. My father, a gentle man and gentle soul, has always been opinionated and hardworking but would never raise a hand to a woman, thus allowing himself to be walked all over by my mother and later in life, his (now ex) wife, my hateful stepmother, Kelly. Kelly was clinically diagnosed with Bipolar, which I did not learn until I was eighteen. I’ll spare the details and long-drawn-out story, but will just say this, when she was on her meds, she was one of the most generous, thoughtful and loving people in the world. When she was not on her meds, she had constant up and downs with manic and depression and I just remember always walking on eggshells not knowing what to expect each day; would she be in a good mood today, or would she be angry and hateful to one of us? It wasn’t until I was eighteen when my father kicked her out and filed for divorce that he confided in me that she was clinically diagnosed with bipolar and that he never told my brother or I out of respect for her; he tried to protect us from it as best as possible. I know now, that even though he tried his best, the constant need to walk on eggshells as a young girl has affected me into adulthood. I grew up a habitual nail biter, I also grew a tendency to be constantly nervous or anxious which bled into my 20’s and 30’s and affected many relationships both romantically and with friends/family. In 6th grade, my stepmom convinced my dad that I should go to a counselor because I was depressed, always had an upset stomach and was anxious often. This was all fine and dandy and I was willing to participate until she started showing up to my meetings and was in the room with me the first few appointments. In what world or who’s rational mind would a child be honest with their therapist about what was going on inside her head when the very person that was was responsible for manipulating her to say all her problems were about their alcoholic mother was sitting right next to her inside the therapist’s office? Even when she stopped coming into my meetings, I feared being honest because I thought my therapist would tell her or my dad. Kelly was 100% the very reason for my anxiety and depression, but if I’m being honest and humble, my mom and stepdad were also at fault for my anxiety and depression. There was physical and verbal altercations taking place more and more as we aged in their home, and they often intentionally were spiteful to my father regarding custody of us because once again, it was a way my stepfather had control over him and also they enjoyed hurting my father. I wasn’t the only child in either home, in my mom’s home, there were 5 kids, in my dad’s 3, so at times, when things were calm/normal for me, I would witness as they not so calm/normal for others.

Fast forwarding through a very long story because you by now get the point of the type of dysfunction in the home, I developed habits that weren’t healthy or safe. I became the child that constantly said thank you or sorry to everyone, out of fear that I would piss off the people in my life I loved (I still do it today, I’m a work in progress). As a young woman, I constantly felt self-conscious and responsible when I could sense tension in someone. I also habitually chewed my nails and cuticles, so bad to the point that my fingers would often be red, swollen and bleeding; ouch talk about sore! I began sleeping around looking for comfort and attention in all the wrong places. And sadly, somewhere around 17, I began to take the path towards bulimia, although it didn’t become an everyday occurrence or serious problem until I was in my early 20’s, thank you Army (the breeding of eating disorders in the military is a whole other topic in and of itself so I digress). Bulimia ruled my life for many years, and so many people had no idea, although there were a few who tried to talk to me about it and I told them they were wrong. I would binge and purge up to three sometimes four times daily and even though I knew it was unhealthy, dangerous and disgusting, I-JUST-COULDN’T-STOP! That is, until I found an embodiment coach and breath work!

At 36, I have only just begun to get a real grasp of my struggles with bulimia or my anixety within the last fifteen months. I have spent the last six years of my life trying to apply self-love habits and techniques to my life because I knew I was worthy and deserved nothing more than to see myself the way that so many others do, but nothing had really stuck consistently until my friend Chrystal Rose began her business and practice of embodiment through a group program called Pendulum at “The Self Love for Breakfast Club.” Although I am a huge advocate of embodiment, I would be remiss if I didn’t say age and maturity has something to do with my healing as well, because had I been introduced to this in my early 20’s I probably would have scoffed at it and laughed thinking how juvenile or weird because only “hippies” or “pot heads” practice that foo foo stuff (note, not my current thoughts, just what I know 20 something year old me would have said). Though I started the practice of self-love about 5 years ago, it wasn’t until this last year that I realized the true impact of my childhood into adulthood in such a negative way and really dove in and invested in true healing and self-love. I have a past riddled with anxiety and depression, yet I also learned to be resilient at a very young age because life goes on and I wasn’t just going to curl up in a ball and let life pass me by as a teenager or as a young woman in the Army. I’m very driven, I’m a perfectionist and, I would consider myself highly resilient because I have and will always want to be successful. I would also say though, that determination to just push through and be resilient can be a double edged sword, in fact, it fueled the fire for anxiety and depression that much more (though I didn’t realize that until my 30’s).

What is embodiment? Embodiment is just another name for being mindful, meditating, feeling and being in tune with yourself, etc.… whatever you want to coin it. It’s merely learning the ability to connect with the sensations inside your body and be fully aware and present (Madeson, 2022). This practice is not easy to learn immediately when our whole lives, we have been taught to just push through to meet the demands of life. In reality, that's the worst thing we could do, because as we know from our textbook, the body keeps the score and the body is constantly telling us something if we just stop long enough to listen to or feel it. Embodiment is unique, it’s quirky, it’s philosophical and it’s about feeling and learning things deep within our bodies that sometimes make us uncomfortable to realize. When practiced, it is one of the greatest things you can learn to practice for healing and inner peace which will open up doorways you never thought possible regarding trauma, anxiety, depression and in my case, an eating disorder. Embodiment, when practiced consistently and correctly, allows you to recognize the things (triggers) that elevate your energy and allow you regulate the emotions or responses to those triggers so YOU CAN HAVE BETTER CONTROL OF YOU RATHER THAN AN OUTSIDE FORCE. Now, by no means am I saying that people should discount psychological or psychiatric assistance altogether, I’m not a Dr. and this is something you should deeply research and consider before giving up therapy with a psychologist or psychiatrist vs. an embodiment coach. What I am saying, is that embodiment is just another tool that you can learn and add to your “tool belt” of life to be self-sufficient and independent with; learning to be aware, and to connect with your body to regulate your energy and feelings, it allows you to find balance and self-acceptance, it is a form of somatic psychology (Madeson, 2022). EVERY-SINGLE-THING we go through or witness in life, even if we do not think it is a big deal at the time, sits with us and can impact our physical, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual selves (Madeson, 2022). The practice of embodiment often uses movement such as dance or yoga, and breath work is an extension of it that. Once again, it allows us to release energy that we are holding in that can affect us negatively or positively. There are three type of sensory feedback systems that embodiment taps into: exteroception, proprioception, and interoception. Exteroception is sensing external environment through our senses of smell, sight, taste and touch. A great example of this would be meditating and practicing mindfulness. Proprioception is “sensory feedback of the body in relation to gravity” and “happens when neurons bring sensory information to the joints of the body and inner ear to the brain” (Madeson, 2022). A great example of this is yoga or dance. Interoception is our internal body sensory such as hunger thirst, pain or tension and provides “feedback about emotional experiences facilitated by sensory neurons that bring information to the muscles, organs and connective tissue to the brain" (Madeson, 2022). An example of this is being mindful of how much you eat.

I have sporadically been incorporating yoga in my life for the last 10 years but have only really begun incorporating it in my life three times a week since finding and investing in embodiment a year ago. I can personally speak to the healing it’s brought me physically with my body and emotionally how it’s improved my life. I'm becoming more in tune and comfortable with my true self, and now, I can acknowledge that the bulimia and nail biting were major signs of anxiety in my life (so if you see me as an adult with chewed off, swollen, red nails and/or a swollen face from bulimia, you will know these are telltale signs and a result of my anxiety spiking). I've made so much progress, I can regulate my emotions and responses and the things that used to stress me out or make me feel anxious, no longer bother me and physically (minus my torn rotator) my body is in such a great place; I've lost fifteen pounds and have kept it off and my joint and muscles feel so much better and healthier. Although I've made tremendous progress, I have so much work to do. Admittedly, I have shied away from some things/topics/feelings because they are uncomfortable and things I'm not ready to address yet, but trust and believe, I do intend to continue to make embodiment and yoga a priority in my life (because after all, I am a work in progress). Although I would not say I had a traumatic childhood or life, I do have experiences that shaped me and were deeply rooted in me causing me to act out or conduct myself in unhealthy ways over the last 17 years. Despite the healing and the paramount change embodiment and breath work has brought to my life, I know I have more growth and healing to do. No matter how old we get, we will all (always) have ways in which we can grow and learn. And today, I hope that if you are someone (who took the time to read this long blog) struggling with a painful or traumatic past, that you have found this blog insightful and inspiring; and know that your life can be changed through mindful practices and/or movement in embodiment. Cheers to a better, stronger, truer YOU!

Reference:

Madeson, D. M. (2022, January 17). Postive Psychology.com. Retrieved from Embodiment Practices: How to Heal Through Movement: https://positivepsychology.com/embodiment-philosophy-practices/

How do ordinary men become mass murderers?

When we reflected on the reasons for which ordinary men can become such ruthless killers and mass murderers, I feel that there were two very important psychologists whose work wasn’t mentioned as a possible further explanation and those men are Albert Bandura, an eminent figure in the social psychology field, and Muzafer Sherif, another eminent figure in the social psychology field and in the study of conflicts.

So, how can they be useful to the topic at hand?

Albert Bandura, when discussing moral standards found that it’s not enough to be well educated and morally just, in order to act morally. There’s an in-between which can be crucial to the way a person acts towards another (Celia Moore, 2015). He defines this concept as moral disengagement. Which is a cognitive mechanism by which someone, who has actual moral standards, can step away from them and act immorally without the feeling of distress that usually follows such acts. Moral disengagement is divided into eight specific mechanisms:

- Distortion of consequences

- Diffusion of responsibility

- Advantageous comparison

- Displacement of responsibility

- Moral justification

- Euphemistic labeling

- Dehumanization

- Attribution of blame

I’ll now offer an example for each of those mechanisms.

When talking about the distortion of consequences one might of someone who doesn’t control the use of the water they use because “nothing’s going to happen, this is not going to change the climate change crisis”, whereas diffusion of responsibility often comes in the form of “I shot those innocent people, but so did all my fellow comrades”. Whenever you split your responsibility with somebody else, your guilt lessens, and the more the people you split it with, the less the guilt.

An example of an advantageous comparison is “at least I was quick with killing them, others would have taken them their time with it and maybe even tortured them”.

Then, there's the one that most of the perpetrators of horrors against the Jew people used: displacement of responsibility, which we read in “it wasn’t my fault, I was just following orders”.

Moral justification is another tricky one, not uncommon during wars “I killed them to protect my people, so if I kill them first they can’t kill us”.

Euphemistic labeling comes near the distortion of consequences mechanisms, in this case, you dismiss your action as something not even worth blame, such as “I just merely insulted them, it was nothing”.

Dehumanization is one of the most dangerous mechanisms, fairly common during wars in general, and fundamental during the genocide of the Jew people: when you don’t see the other person as a human anymore, but as a mere object, or nothing more than an animal, you can easily become ruthless because you tell yourself that rules don’t apply anymore. You don’t feel guilty or horrified because you’re not really killing anyone, they’re just bugs, rats, snakes, they’re poisonous plants that need to be eradicated. When you don’t see one’s humanity, you don’t see the one thing you always share with everyone, the one thing that makes us all the same and that is the most dangerous thing.

And, finally, attribution of blame is pretty much self-explanatory. “They deserved this, they did this and brought all this upon themselves” (Celia Moore, 2015).

Sherif, on the other hand, becomes useful in explaining to us how easy can become to see someone as an enemy. A concept we already saw with Zimbardo’s experiment. We, as human beings, have a need to identify with something, in someone. We are our experiences, our relationships, and our roles in society. And we like to think the best of ourselves, regardless of our confidence, we’re like to think that between two groups, even if randomly chosen, our is the best, because that group, if we’re in it, automatically becomes part of ourselves and of how we define ourselves, so if that’s the best group there is, we’re the best.

Briefly put, the Robbers Cave experiment is set in a summer camp. Twenty-two eleven years old boys, with a similar background, were invited to a summer camp. For a while, they all slept in the same, big house, and relationships were allowed to prosper, friendships rose. After a few days, the boys were split into two groups, chosen randomly, and placed in two different camps. After a while, the two groups were put in competition with each other, using games in which they could confront one another. Almost immediately after, the competition and friction on the playfield escalated into mean and vengeful acts, which then escalated into violence. There was nothing that was dividing these groups, no morals, no race, no religion, no social-economic background, and yet, they started hating each other (Muzafer Sherif, O. J. Harvey, B. Jack White, William R. Hood, Carolyn W. Sherif, 1954/1961).

Sherif offers a further explanation of how conflict can literally birth out of thin air. And yet, Hitler did way more than just separate the groups. He yes, put these innocent people aside from society, but he also had laws created against them, he made sure people were indoctrinated against them, the regime taught people to hate them, to fear them. This only amplified the hatred, the mistrust in them, just because someone told them to.

I hope this can be useful to further consider other factors that can come into place when such horrific and tragic acts are committed.

References:

- Moore, C. (2015). Moral disengagement. Current opinion in psychology, (6), 199-204.

- Sherif, M., Harvey, O. J., White, B. J. (2013). Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation: The Robbers Cave Experiment. Literary Licensing.

Animals Help Us Heal

I have experienced significant trauma in my life. I didn't talk about it much when I was younger. I didn't want the attention. I don't want the attention now either. I talk about it now because it's part of who I am. I am a survivor who still tries every day to navigate her way through the jungle.

My pets have always been good for my mental health. Because of them, I am rarely lonely. The discipline of having to care for an animal keeps me moving forward, one step at a time. During times of intense stress, they calm me and focus me. These days I have two big dogs - Charlie and King. I couldn't be more grateful. The things I need, they need as well. They need to eat, go to the bathroom, and sleep. But, they also need to play. Today was a day without enough play. I am stressed and they can feel it. I will make it up to them tomorrow. I will allow myself time to play.

Halm, M. A. (2008). The healing power of the human-animal connection. American journal of critical care, 17(4), 373-376.

When Specialty Courts Fail

It is well documented that the United States incarcerates more of its population than any other developed country in the world. This fact alone has driven the need among criminal justice administrators and court systems to look at possible causes for the increase in incarceration rates and to find alternatives to prison terms. The solution in many jurisdictions has been the implementation of “specialty courts” that address societal issues that have made their way into the courtroom. These specialty courts involve working with defendants that have ended up in the criminal justice system due to drug or substance abuse issues, mental health issues, or co-occurring disorders. The premise of these courts is that these individuals are not criminogenic by nature and are instead stuck in a cycle of committing crime to support their substance abuse or their behavior is due primarily to an untreated mental illness. The court provides these individuals with the treatment they need and would likely not receive in prison in order to reduce criminal behavior and ultimately recidivism rates.

The first specialty court was established in Dade County, Florida in 1989 (Frailing, 2016). It was created as a specialty drug court to help individuals who found themselves in the court system for crimes such as possession, trafficking, or even theft to support a drug habit. Instead of these people pleading to their crimes and being sentenced to a prison term where they would receive little if any substance abuse treatment and counseling, the court brought all the parties together as a team to incentivize the individual into getting help for their underlying issues. What made this so unique was that it brought prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys, treatment providers, and defendants into a room to work together in a system that has always been at its core, adversarial in nature. Since this first court was implemented, it has seen incredible success rates prompting other courts to launch programs of their own. As of 2020, there are now over 3,848 different specialty courts in the United States that are working to address the underlying issues behind criminal behavior (Center, 2020).

Despite the successes these courts have seen in the past 30 years, there are always some that fail. What these failing courts have in common is that they often require defendants to plead to the crimes they have been charged with and offer very little sentence or probation reduction. For example, the federal court in the District of Maine currently has a program called SWiTCH (Success With the Court’s Help). This program has been known to be incredibly unsuccessful since it was established, and many people feel the program should be abolished. I investigated why this program was so unsuccessful when other specialty courts across the country have had the opposite results. Here is what I found:

The SWiTCH program is not a part of the actual court system and instead is a drug treatment program that individuals can enter while on supervised release. They must have plead guilty to their charges in court and served their entire prison sentence first before ever being considered for the SWiTCH program. This means their criminal record remains unchanged and the amount of prison time served is not altered. The only incentive for individuals entering the program is that if completed successfully, they will receive one year deducted from their supervised release. Meetings are held on a monthly basis where individuals check in with the judge, prosecutor, defense counsel, and their treatment provider (Justice, 2021).

As you may have guessed, this program offers little incentive for individuals to complete the program successfully, and the frequency of check-in meetings provides very little oversight for those struggling with substance abuse addiction. Fundamentally, this program was set up to fail. This program is the only type of specialty court offered in the federal court system in the District of Maine and demands a complete overhaul in order to be effective.

It is important for courts and communities who wish to address societal causes of criminal behavior to explore successful and unsuccessful specialty court programs to ensure they don’t encounter the problems seen within the SWiTCH program in Maine. As with most social justice programs, it is important that all facets are well researched prior to implementation in order to achieve success. Without it, you are doomed to failure.

Resources:

Center, N. D. (2020). Treatment Courts Across the United States. Retrieved from National Drug Court Resource Center: https://ndcrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2020_NDCRC_TreatmentCourt_Count_Table_v8.pdf

Frailing, K. (2016, April 11). The Achievements of Specialty Courts in the United States. Retrieved from Scholars Strategy Network: https://scholars.org/contribution/achievements-specialty-courts-united-states

Justice, D. o. (2021). SWiTCH (Success With The Court’s Help). Retrieved from United States Probation and Pretrial Services - District of Maine: https://www.mep.uscourts.gov/switch-success-court%E2%80%99s-help

Women Incarcerated: Basic Right Inequity

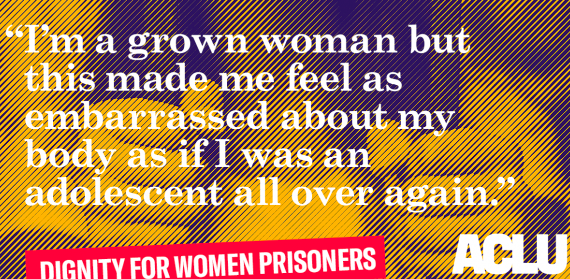

I think it is important to analyze and discuss the trauma that woman face within the carceral system. We always discuss the trauma that individuals go through before prison, but I think it is time we talk about the trauma that surfaces within the facilities. When it comes to women, they have different situational needs that differ from men. Before incarceration woman face many adversaries and it continues in prison. For women, it is important to realize that the most common reasons for women to commit crimes are based on survival of abuse and poverty and substance abuse. Their actions can be results of many different issues, including mental illness, trauma, substance abuse and addiction, economic and social marginality, homelessness, and relationship issues (1). Programs need to be focused on individualized reformation and focus on rehabilitation. A larger percentage of women are diagnosed with major depression and anxiety disorders, especially PTSD. Most women in the system (up to 70%, possibly even more) report histories of abuse as children or adults. Additionally, a greater percentage of women have histories of substance abuse than men (2). Statistics like these are reasons why women need equality but needs specialized focused programs. Unfortunately, women face trauma before, during, and after, it is an endless cycle.

I think it is important to analyze and discuss the trauma that woman face within the carceral system. We always discuss the trauma that individuals go through before prison, but I think it is time we talk about the trauma that surfaces within the facilities. When it comes to women, they have different situational needs that differ from men. Before incarceration woman face many adversaries and it continues in prison. For women, it is important to realize that the most common reasons for women to commit crimes are based on survival of abuse and poverty and substance abuse. Their actions can be results of many different issues, including mental illness, trauma, substance abuse and addiction, economic and social marginality, homelessness, and relationship issues (1). Programs need to be focused on individualized reformation and focus on rehabilitation. A larger percentage of women are diagnosed with major depression and anxiety disorders, especially PTSD. Most women in the system (up to 70%, possibly even more) report histories of abuse as children or adults. Additionally, a greater percentage of women have histories of substance abuse than men (2). Statistics like these are reasons why women need equality but needs specialized focused programs. Unfortunately, women face trauma before, during, and after, it is an endless cycle.

Within the correctional system there is still many states without legislation or mandates on period products. In 2017, only 12 states and the District of Columbia have passed menstrual equity laws that require no cost menstrual products in state prisons, which means most incarcerated people in the United States still have limited access to the period products they need.

Many of these women must beg, borrow, or make their own sanitary products, this proves that there is no dignity, compassion, or humanity in the system. Over the years pads and tampons have become weaponized in the system. “I know women who made products out of shreds of clothes or stuffing from inside their state-issued mattresses and were subsequently penalized for destroying public property.” This isn’t only embarrassing but it carries great health risks as well. These makeshift products can lead to toxic shock, infections, and infertility (3).

In Connecticut, commissary sold a pack of pads for $2.63. Prison jobs in Connecticut they pay as low as 30 cents per hour. “Assuming that a woman has a five-day menstrual period, each month and changes her tampon at 8-hour intervals, the maximum time suggested by gynecologists, a woman using tampons at NCCW is spending 25% of her annual salary on feminine hygiene products” (3). With that wage any of these individuals cannot afford it on top of other necessities like doctor’s visits, acetaminophen, or a phone call to a loved one. Some women even turn down visits with their family or even turn down visits with their attorneys, which can have a huge impact on their time incarcerated within the whole process (3).

In Connecticut, commissary sold a pack of pads for $2.63. Prison jobs in Connecticut they pay as low as 30 cents per hour. “Assuming that a woman has a five-day menstrual period, each month and changes her tampon at 8-hour intervals, the maximum time suggested by gynecologists, a woman using tampons at NCCW is spending 25% of her annual salary on feminine hygiene products” (3). With that wage any of these individuals cannot afford it on top of other necessities like doctor’s visits, acetaminophen, or a phone call to a loved one. Some women even turn down visits with their family or even turn down visits with their attorneys, which can have a huge impact on their time incarcerated within the whole process (3).

When it came to asking guards for a menstrual product, there is a certain power dynamic between the guards and inmates that created a sense of humiliation even thought this is a basic need. Sometimes guards would use manipulation and blackmail against the inmates and used their power to go above them. According to a 2019 Period Equity and ACLU report, a Department of Justice investigation found that correctional officers at Tutwiler Prison for Women in Alabama coerced incarcerated people to have sex with them in exchange for access to period products (3).

This even is affecting young women too, there is a youth rehabilitation and treatment center in Geneva. This place houses girls anywhere from age fourteen to nineteen. Even they had to pay for their own feminine hygiene products. The young girls can’t earn money while in the home, so it is entirely up to the families. The problem rests on the fact that some families are poor and cannot afford to travel to visit them let alone afford these sanitary products for them.

Every individual has a right to personal hygiene whether you're incarcerated or not. Giving woman sanitation products and focusing on women health is a major factor that needs to be included in personal treatment plans for women in prison. The deny of these basic rights reinforces any kind of powerlessness you have ever felt in your life.

Resources

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2021). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach.

Lee, J. (2021, July 1). 5 pads for 2 cellmates: Period products are still scarce in prison. The 19th. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://19thnews.org/2021/06/5-pads-for-2-cellmates-period-inequity-remains-a-problem-in-prisons/?amp

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 4: Implementing Psychology in the Criminal Justice System. [Lecture Notes]. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Is it trauma-informed?

In some of my previous discussions, I have described my experiences as a juvenile detention officer and what kind of programs the facility has. It seemed that the more I learned throughout this course, the more surprised I was with the lack of trauma-informed programs and practices at my place of work. Considering the frequency with which I see kids who have a plethora of traumatic experiences and mental health problems, I wanted to examine one program we run in the facility and analyze how trauma-informed it truly is.

Generally speaking, the programs that are run within our facility are a means to occupy the minors, keep them active, or fulfill some type of school-based requirement as a primary goal. It appears that having well-rounded, trauma-informed, and healing programs is secondary to that. Along with programs such as sex education and big brothers big sisters, our facility has a yoga instructor come in every week day to lead an hour-long class. Sometimes, the hour of yoga is the only structured physical activity the minors have throughout the day, and therefore, it fulfills their physical education requirement. At times, the youth aren’t engaged in the yoga. Often times, especially if yoga is in the morning, they will just lay there and sleep- claiming that they are “meditating.” Personally, I think it would be helpful to have more discussion with the kids about what kind of impact the yoga has on them and how they can use the time to be mindful, as “Even though a yoga instructor may try to proceed with the best of intentions, they may not realize that without proper training on trauma-informed yoga, they could be leaving certain youth feeling disempowered and marginalized” (OGyoga).

The TIMBo program has three objectives of: providing accessible tools for coping, gain awareness of the body, and begin a process of transformation (Rousseau & Jackson, 2014). The program I am familiar with is essentially just a yoga class, without identifiable objectives, and rarely any discussion with the participants or indication that the class is meant to do more than help them be relaxed or flexible. Benefits of trauma-informed yoga include emotional awareness, increased self-esteem, improved ability to identify negative behavior, improved conflict resolution (OGyoga), decreased anxiety, decreased trauma symptoms, and increased self-compassion (Rousseau & Jackson, 2014). Our current program could provide those same benefits if instructors and staff were trained and youth were engaged in a more meaningful and knowledgeable way.

Trauma-informed services are safe, predictable, structured, and involve repetition in order to avoid triggering trauma reactions, support coping capacities, and provide some kind of benefit from the service (Rousseau, 2021). Overall, I think taking the time, efforts, and resources to update the existing program would be worth it. Often, we are told to be mindful of trauma that the kids experience, but we are given training that seems inadequate and do not provide them with programs that are substantial enough to address their trauma. Especially since incarceration itself can be traumatizing, we need to maximize the potential of existing programs and implement others in order to best serve the youth and help them heal. Although the current program is safe and structured, I do not think it is trauma-informed. The purpose of the program and structure of it was not made to intentionally respond to and aid the youth in this way, therefore, the youth cannot gain the same benefits they would from a truly trauma-informed yoga class.

References

Burrell, S. (n.d.). Trauma and the environment of care in juvenile institutions. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources/trauma_and_environment_of_care_in_juvenile_institutions.pdf

OGyoga. (2018). Benefits of yoga for youth who have experienced trauma. Retrieved from https://www.ogyoga.org/resources/2018/2/8/benefits-of-yoga-for-youth-who-have-experienced-trauma

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 4: Implementing psychology in the criminal justice system. Retrieved from https://learn.bu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-9312167-dt-content-rid-57732979_1/courses/21fallmetcj725_o2/course/w4/metcj725_ALL_W4.html

Rousseau, D. & Jackson, E. (2014). yogaHOPE: Healing ourselves through personal empowerment. Retrieved from https://learn-us-east-1-prod-fleet02-xythos.content.blackboardcdn.com/5deff46c33361/3915210?X-Blackboard-Expiration=1639450800000&X-Blackboard-Signature=%2FsKuLigz%2FZWXITxDNSLpkjtyQsl%2FBRRz2u1Ua8JV5wo%3D&X-Blackboard-Client-Id=100902&response-cache-control=private%2C%20max-age%3D21600&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%2A%3DUTF-8%27%27w4_read_TIMBo2014.pdf&response-content-type=application%2Fpdf&X-Amz-Security-Token=IQoJb3JpZ2luX2VjEGcaCXVzLWVhc3QtMSJHMEUCIDbX7i4%2FUdN1FyWpa4YvUA9OXdUWl4PbvWyihcCdYrTbAiEAgzEuYiNoBEETgHcE5W%2FAIfLBVCtk44SAPgoZLEr8BXsq%2BgMIUBACGgw2MzU1Njc5MjQxODMiDOWGmjYfScfEwRbnZyrXA%2BUpqWiEio%2FC%2BaPuLxxgnsNDeuROz8TDyhwPRSZP8%2BgarYqIVnP%2BJQ1H08%2Be23OZkZRCFEDk%2FlL%2BCq%2BSpwrv7hdrE8Mw6ZYFwZigud6ucpTF9HdSTOdW6OWsViAZlfBQcjE0SVMtSmdMo5BSkONjpgTbvrZNZ1pJQCPAQ6KWtOsnLUwfyFAf1srlwDrWe1aakVRaNpkJVTFEnt4PIciappAAGDW4p2ZbRuualWc0%2BAY4GSAFjFoC24n%2FdGM6GTgm5c1dP%2BildfpepwI6pmGDWlpxkRp2bv755IKUFkx5SSsXnoL9V%2F2sDCeWlSNnvWcnfsMLEZpz3Bx0wSKqBwHkvpMdSOUfj0oeEudLKErXYI5rOvwvUSOPlEqJbOPDYdQC2oZqOCYSZZRwrTApECD%2Bsze5WVuRhtViQ7msg6Rzu39WNB%2BzK8sxPAEtbHrzTWUbZds08QFicUXoi6dUsP9GYfZBCAt%2BTeVTO6Iv8rKCtawxjhC3Sl7qGJM5b3Jjo2hSTq%2FGwg8qE%2BOlWV82QhKrL7WAT0n6LWAzjdrVdJ9uT8d%2F7CNU%2FAc27B%2F8PC8s5ZYQJmZfD0cNwxle1Fl9GWOMtVFZwL8Tl%2BZeK6SbFZCeMfBgVF99dSy5ADCeoN%2BNBjqlAe5F9vyFs%2FXdR47oEzyIn3tB4ex%2FZQgbrWMPtFJEO1nvgeH%2BCM58RVLGBpreCahDgI%2F2fZUyBvvtiUtK78cGNk28xgyhU1FAlIi6faiErKlXRkxeTTkyFY72M8ZL8%2Bn2jsDt%2F%2F44%2BRzD389ka3tygofYS9fikZe4B17XSxM%2BQXpm2BPsPu1Zu8g2CPadYi8Hs0nOZKZ%2Feur%2BftQVw1LLz7NeUjArMQ%3D%3D&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Date=20211213T210000Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=21600&X-Amz-Credential=ASIAZH6WM4PL7XQYCGEE%2F20211213%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Signature=ccfca75afac21ad3161a33d2f1a6ec305280acea1baa94efe52aab641f2a2314

Grief: Is It Possible to Have a Worthwhile Life After Sexual Abuse?

Rape, by definition, is an attack or an attempted attack that involves unwanted sexual contact with penetration, in a relationship between an offender and a victim, where the victim lacks the consent (Bartol, 2020). This definition seems to be very straightforward, however, it does not fully explain why a plethora of victims never report this act of sexual violence but go through mental, physical or both traumas and grieve. What does stand behind this complicated grief? Why are some treatments not effective? What are those psychological tricks that sexual offenders apply to their victims so that they question whether it is possible to live a worthwhile life or not after the sexual abuse they were exposed to?

Before shedding some light on the complexity of sexual-related crimes, it is worth it to look at some important facts: the victimization data on adult females within relationship factors. Precisely, 24.4 % of sexual assaulters are strangers, 21.9 % are husbands or ex-husbands, 19.5 % are boyfriends or ex-boyfriends, 14.6 % are acquaitances such as friends or neighbors and 9.8 % are relatives (Bartol, 2020). Thus, one can conclude that the majority of rape cases are indeed conducted by strangers and those who victims might have a relationship with. That being said, there is a puzzle being raised: why don’t rape victims report to the police about what happened to them and prefer to grieve in silence? Clearly, those rape cases that involve intimate partners might have a logical explanation since victims have fear to confess that their husband or boyfriend has exposed them to sexual violence, especially if an offender and a victim turn to have a family together, and a raped woman is willing to protect her children. However, what about those cases when a stranger is involved? What does stop a female to report the sexual crime if there is no personal connection to the perpetrator? To answer these questions, it might be informative to analyze the tapes of 911 calls that were made despite the unwillingness of victims to report.

Now, if we refer to 911 calls, it might be noticed that the relationship between a perpetrator and a victim is not that complete and obvious as it seems from the first sight. To illustrate this, an array of 911 calls show that a victim usually blames herself for the sexual violent acts occurred because, first, most likely this victim meets her perpetrator in the bar, next, typically the rape itself happens in the victim’s house, and finally, the victim emphasizes her fault since she was drinking alcohol that led to these adverse consequences (Sexual Assault, Media Education Foundation). From the tapes’ perspective, it becomes clear that the victim’s role in this relationship tends to get dual. In others words, we get a victim, a woman who realizes that she was exposed to sexual abuse and violations of her rights, and an “unnamed conspirator” who keeps whispering to this woman “listen, this is you who drank with him, invited him to your house, drove with him in your own car, and eventually brought him to your house”. The concept of an “unnamed conspirator” (Munch, 2012) is not new, it was developed by Anne Munch, an advocate for victims of sexual assault and stalking, who discovered the presence of the third side existing in the relationship between a victim and an offender. This theoretical discovery in the field of sexual-related crimes and trauma is very crucial because it demonstrates a strong influence of this “unnamed conspirator” that we can call as some sort of moral rules “follower” that dictates a victim to obey them, and since they were infringed, a victim experienced a terrible feeling of fault and sacrifices herself as a martyr who is exposed to suffering. And this is the moment when the grief comes into play. A victim is convinced by this “unnamed conspirator” that she has broken the moral code, and she prefers to isolate herself from society, thinking that this society will actually judge her since she was this initiator of the sexual act, she is convinced that it was not sexual assault or rape, it’s her who should be blamed in every single consequence. Thus, applying this theory we can conclude that a perpetrator exposes his victim not only to physical violent acts but also to psychological traps knowing in advance that the victim will “interact” with the “unnamed conspirator” and this element of their relationship will contribute to putting the victim into endless cycles of fault and grief, meaning there is a potential guarantee that she won’t report about him to the police. This scenario serves as a example of a violent culture that keeps growing especially in the community of young females who study at college (indeed, this victim profile is the most frequent one for perpetrators to deal with since young females find themselves irresponsible in a sense due to drinking in a bar and as a result going through basically negative consequences they have created themselves - this is a typical logic of a victim that was exposed to sexual violence by a stranger). This leads us to horrendous traumas that young women experience by binding themselves with “grief handcuffs” from their young age.

After this theoretical analysis, one should refer to traumas themselves. Particularly, this can be the rape trauma syndrome or post-traumatic stress disorder (Bartol, 2020). “Grief” argument is exactly related to this psychological traumatic experience because the main syndromes go around anxiety, feelings of helplessness, shame, depression or the development of phobias. However, it also does not exclude the physical malfunction either since rape trauma sydnrome includes sexual dysfynction as well. Now, the treatment for traumas linked to sexual abuse might seem to be simple to follow as it is usually advised to seek for a trauma therapist; join some supporting groups in order not feel alone or disclose to those ones who a victim trusts in order to feel support and overcome this crisis. This is why it is worth it to look at the Survivor Therapy Empowerment Program that was elaborated by Dr. Walker (2013). This program is based on the principles of trauma and feminist theories where she claims that the trauma healing should be based on safety planning, empowerment via self-care since it is a priority to take the power back to a survivor, overcoming depression to optimism and developing cognitive clarity (Walker, 2013). This treatment approach seems to be quite essential to apply for the victims of rape or domestic violence, and it was successfully developed within verbal therapeutic approaches that indeed can be a decent treatment for those who needs support and sense of belonging to the community to eradicate the feeling of loneliness.

However, these techniques are not necessarily effective and simple to apply for those victims who are trapped inside the “grief cycle” shaped by the “unnamed conspirator”. In order to find the proper treatment for these specific cases, one should understand what the grief cycle is. For example, the model of Kubler-Ross (1969) includes 5 stages of grief which are denial (the stage that helps the victim to survive “loss”), anger (the stage when the victim lives the terrible reality), bargaining (the stage of false hope), depression (the stage that represents the emptiness the victim feels) and acceptance (the stage when the victim tries to start living with what has happened). Having this knowledge in mind, it might be possible to consider another type of trauma treatment that involves 2 phases of therapy: medical and psychological. From the medical perspective, the prescription of medications such as sedatives or anti-depressants influences the victim inside while assisting in functioning the nervous system properly via supporting the sleep process and suppressing the grief during the day time. When it comes to the psychological approaches, counselling still might be a beneficial verbal therapy that as we can see from the above mentioned programs is capable of producing positive results. Nevertheless, an amalgam of both approaches should be applied since the grief cycle is not just a complex phenomenon consisting of different stages but also a mental trap that victims are exposed to in sexual violence and it requires a complex treatment that doesn’t leave aside neither the physical nor mental elements of a female body.

Works cited

- Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2020). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach.

- Kubler-Ross E. (1969). On Death and Dying. 50th Anniversary Edition.

- Munch A. (2012). Sexual Assault: Naming the Unnamed Conspirator. Media Education Foundation.

- Walker L. (2013). Domestic Violence and Survivor Therapy Empowerment Program.