CJ 725 Forensic Behavior Analysis Blog

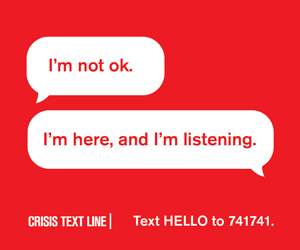

We never leave you on read

Hi, my name is Randi. Thank you for texting in tonight. It takes courage to reach out. Tell me more about what is that has led you to text in. I am here to listen to you and support you in any way that I can.

According to Mental Health America, more than 44 million adults have a mental condition and 1 in 5 reporting that they have unmet needs ("The State of Mental Health in America", 2018). Some are uninsured, some do not have the means to access care such as transportation or lack of services offered within the area. Regardless of the reason, many Americans are suffering daily with approximately 123 committing suicide a day making suicide the 10th leading cause of death regardless of age in the United States ("Suicide Statistics and Facts – SAVE", 2018). One visionary, Stephanie Shih saw the need for a place to go for those experiencing trauma and mental illness that was quick to respond and listen, be supportive, and point others in the right direction so they can receive the help that they need. Shih, working for a nonprofit DoSomething.org, a group that sends texts to local youth encouraging them to become active volunteers within their community, received a text stating “He won’t stop raping me”, a few hours later another text “R u there?” (Gregory, 2015). There was no protocol for these messages. Shih brought this to her C.E.O. Nancy Lublin and two years later Crisis Text Line became the first and only free national 24/7 crisis-intervention hotline that operates exclusively through text message. What started in two cities (Chicago and El Paso) quickly spread to reach all 295 area codes within four months with zero marketing and faster growth than when Facebook first launched (Lublin, 2015).

The idea is simple, a texter texts the number 741741 and within minutes a trained crisis counselor will respond through an online platform with a casual greeting and a willingness to help that surprises many texters. There is no judgment, no problem too small. The system has grown drastically since its birth five years ago in August 2013 and has sent out more than 88, 217,385 text messages ("Crisis Trends - Crisis Text Line", 2018). The beautiful thing about a text-based system is that it is private and nobody will hear you talking. The texters identify remains anonymous, texters can talk to a trained crisis counselor in a crowded room and nobody will know, and they receive the immediate help they need. A girl can sit down at lunch and text in about her eating disorder and her friends are none the wiser. A teen can text in their room at night about their father physically abusing them and the father won’t know, but that teen is reminded that the violence isn’t their fault and are given resources to help them fight their way out of a terrible living situation. There are resources for veterans, homelessness, free legal help, mental services, LGBTQ+ based services, bullying, anxiety, depression, grief, substance abuse, the list goes on.

Many of the texters text in saying things like “I don’t want to live anymore,” “I want to die.” The crisis counselor quickly builds rapport with the texter and does a risk assessment to identify how close the texter is to take their own life. According to 2015 TED talk, Nancy stated that on average there are 2.41 active rescues a day, meaning that the texter was in the process of taking their own life or was planning on doing so within the next 24 hours and the crisis counselor could not get the texter to guarantee their safety (Lublin, 2015). Nancy goes on to say “The beautiful thing about Crisis Text Line is that these are strangers counseling other strangers on the most intimate issues, and getting them from hot moments to cold moments…” (Lublin, 2015). These crisis counselors are volunteers that complete a 40-hour training and dedicate a minimum of 200 hours to helping others. They are trained to bring texters from a hot moment to a cool calm through active listening, and collaborative problem solving (“Crisis Text Line”, 2018). They log in from their own personal computers and handle multiple conversations at one time to make sure that each texter receives all the care and love they need.

Not only is the Crisis Text Line directly impacting individual lives, but the data that is being collected and publicly shared is also making a huge difference in the way we think about and track crisis. The personally identifiable information is scrubbed and the data is shared to assist other professionals to write policy and increase awareness nationally. The data is being used to make the world a better place and using social media platforms to reach as many people as possible. Algorithms in the system take keywords such as “depression” and “suicide” and bump them to the top of the queue so they can reach a crisis counselor faster than a texter who may just be having a bad day and needing an ear to listen. Regardless, each texter will receive a crisis counselor as fast as the counselors can. Many times, it may take time depending on how big of a ‘spike’ the server is seeing. Recently a post on social media went viral: “Did you know that if you text "Home" to 741741 when you are feeling depressed, sad, or going through any kind of emotional crisis, a crisis worker will text you back immediately and continue to text with you? Sometimes it’s best to just talk it out with someone who has no personal bias. Many people, especially younger ones, prefer text to talk on the phone. It's a free service to anyone; teens, adults, etc. who live in the US. Depression is real, you're not alone. 💚 You just have to copy & paste” and the amount of texters has reached a number with 4 December 2018 being the second highest traffic day in the system has ever seen ("Crisis Trends - Crisis Text Line", 2018).

It is good to hear that you are feeling calmer and that you have the confidence to make it through today. Remember, we are here 24/7 if you are ever in crisis again. Take care.

Crisis Trends - Crisis Text Line. (2018). Retrieved from https://crisistrends.org/

Lublin, N. (2015, May). How data from a crisis text line is saving lives

. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/nancy_lublin_the_heartbreaking_text_that_inspired_a_crisis_help_line?language=en

Suicide Statistics and Facts – SAVE. (2018). Retrieved from https://save.org/about-suicide/suicide-facts/

The State of Mental Health in America. (2018). Retrieved from

http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/issues/state-mental-health-america

Psychology of Terrorists

While conducting research on the Unabomber, along with the final week’s readings on terrorism. The psychology of terrorism, and those who are able to carry out such acts intrigued me for further research. It is an interesting debate that various researchers make different claims for their opinion in the mind behind terrorism.

The first expert Martha Crenshaw, in 1981 published her research on terrorism paired with certain psychological factors underlying it at its core. Crenshaw (1981) asks why, “ the individual takes the first step and choses to engage in terrorism.” To this she claims that, “terrorism is the result of a gradual growth of commitment and opposition, a group development that depends on government action. The psychological relationships within the group- the interplay of commitment, risk, solidarity, loyalty, guilt, revenge, and isolation- discourage terrorists from changing the direction they have taken (Crenshaw p.397, 1981).” This article thinks of terrorism mainly as a group. Where Crenshaw utilizes ideas like groupthink and group dynamics as a factor in terrorist psychology. This was definitely a major factor when watching recruiting videos in ISIS and similar groups. People are responding to the call to become something larger. While Crenshaw’s statements remain true today, the shift in terrorism seems to have moved away from large groups operating under a single name towards one cause.

In Kruglansky’s article The Psychology of Terrorism he discusses many risk factors that, in part, cause individuals to join terrorist groups. He clearly distinguishes that there is no one overarching personality type that all people who join terrorist groups fit under. The personality types he mentions he considers to be a “contributing factor” instead of a “root cause” for why individuals resort to terrorism (Kruglansky, 2006). First, he mentions relative deprivation or a desire for what an individual perceives to have. Relative deprivation, or the discontent with ones self relative to others does not need to be present in every case, however it does demonstrate a level of desire for achieving a goal and, in their mind, the best way to attain that goal was through terrorism (Kruglansky, 2006). Kruglansky (2006) also states that those in favor of right-wing authoritarianism are another common theme for individuals willing to join terrorist groups. These results reflect a study on Lebanese individuals who reacted in favor of aggression towards the US. Simultaneously, their results also reflected a subsequently in high support of right-wing authoritarianism.

Mortality salience is the final factor that Kruglansky (2006) identifies as another contributing factor for an individual being drawn to terrorism. Mortality salience is defined as anxiety over ones demise. Humans try to make themselves immortal by leaving a legacy. Humans are aware of their death, unlike other animals. In a study Kruglansky cites, Iranian students, who on average are exposed to more death, are reminded more of their own death and thus demonstrate higher levels of support for suicide bombings (Kruglansky, 2006).

Other authors, armed with extensive research create their own models of traits that may push or pull individuals towards joining terrorism. Haslam mentions emotion as a pushing factor (Haslam, 2006).He believes that dehumanization effects individuals, as their mistreatment builds resent over time. This is trait is also accompanied by degradation and humiliation that would drive an individual away from society into a terrorist group.

Other authors continue to find trends building an extensive profile of risk factors. Victoroff’s argument shares many of the previously stated characteristics but adds a couple such as narcissism, often coupled with a lack of empathy is also noted to be personality traits that could push individuals who are at risk into joining a cult but also possibly a terrorist group (Victoroff, 2005). He also recognizes other broad psychological theories that could push individuals like apocalyptic theory, or expectation of ones imminent demise. Paranoia theory, claims that individuals with political grievances use terrorism against persons who may not actually be a threat. Other factors addressed by authors are alienation, which can occur at an individual level as well as in a group setting. An individual can remove himself from society, as can a group (Victoroff, 2005). The separation of ones self from all others and society has cultivated thought to join extremist groups or become a lone wolf.

In Great Expectations and Hard Times by Brockoff, Kreiger, and Meierrieks, they connect education as a risk factor to terrorism. Some of their findings show that education makes terrorism less likely by teaching the population to combat the propaganda. However, there is also concern that education is creating high-level operatives capable of higher capacity operations (Brockoff, Krieger, Meierrieks, 2015). The article concludes by mentioning that sole strengthening of education in less developed countries will not necessarily help stop terrorism. Instead, the promotion of education, coupled with efforts to improve poor socioeconomic and demographic conditions will attempt to mitigate the risk of individuals joining terrorist groups.

Similarly to many mental health cases and crime, there is no one root cause, but instead multiple risk factors that cause a push towards a certain behavior or action. However, through these risk factors researchers are able to identify those at risk and hopefully mitigate future terror attacks and threats.

References:

Brockhoff, Sarah, Krieger, Tim and Meierrieks, Daniel. 2015. Great expectations and hard times. 59 (7): 1186-215.

Crenshaw, Martha. 1981. The causes of terrorism. Comparative Politics 13 : 379-99.

Haslam, Nick. 2006. Dehumanization: An integrative review. Vol. 10.

Kruglansky, Arie W. & Fishman, Shira (2006) The Psychology of Terrorism: “Syndrome” Versus “Tool” Perspectives, Terrorism and Political Violence, 18:2, 193-215

Victoroff, Jeff. 2005. The mind of the terrorist: A review and critique of psychological approaches. Journal of Conflict Resolution 49 (1): 3-42.

Incompetency to stand trial

One topic which I found most interesting throughout this course was that of incompetency to stand trial. Incompetency is a mental state which makes one present in the body, but not the mind. The standard in which someone is deemed competent to stand trial is if "they have sufficient present ability to consult with their lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding.. and a rational as well as functional understanding of the proceedings" (Bartol, 2016, pg. 221). Anyone who is considered incompetent will not be tried.

In competency is interesting because it's not only based on mental or emotional characteristics. It can also be utilized if someone has a lack of understanding of the court process, such as personal rights, or functions of members of the court proceedings. This to me is an interesting point based on the fact that so many people can claim incompetency off of this alone. Evaluations are necessary to ultimately decide who can stand trial, and who may not be able to. In some cases, multiple hearings may be held to determine competency... One fact that stood out to me was "nationwide, only four out of every five (80%) of the evaluated defendants are found competent" (Bartol, 2016, pg. 222). (Retrieved from my original discussion post)

I found this particularly interesting because I have a rape case pending trial, and the defense attorney is pushing incompetency since the defendant is a senior citizen and has some mental health issues. As promised, in my first post, I said I would update the class on the status of the, pending the rapidness of the court case. As I assumed, the defense attorney’s first action was to plead incompetency due to age induced mental illness, as well as pre-existing conditions which was the reason the offender was in the halfway house to begin with. I was browsing through some of the defense lawyer’s paperwork which he submitted, and one area in which he stated the defendant suffered from is PTSD.

Without being too specific, my offender is a senior citizen who served in the Vietnam War. His mental history suffered drastically upon his return from the war. Since a young age, he battled PTSD from being involved in such a life changing event. This then toppled into his excessive use of drugs, inability to keep a steady income, homelessness, and eventually criminal activity which led to him being court ordered to a group home in our town. He has an extensive history involving hospitalizations for his PTSD which was actually coupled with psychosis. The trauma in which he endured followed him throughout his adulthood, and ultimately plays a factor in how his court proceedings will continue. It’s a viable defense for incompetency, and will certainly be taken into consideration as it moves forward in the judiciary system.

In this case, mens rea, or the state of mind of the offender, is being taken into the question. “Most U.S. jurisdictions allow mental health expert testimony to refute mens rea, whereas some jurisdictions restrict such testimony to the insanity defense” (Berger). In Rhode Island, this is a feasible thing for them to use as defense. The lawyer wants to argue that the offender lacked the state of mind to realize what he was doing due to his long term PTSD. This has been interesting to follow, especially after medical records came back proving that some sort of penetration had occurred. In the victim maintaining that it was not consensual, and the defendant does not plead guilty, it will be interesting to watch this develop further!

Source:

Bartol, C. R. & Bartol, A.M. (2016). Criminal Behavior: A Psychological Approach. 11th edition.

Berger, Omri, et al. PTSD as a Criminal Defense: A Review of Case Law. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 1 Dec. 2012, jaapl.org/content/40/4/509.

Punishment. The New Rehabilitation

The prison systems in the United States are one of the most unsuccessful systems in the world. For an institution to be up and running even though it consistently fails the people and what it stands for is blasphemy. The whole concept of prison is to not punish, not to destroy families, not to cause mental health issues or even make money. The purpose of prison systems is to rehabilitate those who have bad habits, issues, or make mistakes. If criminals are put in jail to be punished, the government and the criminal justice system needs to state that and make that rule rather than just having this unwritten rule that causes criminals to suffer.

American prisons are filled with millions of people across the country. The prison systems are not organized and actually cause more harm than good. Once an offender enters the prison he or she joins rapist, murders, thieves, and many other types of criminals, which leads to another issue. Should a person who goes to prison for selling drugs be in the same institution as a murderer? Should a person who has known nothing but to fight to solve social problems be arrested and sent to prison with a rapist? Does not matter the level of the crime a person commits, they are going to be sent to an institution where even the biggest and baddest are taken down. This low-level criminal is going to have to fend for themselves and most likely become worse than how they were before entering. Prisons should organize their inmates according to the crime committed, I feel like this approach would be better fitting than just throwing a person where ever there is room.

Inside of prisons, the correctional officers have a reputation for being mean and manipulative for self-gain. Correctional officers do have a tough job and they must protect themselves physically and mentally, but there have to be better ways that correctional officers maintain order and are apart of the rehabilitation process. They are very important and have a huge effect on inmates because these people are the only ones dealing with the inmates on a day-to-day basis. Bettering correctional officers would be another step for rehabbing inmates since that is the “purpose” of prison.

Not expecting all of the prison system to be fixed, but there are little things that are possible to change to make the rehabilitation process more efficient. There are too many offenders who serve time, are released, and end up back in prison. For a lot of individuals, prison has become a home, a lifestyle, or even a habit because of an immense amount of time spent there. These individuals are not released feeling better about themselves or willing to change. Most of them know they will go out, continue the lifestyle they lived before prison, make the same mistake and end up back in prison.

Overall, there needs to be change, some type of change in the way the system rehabilitates people, or the system could change the rule from rehabilitation to punishment. That way at least the people will understand, it does not seem like the people are being lied to, and the system does not appear to be doing whatever it wants. There are too many people in these institutions for the institution to be failing. Maybe we should try a different type of institution for criminal rehab. If there were any other institutions with these failures, it would be shut down almost instantly. The prison institution should be held to the same standard.

Evaluating the Role of Trauma: Case of Cyntoia Brown

In recent news celebrities such as Rihanna and Kim Kardashian have reignited a case that was sentenced on August 25, 2006. This is the case of Cyntoia Brown. 16-year-old Cyntoia was tried as an adult and found guilty of first-degree murder, felony murder, and especially aggravated robbery and was subsequently sentenced to life. But does this case warrant it's newfound attention and outrage? In 2004, she murdered 43-year-old Johnny Allen in his home after he had solicited her for sex. She described his narcissistic attitude and the jump from how one moment she felt comfortable and in the next innate fear. Throughout the night he bragged about being a sharpshooter in the army and showed her his gun collection. She states he went to grab something, she perceived it to be a gun and she preemptively shot him. It is undeniable that she committed this offense but there’s something about this case that is unsettling, to say the least. The following analysis is based on the documentary, “Me Facing Life: Cyntoia’s Story” produced, filmed and directed by Daniel H. Birman; adapted and produced for BBC by Tony Lazzerini.

Dr. William Bennet, a forensic psychiatrist from Villanova University, conducted an evaluation that assessed Cyntoia from pre-birth to age 16. His evaluation uncovered a severe history of sexual trauma coupled with early development issues as well fetal alcohol syndrome disorder, induced by her mother drinking “a fifth” every day while she was pregnant. In her earliest years between the ages of 6 months and 3, she lived with reportedly seven or eight caretakers and was kidnapped by a family member. Attachment theory seemingly applies here. She was never able to form a healthy attachment to any mother form, even her adopted mother. She was adopted at the age of two as her mother was unable to successfully care for her attempting to balance working, attending beauty school and caring for an infant. She is quoted in the documentary as stating that she “didn’t even know how to make a bottle.” Her adopted mother had children of her own who Cyntoia reports being compared to. Her husband was apparently abusive towards Cyntoia where she states, “That’s what he’d say when he hit me because I like it.” In terms of familial history, her biological grandmother became pregnant with her mother after being raped by a man hired by her husband in retaliation for leaving him. Cyntoia’s mother testified in court that she suffers from bipolar personality disorder, suicidal manic depressive disorder as well homicidal thoughts after she was raped. She has attempted suicide several times and reported her biological mother shot herself in front of her when she was young as well as the inclusion that her aunt and grandfather had also shot themselves. Prior to Cyntoia meeting Johnny Allen, she describes a man named Garion, with whom she engaged in some sort of relationship. He kept her with him bouncing from hotel to motel and sexually and physically abused her, threatening her with a gun if she left. He eventually graduated to selling her on the street and forcing her to engage in prostitution. During her evaluation, she shows the psychiatrist her “sex list”. this list contains 36 men that the 16-year-old has had sexual encounters with. She describes a list of 36 men where: 21 were forced and counters, 22 she did not know, 3 were relatives, 28 were associated with the bad experience, 4 were for prostitution and finally only 9 of the 36 encounters used protection.

The culmination of all of these repeated and exacerbated traumas led to a manipulative, possessive, paranoid, unstable 16-year-old girl. Dr. Bennet describes that the effect these traumas had on her caused her paranoia and an “affect of instability” wherein she was unable to process the situation where she perceived intense fear and acted on it. Cumulative risk model would define this level of trauma with the limited protective features as severely debilitating to a healthy or normative developmental trajectory. Her abandonment and trust issues along with her mistrust with men and relationships are defined by a personality disorder according to Dr. Bennet. He never defines which disorder, but her traumas affected her view of the world, how it relates to her and how she relates to her world. She discussed her view of men in the documentary stating she believes they’re “selfish and justify their behavior because they’re men.. no they just want to be admired and accepted, and whys that my problem that is my problem, for 18 years I’ve wanted to be accepted.”

Based on her history and her genetic, environmental and psychological traumas, Cyntoia seemingly never had a chance. All of this in conjunction with the way her case was handled is infuriating. Detectives Mirandized her and questioned her while she was under the influence and her confession was admissible in court after she stated she didn’t know she had the right to remain silent or against self-incrimination. (Which also brings up the question of her competency.)

Even barring these traumas, children are incapable of making decisions the way we normally expect an adult would. Trying her as an adult further this young woman's trauma and victimization, ensuring she will never be rehabilitated. this case a pitta mise is so many sexual trauma victims that go unnoticed by society until it’s too late. There needs to be some other way to protect children that get exposed to this level of risk. It isn’t their fault and treating them as though it creates more problems and adds to the existing issues. Until our justice initiative evolves to rehabilitative focuses, there will be many more disenfranchised children that fall victim to a broken and cruel system.

So, does this case warrant it's newfound attention and outrage?

Birman, D. H. (Producer, Director)(2010) Me facing life: Cyntoia's story [Documentary]. United States: Daniel H. Birman Productions, Inc.

Trauma and Self Care

Imagine every day you wake up and put on a shiny badge that not only represents the safety you will bring to your community, but also represents the sacrifice you are willing to make for the citizens you protect day in and day out. In my own personal opinion, there is nothing more rewarding than taking pride in yourself, in the work that you do/your career, and for the family you have raised and protected. It seems as though that when entering law enforcement, you have a strong urge to make a difference in the lives of those who may be less fortunate, or are maybe just having a really crappy day. Unfortunately, as time progresses, police officers/law enforcement officials have been painted in a bad light due to all of the controversy over police officer on civilian shootings. Through all of this tragedy, I think some individuals forget just how difficult it is to be a police officer. Who are we to comment on what they do to protect themselves in a situation we have no idea about? An experience such as this can be considered a incidence of trauma. Police officers/law enforcement officials are presented with trauma on a regular basis whether it is responding to crime scenes, car accidents, assaults, child abuse cases, disputes, domestics, being subjected to physical confrontations, internal investigations, or anything that can be considered a traumatic experience (Renteria, 2009). Renteria (2009) encapsulates perfectly why it is so important for law enforcement to engage in self care by stating: "Police work is a physically and emotionally draining job. Repeated exposure to negative images and interactions affect the overall physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual well being of police officers spilling over in to their personal lives drastically impacting their families".

I believe that far too often, police officers are unaware of the impact trauma can have on their own lives until it is far too late. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (2017), "almost 1 in 4 police officers has thoughts of suicide at some point in their life. And in the smallest departments, the suicide rate of officers is almost four times the national average" (NAMI, 2017). This means that almost 25% of all police officers have contemplated suicide, which is astounding in the worst way. As if that was not frightening enough, NAMI (2017) stated that "more police die by suicide than by homicide: the number of police suicides is 2.3 times that of homicides". Clearly, there needs to be something implemented to decrease these statistics significantly.

With the help of NAMI, the road to recovery for police officers is finally being paved. In order to help our brothers/sisters in blue that are in need, we as citizens need to be informed far more on trauma, vicarious trauma, and ways that PTSD and other mental health issues that result from trauma can be prevented in law enforcement. Within police departments, there is also much work that can be done to recognize trauma, and also how to deal with that trauma. As a male dominated job, self care and being in touch with your emotions is greatly frowned upon because men are supposed to be tough and not let anything get to them - newflash people...ITS 2017 AND ALMOST 2018! Gone are the days that someone should be ashamed of what they feel and why they feel it. Men have emotions too, and its time that they are taken care of, especially in law enforcement. In order to do so, I believe that each police department/law enforcement agency should have an onsite therapist that specializes in law enforcement trauma and PTSD, and how to manage/cope with these aspects. They will help implement mental health awareness/wellness programs, and also serve as the mental health incident commander in instances that could potentially involve someone with a mental illness, or some form of trauma (NAMI, 2017).

If we want law enforcement officers to protect and serve for us, their mental health needs to be a first priority. f you can admit that you need help, that is the first step in your journey to recovery, whether you suffer from PTSD or alcoholism. No matter how much money someone may have, how cool their job is, or what color their hair is, every person is a work-in-progress. There is always room for improvement, even in law enforcement. In a nutshell, every person on this earth needs a helping hand at some point in their lives. "Once we can understand this concept, we can accept our weaknesses, learn from them, move forward, and open ourselves up to positive changes. Embracing change allows us to be more willing to seek out the resources that can help improve our self awareness. It is never too late to make changes that positively impact our lives, as well as the lives of those who are closest to us" (NAMI, 2017).

NAMI. (n.d.). Retrieved October 10, 2017, from https://www.nami.org/Law-Enforcement-and-Mental-Health/Strengthening-Officer-Resilience

Renteria, L. (2009, March 31). Law Enforcement Personnel and Family Life. Retrieved December 15, 2017, from http://www.lawenforcementfamilysupport.org/family-resources.php

The “New Nature” of Terrorism

The topic of terrorism has been on everyone’s minds for some time now, especially since the terrorist attacks on September 11th, 2001. This event caused a great deal of trauma to the United States, officially launching us into the War on Terror and proving that the United States was susceptible to attacks on its own soil. For one of the first times in history, planes were used to launch an international terrorist attack, but a previous terrorist attack that used planes effectively brought international terrorism into the spotlight.

The first of attack of this kind took place in 1972, when members of the Palestinian terrorist organization Black September kidnapped and murdered members of the Israeli Olympic team. The members were taken from the Olympic Village in Munich to waiting helicopters. They were then flown to an air base west of the Olympic Village, where the West German police were waiting. Once the aircraft the terrorists required arrived, they inspected it and discovered they were being tricked. A gunfight between the terrorists and the police ensued, killing several police and many of the attackers. The Israeli hostages were all bound together inside the plane, and for the time being they survived. However, one of the surviving terrorists threw a bomb inside the helicopter, killing all but one hostage, and another terrorist shot a gun throughout the inside of the helicopter, killing the last hostage. (cite)

Many scholars claim that this attack was the beginning of “modern terrorism”. It was the first attack to receive widespread television coverage both during and after the attack, and it was the first time that aircraft was used to conduct an attack. I, however, tend to believe that terrorism is cyclical, and that the term "modern terrorism" really means that old practices are reemerging. Suicide bombing is nothing knew, and large, impactful attacks are also not new. Additionally, it is entirely possible that terrorism is “modernized”, but this could have begun at several different points: it could have begun with the 1972 Munich Olympic attacks because of the highly public nature of the event, it could have begun with the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 because, at least to Americans, it was a direct attack on the government, or it could have begun with another event.

One way in which terrorism is definitely modernized is through recruitment. Due the prevalence of social media, terrorists are able to recruit over long distances and they have greater access to susceptible individuals. Using social media as a recruitment tool is rather ingenious because it allows leaders to target disenchanted individuals and use them as pawns in their plans. Additionally, if Middle Eastern terrorists target westerners, it allows them a certain degree of anonymity as westerners would draw less attention when walking in a place crowded with other westerners (a suicide bomber walking into a crowded place).

How to stop terrorism is one of the biggest issues the world is facing. Because there are so many threats and so many ways of carrying out these threats, it is almost impossible to know what to do. I think the first step would be to stop viewing terrorists as irrational individuals. These people have a goal or a cause for which they are fighting, whether it is religious, political, or something else. Because they are fighting for something, they are inherently rational beings: they believe in something and they are willing to fight, or die, for it.

A second step would be to adopt a universal definition of terrorism so that every single nation is on the same page as far as what is terrorism versus war. For example, and I do not claim to have the answer to this, do North Korea's threats to the United States count as acts of terrorism or acts of aggression that precede a war? This is a tough question because the definition of terrorism is so vague that it can count as both terrorism and aggression. Or do aggressive acts count as terrorism? Surely sometimes they do, but where is the line drawn? This is where the universal definition would be helpful, because if we can define terrorism and put a face to the name, we can begin to take actions to counteract it.

Although terrorism is a problem the world throughout, it has served the purpose of uniting most people against a common enemy. The shared trauma of people and nations that have been attacked by terrorists serves the purpose of bringing everyone closer together and unifying them against terror. Although there is no solution to terrorism, and its cyclical nature may prove impossible to defeat, there is a rather strong force fighting against terrorism. Although it is hard to believe that anything good can come from a terrorist attack, terrorism has brought many people and nations together in an effort to combat it.

Intro to Psychopaths

The appealing look with above average intelligence, balanced with the ability to stay focus and organized even in under pressure. Also, equipped with excellent communication skill that allows an individual to comfortably fit in and draw the attention of a particular crowd, these would be a perfect resume for the most wanted employee nowadays. What happens if these traits come with the catch like emotionally detached, untrustworthy, sensation-seeking, and criminally versatile? It would only set a conquest to failure for the company.

Nonetheless, the personality traits are common among psychopaths in which most people believe as the cold-blooded serial killers. While it is partially correct, these qualities are also can be found among higher level management, which can be referred to corporate psychopaths. While many would raise their concern about the presence of psychopaths stressing out the criminal proclivities, some would also believe that these individuals play a significant role in society

According to Christopher J. Patrick, Don C Fowles, and Robert F Krueger, in their research on defining the concept of psychopathy, a psychopath would exhibit a pathological syndrome of emotional detachment, impaired remorse with a deficit in emotional response and behavioral control. In addition, psychopaths only account for 1-2% of the overall population. The assessment of psychopathy in an individual can be given by employing Hare Psychopathy Checklist which consists 20 items to measure personality traits and behavior. The maximum score of the assessment is 40 and depending on the country; one can be labeled as a psychopath with a score of 25 for the United Kingdom and 30 for the United States. Although, the validity of Hare Psychopathy Checklist has been in question over the year due to the lack of evidence and valid reasoning to support the method in the assessment. It is argued that some of the criteria meet the characteristics of other psychoses.

According to Hare, the prominent feature of a psychopath is the absence of empathy, a successful development of emotional functioning ranging from the expression, recognizing, interpretation, and the response of the emotion. Which makes psychopath unable to detect empathy via verbal or non-verbal communication. In contrast, some researchers argued that psychopaths may have the capacity for cognitive empathy, allowing them to recognize and respond to the emotional from their casual encounter. However, the psychopaths would likely disregard or exploit the feeling for a personal gain. There is also evidences that psychopathy can be inherited and manifested in the early life. While genetics were responsible for a personal development, it is noted that the environmental factors have significant impacts in creating psychopaths.

Based on the criteria in Hare Psychopathy Checklist, some of the notorious serial killers like Ted Bundy, Harold Shipman, and Charles Joseph Whitman may fall under psychopath’s syndrome. Although using the same items, one can argue that not all psychopaths are violent. For example, a British journalist, John Ronson, stated while the lack of empathy is the prominent feature of a psychopath, in the right dosages, other personality traits would create a psychopath with CEO quality that can run a worldwide company. Although, it would also include the individual in other professions. The great decision often requires sacrifices that may occur beyond business world including military, medical, and firefighting. It can be settled by someone who was confident, ruthless and focused under pressure. In specific, some of the attributes such as the need for stimulation when combined with high determination, while under pressure, would bring profession like surgeon or firefighter into a successful path. Another example of positive traits of psychopathy that can be found in some profession is a higher military position. Despite the contradiction of wreaking havoc at enemy’s line, a decisiveness upon decision is needed to protect thousands of lives while keeping the enemy at bay.

In conclusion, it is worth noting that the emerging role of a psychopath, either positive or negative, run concurrently. Exploring the world of psychopathy is necessary to unveil the adaptive nature and the purpose of a psychopath in reality. The result may be beneficial in changing the perception in viewing the individual with empathy impairments and to the extent of the contribution on society as a whole.

Persecution, Mass Murder, and Trauma

By Sara Azam

I am ashamed to say that only recently I became aware of a crisis that has been happening for the last several years, where a government is single handedly denying a population of people basic human rights, status as citizens, and essentially, responsible for raping, murdering and setting ablaze entire villages in an effort which can only be described as ethnic cleansing or complete and utter genocide. I am of course referring to the Rohingya people of Myanmar.

The Myanmar government, military and Buddhists monks believe that this particular ethnic group has illegally occupied the Rakhine state and are trespassers and actually belong in the neighboring country of Bangladesh. However, the reality is that for most of the Rohingya, the Rakhine region is the one and only place they have ever lived and have called home. They were born there and their parents before them. So how can it be that all of a sudden they are foreigners in their own home?

This dispute has caused a cataclysmic upheaval and now the three parties previously mentioned, the government, military and Buddhists monks, are actively sanctioning the deliberate removal of the Rohingya people through any means necessary including murder. Because of this, the Rohingya are fleeing by hundreds of thousands, on foot, with whatever personal possessions they can carry, to safety in refugee camps. Otherwise, they are subjected to beatings, torture, witnessing the executions of their parents, children, husbands, brothers, fathers, and loved ones and gang rapes of their daughters, mothers sisters and wives, and having their homes and villages completely annihilated by watching the military set them on fire. There have even been reports of children and babies being thrown into those fires.

Yet, even with all of these reports, government officials claim these are lies. The government also highly censors the news and social media within the country so that the majority of Myanmar citizens believe the Rohingya are actually terrorists setting their own villages on fire and then running away. Anyone who dares mention even the word “Rohingya” in a social media post is immediately censored and then stalked and intimidated by government officials.

Now imagine the trauma. The trauma those who have fled and survived such egregious acts and witnessed such atrocities will experience. And the horror is not yet over. They must survive in the refugee camps. For 10-year-old Jena, she is now the sole provider for her family. This little girl’s father was executed and mother is too ill to care for the family so she must go to the forest, collect firewood and sell it in the market to help feed her family. In another case, a mother in the camp must find a way to help her 6-month-old son survive because he is so malnourished that he weighs as much as a newborn baby. And there are countless other cases of the harsh realities of persecution and refugee life, not just for adults, but for at least 360,000 children. That figure is simply staggering. We already know the effects trauma can have on adults and adolescents and how it can cause varying levels of, and sometimes severe mental illness and even lead to a life trajectory of engagement in crime. The question now is how will it affect these children? And better yet, what will we, as citizens of the world watching, do about it?

References:

Asrar, S. (2017, October 28). Rohingya crisis explained in maps. Al Jazeera. Retrieved from http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/interactive/2017/09/rohingya-crisis-explained-maps-170910140906580.html

Bangladesh: Hundreds of Thousands of Rohingya Seek Refuge From Violence in Myanmar. (2017, November 21). Médecins Sans Frontières – Doctors Without Borders. Retrieved from http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/article/bangladesh-hundreds-thousands-rohingya-seek-refuge-violence-myanmar?source=ADD170U0U00&utm_source=AdWords&utm_medium=ppc&utm_campaign=Google&utm_content=nonbrand&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIqsuH25-G2AIV2AiBCh2itwowEAAYASAAEgJbRfD_BwE

Myanmar Rohingya: What you need to know about the crisis. (2017, October 19). BBC News Services. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41566561

The Rohingya crisis. (2017). Cable News Network. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/specials/asia/rohingya

Woodruff, B., Romo, C., Francis, E. (2017, December 6). For Rohingya and supporters, a fight for survival on the ground and on social media. ABC News. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/International/rohingya-supporters-fight-survival-ground-social-media/story?id=51418912

Men & Women Inmates Are Not The Same!

We addressed the issue involving male and women offender treatments. Many people argued it should be equal or else it is unfair. “What about equality for all!” The thing is as much as we try to be seen as equals, there is still some bias factor that holds us back while trying looking at everyone the same. In reference to criminal treatments, how can we hold both genders accountable to the same treatment if their brains are wired differently? Yes you can argue there can be similar situations in the workplace, but then again, women and male officers handle situations completely differently but still manage to get the task done. It does not matter how it is done, as long as protocols are followed and no boundaries are crossed. We all are more effective when we find a way that works best for us as individuals.

I argued that women offenders are very emotional beings in comparison to their male counterparts and tend to be better situation thinkers due to high levels of interconnections with the hypothalamus. This lead me to believe a treatment program where females could remain in contact with outside family would help the recovery progress and lower distress levels even if it’s only for a short frame of time. Some people believe this could become a bad idea as males will want to partake in such a program as well. In my opinion, the women’s brain is capable of handling this task and demonstrating results. If we implemented a program as such, I would bet results would be more beneficial for females because males tend to be more of an aggressor and don’t tap into that emotional side as frequently as the opposite sex. For the male counterpart, it would be more of a reward than a treatment method. Yes this can make things more difficult for correction personnel, but perhaps the improvement in women offenders is worth the risks. For those individuals who have committed more serious heinous acts, we need to be able to evaluate their ability to partake in such a program and may involve further psychological testing. The key will be to look at risk assessment before we develop any treatment program.

Men and women prison typically function differently however there are an estimated thirty percent that do not feature programs that are conducive to women (Umar 2016). To be able to develop such a model, we need to learn more about the women and men’s brain in order to give an accurate assessment and guideline to develop a successful treatment. This may not be the answer to dealing with mental illnesses in a corrections setting, however just like all the theoretical perspectives, this could be one piece to the puzzle tapping into the biological side of the brain. This will involve biologist, forensic psychologist and criminalist getting together and collaborating to create the best efforts for offenders to hopefully offer great success in the long run. Perhaps these studies will also enhance our understanding of what brain functions contribute to the act of committing illegitimate acts.

References:

Umar, E. (2016.). Men’s Prisons vs Women’s Prisons. http://correctional-medical-care.com/mens-prisons-vs-womens-prisons/