CJ 725 Forensic Behavior Analysis Blog

Fighting Mental Illness in Law Enforcement

Violent crime would generally be considered a life-altering event. It scars, it molds, it changes people whether they like it or not. This is why therapists and psychologists play such a large role in the prevention and study of crime because it has so much to do with the mind and its triggers. But when the people responsible for bringing justice take on the burden of these crimes, who takes care of them?

According to Dr. John Violanti, a researcher at the University of Buffalo, it is estimated that approximately 15% of law enforcement officers suffer from PTSD symptoms. This number is likely much higher due to the stigma of mental illness as a member of law enforcement. “This is dangerous”, says Dr. Janet and David Shucard. PTSD affects executive mental function and when the brains that handle weapons and are supposed to protect the public aren’t working at their best, people get hurt. Police officers, in particular, make decisions involving deadly force. Having quick and calculated mental functions is important to not killing someone innocent.

The American Psychological Association offers many solutions for those who have been formally diagnosed with PTSD. They’re variations of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy which focuses on changing the connections the mind makes with certain behaviors and feelings. It’s designed to remodel the pathways of the brain and change dangerous and dysfunctional associations. Cognitive Processing Therapy focuses on the traumatic event itself and aims to redefine the pain one associates with it. The treatment is typically delivered over 12 meetings with a psychologist. Cognitive Therapy is another variant and is designed to modify the memory of the trauma. This is an intensive treatment plan and requires over three months of commitment to weekly meetings and group events. The last variant of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is Prolonged Exposure Therapy. The hope of this form is that through gradual exposure to the memories in safety and with the aid of a psychologist, one will learn that the trauma itself cannot hurt them. The pain is only present in the actual event, not in its memory. This form also requires a three-month treatment period with more frequent check-ins as remembering traumatic events can make one more vulnerable to panic attacks and triggers as they begin their healing process.

PTSD as a concept is continuously being studied. Researchers from across the globe devote their lives to understanding how to fix minds that have experienced trauma. Members of law enforcement are particularly vulnerable to developing PTSD by the nature of their profession. They are trained to avoid their natural instinct to run from danger and instead tasked with standing up against it. This is why PTSD symptoms should be carefully monitored before they develop into something more. Members of the New York State Department encourage the use of trauma-inoculation training and trauma awareness so that officers can take their mental health into their own hands. It is by helping the people that are trained to help us, that we can make the world a better place.

Sources

David Shucard and Janet L. Shucard, “Electrophysiological and Neuroimaging Studies of Cognitive Control: Introduction to Special Issue,” International Journal of Psychophysiology 87 (2013): 215–216, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.03.009.

König, J. (2014). Thoughts and Trauma – Theory and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder from a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Perspective. Intervalla: platform for intellectual exchange, 2, 13- 19.

T.J. Covey, Janet L Shucard, John M Violanti, and David Shucard, “The Effects of Exposure to Traumatic Stressors on Inhibitory Control in Police Officers: A Dense Electrode Array Study Using a Go/NoGo Continuous Performance Task, International Journal of Psychophysiology 87 (2013): 363–375, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.03.009.

Waltman, S. H. (2015). Functional Analysis in Differential Diagnosis: Using Cognitive Processing Therapy to Treat PTSD. Clinical Case Studies, 14(6), 422-433.

The “Infotainment” of Mental Health and Crime

When you think about mental illness and how it is portrayed in media, it seems as though many people would instinctually lean towards fictional television shows like “Criminal Minds” or news broadcasts discussing the mental state of the most recent mass murderer or criminal dominating the news cycle.

The best way to describe the sensationalized nature of mental health in media? Infotainment.

Infotainment is described as “television or radio programs that treat factual material in an entertaining manner, as by including dramatic elements” – it is “both informative and entertaining” (Dictionary.com).

However, by framing serious crimes and mental illness in this “infotainment” perspective, it may do more harm than good. In a study of newspapers in the United Kingdom on how they reported mental health, Chen & Lawrie (2017) found that more than 50% of all daily news reports on mental health were depicted in a negative light, often associating those with mental illnesses as violent in comparison to those who are physically ill. The news has a “preferential reporting for sensationalist stories depicting individuals with mental disorders as being aggressive, dangerous, and unpredictable” (Chen & Lawrie, 2017, p. 308).

Chen & Lawrie (2017) state that news sources (newspapers, TV news channels, social media, etc.) hold a key role in how society learns about the world around them. This has been seen before with the campaigned "War on Drugs" and the efforts to lock up juvenile "superpredators" - where politicians and media sources campaign on and distort an issue within the criminal justice system. For the majority of people who may have limited exposure to mental illness or the criminal justice system, these news and media sources are how they learn. As a consequence, a social wariness is encouraged towards those with mental illness or with a criminal background.

It may be a fair assumption that most people will not turn to scholarly journal articles to inform themselves of current events or issues. Instead, they will do what is most convenient: turn on their TV or open up their phone to their favorite news app or social media site. Over 80% of all Americans get their news from their smartphone or other device (Shearer, 2021). Often, the goal of these media sources is to gain the most clicks and to keep users scrolling. To do that, eye-catching titles, flashy graphics, and other forms of clickbait are used. Through this, real-world issues like mental health and crime often become distorted to something more dramatic or polarizing for the sake of public consumption, rather than as issues that require real attention and solutions. The conversations about how those with mental illness may also have corresponding drug or alcohol addictions, may have been victimized by others, or who might otherwise be at some sort of social or economic disadvantage compared to larger society are subsequently missed.

While this “infotainment” approach towards mental health and crime can help to bring awareness to societal issues of health care and the criminal justice system, a careless approach to these discussions can be a slippery slope. As Dr. Rousseau (2021) states, “stigma erodes confidence that mental disorders are real, treatable health conditions” which, in turn, can create real “attitudinal, structural, and financial barriers to effective treatment and recovery.” People may view mental illness as something to fear or lock away, when it instead be more productive to view individuals with mental illnesses and criminal histories as individuals in need of help and rehabilitation. A large portion of America's prison/jail population is comprised of individuals with serious mental illness that impact daily life and functioning, and these individuals often end up back in a carceral setting again after release (Baillargeon, 2009). This may be in part due to the fact that many of these people do not get or have access to consistent mental health treatments after release, so a cycle is created.

When it comes to real-world news consumption, people should be careful to understand that many of these news channels or sites are trying to get you to click on their pages – and that individuals may have to go to multiple sources to get a more wholistic view of the situation in a way that is sensitive to the nature of mental health and trauma. Instead of solely turning to their favorite news channel, individuals may also stop to consider that people and their mental health are more than just a headline or a sound byte – they may want to turn to scholarly publications and studies to better understand the conditions that are being discussed, or look into the programs and polices that are in place to deal with these situations.

To help alleviate some of the stigma surrounding mental health in fictional media (TV shows and movies) perhaps rather than always connecting mental illness to violent crime and the negative consequences, we should start emphasizing more sensitive or realistic depictions of mental health in a way that is still entertaining to viewers. To start, some of my personal recommendations would include Marvel’s Jessica Jones (Netflix), Shameless (SHOWTIME), or The Queen’s Gambit (Netflix).

Overall, there is much work that needs to be done to connect the realms of entertainment and information to avoid the distorting effects of infotainment. Perhaps by opening up these discussions of how mental health and the criminal justice system are portrayed in media and news, we can get one step closer towards destigmatizing these issues and creating real change.

Resources:

Baillargeon, J., et al. (2009). Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: The revolving prison door. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 103–109.

Chen, M., & Lawrie, S. (2017). Newspaper depictions of mental and physical health. BJPsych bulletin, 41(6), 308–313. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.116.054775

Dictionary.com. (n.d.). Infotainment. Dictionary.com. Retrieved December 11, 2021, from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/infotainment.

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 2: What is Mental Illness [Lecture Notes]. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Shearer, E. (2021, January 12). More than eight-in-ten Americans get news from digital devices. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/01/12/more-than-eight-in-ten-americans-get-news-from-digital-devices/.

Self- Care: Deeper than Stress

By: Deborah Vincent

About two years ago, if you had asked me what self-care was, I probably wouldn't be able to answer that. But when you ask someone what exactly stress is, their first answer is often about something they are struggling with externally. Certainly, there is a general definition of stress. It’s defined when “environmental demands [exceed] the capacity for effective response” (Parsonson & Alquicira, 2019). Unfortunately for professionals, this can often be their workplace and home life. When that stress is at its utmost height, we begin to experience burnout; “emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment (Parsonson & Alqucira, 2019). As professionals, this can be detrimental to patients but also to the mental and physical health of the professional. The risk of this for professionals, such as therapists, is that they may find themselves unable to regain energy and focus without a break (Pope & Vasquez, 20005). In an early study, it was found that among therapists working with sex offenders, “half had experienced emotional hardening, rising, and confrontation; more than a third suffered frustration with society or the correctional system; and one quarter experienced burnout” (Parsonson & Alquicira, 2019). This can look different in everyone. You may no longer see the value in your work. You might even begin to ignore crucial information with patients.

So, what should one do? Can we use self-care to alleviate something deeper than stress?

For starters, I know it is so easy to bury yourself in your work. We can sometimes use work as an excuse to not deal with the outside world. But you are more than just your work. You might be a mother, a wonderful cook, quite the explorer. Who are you outside of work? Who do you wish to become?

Is it clear now that there is so much more to self-care than removing stress?

Self-care is about taking a moment to center yourself, realizing what’s important to you. But it goes hand in hand with being mindful of yourself, your thoughts, your intentions. Being self-aware of your emotions.

...

A great book, "Mindfulness for Beginners", was introduced to me by a professor roughly two years ago. It consists of multiple activities. Here are just two activities that I think truly made a difference in my approach to life.

I hope they can do the same for you. Take a moment, 5 minutes or so, to yourself and pick one of these activities.

- Take 5 minutes out of your day and write about the person in your life that you appreciate. Why? What would you tell them if they were standing here with you?

- “Morning Pages” Write down everything you're thinking. EVERYTHING. Do this for as long as you think you can go. Now reading back at your page, what do you notice? Any patterns?

How do you feel? I hope this is something you can adopt into your everyday life. It should be clear now that relieving stress is more than just self-care but also about “[maintaining] equilibrium or homeostasis within a self-system such that the professional self does not impinge on the personal self and vice versa” (Bressi & Vaden, 2017).

References:

Bressi, S.K., Vaden, E.R. Reconsidering Self Care. Clin Soc Work J 45, 33–38 (2017). https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1007/s10615-016-0575-4

Parsonson, K., & Alquicira, L. (2019). The Power of Being There for Each Other: The Importance of Self-Awareness, Identifying Stress and Burnout, and Proactive Self-Care Strategies for Sex-Offender Treatment Providers. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 63(11), 2018–2037. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X19841773

Pope, Kenneth S.; Vasquez, Melba J. T. (2005); In: How to survive and thrive as a therapist: Information, ideas, and resources for psychologists in practice. Pope, Kenneth S.; Vasquez, Melba J. T.; Publisher: American Psychological Association, pp. 13-21. [Chapter]

self-care

As a society we are often taught to constantly go-go-go. America's working class is said to be the "backbone of the economy", it is the land of success and opportunity (“5 traits of America’s working class - CBS News”, n.d.). A working mindset is almost handed over to us at a young age to adopt and apply to our individual lives so that we are motivated to fit into the common mold and path of school, careers, family, and retirement.

Personally, being related to and knowing such successful individuals, it is not a rare feeling that you should constantly be working towards your future. We may be taught to associate free time with laziness and negativity, however, that is not the case. I say lightheartedly, that I am convinced my dad is not capable of sitting down and doing "nothing". It is extremely hard for him to relax because of how he was raised and also the generation he was born into. My dad was born in the 1960s so as many of us know, identifying and/or managing stress, anxiety, depression, and many more related mental health disorders were not talked about or treated like they are today. Thankfully, I was taught how important it is to take the necessary time off to self soothe and re-energize so that you can put forth your best work and attitude utilizing your healthy mental and physical energy. I find it beneficial to dissociate and know when it is time to put a topic to rest for the night. After a stressful day I have a couple of things that help me re-coupe, for one, I love having face masks and calming essential oil scents to choose from. Also taking a hot shower and changing into something comfy always helps set a relaxing tone for the rest of the day or evening. I do find it useful, if something continues to linger in my conscious, to vent a little bit to a loved one but I do not always need a response in return so sometimes just having someone listening to my day is all I need.

This working mindset is related to the uprising of mental health disorders in the United States. It is said that, "Nearly 1 in 5 US adults aged 18 or older (18.3% or 44.7 million people) reported any mental illness in 2016.2 In addition, 71% of adults reported at least one symptom of stress, such as a headache or feeling overwhelmed or anxious." (“Mental Health in the Workplace”, n.d.). Especially for those working in trauma or the criminal justice field, it is so important to practice self care, not only for oneself but for those they work with. Preaching and teaching practices to inmates or trauma patients requires compassion, understanding, self inquiry, and knowing personally what works for you may be useful information that you can tie into your practices.

As previously taught, in Dani Harris and Danielle Rousseau’s “Yoga and Resilience: Understanding Sexual Trauma” trauma resides in the body. Practicing yoga and movement can be greatly beneficial in reconnecting with your body, however, because the "stress response is a biologically derived reaction to a life-threatening event. With trauma, survivors can become stuck in the stress response, reacting even when they are not currently in threat of danger. Survivors may have stress reactions to everyday events and experiences. Further, reenactment and re-experiencing trauma can occur at any point, even during what may seem to be an otherwise ordinary and non-threatening circumstance." As stated before, everyone deals and reacts differently but yoga, mediation, and mindfulness is known to be especially helpful with alleviating stress, anxiety, and other related symptoms, for those who have experienced sexual traumas and leads to significant potential for resilience. This practice is used to "ease the somatic and emotional toll that many survivors pay as a result of their trauma." Additionally found extremely beneficial is deep breathing, which often coincides with the practices done in yoga. Deep breathing quite literally sends signals to your nervous system telling it to calm down.

5 traits of America’s working class - CBS News. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.cbsnews.com/media/5-traits-of-americas-working-class/

Mental Health in the Workplace. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/tools-resources/workplace-health/mental-health/index.html

Harris, D., & Rousseau, D. (2020). Understanding Sexual Trauma. In Yoga and Resilience: Empowering Practices for Survivors of Sexual Trauma. Handspring Publishing.

“The Effects of Untreated Trauma” Live from a Hospital Bed.

Trauma that goes untreated, festers like an undiagnosed infection.

Trauma goes unseen to the naked eye, unlike the common misconception in which mental illnesses are aligned with a physical disability, trauma can appear deep within the societal presentation of "normal". The American Psychological Association defines trauma as an emotional response to a terrible event like a car accident, sexual assault, abuse, or victim to a mass occurrence of violence. Immediately following the initial event, shock and denial are typical. Longer term reactions include unpredictable emotions, flashbacks, strained relationships and even physical symptoms like headaches or nausea. While these feelings are normal, some people have difficulty moving on with their lives.

Untreated trauma can serve as the foundation for excessive amounts of stress throughout an individual's life course. Without proper redirection of how to healthily manage the stress, it effects on the body can result in physical illness. Stress is the automatic response to harmful situations body's, whether they’re real or perceived. In an attempt to prevent injury, a chemical reaction occurs in the body to prevent injury. This reaction is known as "fight-or-flight,” or the stress response. During stress response, your heart rate increases, breathing quickens, muscles tighten, and rise of blood pressure. Despite the body's stress response, there is no immuno-feedback to prevent the effects over time. Stress can affect an individuals emotional stability, behaviors, process functioning, and physical health.

Emotional symptoms of stress include:

- Becoming easily agitated, frustrated, and moody

- Feeling overwhelmed, like you are losing control or need to take control

- Having difficulty relaxing and quieting your mind

- Feeling bad about yourself (low self-esteem), lonely, worthless, and depressed

- Avoiding others

Physical symptoms of stress include:

- Low energy

- Headaches

- Upset stomach, including diarrhea, constipation, and nausea

- Aches, pains, and tense muscles

- Chest pain and rapid heartbeat

- Insomnia

- Frequent colds and infections

- Loss of sexual desire and/or ability

- Nervousness and shaking, ringing in the ear, cold or sweaty hands and feet

- Dry mouth and difficulty swallowing

- Clenched jaw and grinding teeth

Cognitive symptoms of stress include:

- Constant worrying

- Racing thoughts

- Forgetfulness and disorganization

- Inability to focus

- Poor judgment

- Being pessimistic or seeing only the negative side

Behavioral symptoms of stress include:

- Changes in appetite -- either not eating or eating too much

- Procrastinating and avoiding responsibilities

- Increased use of alcohol, drugs, or cigarettes

- Exhibiting more nervous behaviors, such as nail biting, fidgeting, and pacing

Occasional fits of stress are normal for everyone. Working over time, heightened stress due to finals week, or maybe you are giving a public presentation for the first time at your new job. Sweaty palms and a sigh of relief once it's over is a normal recovery response but chronic stress can exacerbate serious health conditions. The prolonged effects of chronic stress can increase the facilitation of many symptoms including; depression and anxiety, cardiovascular disease; heart attacks, abnormal heart rhythm, skin and hair loss; acne, eczema, gastrointestinal problems; GERD, ulcerative colitis, and irritable colon.

Stress is normal, but how you handle it is the tell-tale predictor in ensuring you can effectively reduce or prevent it before the physical repercussions it will enact on your body. Before you are lying in the back of an ambulance, seek professional help if you feel as though your confines of stress have become unmanageable.

Sources

Mayo Clinic. (2021) Symptoms of Stress, Mayo Clinic.

American Psychological Association. (2021)

Delinquency Due to the Foster Care System

This semester we discussed a lot about child development, and risk factors that can lead to psychological problems, and may result in crime activity. I wanted to focus however, on children in the foster care system, and some of the psychological, and behavioral problems that may be developed due to their vulnerable circumstances. It is said that about 70% of people in state prisons have at one point in their life been in the foster care system. Before being placed in the system many children have been in high risk situations such as, “neglect (50%–60%), physical abuse (20%–25%), and sexual abuse (10%–15%; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, U.S. Department of Education, & U.S. Department of Jus- tice, 2000)...Other traumatic exposures that may result in foster care placement are a lack of medical care, poverty, homeless- ness, violence in the home, parental substance abuse, and parental mental illness” (Hornor,pp.160-162). Even while being in the system they may also be at risk for dealing with similar trauma. Children may deal with biological issues such as drug uses, prematurity, obesity, or anemia. These issues may increase if there are multiple children in a household because of the lack of attention.

Due to the high amount of risk in foster homes children seem to struggle in, and outside the home. Children in the foster care system are more susceptible to developing psychiatric disorders that might be long term. These psychiatric disorders may include; depressive disorder, conduct disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), PTSD, antisocial personality, and intermittent explosive disorder. “Travis Hirschi introduced his theory of Social Bonding in his 1969 book ‘Causes of Delinquency.’ His major focus was to contribute to an understanding of the causes of juvenile delinquency. For Hirschi, the ‘bond’ resides in the child and involves four factors or systems: Attachment, Commitment, Involvement, and Belief” (Adoption in Child Time). Without these four stable bonds in a child's life they find it hard to create meaningful relationships,and have good morals, due to lack of attention. Many children thus tend to act out of resentment and form aggressive, or even violent behavior. It is important for Forensic Nurses, CPS workers, or the overall foster care system to make sure they do thorough health evaluations and screenings to find the best possible treatment for these adolescents or young adults. In many cases the most effective treatment plan involves the entire family actively participating in treatment, to help combat some of the issues within the household.

Striking Back in Anger: Delinquency and Crime in Foster Children. Adoption in Child Time. (2019). Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://adoptioninchildtime.org/bondingbook/striking-back-in-anger-delinquency-and-crime-in-foster-children.

Hornor, G. (2014). Children in foster care: What forensic ... - ceconnection. https://nursing.ceconnection.com. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://nursing.ceconnection.com/ovidfiles/01263942-201407000-00008.pdf.

Leading Amongst Corporate Psychopaths

When you hear the word psychopath what do you think of? Most people typically think of some of the more famous serial killers like Ted Bundy or John Wayne Gacy, or maybe a Hollywood depiction like American Psycho or Texas Chainsaw Massacre. But what about the psychopaths that live normal lives amongst the population? They could be your neighbor, your cousin, your coworker or even your significant other. According to the Law Enforcement Bulletin, it is estimated that approximately 1 percent of the general male population are psychopaths alluding that most people already know or will meet a psychopath during their lives (Babiak & O’Toole, 2012). Psychopaths are master manipulators and are skilled in portraying a version of themselves they want their victims to see. This is especially true for a subset of successful psychopaths that Babiak, Neumann, and Hare studied called corporate psychopaths. “Using a sample of 203 corporate professionals from seven companies scattered across the United States, the researchers reviewed records, conducted interviews, and administered the PCL-R, discovering that the prevalence of psychopathic traits was higher than that found in community samples (C & A Bartol, 2021, p. 221).” This research demonstrated what psychologists knew to be true; not all psychopaths commit crime or acts of violence. Hare was famously quoted saying that, “not all psychopaths were in prison, some were in the boardroom (C & A Bartol, 2021, p. 221).”

Since psychopathy is on a continuum and not an identical from person to person, the corporate psychopath may appear differently in each instance. “This personality disorder is a continuous variable, not a classification or distinct category, which means that not all corporate psychopaths exhibit the same behaviors (Babiak & O’Toole, 2012).” Psychopathy is sometimes difficult to identify for even the most skilled law enforcement officer and even psychologists, how is the average citizen going to be expected to recognize this in someone in their lives or their workplace? “According to Drs. Robert Hare and Paul Babiak, corporate executives are about three and a half times more likely to be psychopathic than members of the general public. Positions of power attract a disproportionate number of pathological individuals (not just psychopaths) (Hartley, 2016).”

The concept of corporate psychopaths making their way to the top of businesses has become a common theme in many mainstream media shows and movies. Some that came to mind were The Devil Wears Prada, Office Space, and Horrible Bosses. In each of these movies, it is portrayed in a comical or relatable manner that these highly manipulative and selfish individuals climbed their way to positions of power. Although these movies make light of the situation, this is a very plausible scenario since psychopaths can be highly successful in their professional lives. It is critical that others in leadership positions are able to identify these types of callous and deceptive individuals in order to ensure they do not continue to gain validation or influence.

In my professional career I have almost certainly met individuals that exhibited psychopathic characteristics. As a leader it is your job to protect your team, subordinates, and organization from toxic behavior regardless of how it presents itself. Most psychopaths will initially come off as powerful, smart, charming, and almost too good to be true. An experienced leader may be able to see through the façade, but most people will likely be under their spell initially. Although many of their skills like boldness, quick wit, and charm may initially impress those in a workplace, immediate supervisors, peers, and subordinates will likely see through the mask a psychopath is wearing. Therefore, as a leader it is critical to consider how subordinate and peers view others in your organization.

Sources:

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2021). Criminal behavior: a psychological approach (12th ed.). Pearson.

Paul Babiak, PhD., and Mary O’Toole, PhD. (2012). Law Enforcement Bulletin: The Corporate Psychopath, https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/the-corporate-psychopath

Dale Hartley, MBA, PhD. (2016), Psychology Today: 5 Ways of the Corporate Psychopath, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/machiavellians-gulling-the-rubes/201609/5-ways-the-corporate-psychopath

Preventing School Shootings: How Do We Keep Kids Safe at School?

Preventing School Shootings: How Do We Keep Kids Safe at School?

In today's world, parents fear sending their children to school. In the middle of algebra classes, and band rehearsals, students must practice lockdown drills in case a shooter ever enters their school. This is not something any parent wants to imagine. So, how do we keep kids safe? How do we prevent another Columbine, or Sandy Hook, or Oxford from happening?

As of September 2020, the Center for Homeland Defense and Security found that there had been 68 school shootings since Columbine in 1999 (Melgar 2020). School shootings in the United States happen an average of once every 77 days. This number is show to be increasing over the years (Melgar 2020). Having 68 school shootings in eleven years is such a high number, and to have that number growing is startling. From 1999 to 2014, the average number of days between shootings was 124 days. From 2015 to 2018, the average was 77 days (Melgar 2020). That’s a drastic change. The idea of school shootings becoming even more frequent should be upsetting for everyone.

The Everytown for Gun Safety fund has created a plan to help keep children safe at school, and to stop school shootings from being a normal occurrence. The plan lists eight targets to stop gun attacks in schools. The targets are: 1. Pass Extreme Risk Laws 2. Encourage Secure Firearm Storage 3. Raise the Age to Purchase Semi Automatic Firearms 4. Require Background Checks on All Firearm Sales 5. Create Threat Assessments in Schools 6. Put in School Security Upgrades 7. Create Trauma-Informed Emergency Planning 8. Create Safe and Equitable Schools (Everytown Research & Policy 2021).

While Everytown’s plan is thorough, and hits many key points, it would be extremely hard to pass. The United States is so polarized that passing gun laws or any legislation to prevent school shootings will face a lot of backlash. Because of this, I think Everytown’s plan will be viewed as too extreme. We have so many school shootings in the United States, but school shootings have become a political issue, and that makes it nearly impossible to do anything to stop them. Schools can work on promoting mental health awareness, they can do research-baked risk assessments, and can do more to prevent bullying. This certainly won’t prevent all school shootings, but it could be away to stop the number of school shootings from increasing.

Sources:

Everytown Research & Policy (2021). In Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. Retrieved from https://everytownresearch.org/report/preventing-gun-violence-in-american-schools/

Melgar, L. (2020, September 17). ARE SCHOOL SHOOTINGS BECOMING MORE FREQUENT? WE RAN THE NUMBERS. In Center for Homeland Defense and Security. Retrieved from https://www.chds.us/ssdb/are-school-shootings-becoming-more-frequent-we-ran-the-numbers/

In Search of the Successful Psychopath

What is a successful psychopath?

To study a successful psychopath, we must identify what it is to succeed as a psychopath. In a sense, the psychopath that behaves in whatever way they choose and is never caught has succeeded. That behavior may be the classic serial killer but, recognizing that psychopaths may not always be set apart from society, it may also be embezzlement, fraud, identity theft, or just being a nasty coworker. But the goal of studying the successful psychopath is to explore the phenomenon of psychopaths who succeed within the boundaries of normative culture, not those whose transgressions go unnoticed. Further, as Welsh and Lenzenweger observed, defining the successful psychopath as the one who is never apprehended fails to consider the perspective of the individual in question, defining them by their relationship to criminal justice rather than their own experience (2021). What about classic metrics of success in a capitalist society - income, acclaim, and power?

Moving past psychopathy as a monolith

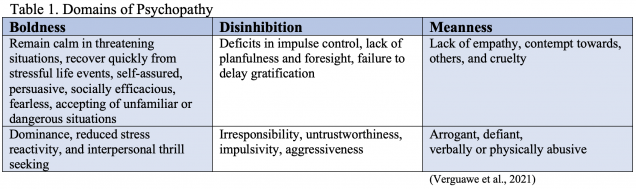

While scores to such as PCL-R can be used to determine the presence and degree of psychopathy - useful for formulating an approach to treatment - the individual components of those scores may become lost once the label is applied. But to facilitate the exploration of an anomaly such as the successful psychopath, researchers have adopted the triarchic approach, allowing characterization of in terms of boldness, meanness, and disinhibition (Table 1) rather than only a total score. In particular, the domain of "boldness" has been hypothesized to be a fulcrum around which the successful psychopath may pivot from the Hollywood serial killer to the hero of the boardroom.

Bold Belgian bosses

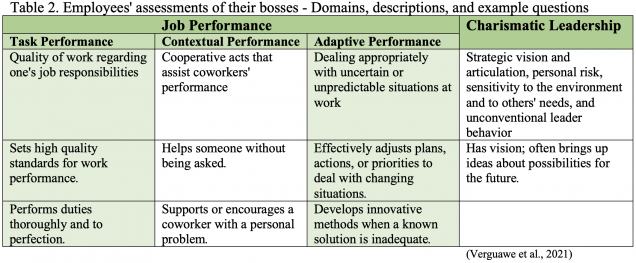

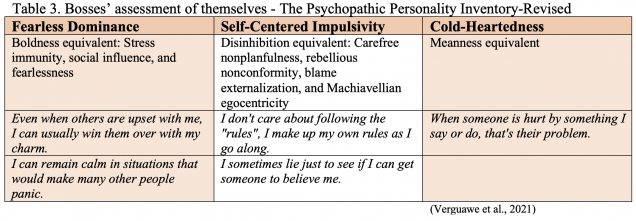

Vergauwe, Hofmans, Wille, Decuyper, and De Fruyt recruited psychology students to evaluate their bosses' effectiveness as leaders (Table 2), and recruited those bosses to complete the Dutch version of the psychopath exam: The Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised (Table 3). This study was performed twice, to assess for reproducibility, the second with a much larger sample size.

Vergauwe et al. offered three hypotheses. The Differential Severity model suggested a curvilinear relationship between psychopathic characteristics and business success. Psychopathy would increase success until a point of diminishing returns, at which point higher scores would lead to worse performance. This hypothesis did not examine the relationship between specific domains of psychopathy, rather it interpreted the total score. The results from the first and second studies refuted this, showing a linear relationship rather than curvilinear.

The Moderated Expression model added an additional criterion: Conscientiousness, as measured by the self-reported Dutch NEO Five-Factor Inventory (eg. I have a clear set of goals and work toward then in an orderly fashion). It posited that characteristics of psychopaths that might otherwise be maladaptive could be tempered and even made beneficial in the presence of certain qualities (others are noted below). This theory bore fruit in Study #1, showing that Task Performance worsened in individuals with low Conscientiousness as Self-Centered Impulsivity increased. In the presence of high Conscientiousness, Task Performance improved as Self-Centered Impulsivity went up. However, Study #2 did not replicate this result, and the presence of Conscientiousness actually correlated with a steeper drop in Contextual Performance and Charismatic Leadership as Cold-Heartedness increased. Of note, other research has suggested that qualities such as Executive Functioning, Intelligence, or even good parenting techniques may provide the moderating effects that turn increasing psychopathic domain scores into success (Welsh & Lezenwegere, 2021).

It was the Differential Configuration model that provided Vergauwe et al. with the most reproducible results. This hypothesis proposed that increases in certain domains of psychopathy would lead to greater success while increases in others would lead to worsening dysfunction. This was the hypothesis that assumed the least covariance between domains - an increase in boldness need not be accompanied by an increase in disinhibition or meanness, and a lower score in one might not portend lower scores in another. In Differential Configuration, Boldness (Fearless Dominance, in the Dutch model) showed positive, linear relationships with effectiveness, statistically significant in the arenas of Adaptive Performance and Charismatic Leadership. In contrast, Disinhibition was significantly associated with decreasing Task Performance, and Meanness was negatively associated with all leadership qualities. It seems Boldness may be the difference between the successful and unsuccessful psychopath, at least in the business world.

Successful psychopath in the streets - and in the sheets?

Boldness may have cemented its value in the work of Pilch, Lipka, and Gnielczyk when they looked at the role of psychopathic traits and social status as they related to romantic and sexual relationships (2021). In contrast to the other studies, their work left the evaluation of psychopathic characteristics to another individual, not the one being assessed for psychopathy. In further contrast, the research focused on women, a largely neglected population in the world of psychopathy research. The individuals in question were still men, and the study was limited by a heteronormative structure, but it provided women the opportunity to assess their partners’ psychopathic qualities, which were then analyzed in terms of self-reported satisfaction with both romantic and sexual relationships. Boldness won the day once more, identified as the quality most likely to increase women’s satisfaction rather than damage it. Increasing Meanness and Disinhibition scores had a deleterious effect.

What makes a successful psychopath is not yet well-characterized. Even the definition of a successful psychopath is unclear. But research to this point has suggested that Boldness, associated with resilience and social efficacy, may be the key to what makes one psychopath a secretive, perhaps murderous societal aberration, and another the leader of a Fortune 500 company - or perhaps the president of the United States.

Pilch, I., Lipka, J., & Gnielczyk, J. (2022). When your beloved is a psychopath. Psychopathic traits and social status of men and women’s relationship and sexual satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 184, 111175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111175

Vergauwe, J., Hofmans, J., Wille, B., Decuyper, M., & de Fruyt, F. (2021). Psychopathy and leadership effectiveness: Conceptualizing and testing three models of successful psychopathy. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101536

Welsh, E. C. O., & Lenzenweger, M. F. (2021). Psychopathy, charisma, and success: A moderation modeling approach to successful psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 95, 104146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104146

Trigger Warnings: Necessary or Trivial?

Throughout the past almost two years of the pandemic, mental health awareness has become extremely widespread through the use of social media and due to the depressing nature of the pandemic. In online communities, individuals are making large strives towards being politically correct, enhancing emotional intelligence, and attempting to be sensitive to others, specifically through what are known as “trigger warnings”. Previously, I had only ever seen them used as joke or “meme” material, but with the increasing awareness of mental health, I realized that I should properly educate myself. So what exactly are trigger warnings? Why are they used?

Trigger warnings are warnings that “flag material that might cause distress or discomfort, or possibly trigger a panic attack in students with post-traumatic stress disorder” (3). Originally used online for topics that primarily included sexual assault, the term has now been coined for use with topics that include race, sexual orientation, disability, colonialism, torture, and other intense subjects (1). In classroom settings, students are encouraged to speak up about triggering topics, but do they even help with preventing stress responses?

On one end of the spectrum, trigger warnings can be seen as keeping others’ best interests in mind, and on the other end, it can be seen as something that does not “give them the freedom to develop their antifragility.” (1). For some students, this might be the case, as some trigger warnings have been shown to increase anxiety and stress responses as opposed to not including one. The most effective treatment for individuals with PTSD is a cognitive behavioral therapy that is trauma-focused. One of the main components of trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy is called exposure therapy, where the individual is exposed to the traumatic event in some capacity to help the individual cope with their trauma and desensitize them to the traumatic event (4). The avoidance of these potentially triggering topics actually can make the stress response worse when the individual is exposed to it and can make intrusive thoughts about the trauma worse (1).

The true nature of trigger warnings, however, is that they are not supposed to prevent students from developing their antifragility by avoidance, but rather strengthen and fine-tune it, with warnings that say to regulate their emotions more with this unpleasant topic that is about to be discussed (1). The adverse of those intended effects have been shown in individuals who are not able to emotionally regulate their stress responses well. In a study in 2019 led by Mevagh Sanson, it was found that individuals who received a trigger warning before reading triggering material had no reduction in stress response compared to those who did not receive a trigger warning before reading the material (2).

While trigger warnings seem to be considerate and emotionally aware, they could be doing more harm than good for those who struggle with PTSD. Even though not every individual is the same and has the same experience, letting people figure out their triggers, and how to handle them is essential to healing from trauma. Putting censors on every potentially triggering topic is not going to expedite that.

Citations:

1. Kaufman, S. B. (2019, April 5). Are trigger warnings actually helpful? Scientific American Blog Network.

2. Mevagh Sanson, D. S. (n.d.). Trigger warnings are trivially helpful at reducing negative affect, intrusive thoughts, and avoidance. SAGE Journals.

3. NCAC report: What's all this about trigger warnings? National Coalition Against Censorship. (2020, January 2).

4. PTSD Facts & Treatment: Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA. PTSD Facts & Treatment | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA. (n.d.). Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/treatment-facts.