“Network maps of public social media discussion in services like Twitter can provide insights into the role social media plays in our society”, according to Smith, Rainie, Himelboim and Shneiderman (2014). This idea of network maps is directly related to infomediation, which is defined as “the set of socio-technical mechanisms such as software, services, and infrastructures that provide internet users with all types of information online and connect them with other users.” (Smyrnaios, 2018). A few things are important to note about this definition — online users implying that there is some type of mediation or internet-related aspect and that different information connects these online users, through these mechanisms.

Smith et al. (2014) looked at aerial views of Twitter conversation networks to define six conversational archetypes. Masterchef Junior and Sephora and some examples of how networks can vary.

Masterchef Junior

In this graph (https://nodexlgraphgallery.org/Pages/Graph.aspx?graphID=11438), we can see how the nodes or vertices are situated on the outside and that there are numerous edges that are moving inwards and connecting the nodes. From Smith et al. (2014), the Masterchef Junior graph would be defined as a broadcast network that is in-hub and spoke because it portrays many spokes or edges pointing inward to a hub. It is also a star-shaped graph as there isn’t much interaction between the members of the network. This graph features a network of 521 Twitter users over a 2-hour 14 minute period from Friday 8th November, 2013 at 19:03 UTC till 8th November, 2013 at 21:18 UTC. The graph is a directed graph because it shows the connection between users in the form of mentioning a user and replying to a user — @GordonRamsay and @MasterChefJuniorFox. Each edge represents a ‘reply’ or mention. However, the graph is also part indirected in nature because it also looks at the hashtag #MasterChefJunior. From the network structure, one can see that the edges stemming from Gordon Ramsay are thicker thus implying stronger connections. We can say that tagging Gordon Ramsay and the Masterchef Junior pages on Twitter were some of the key terms that connected users on Twitter.

It would make sense that users are using these key terms because they want to feel connected to the contestants and host (Gordon Ramsay) of the show. If I wanted to tweet my opinion about that 8th November, 2013 episode, I would mention the name of the television show itself, the team I was supporting, and maybe reply to Gordon Ramsay’s tweets about the episode. If everyone who watched the episode and who supported specific contestants replied and mentioned these terms, a small cluster would be created just how there is a blue network for “Team Dara” in G2. My replies and mentions would then be the affordances of the Twitter network and if I used #MasterChefJunior along with my tweet, then my hashtagged phrase would also be an affordance of the network that is being engaged.

The Masterchef Junior graph is a perfect example of how a network serves as a “place to connect with community” (Rainie & Wellman, 2012, p. 218). When I tweet and mention the contestants, I am becoming part of the Masterchef community and am part of a shared-interest community, which in this case is food, children cooking, and Gordon Ramsay. This purpose of networks builds on the idea that people with shared interests may start out as strangers, but can end up as friends which is an important aspect of building relationships with other people. The result of these broadcast networks that are in-hub and spoke is set of communities within a larger Masterchef Junior community.

Sephora

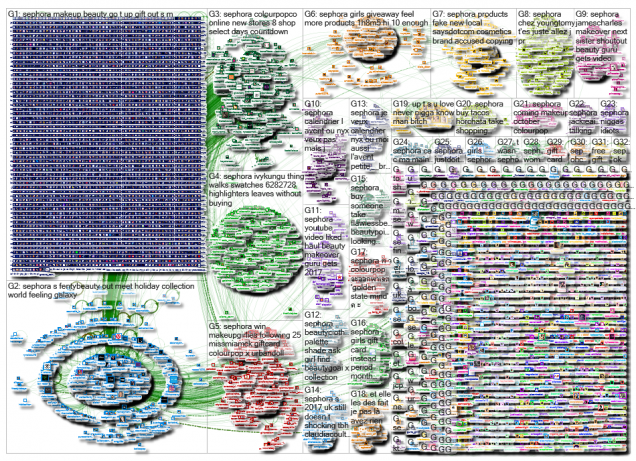

In the above graph that depicts Sephora as a brand (https://nodexlgraphgallery.org/Pages/Graph.aspx?graphID=127176), we can see that there are multiple solid clusters where all its users are talking about Sephora in one way or another. This graph would be defined as a fragmented brand cluster network that has multiple small groups. It features a network of 16,853 Twitter users that contains tweets over a 2-day 30 minute period from Sunday, 22nd October 2017 at 3:37 UTC till Tuesday, October 24th, 2017 at 22:07 UTC. Sephora represents a directed graph because it includes any tweet replies which contain the word ‘Sephora’ in it. In this diagram, the replies and mentions of @Sephora would be the affordances that are engaged. In G2, there is a small community of individuals who mentioned Sephora in reference to their Fenty holiday collection and in G14, there is a community of different individuals in the UK. But together, all these fragmented clusters form a brand cluster network. Even though people globally are replying to and mentioning Sephora, there is mass interest but little connectivity. If I tweet how great Sephora’s birthday specials are in Boston and so does another user in Colombia, it does not mean that we are “connected” per se — there is just a general big interest in Sephora birthday specials.

As Rainie and Wellman mention, stories in social media may have different pathways to capture the attention of their audience. (p. 214). Even though, I don’t know the person in Colombia, I may value their opinion because Sephora’s birthday specials are interesting to me. Someone else in India may also be interested in Sephora and thus a fragmented cluster is formed.

From the two different types of network graphs of Twitter users for Masterchef Junior and Sephora, it is clear that people can be connected in a variety of ways and that infomediation occurs globally and through people and the internet. I think it is interesting how everything comes back to the people who are actually using social media and how they interact with brands on a daily basis. Just from analyzing graphs and identifying Twitter networks, we can learn so much about brands and their users, and be a part of the infomediation community.

References:

Rainie, H., & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The new social operating system. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Smith, M. A., Himelboim, I., Rainie, L., & Shneiderman, B. (2014). The Structures of Twitter Crowds and Conversations. Transparency in Social Media, 67-108.

Smyrnaios, N. (2018). Internet Oligopoly: The corporate takeover of our digital world. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.