The rise of social networking sites, the Internet, and mobile computing have ushered in a new era of social organization and interaction. This three-pronged change, dubbed the Triple Revolution by Rainie and Wellman (2012), has “made possible the new social operating system… call[ed] ‘networked individualism’” (p. 12). The characteristic features of this transformative event enable people to act more as “connected individuals and less as embedded group members” (p. 12). Today, instead of existing solely in the corporeal confines of local communities, people are able to harness a vast virtual web of informational and communicative networks with seemingly limitless potential. These networks, supported by the affordances of social media and Internet platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Google, create opportunities to seek and gather knowledge and communicate effortlessly. But at what cost? The seemingly omnipotent power of Internet platforms undergirds a fundamental discrepancy between their users and operators. The purpose of this essay is to expose some of these tensions, to illustrate the power of online communication through network analysis, and offer a critique of the present state of the Triple Revolution.

A Web of Communication

The datafication of our online activities provides new opportunities for analyzing these interactions. Social network analysis is one field of research that provides a set of conceptual frameworks and quantitative skills for illuminating the seemingly nebulous nature of online lives (Rosen & Barnett, 2016). Social media platforms frequently become objects of study, with researchers focused on sundry topics like the strength of relationships between users, the nature of the content shared, the discursive characteristics of online language, and more. Politics and political communication is one specific discipline receiving much attention in this regard. In one illustrative study, Smith et al. (2014) explored Twitter conversation around political issues. They identified and described six conversational structures: divided, unified, fragmented, clustered, and inward and outward hub structures (p. 2). As the authors note, “these are created as individuals choose whom to reply to or mention in their Twitter messages and the structures tell a story about the nature of the conversation” (p. 2). Following is an explication of two graphics with respect to network structure.

Network 1: Beto

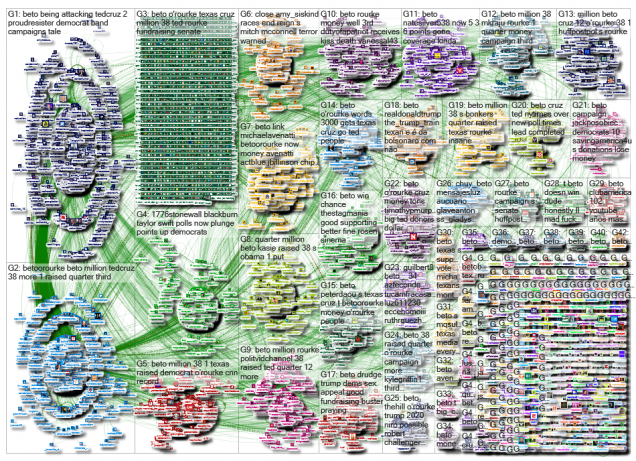

Keeping with the political theme of Smith et al. (2018), the following is a NodeXL graph of a “network of 16,629 Twitter users whose recent tweets contained ‘Beto’, or who were replied to or motioned in those tweets…” (NodeXL, 2018). Beto refers to the Democratic candidate for Senator in Texas, Beto O’Rourke. NodeXL is a free, open-source network analysis and visualization software addon for Microsoft Excel that “enables network overview, discovery, and exploration” (Smith et al., 2014, p. 11).

Applying the work of Smith et al. (2014) offers some clarity to the deluge of text and colors in the graph. The graph of Beto tweets is defined by community clusters, in which “popular topics may develop multiple smaller groups, which often form around a few hubs, each with its own audience, influencers, and sources of information” (p. 4). The edges in the Beto graph depict strong activity between two main groups (1 and 2) and decreasing density between the main groups and others. The top Twitter profiles tagged in this conversation were Senator Ted Cruz (@tedcruz), Beto O’Rouke (@betoorourke), an anonymous user with 184,000 followers (@1776Stonewall), and President Donald Trump (@realdonaldtrump). The hashtags #beto, #txsen, #betofortexas, and #vetobeto were the most prevalent. The number one link shared by users in this graph was to a Dallas News story about Beto O’Rourke raising $38 million during his campaign.

The platform affordances of twitter are evident in this graph. As a microblogging site Twitter affords the opportunity to communicate with other users. Tagging other people by using @ and entering their username, as well as utilizing hashtags, facilitates these interactions. The 2018 Senate race in Texas is particularly contentious. Tapping into the power of social media has enabled politicians to expand their constituencies and connect with their communities. Supporters of both Senator Cruz and Beto O’Rourke also wield the power of networked individualism to empower themselves. As Rainie and Wellman (2012) note, “networked creators have… felt empowered not just by the support they received from other networked individuals, but also by the influence they gained through creation” (p. 219). This assertion is directly supported by the position of the user @1776Stonewall as a top user within the Beto network.

Network 2: KamalaHarris

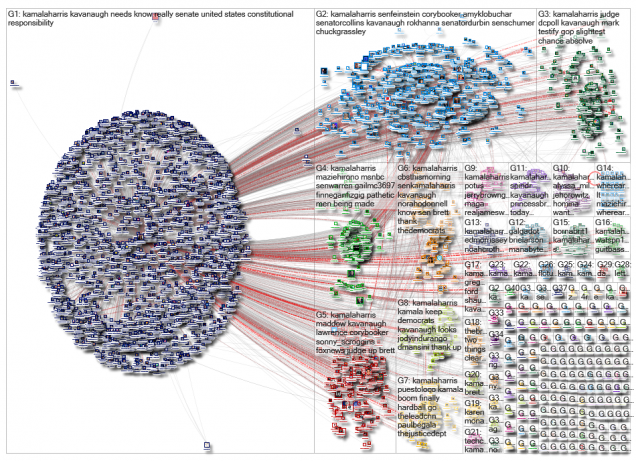

This second NodeXL graph (below) is also political in nature, and “represents a network of 4,828 Twitter users whose tweets… contained ‘KamalaHarris’ or who were replied to or mentioned in those tweets (NodeXL, 2018a). Influential users in this network were identified as Senator Kamala Harris (@kamalaharris), Senator Diane Feinstein (@senfeinstein), an anonymous user, @PuestoLoco, and another user, @KLowgren. The top hashtags in this collection of tweets were #kamalaharris, #kavanaugh, #wherearekamalaharrisdocuments, and #metoo.

The structure of this network is best described as a broadcast network, or one in which the structure “is dominated by a hub and spoke structure, with the hub often being a media outlet or prominent social media figure, surrounded by spokes of people who repeat the message generated” by them (Smith et al., 2014, p. 42). The original tweet, posted by Senator Harris, described a lawsuit she had filed on behalf of the American people to force the nominating committee to release White House documents related to Judge Kavanaugh’s tenure as an assistant to the president (Harris, 2018).

The nomination of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh was extremely controversial, and the debate over his elevation to the court played out fiercely in the American mainstream media and online social networks. Additionally, opponents and supporters of Kavanaugh leveraged their online networks and resources to create rallies on the ground. Although these rallies were fundamentally different in scope and nature from the Tahrir Square protest in 2011 was described by Rainie and Wellman (2012), they exhibited analogous traits with respect to digital tactics used, the movement from cyberspace to physical space, and the creation of sense of shared purpose (p. 208). As the authors describe, “As in almost all social movements … [revolutions] are built upon established networks of friends and political groups…” (p. 210).

Platform Power and Big Tech

The ability for social networks to engender change and bolster political movements raises some questions about the role platforms play in the process. As Bucher and Helmond (2016) incisively point out, “while affordance theory has mainly put emphasis on the question of what technology affords users, the socio-technical nature of social media platforms also begs the reverse question of what users afford platforms?” This inquiry is parallel to the political economic critique espoused by Smyrnaios (2018). Conceiving each platform as an infomediary, or “an information broker who acts as a mediator between sources of information and clients or users,” Symrnaios underscores the oversized role that platforms have in shaping the form and function of discourse across their products (p. 1508). The political conversation taking place in the Beto and KamalaHarris networks are, in fact, both monitored and monetized. As each player in the oligopolistic market seeks to achieve its financial goals, and expands its influence and capacities through vertical integration, there are increasingly few places left that meet the Internet’s original promise as a realm for the free exchange of ideas, self-expression, and communication without the presence of corporate profiteering.

Works Cited

Bucher, T. & Helmond, A. (2018). The affordances of social media platforms. In J. Burgess A. Marwick & T. Poell The sage handbook of social media (pp. 233-253). 55 City Road, London: SAGE Publications Ltd doi: 10.4135/9781473984066.n14

KamalaHarris. (2018, September 18). Republicans have refused to release Kavanaugh’s White House documents that are relevant to the confirmation process. As a last resort, we’re suing to get them for the American people. [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/KamalaHarris/status/1042161346719174656

Node XL. (2018). Node XL Graph Gallery: Beto. Retrieved from https://nodexlgraphgallery.org/Pages/InteractiveGraph.aspx?graphID=171189

Node XL. (2018a). Node XL Graph Gallery: KamalaHarris. Retrieved from https://nodexlgraphgallery.org/Pages/Graph.aspx?graphID=168364

Rainie, L., & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The new social operating system. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Rosen, D., & Barnett, G. (2016). Introduction to the Network Analysis of Digital and Social Media Minitrack. System Sciences (HICSS), 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on, 2027.

Smith, M. A., Rainie, L., Himelboim, I., & Shneiderman, B. (2014). Mapping Twitter Topic Networks: From Polarized Crowds to Community Clusters (Rep.). Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center.

Smyrnaios, N. (2018). Internet Oligopoly: The Corporate Takeover of our Digital World. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Publishing.