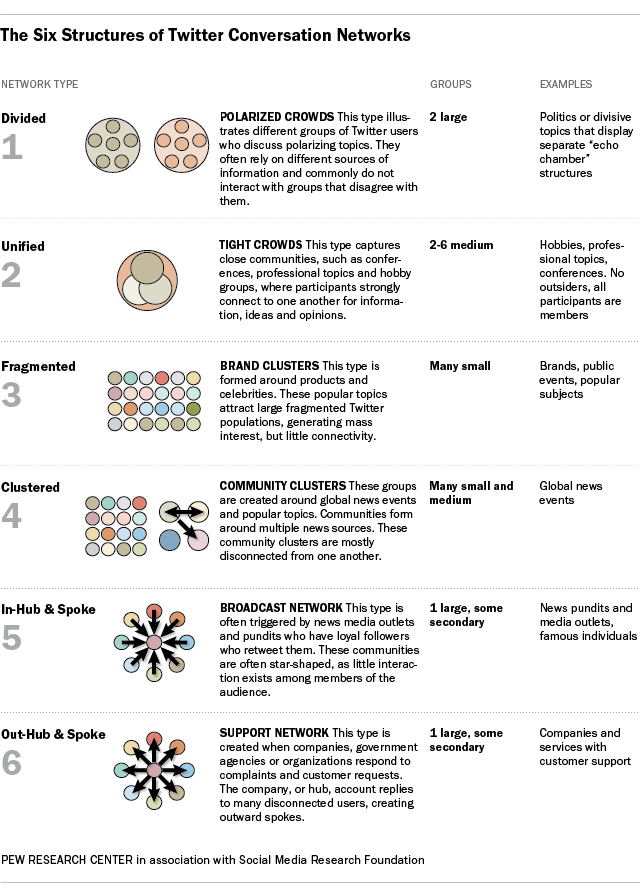

“Making is connecting,” put by sociologist David Gauntlett under the discussion of how media-making in the network operating system as a participatory act (Rainie & Wellman, 2012). A report posted by the Pew Research Center on 2014 provided an aerial photograph of the social media activity, here emphasizes Twitter, showing a rough size and composition of the population. The quantitative and qualitative study of the conversations conducted on Twitter was done by Smith et al., where they identified six different social media network structures as the archetypes. With the help of NodeXL, Smith et al. analyzed thousands of social media network maps on various subjects and then observed the six patterns that can no longer be reduced to one another. Each of them has a distinguishable social structure and shape: divided, unified, fragmented, clustered, and inward and outward hub and spokes (Fig. 1).

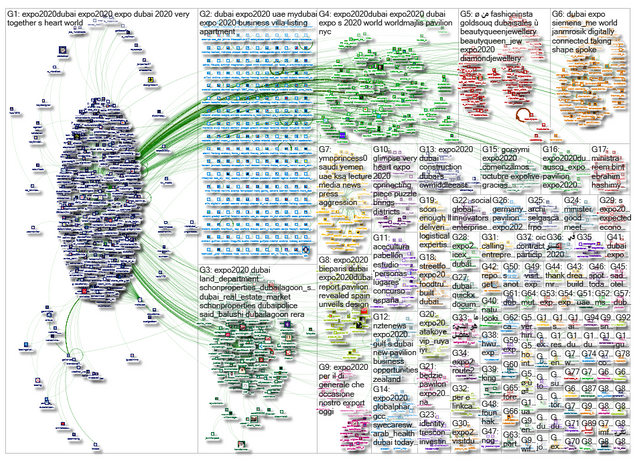

Since social media never follow a specific trajectory with its innate randomicity, those structures always appear in a hybrid manner. For instance, a network graph of 1902 Twitter users whose tweets contented “#expo2020” collected between September 4 to October 11, 2018, by NodeXL has a more complex structure (Fig. 2). There are green lines, the “edges” to indicate the relationship between users. This network map presents in a hybrid structure of Brand Clusters as well as an inward hub and spokes (the Broadcast Network). The Broadcast Network features a hub where other discussion centered around, such as news and media outlets. The largest “#expo2020” group at the left of the graph (G1) is surrounded by a large number of participants who connect to a center node, which is the Expo2020Dubai official account. The cluster of G1 linked by “edges” to Group 3-6, some isolated but densely interconnected groups of interconnected people interested in discussing related topics, in such scenario, of real estate market (Group 3), pavilion construction (Group 4), fashion industry (Group 5), etc.

It is worth noting that commentary from many disconnected participants shown in the form of Brand Clusters also exists in the graph. In Group 2, a significant number of disconnected people tweet the topic of business and apartment listing with the hashtag of “#expo2020.” Certainly, the properties posted are not related, there are limited interaction and overlap regarding the content and shared resources. By actively choosing which topic to follow and actively participate, users claim the power of self-expression.

The graph mentioned above is comparable to the example that the Library of Congress was asking people to add labels to the historic photographs that put by Rainie and Wellman. During the process, network individuals provided their interpretation through tags, taking the power of providing information about the artifacts from professional historians. Those ‘amateur expertise’ made the collaborative creation as a form of self-empowerment, where a community of contributing and learning are formed. Sociologist Ronald Breiger calls “duality of persons and groups” when talking about the phenomenon that people link groups, and groups also link people (Rainie & Wellman, 2012).

Another network graph of 17,919 Twitter users who tweets contained “MentalHealthAwarenessDay” was drawn from October 10 to October 11 over the 3-hour, 2-minute period (Fig. 3). This model accord with the Community Clusters structure that listed by Smith et al. In Group 1, community clusters have large numbers of users who adopted the hashtag on October 10, while the discussion may or may not relevant to the topic, and they do not link to one another. At the same time, the national day ignited multiple conversations online. The network graph shows interconnected groups were having a conversation by cultivating own audience and community: how mental health matters to people (Group 2); personal perspective/reflection on mental illness (Group 3); organizations to looking for help (Group 4). Numbers of subgroups have made a diversified conversation. People were looking at the mental health issue by thinking of other helpful resorts: healthy foods, companionship from pets, spiritual comfort, self-distraction, etc.

Though mainstream media outlets led some of the discussion, individuals’ engagement was still prominent. Nike Smyrnaios questioned that nowadays the oligopoly is trying to control the interpersonal communication and content dissemination over digital media by asserting the power over services, software, and infrastructure. They build the pipes and have control over infomediation. Smyrnaios also argue that the decision-making oligopolies have vertically integrated the infomediation infrastructure. Hence, the development of social media platforms is asymmetrical since users, organizations, and firms are in competitive markets whereas the oligopolistic players marking the rules.

Rainie and Wellman indeed discussed how the boundaries between producers and consumers are blurred with the fast-growing infomediation in the age of the Triple Revolution. More junk information was produced, which put by Erving Goffman as “interaction pollution” in 1974 (Beniger J.R., 1987). The struggle of mass communicators to achieve interpersonal effects is somehow similar to the situation that people are holding various opinions trying to claim his superiority over the other. However, the point being made here still focuses on the reshuffled relationship between experts and amateurs and how they exert influence in the world (Rainie & Wellman). Though the socio-technical mechanism constructed by the oligopolies claimed the power of “platformisation,” knowledge is always crowdsourced and generated by people.

To conclude, modern interpretation of mass society, cultural studies and of oppressions suggest the consumer is a passive cow, milked by large corporations (Katz, 2006). However, the research of Smith et al. indicates that spontaneous interaction conducted by social network users are leading the formation of the infrastructure of the community, instead of passively drifting with the tide, which is also supported by Rainie and Wellman’s literature. Users now are more than mere consumers. They took advantage of what has been provided there to make public discourse and reflect personal as well as communities’ taste to the outside world.

Citation:

Rainie, H., & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The new social operating system. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Smith, M. A., Rainie, L., Shneiderman, B., & Himelboim, I. (2014, February 21). Mapping Twitter Topic Networks: From Polarized Crowds to Community Clusters | Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/02/20/mapping-twitter-topic-networks-from-polarized-crowds-to-community-clusters/

Smyrnaios, N. (2018). The Privatisation of the Internet. In Internet Oligopoly: The Corporate Takeover of Our Digital World. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Beniger, J. R. (1987). Personalization of mass media and the growth of pseudo-community. Communication Research, 14(2), 352-371.

Katz, J.E. (2006). “Chapter 4: Public performance of mobile telecommunication” in Magic in the Air: Mobile Communication and the Transformation of Social Life. (pp.51-64). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.