The continuous growth in the amount of Facebook users may suggest one thing: people love to build online social networks and tend to make their network sizes as big as possible. Though some people may have up to 500 Facebook friends, as Dunbar suggested, people’s personal networks actually have a maximum size of 150. According to him, the network size is decided by people’s “social brain” — the cognitive information-processing capacity. Dunbar’s number was challenged by many researchers after, among them Boissevain found the real average size of the network to be more than 600 (Rainie & Wellman, 2012). The network size has always been a popular research subject and some recent studies suggest there is a close relationship between network size and human brain structure. The research conducted by Kanai et al. proved that the number of social contacts on a web-based social networking site is strongly associated with the structure of focal regions of the human brain. In addition, because memory is critical for the maintenance of a large number of social ties, memory capacity is another important constraint on the network size (Kanai et al, 2011).

The limit on network size results in people having different levels of social ties. As Dunbar pointed out, there are four layers of relationships, and the outer most layer is consisted of people who are just nodding acquaintances (Rainie & Wellman, 2012). Some other researchers divided social ties into primary groups and secondary groups. The primary group is small in size, intimate and enduring; group members include family members, relatives and friends. Primary group members are also referred to as “significant others” as they are emotionally tied to individuals and tend to be influential in their lives (Sullivan, 1953). The secondary group is larger, and the interactions are guided by rules or regulations and hence more formal. Secondary group members are usually from work or various organizations, and the membership may range from short to extended in duration (Thoits, 2011). In fact, the distinction between primary and secondary group is similar to the differentiation between strong and weak ties suggested by Rainie and Wellman.

There is a Chinese saying that “More friends, more roads.” It means if you have more friends, you will get more solutions when faced with difficulty. I think the saying accords with the idea that the larger the network, the more ties that can pass along information. The network size is important in many ways, but I am particularly interested in how network size can influence mental well-being.

When Rainie and Wellman made the connection between network size and health benefits, they mentioned the term social support. Social support refers to the social resources that persons perceive to be available or that are actually provided to them by nonprofessionals in the context of both formal support groups and informal helping relationships (Gottlieb & Bergen, 2009). Social support can also be understood as functions performed by significant others or secondary group members (Thoits, 2011). Common types of social support include emotional, instrumental, and informational support (Gottlieb & Bergen, 2009). Simply put, emotional support is showing love, care and sympathy or giving encouragement. Informational support is providing people with facts or advice to help solve their problems. Instrumental support includes offering behavioral and material assistance with practical tasks or problems (Thoits, 2011). People get social support from their social ties to other people, and the closer the relationship is, the wider the range of types of support can be generated. According to Gottlieb and Bergen, social support is not a commodity that resides in the provider and passes to the recipient, but that it is an expression of the mutuality and affection characteristic of the relationship between the parties (Gottlieb & Bergen, 2009).

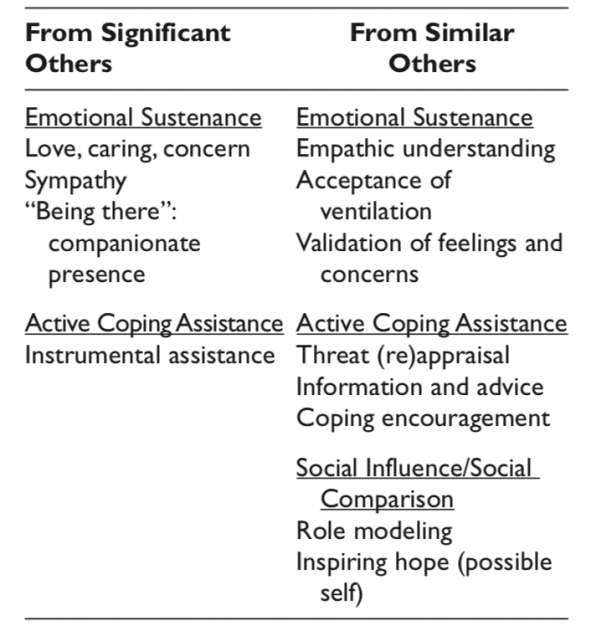

Barrera pointed out that the size and cohesiveness of a person’s social network and the types of relationships in a network influence the receipt of various kinds of social support (Barrera, 1986). His point just reinforces the idea raised by Rainie and Wellman that a larger network size will provide more social support. But how does social support influences people’s mental well-being? Thoits provided an explanation focusing on 2 types of supportive behaviors – emotional sustenance and active coping assistance. Coping assistance, according to Thoits, means supporters advise or implement problem-focused or emotion-focused coping strategies that they would use themselves when faced with the same stressor (Thoits, 2011). He also further classified the effects of 2 types of supportive behaviors by 2 groups of social ties that I mentioned before – Primary group (Significant others) and Secondary group (Similar others).

Specifically, emotional sustenance provided by primary group members include expressing their understanding of the stressor for the individual and listening to his/her reactions, worries and tentative plans. Hopefully, their caring and comforting will reduce the psychological distress and harmful physiological arousal. The active coping assistance offered by significant others has various forms, including instrumental aid, information and advice, and coping encouragement. Similarly, members from secondary group also provide emotional sustenance and active coping assistance through offering direct experiential knowledge. Because secondary group members’ social roles are usually similar to those of the stressful individuals, the social similarity will boost the utility of the experience-based support they provide. In addition, secondary group members can also provide a third kind of support – a social influence as they serve as role models who can be observed and emulated. Social influence helps to shape the individual’s coping efforts, reducing situational demands and emotional reactions directly and indirectly augmenting his or her sense of control over life (Thoits, 2011).

Refrences

Barrera, Manuel, Jr. 1986. Distinctions between Social Support Concepts, Measures, and Models. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 413–45.

Cohen, S., & Janicki-Deverts, D. (2009). Can We Improve Our Physical Health by Altering Our Social Networks? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(4), 375-378.

Gottlieb, & Bergen. (2010). Social support concepts and measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(5), 511-520.

Kanai, Bahrami, Roylance, & Rees. (2012). Online social network size is reflected in human brain structure. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 279(1732), 1327-1334.

Rainie, Lee., Wellman, Barry. (2012). Networked: The New Social Operating System. The MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Thoits, P. (2011). Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145-161.