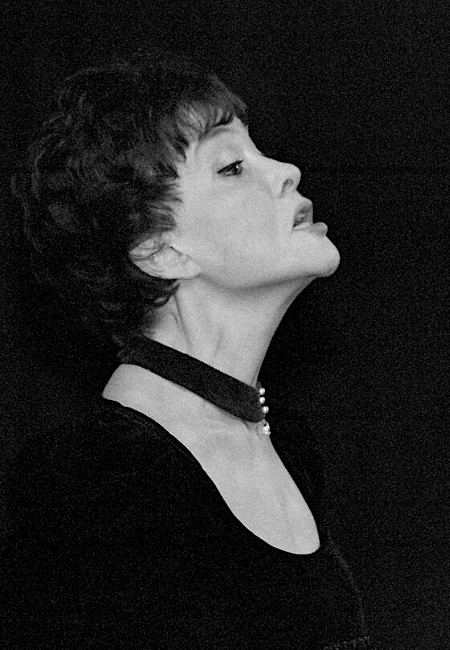

Biography Bella Akhmadulina

Bella (Izabella) Akhatovna Akhmadulina (1937 – 2010) is the Russian poet, short story writer and translator. She was born and brought up in Moscow in the family of a Tatar father who was a deputy minister and a Russian-Italian mother. Her first published verses appeared in 1955 in Moscow’s October journal when she was a student of the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute. She married the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko in 1954 and divorced him in 1960. That same year she graduated from the Literature Institute and took a trip throughout Central Asia. This journey motivated her to write about her “Asiatic blood,” a recurring theme in Fever, and Other New Poems (1968). Then she was married to the writer Yuri Nagibin, before marrying the artist Boris Messerer in 1974.

In 1962, her first collection of poetry, The Harp String, received much acclaim. In her finest poems Fever and Tale of the Rain, Akhmadulina conveys her belief that creativity has a liberating effect on individuals yet leads to scorn and alienation from the crowd. She embraced Western ideology and showed widespread sympathy for the dissident movement throughout the 1960s and 1970s although she was not active in it. She took part in the cult poetic evenings at the Polytechnic Museum and concerts at the Luzhniki Stadium where Bella Akhmadulina with three other famous poets, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Andrei Voznesensky, and Robert Rozhdestvensky recited her lyrics for thousands of spectators. However, unlike Yevtushenko, who can be called a “citizen poet,” Akhmadulina always remained a lyrical poet. Critics called her poems apolitical as in her writing she describes things like rain, articles in an antique store, aspirin, a car.

Under the rule of Leonid Brezhnev, she was barred from the Writer’s Union and banned from publication. Akhmadulina’s work in general wasn’t widely published at the time, even though her public readings drew enthusiastic crowds. When she was banned from the Soviet Press and media, she became a noted translator of poems, especially from Georgian, and delivered her statements through the foreign press and radio. In the late 70s she was a participant in the first non-censored Soviet literary almanac, The Metropol.

New themes and images emerge in Akhmadulina’s poems, notably in the collections The Secret (1983) and The Garden (1987). Some of the most exciting experiments in her poetry involve sense of humor and an audacious way with images. Her long poems involve dreamlike, symbol-laden events, which often go to historical memory expressed in dense, allusive language enriched by coined words and archaisms. In his introduction to The Garden, translator, F.D.Reeve says “Critics have called her poetry classical, pointing out its use of rhyme, meter, and standard prosodic pattern. In the course of thirty years, however, her poetry has changed, expanding its themes and ranging its diction from archaic to slang. At the same time, the idea of classicism has evolved. .. Born one hundred years after Pushkin’s death, Akhmadulina has cloaked her spirit with his …” (Reeve 1990:4).

As she matured, her writing became more philosophical, even religious. Although generally avoiding social issues, her late poetry largely deals with the themes of sickness, insomnia, and suffering over her inability to write in an atmosphere of muteness, shadows, and darkness. In the early 2000s, with a series of very personal poems she explores intimate themes from her alienation from socially defined normalcy to illness and the sense of approaching death.

Sources

Reeve, F.D. Introduction. The Garden: New and Selected Poetry and Prose. Translated by F.D.Reeve. Henry Holt & Co. 1990.

Sonia, I. Ketchian. The Poetic Craft of Bella Akhmadulina. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

Глоток тепла средь ледяного мира…»: био-библиогр. путеводитель к юбилею Б. Ахмадуллиной /сост. Е.Е. Цупрова; Самарская ОЮБ. – Самара, 2017.