Importance of Trauma-Informed Interventions

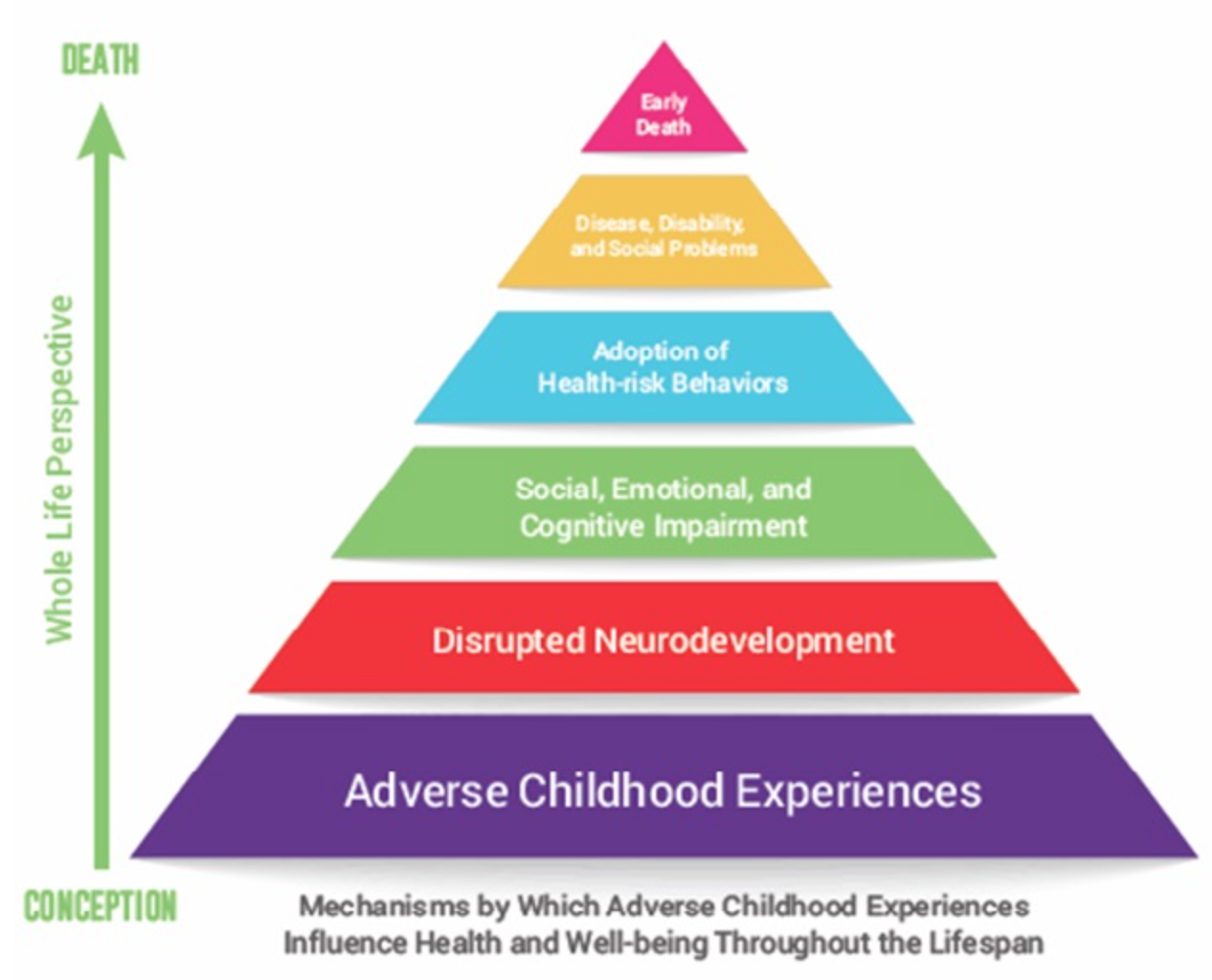

Studies have proven that severe mental health problems are more closely related to emotional abuse than physical abuse because emotional abuse is often times not taken as seriously because of its relative “invisibility” in comparison to physical abuse, resulting in delay in recognition and action (Rees 2009). This is reflected in the low political priority in developing prevention and intervention programs for emotional abuse, and the lack of funds allocated for resources and training (Rees 2009). In this way, the inadequate methods for providing children with resources to cope with emotional abuse, are seen to contribute to its longevity and permanency in affecting the lives of at least a quarter of American children. The most important aspect of treatment for children that have experienced emotional abuse is its timely start, because of the magnitude of long term effects of trauma that can develop. In The Body Keeps Score Bessel van der Kolk (2014) proposes that “child abuse’s overall costs exceed those of cancer or heart disease” and that “eradicating child abuse in America would reduce the overall rate of depression by more than half, alcoholism by two-thirds, and suicide, IV drug use, and domestic violence by three quarters” (pg. 150). As the number of ACEs increases so does an individual’s overall healthcare utilization, which makes federally funded insurance policies and private insurance policies more expensive to maintain, eventually resulting in increased tax rates for all (Felitti, & Anda, 1998). In addition, when early intervention techniques are facilitated it leads to an overall healthier environment that encourages positive relationships in society.

Psychological maltreatment is considered a form of abuse on its own but it also often stems from other forms of maltreatment such as neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. When children grow up in a home where their parents are aggressive or incompetent, the psychological abuse that they experience puts them at risk for a myriad of consequences as they mature. There is a strong correlation between the frequency, severity, and proximity of the trauma and the health risk behavior and disease risk in later adulthood. One of the largest conclusive studies about child abuse and neglect and later life health and wellbeing was conducted in Southern California in 1995. This investigation measured the amount of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in participants lives. The scores that participants got in three categories: abuse, household challenges, and neglect, represents their cumulative childhood stress. As the number of ACEs goes up so does the risk for substance abuse, depression, heart disease, financial stress, risk for intimate partner violence, risk for sexual violence, poor academic achievement, and many more health related difficulties (Felitti & Anda, 1998). Data collected from this study shows that almost two thirds of participants reported at least one ACE and more than one in five reported three or more ACEs. This shows that although it is fairly common for children to have adverse experiences growing up, their long term effect is determined by the child’s supports and resiliency (Felitti & Anda, 1998).

When a child experiences a traumatic event the overstimulation of their autonomic nervous system can trigger permanent changes in the development of their neural pathways and cause chronic dysregulation of their endocrine systems which alters the epigenetic profile of their DNA. Further, the repeated activation of the hypothalamic- pituitary- adrenal axis (HPA axis) decreases neurogenesis, and therefore decreases the brain’s neuroplasticity, or ability to repair itself (Kiyimba, 2016). The repeated activation of the HPA brought on by childhood stress also elicits pro-inflammatory tendencies which result in the etiology of many chronic diseases. When the stress occurs at such a crucial point in development, the childhood, it begins to dictate how certain body systems develop, notably the immune cells of the body. By allowing children to experience traumatic stress so young and not providing prevention efforts, the government is in effect perpetuating this cycle of abuse twofold, since it becomes engrained in their genes and will be passed down through generations in their DNA and in the way they parent their future children (Kiyimba, 2016).

Trauma- Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) combines many theoretical approaches, including family systems, development theory, attachment theory, and client- centered therapy as a means of support for children after experiencing trauma and has been proven as the strongest evidence based treatment (Timmer & Urquiza, 2014). TF- CBT is structured, short- term, components based treatment which involves the child and their non-offending caregivers, this form of therapy is thought to relive some of the negative impact of the emotional abuse, as well as improve parenting skills, parental support, and decrease parental distress. Including non offending caregivers in this therapy has its foundation in attachment theory, since parents have such a large influence in providing support and a safe environment for their child, it is important that they are included in the healing process. TF- CBT’s main goal is to provide the child with the appropriate skills and cognitive processes to begin to live a productive life after experiencing trauma (Toth & Manly, 2011).

Following a traumatic event, children develop negative associations for things they experience at the time of the trauma, so they are often afraid when they think of the abuse, so they avoid thinking about it. While this may seem effective at the time, prolonged avoidance of the trauma will make its emotional impact even larger (Reece & Hanson, 2014). Through TF-CBT a therapist can gradually expose children to reminders of the trauma they experience so they can slowly disassemble how they are feeling and cope with the trauma without being re-traumatized. There is strong support for this model of therapy and as more research is done it can be modified to provide further benefits for children and families affected by emotional abuse.

Overall, the most effective forms of intervention are the ones that involved a variety of professionals all working together to help the child. A therapist would be the first step to uncover the depth of the trauma and recommend further treatment. A psychiatrist or pediatrician could prescribe medications if behaviors are severe enough. Social workers can help the family move forward and access appropriate support (Timmer & Urquiza, 2014). Having many different professionals working together as a team allows comprehensive treatment for the child, in hopes to rehabilitate them in all aspects of their lives. When pediatric primary care physicians are able to develop professional and meaningful relationships with the parents of their patients they are able to gain greater insight to the etiology of their health conditions and provide resources and support when necessary.

Community based prevention programs are becoming more widespread as politicians and educators are realizing that children who have experienced emotional abuse, or are currently experiencing it, require support and guidance from all spheres of their life. Communities That Care (CTC) is a prevention program designed to be implemented in the community to reduce mental, emotional, and behavioral problems that result from any challenges that children may face in their childhood (Salazar et al., 2014). This program identifies risk factors for each individual child such as family conflict, early behavioral problems, and delinquency. By identifying these factors as early as possible, it is likely to decrease the long- term effects of emotional abuse. In order to make this program as effective as possible, it was designed with a high level of collaboration with the child welfare system and other leaders in the community where it is implemented. Studies have shown that prevention programs based in the community tend to have the most positive effect because of the high degree of support. Before Communities That Care can be implemented more widely more trials need to be performed to assure its effectiveness and the proper training of leaders (Salazar et al., 2014).

References

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D, et. al (1998). Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many Leading Causes of Death in Adulthood. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 14(4), 245-258. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

Kiyimba, N. (2016). Developmental trauma and the role of epigenetics. Healthcare Counseling & Psychotherapy Journal, 16(4), 18-21.

Reece, R. M., & Hanson, R. F. (Eds.). (2014). Treatment of Child Abuse: Common Ground for Mental Health, Medical, and Legal Practitioners (2nd Edition). Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

Rees, C. (2009). Understanding Emotional Abuse. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 95(1) 59-67. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

Salazar A, Haggerty K, Lansing M, et al (2014). Using communities that care for community child maltreatment prevention. American Journal Of Orthopsychiatry, 86(2):144-155. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

Sterling, J., & Amaya- Jackson, L. (2008). Understanding Behavioral and Emotional Consequences of child abuse. Pediatrics, 122, 3rd ser., 667-673. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

Timmer, S., & Urquiza, A. J. (2014). Evidence-based approaches for the treatment of maltreated children: Considering core components and treatment effectiveness. Dordrecht, NY: Springer. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

Toth, S. L., & Manly, J. T. (2011). Bridging research and practice: Challenges and successes in implementing evidence- based preventative intervention strategies for child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 35(8), 633-636. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

Van der Kolk, B., (2014). What’s love got to do with it? In The body keeps score: the brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma (pp. 139-170). New York City, NY: Penguin Books.