South Africa (Spring 2019)

Student participants in the Social Impact Field Seminar 2019 South Africa share their reflections on their learning experience in the below blog posts (unedited)

Importance of wildlife and conservation for sustainable economic development

By Luke

Reflecting back on our trip to South Africa, I am encouraged about the recent developments in the country and the importance they seem to be placing on sustainability and the way the recognize their wildlife as one of the most important resources that the country has.

As someone who cares deeply about land and wildlife conservation, I have struggled with the idea that as countries develop and prosper, often that is at the expense of the environment, wildlife, and conservation land. Reflecting back on our trip to South Africa, I am encouraged about the recent developments in the country and the importance they seem to be placing on sustainability and the way the recognize their wildlife as one of the most important resources that the country has. In our visit with NEPAD, they really cared about having a sustainable solution in the long term, not one that would boost the economy at the expense of the environment. When we asked them to prioritize the creation of jobs and cleaning the environment in the upper Olifants River basin, they said they care more about the environment and putting in place a truly sustainable industry. When we floated the idea to them that they could develop tourism in the area centered around their wildlife, that was a real option for them and something they were excited about. The idea that conservation and the creation of wildlife reserves is maybe more beneficial for a region than the establishment of a traditional industry was something very encouraging to me.

Our experience at the Cheetah breeding center raised a lot of questions in my mind around the purpose of such a place. You think of cheetahs and wild dogs as being so rare and endangered, yet here they are with close to a hundred of each, waiting for the right opportunity to send them out to a reserve. Because of the large range of wild dog packs and both the inbreeding and large range of cheetahs, there isn’t enough room in the current reserves for more of them. The solution for cheetahs and wild dogs is not to establish breeding programs, it is to protect more land so animals at places like the cheetah center can send their animals to a place with enough space for more cheetahs and wild dogs. Through our conversations with NEPAD, it sounds like South Africa is on the right track and in the right mindset to prosper economically while also bringing along its wildlife in that prosperity. Even things like Eaton Electric’s microgrids could lead to more conserved land as electricity could enable the establishment of reserve in the most rural areas. Industries other than farming could pop up in those areas once reliable electricity is present, freeing up land for other uses. I hope to journey back to South Africa in the future and see the progression along the path this country has set up for itself.

Social Impact convert!

By Madeline

Seeing new cultures, particularly ones where there are growth opportunities, ignites an energy for change and hope in the world. Upon my return, I decided to register for the Social Impact program, knowing now this was a track that I needed in my future career. Truly a unique experience, this trip was one that I will treasure and a special part of my graduate education.

In my Uber to my Capetown hotel, I remember thinking about the stark contrast between this mountainous, ocean facing city and the urban landscape of Johannesburg that I had just come from. Being in this new environment immediately put me at ease, the ocean was the same one that was in Boston, and the working harbor was reminiscent of the Boston seaport. I felt that I had to keep reminding myself that I was, in fact, in Africa. The hiking, beach time, penguins, and sightseeing was all other worldly. This whirlwind version of Capetown, led by my trusty Uber driver for the weekend, swept me off my feet. Only to come planted back down by these intense reminders of South Africa’s past, poverty, and growth that is still to be done. Reminders like children begging for money and food outside of the braai we went to in one of the townships. Reminders like load shedding. Reminders like the roadside venders, happy to just sell a few ears of corn.

When going back through my pictures, one really stuck out to me. I snapped a picture of something that I thought in the moment would be memorable as a school in the middle of mountains. Upon further review, the billboard in the picture is far more memorable. It shows a drawing of eyes and says “don’t look away” and on the otherside “report hate”. This reminded me of the eyes of Dr. TJ Eckleburg, something I had to ask Google to assist with remembering the name of. This was a theme from The Great Gatsby (throwback to 7th grade literature class). In Great Gatsby, there were a pair of eye glasses above the valley and seemed to be watching over everyone as the story unfolds. It symbolized God looking down and judging human society as a “moral wasteland”. Whether intentionally similar to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s work or not, I was grateful to catch this nod to that same symbol and a tragic history.

I also felt very fortunate to be able to get to know a few people while in South Africa and openly discuss issues going on in their country not specific to the city, but to the country. One of these was one of my sister’s friends from her time abroad there. He opened my eyes to the burgeoning start up industry in the city of Capetown, that he is currently working in. He brought me to areas that are being gentrified and reminded me of areas that I had seen in the United States. He was originally from Sandton in Johannesburg, but had come to Capetown for school. He loves Trevor Noah and he loves Johannesburg. He is proud to be from South Africa despite the deeply dark and recent history against his race. This is a theme that I noticed in both Capetown and Johannesburg. There didn’t seem to be harbored animosity or resentment, but hope for the future. I’m not sure if it’s certainty that where they are coming from was horrific enough that they must move forward, or momentum, but something is propelling South Africa onward. With this hope, also comes concern; the rampant corruption faced in the government recently, creates skepticism and worry in the mind of many South Africans.

Before I left for the trip, I was slightly apprehensive to go. My friend reassured me that “because you’re a Sagittarius, you might be nervous, but need this”. I came back a full astrology believer; she was right. Seeing new cultures, particularly ones where there are growth opportunities, ignites an energy for change and hope in the world. Upon my return, I decided to register for the Social Impact program, knowing now this was a track that I needed in my future career. Truly a unique experience, this trip was one that I will treasure and a special part of my graduate education.

Drawing parallels

By Kara

[M]y most significant takeaway, which I wasn’t really expecting, is a drive to do something about this issue I care deeply about. I have spent recent years reading countless fiction and nonfiction writing about all things race in America. But especially now, I know I need to DO more. Put my knowledge into action.

When talking to friends and family about the trip, what I wanted to say was how much fun I had, how much I learned from the companies I visited, and how much I was inspired to bring this knowledge into my own career. However, I kept feeling like I’d be doing an injustice if I skipped over talk of the impact that the country’s racial divide had on my perception of South Africa. It’s something I have been grappling with since I’ve returned. How does a country truly move on from a history so defined by its racial tensions? Maybe what I am struggling with most is that, as difficult as it was to see the lack of progress in South Africa, I couldn’t stop thinking about how much it reminded me of what still must be done to address the massive disparities in the U.S. today.

A lot of my peers wrote about the impact of the words we heard all week long: “freedom to choose.” I understood this phrase to be an attempt at justifying how an overwhelming majority of black South Africans remain living in the overcrowded and under resourced townships. It was such an evident falsehood, and I can’t help but draw further comparisons to systematic racism in the U.S. Here, 45.8 percent of young black children (under age 6) live in poverty, compared to 14.5 percent of white children (The State of Working America). I can imagine that many white Americans could claim that this is the black parents’ sort of “freedom of choice”. The truth, of course, is that our system was created to, and continues to, work against black people. People of color face structural barriers in all different aspects of life: housing, healthcare, employment, and education (The Urban Institute). They are unfairly targeted by police, makeup over 60 percent of people in prison, and face longer sentences and harsher punishments than their white counterparts (Center for American Progress). It’s not surprising, seeing how American policing literally began with the development of slave patrols, which helped wealthy (white) landowners find and punish black people (whom white people considered to be their property) (Police Studies Online). Given today’s notably high rates of arrests, assaults, and killings of black people by officers in the U.S., we see how history dating back well over 100 years ago still resonates today. Therefore, I find the claim that the housing situation in South Africa is a reflection of “freedom of choice”, and not a direct result of the horrific system of apartheid, to be shockingly ignorant and counterproductive to progress.

Instead of making these claims to make white South Africans feel better, it is time to take real action. My hope for South Africa is that its leaders will allow for discussion to address these systematic disparities, so this enormous divide can diminish. Nelson Mandela was impactful in leading the way with this kind of work, and in order to uphold his vision, there must continue to be representation of black leaders, and real support for all black South Africans.

From this journey, it is true that I have learned a lot about what kind of work I want to do with my career, and how many different ways business can make a sustainable impact. However, my most significant takeaway, which I wasn’t really expecting, is a drive to do something about this issue I care deeply about. I have spent recent years reading countless fiction and nonfiction writing about all things race in America. But especially now, I know I need to DO more. Put my knowledge into action. I hope to continue to learn from others and get involved in as many ways as I possibly can.

In the words of Nelson Mandela, “To be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains”

By Stephanie

In the words of Nelson Mandela, “To be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

I arrived home to Boston almost two weeks ago from our field seminar in South Africa. Our final spring quarter at Questrom has started and it is easy to get immersed into the busy schedule and routine of classes again. But I have tried to make a concerted effort to take the time to really reflect on my experiences in South Africa – whether that’s going through the many pictures I took or sharing stories with friends and family. I have had a lot of people ask about how the trip was and the first things that people tend to ask are “How beautiful was Cape Town?” and “How amazing was the safari experience?” While these were certainly fun moments of the trip, they do not come close to summarizing my full learning experience and the takeaways I left with. I have struggled with how to describe the experiences we encountered with poverty, wealth disparities, and perpetuated racism and give these topics the full justice they deserve. Ultimately, I think it is something that people need to experience personally in order to truly understand the complicated present-day South Africa, but sharing some pictures has helped me start this conversation with friends and family.

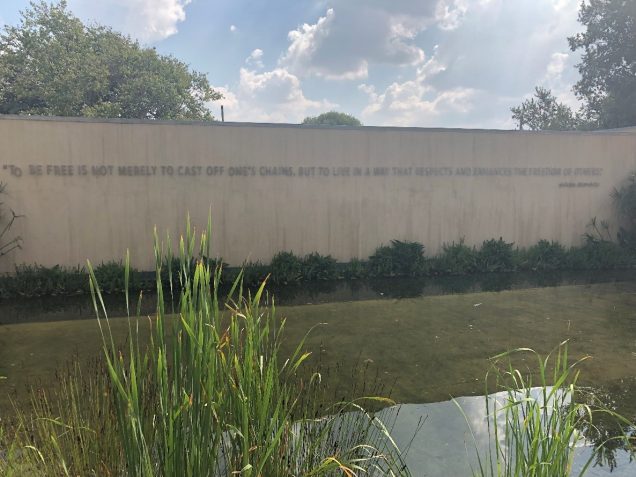

One picture that I took that has stood out to me (although a bit blurry) is of a large quote displayed outside of the Apartheid Museum. It is a quote from Nelson Mandela and it says “To be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

I think this quote encapsulates the vision Nelson Mandela had for South Africa and is also a conversation-starter for the work that still needs to be done today. While yes, there are no longer physical chains in South Africa (in terms of the institutionalized racism during the Apartheid period), perpetuated wealth and race disparities, along with continued intentional and unintentional racism, inhibit large parts of the population of South Africa from living up to their full potential.

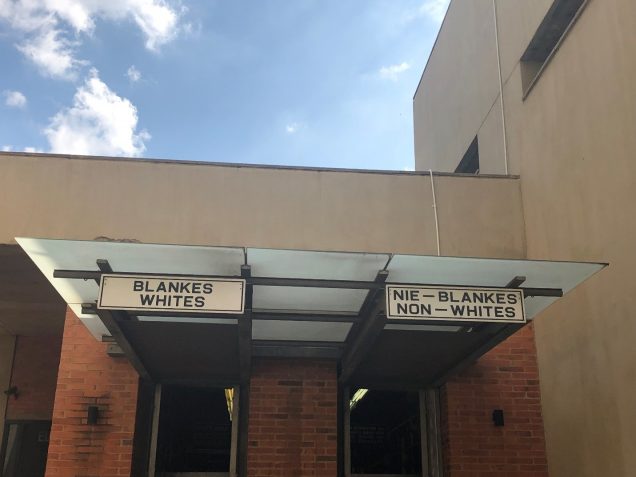

Taken at the Apartheid Museum. Representation of formal segregation seen during Apartheid.

Looking back at some pictures I took of neighborhoods such as Soweto, it is hard to buy the idea of “freedom of choice”, which we were repeatedly told on our tour is the feeling in South Africa today. I find it hard to believe that the majority of the people in these neighborhoods “choose” this life for themselves – rather it is the conditions and disparities of the current society that have chosen for them.

Neighborhood of Soweto, outside of Johannesburg

According to a survey conducted by the South Africa Institute for Race Relations, 60% of South Africans do believe that race relations have improved since 1994. While this number does sound promising it is important to also note that 16% believe things have stayed the same and an alarming 21% believe things have become worse. This makes me wonder…what portions of the population are reporting that things are better vs. worse and are there disparities here? Do impoverished black communities truly believe in “freedom of choice” today, or is this instilled by the same affluent white communities that look very much the same today as they did during Apartheid?

While reflecting on this situation is disheartening, I think it is very important that we were exposed to these sides of South Africa. Others who travel there on vacations may only experience the “Cape Town” and “Safari” sides of South Africa, but this does not tell the whole story. And for any improvements to prosper, both South Africans and stakeholders need to have these conversations and not hide behind fabricated falsehoods that everything is okay. On a promising note, we did visit one company during our seminar that is tackling these exact issues head on. Mandate Molefi is a consulting firm that works with leaders of businesses, organizations, and schools to drive culture change and build inclusive environments with the vision “to heal and free people to be their best” (which is very reminiscent of Mandela’s vision). The consulting firm works to dispel the intentional and unintentional biases that leaders perpetuate surrounding issues of race, sex, LGBTQ, and other aspects of diversity. I was so impressed by the work this company is undertaking and the tangible skills it is equipping leaders of today with in order to change mindsets and ultimately organizational/community cultures.

To me, this is what South Africa needs more of today. Companies and leaders like Mandate Molefi who are not afraid to acknowledge the stark realities of the landscape in South Africa and to work towards equipping all people with the conditions and environments they need to be truly free. Believing that everything is healed will not help anything – change will only result if these tough conversations are confronted head on.

Power outages and changing plans

By Laura

While our seminar in South Africa has left me with many insights on the outstanding impact that so many organizations are having – on diversity and inclusion, public health, job creation, and more – the story I keep returning to is what it felt like to realize I’d begun strategizing my life around power outages, and wondering at what point I would start saving for my own solar panels.

Since returning from South Africa, I keep thinking back to the few days after the seminar that I spent in Cape Town. I rented an Airbnb with three other classmates in Camps Bay, a seaside town near the base of Table Mountain. On our second night in the house, we lost power starting at 8:00 PM. After discovering our lighter was out of fluid and using the gas stove to light our candles – I’m still pretty proud of that – we settled in for what we hoped was a brief delay to our evening plans. For the first hour we assumed the lights would come back on at any minute. After the second hour, we grumbled about the inconvenience. We found a board game to play and chatted about classes for Mod 4. Without power we had no Wi-Fi, and without Wi-Fi we couldn’t call an Uber to get into downtown. Finally at 10:30 PM the power returned and we were able to reassess our plans.

Though we had studied the effects of load shedding – power outages due to the power utility Eskom’s lack of capacity to meet demand for electricity – we hadn’t experienced it directly while we were in Johannesburg. Sometimes traffic lights without power caused traffic issues, as our guide could attest to when she got caught in a jam for over two hours on her way to meet us one morning. However, we were staying in a hotel with backup generators, so we didn’t directly see the impact when other parts of the city lost power.

On our third afternoon in Cape Town, the power went out again at noon. We had already arranged for transportation for day’s activities, so the inconvenience was minimal. We learned that Eskom planned another blackout that evening at 8:00 PM. It happened while we were out for dinner, and we watched as some businesses came back online with backup generators while others relied on emergency lighting. When we returned to our house, we quickly set about lighting candles again to ride out the last hour of the outage.

We listened to the radio during our car rides when we were in Cape Town. Nearly every station touched on the load shedding, which had reached Stage 4. At this stage, Eskom sheds 4000 megawatts of the national load. The company tries to control where the outages occur to avoid a complete blackout. During our visit, part of the capacity issues came after the massive cyclone in Mozambique damaged the country’s power exports to South Africa. Radio DJs mused that the May elections might bring some change, while the guide on our wine tour blamed people who connected to the power grid without paying. The origins of Eskom’s issues are wide-ranging, and the proposed solutions come with their own challenges. The people in South Africa have seen significant price increases in the past several years, and since March 16 the power outages have increased significantly as well.

By our last day in Cape Town, we had begun strategizing around the predicted outages. We planned to leave the Airbnb with plenty of time before the likely outage at noon. We arranged to meet up at the waterfront because it was a major landmark that any taxi driver would know, so we wouldn’t need to worry about directions if we couldn’t hail an Uber. After spending the day exploring, we made sure to go out to dinner at a restaurant that we’d seen keep the lights on during the earlier outage so we could be certain that we’d have Wi-Fi to call our Uber to the airport.

What struck me the most was how quickly we began structuring our plans around the outages, and how difficult it was to be caught unprepared. For us, it was an inconvenience at most. It delayed our plans and left us without our typical leisure activities. But during a workday or an evening at home, it’s more than an inconvenience. My teachers didn’t use PowerPoints when I was in high school, but we still needed to have the lights on to see the board properly. Especially as more educational material involves digital content, teachers need power in their classrooms. I’m not entirely certain what I would have done all day in my last job without power; even our meeting agendas were in Google Drive. All of my cooking equipment is electric. Reading a book by candlelight sounds romantic until my eyes begin to tire.

Though I intellectually recognized the impact that access to power can have, actually experiencing load shedding in Cape Town emphasized its importance. While our seminar in South Africa has left me with many insights on the outstanding impact that so many organizations are having – on diversity and inclusion, public health, job creation, and more – the story I keep returning to is what it felt like to realize I’d begun strategizing my life around power outages, and wondering at what point I would start saving for my own solar panels. If I started thinking about that after four days, what does that mean for South Africa’s citizens, especially those who can’t afford to make investments in private infrastructure?

Experiencing load shedding reinforced to me the potential for impact in South Africa. One benefit of consistent access to power – apart from knowing that your medicines will be stored at the correct temperature, your computer will start up when you need to work, or your stove will cook your dinner – is the time saved not thinking about how to operate without electricity. I hope to that the South African government, Eskom, and whatever public-private partnerships develop in the coming years can give that time and certainty back to South Africa’s citizens.